(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #domenicoruccia

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui iniziano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Domenico Ruccia: Il disegno è stato sin dai primi tempi uno dei miei interessi principali. Era la mia attività preferita rispetto ai videogiochi e ai cartoni animati, e spesso anche agli amici e compagni di scuola. Mi piaceva e mi piace tuttora stare da solo, e disegnare coniugava questa mia tendenza. Negli anni la cosa è rimasta più o meno inalterata.

Pd’A: Anche tu hai avuto, come molti altri, un primo amore artistico?

DR: Se per amore artistico si intende innamorarsi di un’immagine, penso soprattutto alle copertine dei dischi. Ho iniziato a guardarle sin da piccolo, spulciando gli album dei miei genitori, e curiosando all’interno dei libricini dei cd o delle confezioni dei vinili. Il primo amore artistico in termini di autore sono stati di conseguenza i gruppi musicali, direi in particolare i Queen. C’è questa loro raccolta del 1991, Greatest Hits II, dove in copertina vi è un disegno con la stilizzazione dei segni zodiacali dei componenti del gruppo. Ho saputo dopo anni del significato della composizione, ma ho percepito subito la forza di un segno di racchiudere un significato sottostante.

Pd’A: Quali studi hai fatto?

DR:Finito il liceo scientifico, mi sono iscritto alla facoltà di legge. Dopo la laurea in Giurisprudenza e l’abilitazione alla professione di avvocato, ho cambiato radicalmente strada dedicandomi alla pittura. Ovviamente non è stata una decisione improvvisa, ho sempre continuato a disegnare, ma ho capito allora di voler far solo quello nella vita e ho rischiato.

Pd’A: Ci sono stati incontri importanti durante gli anni della formazione?

DR:Dopo l’abilitazione mi sono iscritto in Accademia di Belle Arti, prima a Bari per il triennio, poi a Brera nel 2018 per il biennio specialistico, ci tenevo molto. In questi anni ho avuto degli incontri importanti. Potrei forse riassumerli nel mio primo maestro, una persona ed un artista speciale a cui sono ancora legato e che mi ha fatto capire di aver del potenziale, e poi in alcuni artisti e professori incontrati a Brera, che mi hanno aiutato a strutturare il lavoro e a creare delle mie regole.

Pd’A: Da dove provengono le immagini che dipingi?

