(Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistacritica #artcritcinterview #ericaromano

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Erica, quando, come e perché hai iniziato ad occuparti d’arte?

Erica Romano: Ciao, “il quando” si perde in un tempo indecifrabile, fluttuante, incerto e forse incosciente. “Il come” e “il perché” credo ne siano un’inevitabile conseguenza, ma animati entrambi da un forte desiderio di conoscenza, spinta dalla curiosità di esplorare l’intelligenza creativa umana in tutte le sue espressioni. Tento di rispondere, allora, riportando due eventi apparentemente lontani tra loro: il primo uno stage universitario che avevo fortemente voluto presso l’Ufficio Esportazione della Soprintendenza di Firenze, perché interessata a vedere da vicino il “dietro le quinte” di come si spostano, si maneggiano e viaggiano quelle opere d’arte tanto amate che ritenevo “intoccabili”; il secondo, invece, l’esigenza di virare direzione rispetto all’idea di sentirmi una pedina nelle mani di quei macchinosi ingranaggi della vita accademica. E così, mentre stavo per laurearmi alla facoltà di Storia dell’Arte sui lungarni pisani, iniziai a frequentare associazioni e circoli culturali tra Prato e Firenze, perché avevo voglia ed esigenza di incontrare, condividere riflessioni e avere un rapporto più concreto e ravvicinato, tangibile, con protagonisti e realtà diverse che agivano all’interno del panorama artistico contemporaneo, esplorando contesti, incontrando operatori, artisti e pubblici. Iniziavo a capire che “occuparsi d’arte” significava “occuparsi di persone”.

Pd’A: Chi erano le persone che frequentavi?

ER: Frequentavo soprattutto artisti anche già affermati e a cui devo davvero molto, perché mi hanno trasmesso parte della loro ricca esperienza, condividendo la loro visione del mondo attraverso la loro arte. Ho poi iniziato a spingermi anche altrove, verso altre piazze come Milano e Roma, o altri lidi come la Svizzera, dove ho potuto incontrare nuovi stimoli e modalità operative, conoscendo organizzazioni più o meno strutturate, spazi indipendenti, riviste di settore e giovani artisti la cui ricerca ruotava intorno alla compenetrazione tra musica elettronica, performance, danza e fotografia. Un ruolo importante lo ha avuto, infine, la frequentazione di alcune associazioni per quanto riguarda il valore della partecipazione e della messa in comune di idee e interessi da finalizzare in attività culturali, un percorso che ha portato oggi a scegliere di collaborare stabilmente con alcune di queste associazioni per la progettazione didattica e curatoriale. Dovrei poter tracciare il profilo di tanti volti, ma credo che nella vita di ognuno esista una lunga galleria di ritratti, più o meno amati e conosciuti, che hanno contribuito in modo diverso alla definizione della propria identità professionale e non solo.

Pd’A: Nella babele linguistica dell’arte contemporanea c’è qualcosa che ti attira maggiormente?