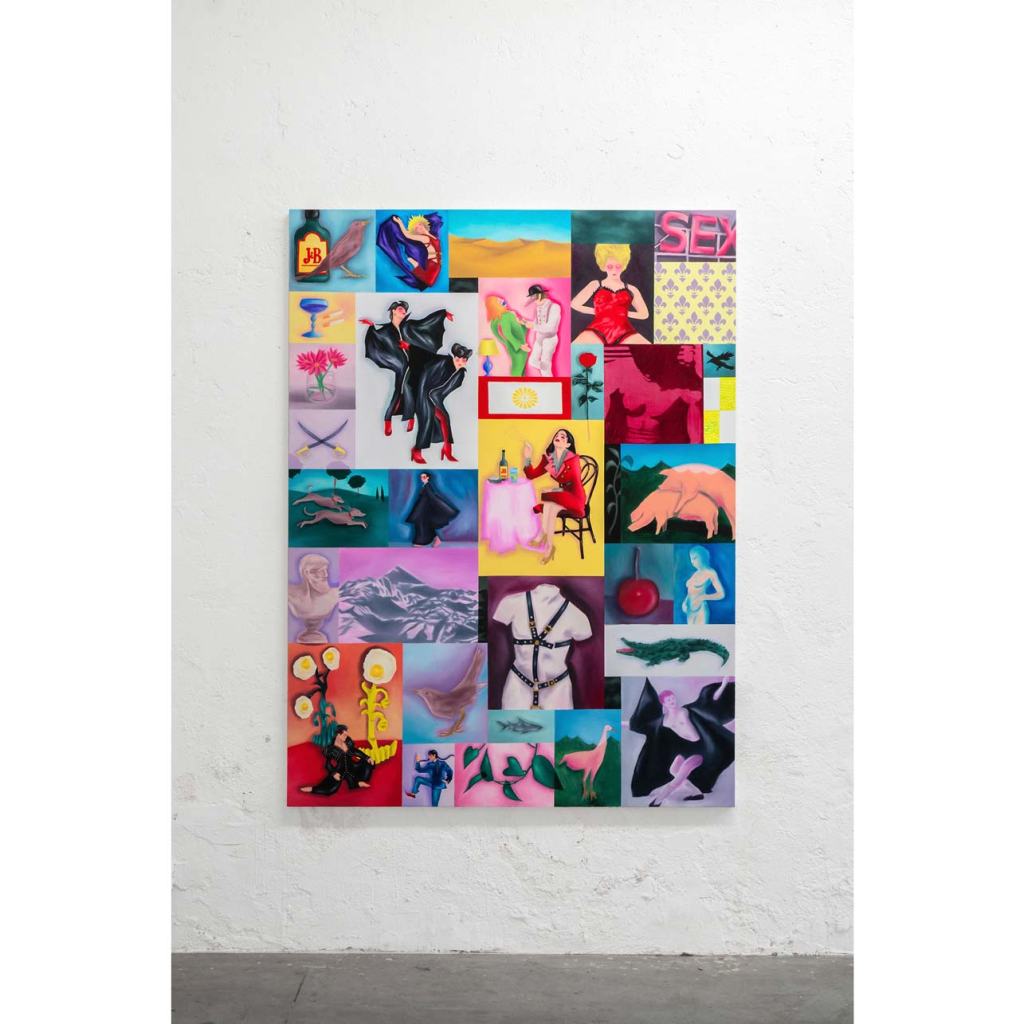

DR: Il mio atlas è cambiato nel corso del tempo. Quando mi sono concentrato sul mondo dello spettacolo degli anni 70’-80’, l’archivio ha inglobato tante immagini di musica, cinema e moda di quegli anni, spingendomi a ricercare riviste d’epoca, archivi specializzati e siti web dai quali attingevo principalmente rarità vintage, che era la cosa che mi affascinava di più. In seguito, ho iniziato a selezionare dei frame di alcune pellicole e spot pubblicitari d’epoca, che sono in parte confluiti nella mia serie di video Spiritus mundi. Queste immagini venivano poi sovrapposte ad altre, sempre presenti nell’archivio, e creavo da questi strani collage delle storie.

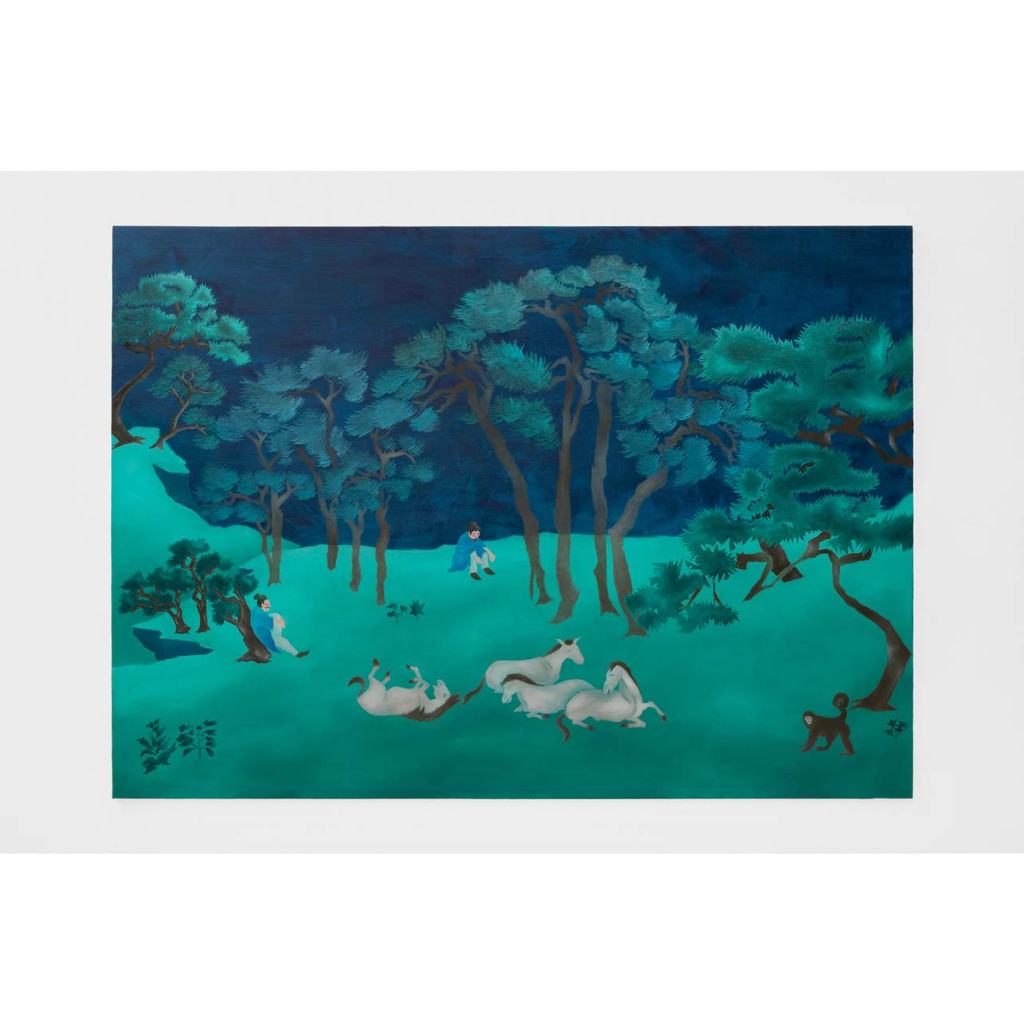

La stessa operazione è stata poi realizzata quando ho iniziato a lavorare alla serie Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes: ho creato una sezione d’archivio con immagini e dettagli di opere tardo gotiche/rinascimentali, alla quale si sono aggiunte altre raccolte sulla grafica e la pittura cinese e giapponese del XV-XVI secolo. L’unione di queste categorie mi ha permesso di creare nuovi collage, che sono poi diventati le storie da raccontare nella nuova serie.

Pd’A: Che cosa ti affascina di Paolo Uccello ed in generale della storia dell’arte?

DR: Sono affascinato dal corso della storia dell’arte e dalle sue evoluzioni, in relazione ai periodi storici e politici di una determinata epoca. È un tema che influisce molto sul mio modo di lavorare, perché mi piace reinterpretare un contesto passato inserendo narrazioni fittizie ma funzionali al mio racconto. È un processo che ho sempre utilizzato. Paolo Uccello è così affascinante perché ha rappresentato forse come nessun’altro la temperatura e l’avanguardia della propria epoca, ma allo stesso tempo, molti secoli dopo, riesce ancora ad entrare prepotentemente nel contemporaneo e a risultare un paradigma per il futuro. Per questa ragione reinterpretare la sua vicenda non è una celebrazione del passato, ma è il mio modo di avere un occhio laterale sulla contemporaneità.

Pd’A: Ti interessa l’idea di racconto?

DR:Per il mio lavoro è essenziale. Utilizzo la pittura quale strumento per esplorare il concetto di tempo e mi piace inventare vicende inedite, frutto della mia fantasia, all’interno di contesti storici realmente esistiti.

Parto sempre da un dato appartenente al passato, e da lì ricostruisco il tutto con l’immaginazione. L’immagine diventa lo strumento per fraintendere la storia, per cambiarla.

Ho utilizzato questo metodo sia nei miei lavori precedenti, che avevano quale focus gli anni 70’ ed 80’, sia nelle serie più recenti, come nei Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes. Qui in particolare ho immaginato delle opere inedite di Paolo Uccello realizzate nel corso di un suo fantomatico viaggio in Estremo Oriente verso la fine della sua vita, che lo stesso artista ha deciso di non mostrare mai. L’ironia della narrazione sottesa al progetto mi è servita per raccontare qualcosa di nuovo. La serie non avrebbe avuto un senso se non ci fosse stata da parte mia la voglia di raccontare, già prima delle opere, questo viaggio nella storia.