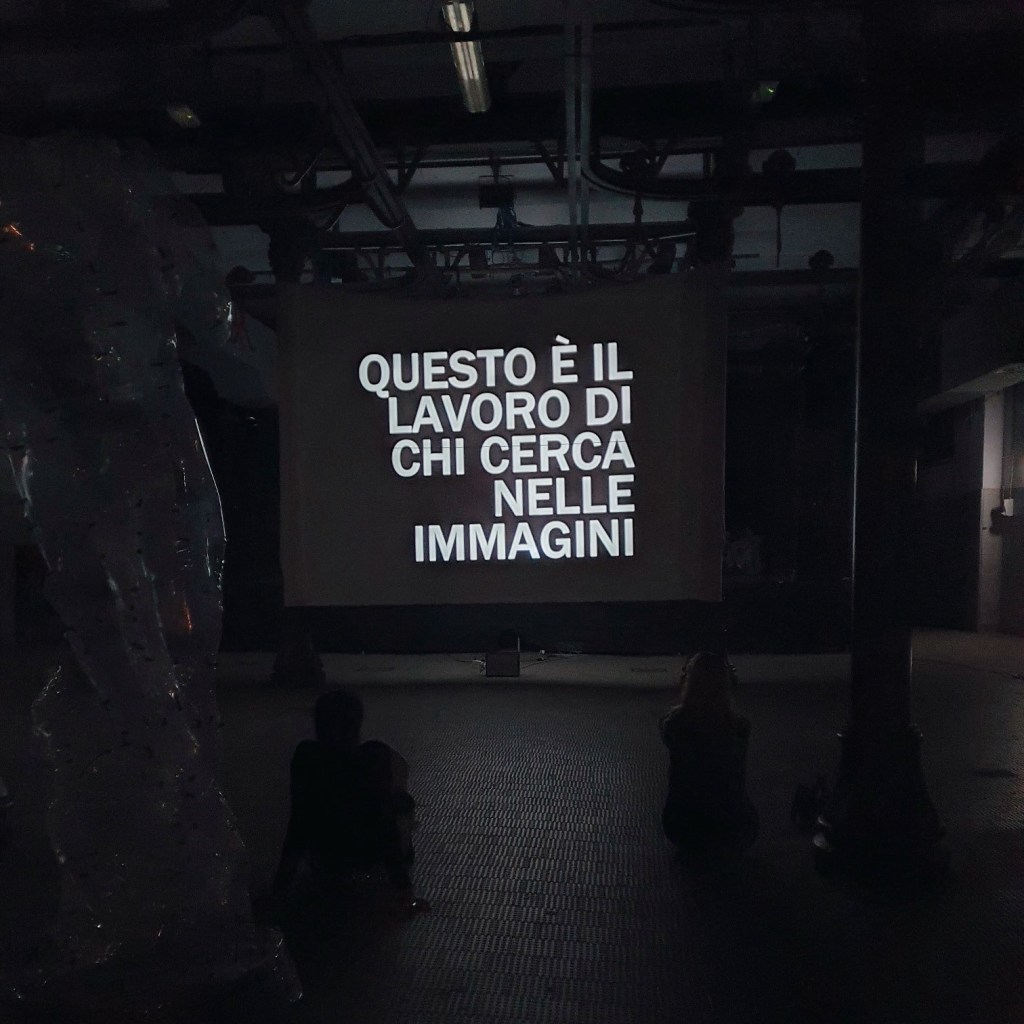

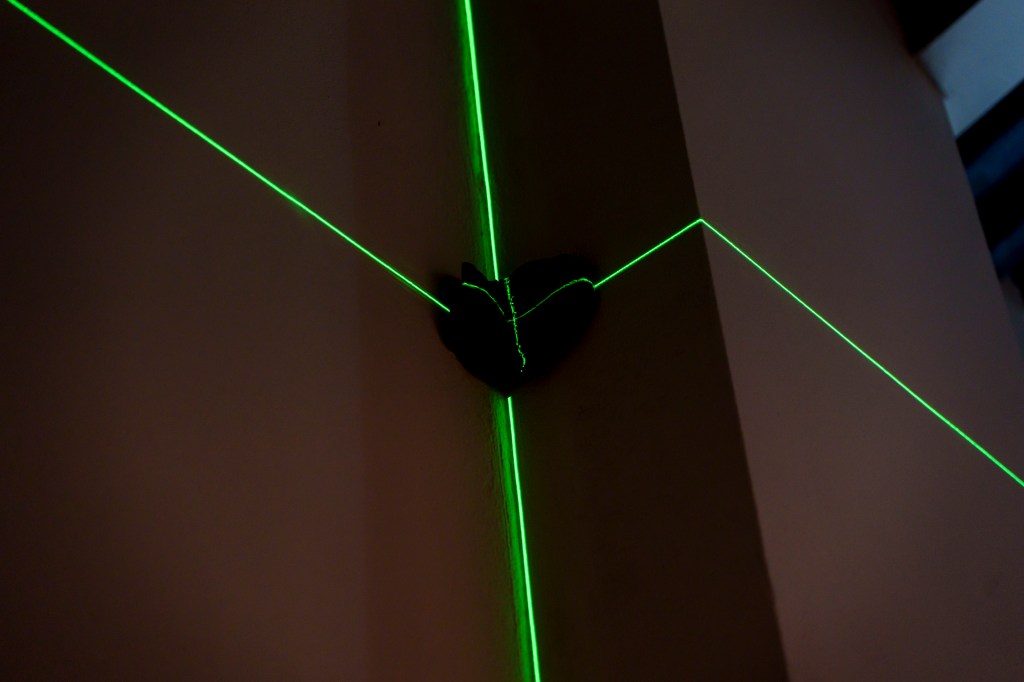

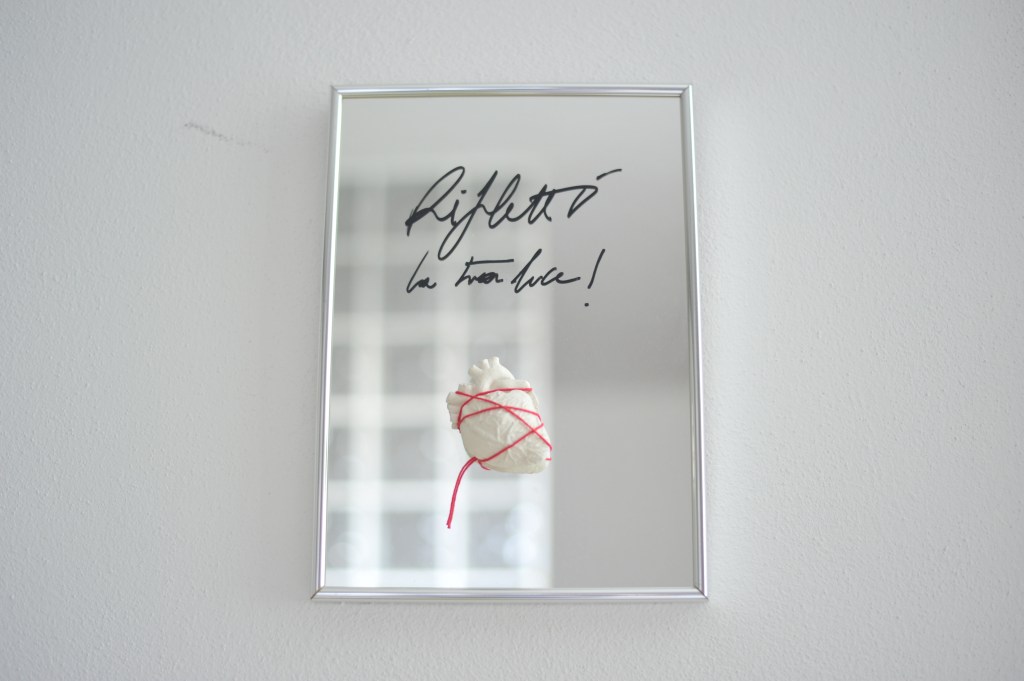

ER: Sì, senza dubbio ho un debole per la fotografia, la performance ed i linguaggi ibridi, ma si tratta di preferenze del tutto personali, le quali possono anche non incidere sul piano professionale quando mi approccio a qualcosa che attira la mia attenzione, che in genere contiene sempre una bella dose di complessità dietro un aspetto semplice ed essenziale. Bisogna che si inneschi una sorta di “innamoramento”, passami il termine, in cui ne è certamente un esempio l’unione altamente funzionale ed efficace tra dimensione concettuale e tridimensionale, come il corpo e/o la scultura che entrano nello spazio prendendovi un posto e assumendo una posizione.

Pd’A: In che modo ti avvicini al lavoro di un’artista?

ER: Sono curiosa e la curiosità è una componente davvero importante per avvicinarmi più o meno alla ricerca di un artista. Un’osservazione attenta è però il primo dato che mi permette di intuire quella complessità di cui accennavo e che al contempo stimola la mia curiosità, che è soprattutto di natura intellettuale. Scelgo così in un secondo momento di avvicinarmi al lavoro attraverso la pratica dello studio visit, che mi offre l’occasione di incontrare l’artista nel suo spazio di riflessione e produzione, e di conoscere da vicino la sua pratica, instaurando un dialogo fatto di ascolto e condivisione di punti di vista.

Pd’A: Della pratica dello studio visit si fa un gran parlare, tu come la intendi?

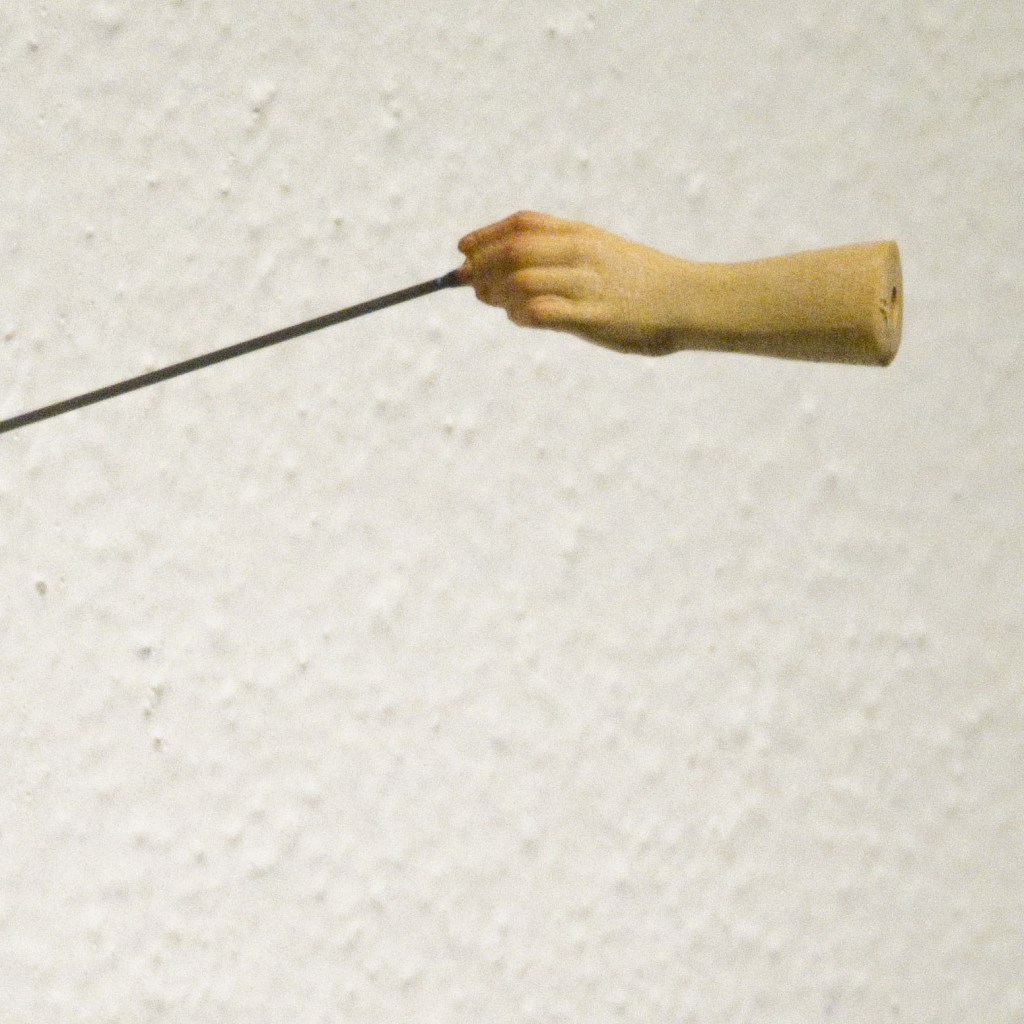

ER: Hai ragione, è un argomento forse abusato e quando di una cosa se ne fa un gran parlare, mi capita di dubitare se si sappia davvero cosa sia. Per quanto anch’io nutra costantemente dubbi sul mio operare per l’abitudine di mettermi in discussione, preferisco andare ai fatti, poiché intendo lo studio visit uno dei momenti più preziosi e importanti che sottende la mia stessa pratica curatoriale. In generale, infatti, intendo lo studio visit un “fare insieme parlando”, una cura della e nella conversazione che inizia dall’occasione di incontrare l’artista nello studio dove questi riflette e opera. Ciò prevede, anzitutto, il voler trovare un tempo che l’artista ed io dedichiamo insieme a questa visita, destinata alla conoscenza del lavoro in sé, di quali spazi questo abbia bisogno per realizzarsi e da quali urgenze personali è generato. Si tratta di un primo approccio che permette di studiare, appunto, e accedere ad un livello più profondo e specifico, ossia al modo in cui l’artista si muove e si relaziona nello spazio che si è scelto e costruito e, soprattutto, a quelli che sono i processi intellettuali e creativi propri della persona: dalle ispirazioni alla poetica in generale alle più profonde intenzioni e connessioni con altri piani o ambiti culturali o, ancora, alla delucidazione di tecniche e prassi che delimitano e determinano le formalizzazioni perseguite dall’artista stesso nelle proprie scelte. Vorrei però precisare che lo spazio può anche essere un proiettore, lo schermo di un computer poggiato sul tavolino di un bar, un hangar o un vasto ambiente all’aperto, non immaginiamoci solo le quattro mura di una stanza. Ad ogni modo, quello dello studio visit lo sento un tempo delicato, in cui ho spesso l’impressione di entrare nella cosiddetta “stanza del vasaio”, usando una metafora biblica, dove, da esterno, qualcuno accede in quella stanza segreta e sotterranea in cui l’artista di solito si trova solo con se stesso, i suoi pensieri e la materia informe che attende il suo gesto. Si entra per osservare, in uno spazio dal perimetro definito e più o meno organizzato che talvolta appare come una mente o un corpo esteso e plastico dell’artista, dove questi non solo espone all’altro opere finite o ritenute tali, ma dove affiorano strumenti e indizi di precise procedure e abitudini, dove si intuiscono nascondigli per oggetti che sono giochi fini a se stessi, tentativi ironici o rompicapo, scarti che oscillano tra prove ed errori, fallimenti o pentimenti quasi mai rinnegati, distrutti o abortiti, ma solo temporaneamente dimenticati in attesa dell’eureka, dell’attimo proficuo. In questo luogo, dove cerco di entrare in punta di piedi, possono nascere allora intesa e complicità intellettuale, in un incontro o scontro tra divergenze di opinioni ugualmente fruttuose, e dove, in ogni caso, al di là di preferenze o orientamenti professionali, la pratica dello studio visit dovrebbe essere condotta con sacro rispetto e accoglienza, senza pregiudizio, per favorire comprensione e reciproca fiducia, le quali possono ampliare lo sguardo critico e contribuire allo sviluppo del processo, favorendo eventuali progettualità condivise. Tutte cose che permettono di far sì che lo studio visit talvolta non si risolva in un momento unico e isolato, ma che diventi un insieme di tanti appuntamenti, portando avanti il filo di un discorso che si lascia e si riprende ogni volta.

Pd’A: Oggi secondo te ha ancora senso parlare di critico militante e che differenza c’è secondo te con la figura del curatore (il fatto che ci sia qualcuno che cura presuppone che ci sia un malato?)?