Pd’A: Ho visto che talvolta lavori anche con il video realizzando delle immagini in loop, che importanza hanno le categorie di tempo e spazio per te?

DR:Il video mi ha permesso di operare direttamente su quelle che sono le fonti delle immagini che utilizzo in pittura ovvero film, pubblicità, video musicali, documentari ma anche registrazioni fatte con il cellulare. Con Spiritus mundi, una serie di video che ho realizzato tra il 2022 e il 2023, ho giocato con queste fonti come se fossero collage, ritagliandole, riordinandole e reinserendole in ordine non logico, ma funzionale all’opera: sono una serie di immagini prive di audio che si alternano senza soluzione di continuità su un FAN led installato al muro. Rappresentano un potenziamento della mia pittura e un elemento per trarre nuovi spunti, anche perché il supporto che ho utilizzato, un ventilatore luminoso, è essenziale alla riproduzione corretta dell’opera quanto una tela è necessaria per realizzare un dipinto.

Pd’A: Il colore che importanza ha nel tuo lavoro?

DR:La cromia è uno strumento per definire la temperatura di un quadro, allo stesso livello del soggetto, dell’ambientazione o delle linee e delle forme. Nel corso degli anni la mia tavolozza ha subìto tanti cambiamenti. In Piccole dissertazioni di stringente attualità il focus erano gli anni 70’ e 80’, un certo tipo di modernità di cui oggi abbiamo solo l’elemento nostalgico, ed i toni viravano su queste cromie accese, laccate, spesso fuori moda. Con i Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes tutto è svoltato sul pastello, non solo in relazione alla rappresentazione di ciò che stavo dipingendo, come gli alberi e le montagne, ma perché quella tavolozza era per me più funzionale nel riprendere epicamente, ma anche ironicamente, un discorso sul Rinascimento. Direi quindi che il colore ha come prima funzione quella di contestualizzare e di definire gli intenti di un’opera.

Pd’A: Che importanza e che ruolo svolge il disegno in quello che fai?

DR:Molte idee che ho avuto sono nate dal disegno, o sono state concepite con esso. Ci sono stati periodi in cui il dipingere solo con colori e pennelli ha preso il sopravvento, ma è stato temporaneo. Oggi non vedo differenza, utilizzo un segno grafico con pastelli e matite nei miei quadri e spesso il disegno rappresenta sia il passaggio precedente alla pittura, sia quello successivo e finale. Anche nelle progettazioni in digitale, disegnare è sempre stato l’input di partenza. Inoltre, gran parte delle opere dei miei artisti preferiti in assoluto sono disegni.

Pd’A: Lavori a un quadro alla volta o ne realizzi più di uno contemporaneamente?

DR:Tendenzialmente lavoro a diversi quadri contemporaneamente, direi in media 5-6 alla volta. Raramente supero quel numero, ho bisogno di concentrarmi su un corpo ristretto di lavori. È una scelta voluta. La lavorazione di un quadro influenza quella degli altri e mi piace l’idea di lavorare ad un’unica grande opera distribuita su più supporti.

Un’eccezione alla regola è quando sperimento, o cerco nuove strade. In quelle fasi lavoro praticamente su un unico quadro alla volta: ho bisogno di concentrarmi su un singolo episodio, se poi il risultato non mi soddisfa passo direttamente al successivo.

Pd’A: Quando prepari una mostra o allestisci un’opera, sei interessato alla messa in scena?

DR: L’allestimento è un punto essenziale nel momento in cui penso ad una mostra. Ultimamente sono interessato all’idea di quadreria, è per me una modalità di mettere insieme opere diverse e di creare una connessione tra le stesse attraverso un elemento narrativo e cromatico. Ad esempio, ho realizzato in questa maniera l’allestimento nella mia ultima personale da Renata Fabbri, Quel pazzo di Paolo Uccello.

Pd’A: Secondo te il sacro ha ancora un’importanza nell’arte di oggi?