ER: Questa è una delle domande che tempo fa, insieme a delle colleghe con cui collaboro e condivido sogni e progetti (Silvia Bellotti per Forme e Stefania Rinaldi per CUT | Circuito Urbano Temporaneo), abbiamo proposto ad un evento che prevedeva una serie di Oxford talks. Si tratta di dibattiti e sfide a tempo tra curatori, critici e artisti per accendere i riflettori su temi, situazioni e contesti scomodi e paradossali del sistema dell’arte, di un mondo spesso preda dei suoi più o meno esilaranti mutamenti. Chi partecipava alle sfide, pensate a squadre o singole, doveva far valere la sua posizione convincendo una giuria pubblica che votava con “applausometro” attraverso la propria abilità oratoria. La domanda sulla differenza tra la figura del critico militante e del curatore ha acceso un dibattito che ha tenuto banco più a lungo del previsto, con grande divertimento di tuttə. Tra provare ad elencare differenze ed entrare nel cortocircuito delle somiglianze, non era necessario che chi teneva una delle due posizioni vi aderisse seriamente, ci credesse o meno insomma, contava solo essere convincenti e applicare una strategia comunicativa efficace, come alcuni avvocati che non fanno distinzione tra difendere un innocente o un colpevole presunti tali. Ripensandoci oggi, questo gioco delle parti metteva bene in luce le criticità esistenti tra queste due figure a tratti pantagrueliche, ossia grandi mangiatori-oratori, avidi di panegirici, voli pindarici e citazionismi. Quel che sto per scrivere, infatti, sembra quasi un’invettiva contro entrambe le categorie, compresa quella in cui maggiormente mi riconosco, ma bisogna passare necessariamente dal constatare le differenze attraversando lo shock culturale che avviene nel passaggio tra l’una e l’altra parte, per compiere delle scelte di senso, che diano un orientamento specifico alla propria professione. A dimostrazione di una fame pantagruelica condita di discorsi, ci sto girando intorno, lo so, affondando il tutto nella noia di parole e riccioli decorativi non richiesti. Vengo al dunque, allora, e se una decina di anni fa mi definivo un critico (non militante) con poca contezza della cosa, oggi, invece, affermo di essere una curatrice. Dal maschile generico al femminile che mi è proprio sono passata da una pratica della parola, che si serve dell’opera e dell’artista, schierandosi per affermare e definire un orientamento o una corrente, partecipando alla vita intellettuale con spirito di giudizio, positivo o negativo che sia, più orientata alla produzione di saggi e articoli ecc., ad una cura che si pone a servizio dei processi e del processo creativo in sé della pratica artistica, con una selezione progressiva che individua contesti, allestimenti e mediazione comunicativa a più livelli. Sebbene critica e curatela, in realtà, credo che oggi si completino e si compenetrino a vicenda, le dinamiche culturali e sociali in continuo rinnovamento non fanno altro che rispecchiare le proprie intenzioni e funzioni maggiormente in questa figura detta curatoriale, indicando con essa una pratica complessa e al contempo flessibile, capace di gestire la complessità stessa insita nel contemporaneo e nel sistema odierno dell’arte, quale piattaforma mobile e dalle molte variabili non sempre prevedibili. La curatela, dunque, si muove come una pratica intellettuale (affermazione quasi ossimorica) e si pone come facilitatrice di processi, tessendo insieme rapporti logici non lineari tra attività culturale e letteraria (quando non limitata alle sole battute di un concept), ma anche di selezione, valorizzazione e promozione, offrendo supporto e mediazione, impalcature concettuali e connessioni. In definitiva, credo che non ci sia proprio nessuno da curare, perché altrimenti temo che dovremmo esserlo un po’ tuttə, mi piace invece associare il termine curatela più spesso all’inglese care, il quale, portando con sé significati come “m’interessa”, “preoccuparsi di”, “supportare”, “portare attenzione”, “avere a cuore”, aderisce con una sensibilità più affine ad una forma di militanza critica che, prima di agire, sa mettersi in ascolto. Aggiungerei che la curatela, in tal senso, è un utile esercizio di formazione e affinamento della propria coscienza critica, un conoscere per saper riconoscere.

Pd’A: Una forma empatica?

ER: No, direi di no. L’empatia non è che una delle diverse caratteristiche dell’intelligenza emotiva che, se non accompagnata dalle altre, ricopre una funzione minima e marginale. Empatia come sinonimo di ascolto e capacità di mettersi nei panni dell’altro, inoltre, fosse anche solo questo, dovrebbe essere una competenza trasversale a quasi ogni tipo di professione. Dunque no, non ritengo che sia pertanto una caratteristica propria, a sua volta, dell’attività curatoriale. Se c’è è di sicuro un plus di grande aiuto nello sviluppare sensibilità rispetto alla comprensione di ciò e di chi ci circonda, ma può non essere, in certi casi, un fatto saliente. Tuttavia, mi scuso per aver deviato io stessa la conversazione in questa direzione, facendo sembrare la cosa una sorta di terapia di mutuo soccorso o ascolto psicoanalitico, dando come assodati, invece, altri aspetti sostanziali che ritengo propri della curatela. Dobbiamo allora tornare alla critica di cui la curatela si nutre, intesa quale atto che apre e separa le diverse parti di una data realtà con l’intenzione di osservare, leggere e giudicare, realizzando, da questa triade, una sintesi: saper vedere per saper scegliere. La critica d’arte, al suo atto di nascita, al di là delle feroci invettive affidate a pennino e calamaio, si occupava e si occupa di analisi di produzione estetica, selezione e valutazione (qualitativa e quantitativa), proponendo una visione dell’opera d’arte che parte dalla sua lettura, comprendendo in essa ricerche e conoscenze circa le storie personali dell’artista e la storia generale del contesto sociale in cui questi si trova ad operare e a intessere interessi. Prima ancora di avanzare interpretazioni che possono essere molteplici, soggettive e quasi tutte plausibili, la critica individua e decodifica il linguaggio visivo per dare parola e voce all’immagine attraverso una lettura “intelligente”, ossia capace di vedere/leggere dentro la realtà dell’opera e del suo autore (ove possibile), che si compie poi in un’operazione di sintesi e di selezione. A mio parere, dunque, la curatela raccoglie questa eredità legata al giudizio estetico in quanto tale del fenomeno artistico, ampliando con approfondimenti propri dell’attuale cultura visuale, e la declina in altre forme di impegno concreto e organizzato nei confronti dell’artista e dei suoi interlocutori: una pratica di mediazione, infine, che ha a che fare da una parte più con l’immaginazione e la relazione che ingaggia e attiva gli attori del dialogo mentre, dall’altra, di creare strutture reticolari capaci di costruire percorsi e progetti calati in spazi, tempi e contesti credibili, come quando si passa dall’idea alla forma attraverso il limite della materia, considerando il compromesso ragionevole con la realtà.

Pd’A: Il che sembra porre il curatore su un piano non troppo dissimile da quello in cui si pone l’artista?