DR: Sicuramente è un elemento importante, ma sono ovviamente cambiate le dinamiche rispetto a secoli fa. L’arte non è più al servizio della sacralità e della religione, e questo è qualcosa che è accaduto probabilmente all’inizio del secolo scorso, almeno in Europa. È vero invece il contrario, ovvero che la sacralità viene spesso inserita ed utilizzata nell’arte contemporanea quale strumento di potenziamento, forse per elevare la portata del messaggio o la natura del progetto.

Questo, secondo me, presenta dei limiti: da un lato è evidente che ci sia una forzatura, e che la dimensione del sacro sia spesso fuori luogo nella contemporaneità. Dall’altro lato è un bene che la sacralità sia stata sdoganata, e che venga spesso inserita senza un diretto collegamento alla religione nelle riflessioni sul contemporaneo. Lo noto molto in opere che tendono al surrealismo, o ad un nuovo realismo magico. Molti miei dipinti hanno questi stessi riferimenti, soprattutto gli ultimi dove ho cercato di attuare una riflessione sulla morte senza cercare a tutti i costi l’elemento religioso.

Pd’A: Quale è la tua idea di bellezza?

DR: Si avvicina a due concetti: quello dell’inutilità, e quello dell’imprevisto.

Mi piace pensare che l’elemento essenziale di quello che per me può definirsi bello sia la completa inutilità, dal punto di vista pratico-funzionale e produttivo, di un’operazione: la bellezza emerge quando l’azione è completamente avulsa da qualsivoglia esigenza materiale. Realizzare azioni inutili non è ovviamente la garanzia del bello, ma credo sia un requisito imprescindibile. Da tante azioni inutili può nascere bellezza, forse anche perché, se si sottende uno scopo ben preciso – che può essere ad esempio l’esigenza di produrre nuove opere per una mostra imminente – la pressione che ne consegue a volte riduce la creatività.

L’imprevisto è diretta conseguenza di ciò: l’assenza di uno scopo e la possibilità, ad esempio, di inserire un elemento dissonante in una composizione potrebbe – al momento giusto – comportare l’aumento di quello che chiamiamo bellezza, o un suo salto di qualità.

È questo anche il motivo per cui non si può quantificare il tempo utile a realizzare un’opera di valore: settimane o mesi di sessioni possono non essere sufficienti a competere con un’unica giornata in cui questa libertà prende il sopravvento.

Pd’A: Le opere d’arte esistono se non c’è nessuno che le guarda?

DR: Questa domanda mi viene in mente in periodi nei quali temo una carenza di attenzione nei confronti del mio lavoro. Giungo alla conclusione che probabilmente non dipingerei più, se non avessi degli osservatori.

Ma pensandoci in maniera approfondita non credo che questo sia vero, presumo sia più una proiezione delle mie insicurezze: è più piacevole pensare di dipingere per un motivo, per un atto che volge ad una comunicazione, piuttosto che realizzare che questo avviene semplicemente per un’esigenza, quasi fisica, che si presenterebbe comunque.

Le opere d’arte esisterebbero comunque, perché il primo pensiero che muove un segno è dettato dal semplice gusto o istinto di farlo, come quando si è bambini.

Pd’A: Qual è la tua posizione rispetto al tuo lavoro?

DR: Ho sempre creduto nel mio lavoro, ma dovrei forse definire cosa significa credere in quello che faccio.

Ho sempre avuto la sensazione che nei miei lavori ci sia qualcosa avvicinabile al concetto di passione, che riesco a trasmettere nelle mie opere; quindi, sin dall’inizio ho sempre dato un valore importante a quello che realizzavo.

Ma non da molto tempo ho capito che questa passione non è cieca, non è un intenso sfogo emotivo che sfocia in un oggetto fisico. Ho realizzato che questa urgenza comunicativa non solo può essere veicolata in un messaggio comprensibile ad un soggetto diverso dall’autore, ma che il messaggio è sempre unito all’azione e che, se in passato non mi sono reso conto di ciò, è stato semplicemente per l’incapacità di decodificare la mia urgenza di comunicare.