ER: La tua domanda mi permette una riflessione su tutte le professioni cosiddette art-based e che si fondano su processi, principi e metodologie tra loro simili, in quanto afferenti al campo esteso della creatività, per la quale preferisco offrire la definizione di uno studioso come Howard Gardner, il quale ha tentato di comprendere a fondo, per gran parte della sua vita da ricercatore, i processi che sottendono l’apprendimento delle diverse arti e attività artistiche. Gardner afferma che la creatività è da intendere come quella “capacità umana che consente regolarmente di risolvere problemi e modellare prodotti in campi specifici, in modo tale che inizialmente risulta nuovo, ma alla fine accettabile entro un data cultura”. Pertanto, per rispondere alla tua domanda, dirò che certamente artista e curatore possono essere posti sullo stesso piano, interlocutorio, proattivo e di discussione dialogica tra parti, ma con ruoli e competenze tra loro molto differenti per il raggiungimento di “prodotti culturali”, ad esempio opere, progetti espositivi, pubblicazioni, ecc., individuati come obiettivi comuni (o almeno in molti casi). Ci sarebbe poi da dire, inoltre, che sebbene esistano artisti-curatori e curatori-artisti che hanno conoscenze, abilità e competenze altamente professionalizzanti in ambo le vesti, considero questi una grande ed eccezionale rarità che ha a che fare con le singole persone, i loro interessi e passioni, bisogni e propensioni specifiche, a cui si aggiungono percorsi formativi e biografici altamente personalizzati. Temo, infatti, al di là di tali eccezioni, che se ogni professione possa essere appresa e praticata, nessuno possa dire di se stesso di “fare” l’artista e porsi allo stesso piano di chi lo è, poiché ritengo che non esista un “fare l’artista” ma solo un “essere artista”, con tutte le difficoltà annesse del caso, con tutto il “travaglio” e i piaceri del divenire di questa possibile scoperta.

Pd’A: Sono assolutamente d’accordo. Ora ti volevo chiedere di parlare del lavoro che svolgi per la Fondazione Italo Bolano?

ER: Parlare della Fondazione Italo Bolano è per me sempre un grande piacere così come lo è il lavoro che svolgo per questa realtà, che reputo al contempo un onore e un onere. Consentimi però una piccola digressione, di natura narrativa, per introdurre brevemente la Fondazione e comprendere meglio il mio ruolo al suo interno. La Fondazione nasce nel 2021 a seguito della scomparsa di Italo Bolano (Portoferraio, 1936 – Prato, 2020), espressionista astratto poliedrico e ricercatore instancabile, al fine di gestire lo storico Open Air Museum all’Isola d’Elba, un giardino all’aperto con una collezione permanente di opere ceramiche e sculture in acciaio e vetro dallas – festeggiando quest’anno ben 60 anni di attività -, e il nuovo Open Studio di Prato, ex atelier dell’artista inaugurato nel 2022 come spazio espositivo e luogo di ricerca. La Presidente Alessandra Ribaldone, nonché compagna di vita e d’arte di Bolano, è riuscita così nell’intento di custodire e dare continuità all’eredità artistica e umana che le è stata lasciata e che con generosità non ha voluto tenere solo per sé. La mia nomina a Direttrice artistica della Fondazione è arrivata subito, all’atto di inizio, in quanto depositaria silenziosa dell’ultimo decennio dell’attività artistica di Bolano. Il mio lavoro, pertanto, oggi si muove su un’unica direttrice, che è quella formulata negli anni ‘60 da Bolano e che abbiamo assunto nel nostro statuto, ossia favorire l’incontro tra Arte e Natura e lo scambio tra pubblici grazie alla promozione dei diversi linguaggi del contemporaneo, ma con compiti che dispiegano le loro forze in azioni di duplice natura. Anzitutto, il mio compito è di garantire la tutela, la conservazione e la conoscenza del patrimonio dell’artista, con interventi che vanno al di là di regolari esposizioni della sua ricca produzione, come, ad esempio, riprogettazione dei percorsi museali e ricerca contributi per il miglioramento dei servizi e delle diverse attività che la Fondazione svolge, anche in collaborazione con il sistema museale di cui il museo elbano fa parte, ossia SMART – Sistema Museale dell’Arcipelago Toscano, in quanto membro del comitato scientifico. In secondo luogo mi occupo di scouting di artisti emergenti e non solo, e di ricerca sul territorio per proporre e costruire progetti espositivi e residenze d’artista in linea con i principi statutari e che possano continuare a mantenere forte il legame tra Isola d’Elba e “continente” (come gli isolani usano chiamare la terraferma), così come lo è stato per Bolano lungo l’intero arco della sua vita. L’intenzione è far sì che la Fondazione possa essere un ponte creativo che permetta l’incontro, il dialogo e lo scambio tra tante realtà diverse tra loro al fine di “iniziarsi alla conoscenza” (cit. I. Bolano); mentre nei confronti degli artisti, soprattutto, l’obiettivo è proporsi come piattaforma di ricerca e sperimentazione, mettendo in campo risorse per consentire di elaborare e produrre partendo da sollecitazioni che altrimenti non sarebbero state possibili.

Pd’A: L’attività della Fondazione si diversifica sulle due sedi Prato/Elba?

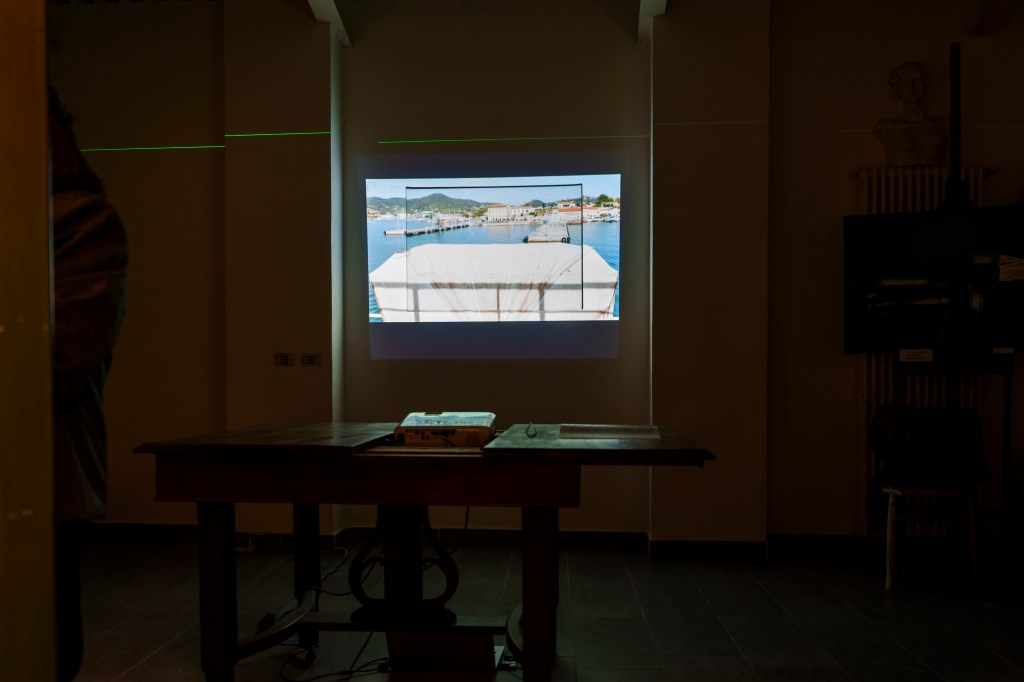

ER: Sì, esattamente. La diversificazione delle attività tra le due sedi è legata non solo al territorio di riferimento e ai diversi obiettivi e funzioni per cui sono nate le due sedi, ma anche al periodo di apertura, che rispetta inoltre l’esatta alternanza con cui Italo Bolano li viveva personalmente. L’Open Air Museum all’Isola d’Elba, infatti, è anzitutto un giardino all’aperto, votato per questo alla bella stagione. Storicamente apre il primo maggio di ogni anno e chiude a settembre, fino a che il tempo permette lo svolgersi di tutte le iniziative che animano i diversi spazi del giardino, che Bolano stesso aveva previsto e dedicato all’incontro tra le arti e i pubblici: oltre alla collezione e ai suoi percorsi, sin dall’origine sono presenti, infatti, un teatro sotto le stelle, una piattaforma per proiezioni, una tettoia e altri ambienti per il ristoro, spazi laboratoriali con un forno per la ceramica raku e una galleria quale unico ambiente al chiuso, oltre alla casa per gli artisti e all’ex studio estivo di Bolano (quest’ultimo al momento chiuso al pubblico). Il museo diventa una piazza viva e multiforme di giorno e di notte, per incontri, presentazioni di libri, conferenze, laboratori didattici, rappresentazioni teatrali, concerti e molto altro. Dell’apertura e del calendario delle iniziative legate alle collaborazioni locali si occupa con indefessa dedizione la Presidente che da Prato si trasferisce al museo per l’intero arco di tempo, così come faceva insieme al marito. Io, invece, mi stabilisco sull’isola per periodi medio-lunghi per curare i progetti di residenza, le mostre temporanee e ciò che concerne le diverse necessità della collezione e della sua fruizione. L’Open Studio di Prato, al contrario, copre i mesi che vanno da ottobre a maggio (prolungandosi su giugno), con una programmazione a mia cura che segue annualmente un filone tematico e sul quale vengono cucite, in alternanza, mostre dedicate alla conoscenza della produzione pittorica di Italo Bolano e mostre che promuovano, invece, la produzione di altri artisti, offrendo uno spazio di libertà e relazione con una storia così significativa per noi, che però non è mai, e non vuole esserlo, vincolante per chi ospitiamo, invitato a presentare il proprio lavoro anche attraverso modalità inedite o alternative. L’Open Studio, oltretutto, non vuole essere solo uno spazio espositivo, ma anche un luogo aperto al confronto e al dialogo, un salotto culturale, insomma, all’interno del quale stiamo cercando anche di proporre, pian piano, ascolti musicali, incontri laboratoriali, conferenze sulle arti, presentazioni di libri con una particolare attenzione a pubblicazioni che hanno una certa rilevanza in merito alla scrittura creativa, il tutto per accendere dibattiti, innescare conversazioni, stimolare nuove idee e, magari, visioni collettive.

English text

Intervista a Erica Romano

#paroladartista #intervistacritica #artcritcinterview #ericaromano

Parola d’Artista: Hi Erica, when, how and why did you start working with art?

Erica Romano: Hi, ‘the when’ is lost in an indecipherable, fluctuating, uncertain and perhaps unconscious time. ‘The how’ and “the why” I believe are an inevitable consequence, but both driven by a strong desire for knowledge, driven by curiosity to explore human creative intelligence in all its expressions. The first was a university internship that I had strongly desired at the Export Office of the Superintendency of Florence, because I was interested in seeing up close the ‘behind the scenes’ of how those much-loved works of art that I considered ‘untouchable’ are moved, handled and travelled; the second was the need to change direction from the idea of feeling like a pawn in the hands of those cumbersome cogs of academic life. And so, as I was about to graduate from the Faculty of Art History on the Pisan lungarni, I began to frequent cultural associations and circles between Prato and Florence, because I wanted and needed to meet, share reflections, and have a more concrete and close, tangible relationship with different protagonists and realities that acted within the contemporary art scene, exploring contexts, meeting operators, artists, and audiences. I was beginning to understand that ‘dealing with art’ meant ‘dealing with people’.

Pd’A: Who were the people you frequented?

ER: I mostly hung out with artists, some of whom were already established and to whom I really owe a lot, because they passed on part of their rich experience, sharing their vision of the world through their art. I then started to go elsewhere, to other venues such as Milan and Rome, or other shores such as Switzerland, where I was able to encounter new stimuli and ways of working, getting to know more or less structured organisations, independent spaces, sector magazines and young artists whose research revolved around the interpenetration of electronic music, performance, dance and photography. Lastly, frequenting certain associations played an important role in terms of the value of participation and the pooling of ideas and interests to be finalised in cultural activities, a path that has now led me to choose to collaborate on a permanent basis with some of these associations for educational and curatorial planning. I should be able to trace the profile of many faces, but I believe that in everyone’s life there is a long gallery of portraits, more or less loved and known, which have contributed in different ways to the definition of their professional and other identities.

Pd’A: In the babel of languages in contemporary art, is there anything that attracts you the most?

ER: Yes, I undoubtedly have a weakness for photography, performance and hybrid languages, but these are entirely personal preferences, which may not even affect me professionally when I approach something that attracts my attention, which generally always contains a fair amount of complexity behind a simple and essential aspect. A sort of ‘falling in love’, if you will pardon the term, must be triggered, where the highly functional and effective union of the conceptual and three-dimensional dimensions, such as the body and/or sculpture entering the space and taking up a position in it, is certainly an example.

Pd’A: How do you approach the work of an artist?

ER: I am curious, and curiosity is a really important component in approaching an artist’s work. However, careful observation is the first thing that allows me to perceive that complexity I mentioned and at the same time stimulates my curiosity, which is above all of an intellectual nature. I thus choose at a later stage to approach the work through the practice of the studio visit, which offers me the opportunity to meet the artist in his space of reflection and production, and to get to know his practice closely, establishing a dialogue made up of listening and sharing points of view.

Pd’A: There’s a lot of talk about the practice of the studio visit, how do you understand it?