Ora posso dire che la mia posizione nei confronti del mio lavoro è di rispetto: so che la mia ricerca ha un significato profondo per me, è la mia interpretazione della vita e fondamentalmente il mio modo di esorcizzare la morte. Credo che una delle meraviglie dell’esistenza sia proprio la capacità di produrre bellezza dal male e dai drammi, quindi il sublimare.

Domenico Ruccia (Bari, 1986) vive e lavora a Milano. Completati gli studi giuridici si dedica

completamente alla ricerca artistica, frequentando l’Accademia di Belle Arti di belle arti di

Brera, dove conclude gli studi in pittura nel 2021.

Tra le mostre personali ricordiamo quelle presso la Fondazione Mario Moderni (Roma 2017),

Chiostro del Bramante (Roma 2018), Il Crepaccio (Milano 2021), Collezione Pallavicini (Pavia

2023), Iperstudio (Viareggio 2023) e Galleria Renata Fabbri (Milano 2024).

Il suo lavoro è stato esposto anche in istituzioni pubbliche e private come Galleria Lorenzelli

(Milano 2017), Museo d’Arte Grafica Marchionni (Cagliari 2017), ArtDate (Bergamo 2021),

co_atto (Milano 2022), YAG/garage (Pescara 2023), Galleria Arrivada (Milano 2023),

Osservatorio Futura (Torino 2023), Galleria Civica Albani (Urbino 2023), Museo Civico di

Asiago (2024) e Galleria Alessandro Albanese (Matera 2024).

È tra gli artisti presenti nella mappatura Panorama della Quadriennale di Roma, con uno

studio visit di Lorenzo Madaro.

Nel 2022 è stato in residenza presso VIR Viafarini-in-residence di Milano.

English text

Interview to Domenico Ruccia

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #domenicoruccia

Parola d’Artista: For most artists, childhood is the golden age when the first symptoms of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Domenico Ruccia: From an early age, drawing was one of my main interests. It was my favourite activity over video games and cartoons, and often over friends and schoolmates. I liked and still like being alone, and drawing combined this tendency of mine. Over the years this has remained more or less unchanged.

Pd’A: Did you, like many others, have an artistic first love?

DR: If by artistic love you mean falling in love with an image, I am thinking mainly of record covers. I started looking at them as a child, going through my parents’ albums, and poking around inside CD booklets or vinyl packaging. The first artistic love in terms of songwriting was consequently the bands, I would say Queen in particular. There is this collection of theirs from 1991, Greatest Hits II, where on the cover there is a drawing stylising the zodiac signs of the band members. I learned of the meaning of the composition years later, but I immediately felt the power of a sign to encapsulate an underlying meaning.

Pd’A: What studies did you do?

DR: After finishing high school, I enrolled in law school. After graduating in Law and qualifying as a lawyer, I radically changed direction and dedicated myself to painting. Of course it was not a sudden decision, I always continued to draw, but I realised then that I only wanted to do that in life and I took a risk.

Pd’A: Were there any important encounters during your training years?

DR:After qualifying, I enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts, first in Bari for the three-year course, then in Brera in 2018 for the two-year specialisation course, I was very keen on it. During these years I had some important encounters. I could perhaps sum them up in my first maestro, a special person and artist to whom I am still attached and who made me realise I had potential, and then in some artists and professors I met at Brera, who helped me structure my work and create my own rules.

Pd’A: Where do the images you paint come from?

DR: My atlas has changed over time. When I focused on the world of entertainment in the 70s and 80s, the archive incorporated many images of music, film and fashion from those years, prompting me to search for vintage magazines, specialised archives and websites from which I mainly drew vintage rarities, which was what fascinated me the most.

Later, I started to select frames from some vintage films and commercials, which partly merged into my video series Spiritus mundi. These images were then superimposed on others, also in the archive, and I created stories from these strange collages.

The same operation was then carried out when I started working on Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes series: I created an archive section with images and details of late Gothic/Renaissance works, to which other collections on Chinese and Japanese graphics and painting of the 15th-16th centuries were added. The combination of these categories allowed me to create new collages, which then became the stories to be told in the new series.

Pd’A: What fascinates you about Paolo Uccello and art history in general?