ER: You’re right, it’s a topic that is perhaps abused, and when there’s a lot of talk about something, I find myself questioning whether we really know what it is. As much as I also constantly have doubts about my work because of my habit of questioning myself, I prefer to go to the facts, because I understand the studio visit as one of the most precious and important moments that underlies my own curatorial practice. In fact, in general, I understand the studio visit as a ‘doing together by talking’, a curation of and in conversation that begins with the opportunity to meet the artist in the studio where he reflects and works. This involves, first of all, the artist and I dedicating time together to this visit, which is intended to get to know the work itself, what spaces it needs to realise itself and from what personal urgencies it is generated. This is a first approach that allows us to study and access a deeper and more specific level, that is, the way in which the artist moves and relates in the space that he has chosen and constructed for himself and, above all, what are the intellectual and creative processes proper to the person: from inspirations to poetics in general to the deepest intentions and connections with other levels or cultural spheres or, again, to the elucidation of techniques and practices that delimit and determine the formalisations pursued by the artist himself in the one’s own choices. However, I would like to point out that the space can also be a projector, a computer screen resting on a coffee table, a hangar or a vast open-air environment, let’s not just imagine the four walls of a room. In any case, that of the studio visit I feel is a delicate time, in which I often have the impression of entering the so-called ‘potter’s room’, to use a biblical metaphor, where, from the outside, someone enters that secret, underground room where the artist usually finds himself alone with himself, his thoughts and the formless matter awaiting his gesture. One enters to observe, in a space with a defined and more or less organised perimeter that sometimes appears as a mind or an extended and plastic body of the artist, where he not only exhibits finished works or those considered as such to others, but where tools and clues to precise procedures and habits emerge, where hiding places for objects that are games in themselves, ironic attempts or puzzles, discards that oscillate between trials and errors, failures or repentances that are almost never repudiated, destroyed or aborted, but only temporarily forgotten while waiting for the eureka, the profitable moment. In this place, where I try to enter on tiptoe, intellectual understanding and complicity can then be born, in a meeting or clash of equally fruitful differences of opinion, and where, in any case, beyond professional preferences or orientations, the practice of The studio visit should be conducted with sacred respect and welcome, without prejudice, to foster understanding and mutual trust, which can broaden the critical gaze and contribute to the development of the process, favouring possible shared projects. These are all things that make it possible for the study visit sometimes not to be resolved in a single, isolated moment, but to become a collection of many appointments, carrying on the thread of a discourse that is left and taken up again each time.

Pd’A: In your opinion, does it still make sense today to speak of a militant critic, and what difference do you think there is with the figure of the curator (does the fact that there is someone who curates presuppose that there is a sick person?)?

ER: This is one of the questions that some time ago, together with some colleagues with whom I collaborate and share dreams and projects (Silvia Bellotti for Forme and Stefania Rinaldi for CUT | Circuito Urbano Temporaneo), we proposed at an event that included a series of Oxford talks. These were debates and timed challenges between curators, critics and artists to turn the spotlight on uncomfortable and paradoxical themes, situations and contexts of the art system, of a world often prey to its more or less exhilarating changes. Those who took part in the challenges, conceived as teams or individuals, had to make their case by convincing a public jury that voted by ‘applauseometer’ through their oratorical skills. The question of the difference between the figure of the militant critic and that of the curator sparked a debate that lasted longer than expected, much to the amusement of allə. Between trying to list differences and entering into the short circuit of similarities, it was not necessary for those who held one of the two positions to seriously adhere to it, to believe in it or not, all that mattered was to be convincing and apply an effective communication strategy, like some lawyers who make no distinction between defending an innocent or a guilty person allegedly guilty. Thinking back on it today, this game of the parts nicely highlights the criticality that exists between these two pantagruelic figures, i.e. great eaters-worshipers, eager for panegyrics, Pindaric flights and citations. What I am about to write, in fact, almost sounds like an invective against both categories, including the one in which I most recognise myself, but one must necessarily move on from noting the differences by going through the culture shock that occurs in the transition between one and the other, in order to make choices of meaning, which give a specific orientation to one’s profession. Demonstrating a pantagruelic hunger seasoned with discourse, I am going round and round, I know, sinking it all into the boredom of words and unsolicited decorative curlicues. I come to the point, then, and if a decade ago I defined myself as a (non-militant) critic with little knowledge of the subject, today, on the other hand, I claim to be a curator. From the generic masculine to the feminine I have moved from a practice of the word, which makes use of the work and the artist, taking sides to affirm and define an orientation or a current, participating in intellectual life with a spirit of judgement, whether positive or negative, more oriented towards the production of essays and articles etc., to a curatorship that places itself at the service of the processes and the creative process in itself of artistic practice, with a progressive selection that identifies contexts, settings and communicative mediation at various levels. Although criticism and curatorship actually complement and interpenetrate each other today, I believe that the ever-changing cultural and social dynamics only reflect their intentions and functions more in this figure known as the curator, indicating with it a complex yet flexible practice, capable of managing the very complexity inherent in the contemporary and in today’s art system, as a mobile platform with many variables that are not always predictable. Curatorship, therefore, moves as an intellectual practice (an almost oxymoronic statement) and acts as a facilitator of processes, weaving together non-linear logical relationships between cultural and literary activity (when not limited to the lines of a concept), but also of selection, valorisation and promotion, offering support and mediation, conceptual scaffolding and connections. In the final analysis, I believe that there is no one to be curated at all, because otherwise I fear we would all have to be curated. Instead, I like to associate the term curatorship more often with the English word care, which, carrying with it meanings such as ‘I care’, ‘to be concerned about’, ‘to support’, ‘to bring attention to’, ‘to care about’, adheres with a sensitivity more akin to a form of critical militancy that, before acting, knows how to listen. I would add that curating, in this sense, is a useful exercise in training and refining one’s critical conscience, a knowing in order to know how to recognise.

Pd’A: A form of empathy?