DR: I am fascinated by the course of art history and its evolution in relation to the historical and political periods of a certain era. It is a theme that greatly influences the way I work, because I like to reinterpret a past context by inserting fictitious narratives that are functional to my storytelling. It is a process I have always used. Paolo Uccello is so fascinating because he represented perhaps like no other the temperature and the avant-garde of his era, but at the same time, many centuries later, he still manages to enter powerfully into the contemporary and be a paradigm for the future.

That is why reinterpreting his story is not a celebration of the past, but my way of having a sideways eye on the contemporary.

Pd’A: Are you interested in the idea of storytelling?

DR: It is essential to my work. I use painting as a tool to explore the concept of time and I like to invent untold stories, the fruit of my imagination, within historical contexts that really existed.

I always start from a datum belonging to the past, and from there I reconstruct everything with my imagination. The image becomes the tool to misinterpret history, to change it.

I have used this method both in my earlier works, which had the 70s and 80s as their focus, and in my more recent series, such as Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes. Here in particular, I imagined unpublished works by Paolo Uccello made during a fictitious trip to the Far East towards the end of his life, which the artist himself decided never to show. The irony of the narrative behind the project served me to tell something new. The series would not have made sense if there had not been a desire on my part to tell, even before the works, this journey through history.

Pd’A: I have seen that you also sometimes work with video by making looped images, what importance do the categories of time and space have for you?

DR: Video allowed me to work directly on the sources of the images I use in painting, i.e. films, advertisements, music videos, documentaries but also recordings made with a mobile phone. With Spiritus mundi, a series of videos I made between 2022 and 2023, I played with these sources as if they were collages, cutting them out, rearranging them and reinserting them in a non-logical but functional order for the work: they are a series of images without sound that alternate seamlessly on a FAN led installed on the wall. They represent an enhancement of my painting and an element to draw new inspiration, also because the support I used, a luminous fan, is as essential to the correct reproduction of the work as a canvas is to a painting.

Pd’A: How important is colour in your work?

DR: Colour is a tool to define the temperature of a painting, on the same level as the subject, the setting or the lines and shapes. Over the years, my palette has undergone many changes. In Piccole dissertazioni di stringente attualità the focus was on the 70s and 80s, a certain kind of modernity of which today we only have the nostalgic element, and the tones veered towards these bright, lacquered, often unfashionable colours. With Paolo Uccello’s Outtakes everything shifted to pastel, not only in relation to the representation of what I was painting, such as the trees and mountains, but because that palette was more functional for me in taking up epically, but also ironically, a discourse on the Renaissance. So I would say that the first function of colour is to contextualise and define the intent of a work.

Pd’A: What importance and role does drawing play in what you do?

DR: Many ideas I have had were born from drawing, or were conceived with it. There have been periods when painting only with paints and brushes took over, but it was temporary. Today, I see no difference, I use a graphic sign with crayons and pencils in my paintings and often the drawing is both the previous step to painting and the next and final step. Even in digital designs, drawing has always been the starting input. Also, most of my favourite artists’ works are drawings.

Pd’A: Do you work on one painting at a time or do you do more than one at the same time?

DR: I tend to work on several paintings at once, I would say on average 5-6 at a time. I rarely exceed that number, I need to concentrate on a smaller body of work. It is a deliberate choice. The work on one painting influences that of the others and I like the idea of working on one large work spread over several media. An exception to the rule is when I experiment, or look for new ways. In those phases I work on practically one painting at a time: I need to concentrate on a single episode, and if I am not satisfied with the result then I go straight to the next one.

Pd’A: When you prepare an exhibition or set up a work, are you interested in staging?

DR: Staging is an essential point when I think about an exhibition. Lately I have been interested in the idea of a picture gallery, it is for me a way of putting different works together and creating a connection between them through a narrative and chromatic element. For example, I created the set-up in this way in my last solo exhibition at Renata Fabbri, Quel pazzo di Paolo Uccello.

Pd’A: Do you think the sacred still has an importance in art today?