ER: No, I would say not. Empathy is but one of several characteristics of emotional intelligence that, if not accompanied by the others, plays a minimal and marginal function. Empathy as a synonym for listening and the ability to put oneself in the other person’s shoes, moreover, if only that, should be a transversal competence in almost every profession. Therefore, no, I do not believe that it is, in turn, a characteristic of curatorial activity. If it is there, it is certainly a great plus in developing sensitivity with respect to understanding what and who is around us, but it may not be, in certain cases, a salient fact. However, I apologise for diverting the conversation in this direction myself, making it sound like a kind of mutual aid therapy or psychoanalytic listening, while giving as established, instead, other substantial aspects that I consider proper to curating. We must then return to the criticism on which curatorship feeds, understood as an act that opens up and separates the different parts of a given reality with the intention of observing, reading and judging, realising, from this triad, a synthesis: knowing how to see in order to know how to choose. Art criticism, at its birth, beyond the fierce invectives entrusted to the pen and inkwell, was and is concerned with the analysis of aesthetic production, selection and evaluation (qualitative and quantitative), proposing a vision of the work of art that starts from its reading, including in it research and knowledge about the artist’s personal history and the general history of the social context in which he or she operates and weaves interests. Even before advancing interpretations that may be multiple, subjective and almost all plausible, the critic identifies and decodes the visual language in order to give word and voice to the image through an ‘intelligent’ reading, i.e. capable of seeing/reading within the reality of the work and its author (where possible), which is then carried out in an operation of synthesis and selection. In my opinion, therefore, curatorship takes up this inheritance linked to the aesthetic judgement as such of the artistic phenomenon, expanding it with insights proper to current visual culture, and declines it into other forms of concrete and organised engagement with the artist and his interlocutors: a practice of mediation, finally, which has to do on the one hand more with the imagination and the relationship that engages and activates the actors in the dialogue while, on the other hand, creating reticular structures capable of constructing paths and projects set in credible spaces, times and contexts, as when one goes from idea to form through the limit of matter, considering the reasonable compromise with reality.

Pd’A: Which seems to place the curator on a plane not too dissimilar from that on which the artist places himself?

ER: Your question allows me to reflect on all the so-called art-based professions that are based on similar processes, principles and methodologies as they pertain to the extended field of creativity, for which I prefer to offer the definition of a scholar such as Howard Gardner, who has tried for much of his life as a researcher to understand in depth the processes underlying the learning of different arts and artistic activities. Gardner states that creativity is to be understood as that ‘human capacity that regularly enables us to solve problems and shape products in specific fields, in such a way that it is initially new, but ultimately acceptable within a given culture’. Therefore, to answer your question, I would say that certainly artist and curator can be placed on the same level, interlocutive, proactive and in dialogical discussion between parties, but with very different roles and competences for the achievement of ‘cultural products’, e.g. works, exhibition projects, publications, etc., identified as common goals (or at least in many cases). It should also be said, moreover, that although there are artist-curators and curator-artists who have highly professionalised knowledge, skills and competences in both capacities, I consider these to be a great and exceptional rarity that has to do with individual persons, their interests and passions, specific needs and propensities, to which highly customised training and biographical paths are added. I fear, in fact, beyond these exceptions, that if every profession can be learnt and practised, no one can say of themselves that they ‘do’ the artist and put themselves on the same level as those who are, because I believe that there is no such thing as ‘doing the artist’ but only ‘being an artist’, with all the annexed difficulties of the case, with all the ‘labour’ and the pleasures of becoming this possible discovery.

Pd’A: I absolutely agree. Now I wanted to ask you to talk about the work you do for the Italo Bolano Foundation?

ER: Talking about the Italo Bolano Foundation is always a great pleasure for me, as is the work I do for it, which I consider to be both an honour and a burden. Allow me, however, a small digression, of a narrative nature, to briefly introduce the Foundation and better understand my role within it. The Foundation was set up in 2021 following the death of Italo Bolano (Portoferraio, 1936 – Prato, 2020), a multifaceted abstract expressionist and tireless researcher, in order to manage the historic Open Air Museum on the Island of Elba, an open-air garden with a permanent collection of ceramic works and sculptures in steel and dallas glass – celebrating 60 years of activity this year – and the new Open Studio in Prato, the artist’s former atelier inaugurated in 2022 as an exhibition space and place of research. President Alessandra Ribaldone, as well as Bolano’s life and art companion, has thus succeeded in preserving and giving continuity to the artistic and human legacy that has been left to her and that she generously did not want to keep only for herself. My appointment as Artistic Director of the Foundation came immediately, at the very beginning, as the silent custodian of the last decade of Bolano’s artistic activity. My work, therefore, today moves along a single guideline, which is the one formulated in the 1960s by Bolano and which we have assumed in our statute, namely to foster the encounter between Art and Nature and the exchange between publics through the promotion of the different languages of the contemporary, but with tasks that deploy their forces in actions of a dual nature. First of all, my task is to ensure the protection, conservation and knowledge of the artist’s heritage, with actions that go beyond regular exhibitions of his rich production, such as, for example, redesigning museum itineraries and seeking contributions to improve the services and various activities that the Foundation carries out, also in collaboration with the museum system of which the Elban museum is part, i.e. SMART – Sistema Museale dell’Arcipelago Toscano, as a member of the scientific committee. Secondly, I am involved in scouting for emerging artists and others, and in researching the territory in order to propose and construct exhibition projects and artist residencies in line with the statutory principles and that can continue to maintain a strong link between the Island of Elba and the ‘continent’ (as the islanders use to call the mainland), as it has been for Bolano throughout his life. The intention is for the Foundation to be a creative bridge that allows the meeting, dialogue and exchange between many different realities in order to ‘initiate knowledge’ (cit. I. Bolano); while with regard to artists, above all, the aim is to propose itself as a platform for research and experimentation, providing resources to allow them to elaborate and produce from stimuli that would otherwise not have been possible.

Pd’A: Does the Foundation’s activity diversify into the two locations Prato/Elba?

ER: Yes, exactly. The diversification of activities between the two venues is linked not only to the territory of reference and the different objectives and functions for which the two venues were created, but also to the period of opening, which also respects the exact alternation with which Italo Bolano experienced them personally. The Open Air Museum on the Island of Elba, in fact, is first and foremost an open-air garden, devoted for this reason to the fine weather. Historically, it opens on 1 May each year and closes in September, as long as the weather permits all the initiatives that animate the various spaces of the garden, which Bolano himself envisaged and dedicated to the encounter between the arts and the public: in addition to the collection and its paths, from the outset there is a theatre under the stars, a platform for projections, a canopy and other areas for refreshments, workshop spaces with a raku pottery kiln and a gallery as the only indoor environment, as well as the artists’ house and Bolano’s former summer studio (the latter currently closed to the public). The museum becomes a living, multiform piazza by day and by night, for meetings, book presentations, lectures, educational workshops, theatre performances, concerts and much more. The opening and the calendar of initiatives linked to local collaborations are taken care of with indefatigable dedication by the president, who moves from Prato to the museum for the entire time, as she did with her husband. I, on the other hand, stay on the island for medium to long periods to take care of residency projects, temporary exhibitions, and what concerns the various needs of the collection and its use. The Open Studio in Prato, on the other hand, covers the months from October to May (extending into June), with a programme curated by me that annually follows a thematic thread and on which exhibitions dedicated to the knowledge of Italo Bolano’s pictorial production and exhibitions that promote However, this is never, and does not want to be, binding for those we host, who are invited to present their work in new or alternative ways.