DR: Certainly it is an important element, but the dynamics have obviously changed compared to centuries ago. Art is no longer at the service of sacredness and religion, and this is something that probably happened at the beginning of the last century, at least in Europe. Instead, the opposite is true, namely that sacredness is often included and used in contemporary art as an empowering tool, perhaps to elevate the scope of the message or the nature of the project. This, in my opinion, has its limits: on the one hand, it is evident that there is a forcing, and that the dimension of the sacred is often out of place in the contemporary. On the other hand, it is good that sacredness has been cleared through customs, and is often included without a direct connection to religion in reflections on the contemporary. I notice this a lot in works that tend towards surrealism, or a new magic realism. Many of my paintings have these same references, especially the latest ones where I have tried to implement a reflection on death without seeking the religious element at all costs.

Pd’A: What is your idea of beauty?

DR: It comes close to two concepts: that of futility, and that of the unexpected.

I like to think that the essential element of what for me can be defined as beauty is the complete uselessness, from a practical-functional and productive point of view, of an operation: beauty emerges when the action is completely divorced from any material need. Performing useless actions is obviously not a guarantee of beauty, but I believe it is an essential requirement. Beauty can be born from many useless actions, perhaps also because, if there is a clear purpose behind it – which can be, for example, the need to produce new works for an upcoming exhibition – the resulting pressure sometimes reduces creativity.

The unexpected is a direct consequence of this: the absence of a purpose and the possibility, for example, of inserting a dissonant element into a composition could – at the right moment – lead to an increase in what we call beauty, or a leap in its quality.

This is also the reason why one cannot quantify the time needed to create a valuable work: weeks or months of sessions may not be enough to compete with a single day when this freedom takes over.

Pd’A: Do works of art exist if there is no one to look at them?

DR: This question comes to mind at times when I fear a lack of attention towards my work. I come to the conclusion that I probably wouldn’t paint any more if I didn’t have viewers.

But thinking about it in depth, I don’t think this is true, I assume it is more a projection of my own insecurities: it is more pleasant to think that I paint for a reason, for an act that aims at a communication, rather than realising that this is simply because of a need, almost physical, that would arise anyway.

Works of art would exist anyway, because the first thought that moves a sign is dictated by the simple taste or instinct to do so, like when you are a child.

Pd’A: What is your position regarding your work?

DR: I have always believed in my work, but I should perhaps define what it means to believe in what I do.

I have always had the feeling that in my work there is something approaching the concept of passion, which I am able to convey in my work; therefore, from the beginning I have always placed an important value on what I make.

But not long ago I realised that this passion is not blind, that it is not an intense emotional outburst that results in a physical object. I realised that this communicative urgency can not only be conveyed in a message that is comprehensible to a subject other than the author, but that the message is always united with the action, and that if I did not realise this in the past, it was simply due to an inability to decode my urgency to communicate.

I can now say that my position towards my work is one of respect: I know that my research has a deep meaning for me, it is my interpretation of life and fundamentally my way of exorcising death. I believe that one of the wonders of existence is precisely the ability to produce beauty out of evil and drama, hence the sublimation.

Domenico Ruccia (Bari, 1986) lives and works in Milan. After completing his legal studies he dedicated himself completely to artistic research, attending the Academy of Fine Arts in Brera, where he completed his studies in painting in 2021.

Solo exhibitions include those at the Fondazione Mario Moderni (Rome 2017), Chiostro del Bramante (Rome 2018), Il Crepaccio (Milan 2021), Collezione Pallavicini (Pavia 2023), Iperstudio (Viareggio 2023) and Galleria Renata Fabbri (Milan 2024).

His work has also been exhibited in public and private institutions such as Galleria Lorenzelli (Milan 2017), Museo d’Arte Grafica Marchionni (Cagliari 2017), ArtDate (Bergamo 2021), co_atto (Milan 2022), YAG/garage (Pescara 2023), Galleria Arrivada (Milan 2023), Osservatorio Futura (Turin 2023), Galleria Civica Albani (Urbino 2023), Museo Civico di Asiago (2024) and Galleria Alessandro Albanese (Matera 2024).

He is among the artists featured in the Panorama mapping of the Quadriennale di Roma, with a studio visit by Lorenzo Madaro.

In 2022 he was in residence at VIR Viafarini-in-residence in Milan.