(▼Scroll down for English version)

#paroladartista #sacro #sacred #carolaallemandi

Parola d’Artista: Secondo te il sacro ha ancora una sua importanza nell’arte di oggi e nel mondo in cui viviamo?

Carola Allemandi: Parlare della rappresentazione del sacro, oggi, sembra sollevare scarsissimo interesse: il limite dell’indicibile è stato riportato entro i confini delle cose e degli eventi del mondo, e, quindi, alla sola opera dell’uomo.

La questione legata all’arte sacra contemporanea era già stata sollevata nel 2013 da Gillo Dorfles, che sul Corriere della Sera aprì un dibattito attorno al tema “Religione e modernità. L’arte sacra contemporanea? Che orrore” basato su due domande dirette e cardinali: “E’ sufficiente la fede per far accettare la mediocrità di tanta arte contemporanea? E, d’altra parte, è possibile un’arte veramente attuale che sia anche sacra?” Questo mi ha fatto capire quanto l’arte contemporanea abbia operato una cesura netta con la storia dell’arte e la sua tradizione iconografica, marginalizzando e curando poco tutto ciò che possa derivare dal sapere legato al sacro, o più nello specifico alla religione.

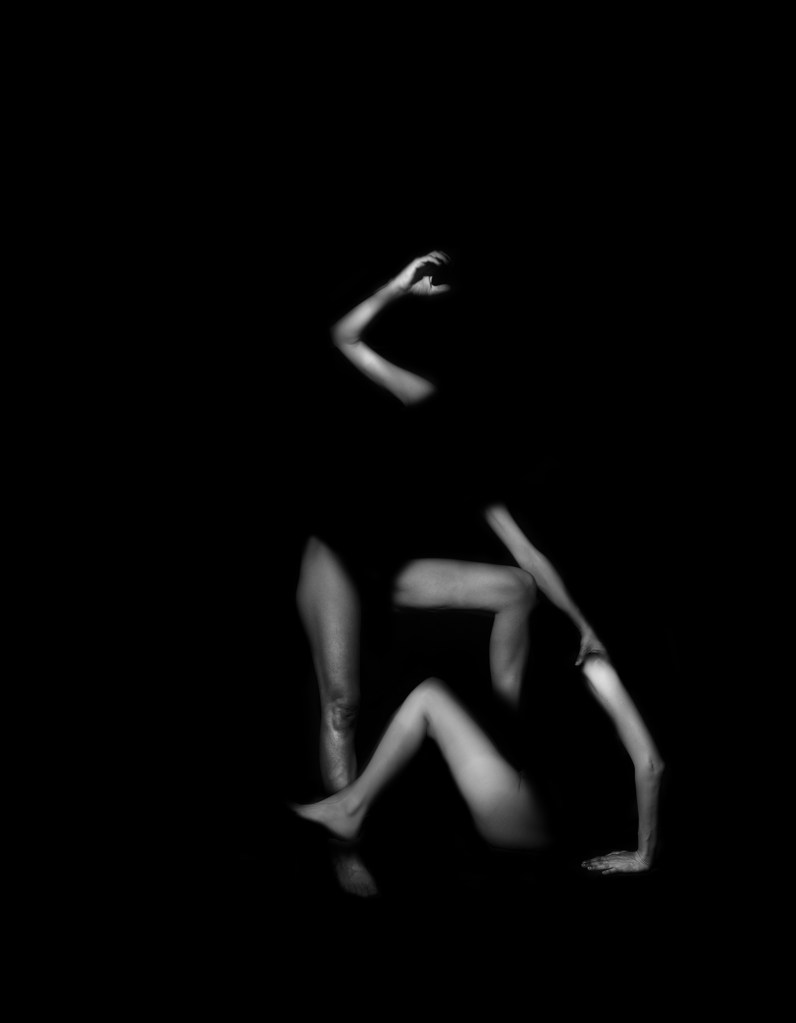

Io stessa, nell’affrontare l’argomento biblico nei miei ultimi lavori, so che potrei sollevare dello scetticismo, soprattutto col tentativo di inserire e comunicare questi soggetti all’interno della struttura fotografica, che ha visto pochi tentativi in questa direzione. Ma è uno studio che a mio avviso va tentato assolutamente.

Per rispondere, quindi, alla tua domanda: il tema del sacro avrebbe o dovrebbe avere una sua importanza nell’arte e nella vita di oggi, che di fatto non gli viene concessa spesso. Leggevo inoltre, a questo proposito, in un articolo uscito su Doppiozero un paio di anni fa (https://www.doppiozero.com/lo-strano-posto-della-religione-nellarte-contemporanea) di Michela Dall’Aglio, che James Elkins, storico e critico dell’arte e autore di cui Dall’Aglio analizza il saggio “Lo strano posto della religione nell’arte contemporanea” avrebbe “cominciato a interessarsi al rapporto tra arte contemporanea e religione dopo essersi reso conto che, tra gli studenti che frequentavano i suoi corsi, i pochissimi intenzionati a realizzare opere di carattere religioso non trovavano attenzione da parte degli insegnanti, perciò lasciavano perdere, o tenevano per sé il loro interesse.” Questo mi ha fatto pensare che, chissà, forse oggi esisterebbe una florida scuola di pensiero attorno all’arte sacra contemporanea, messa semplicemente a tacere o ignorata da un sistema (critico e accademico) che ha voluto escludere dal proprio dettato questo tema.

E’ chiaro, d’altronde, che l’uomo moderno abbia dovuto liberarsi dal fardello che il sistema religioso – la sua emanazione terrena, ecclesiastica – per secoli ha imposto sulle coscienze degli uomini. E dunque, quando Nietzsche esclamava nel 1882 che “il mare non è mai stato così aperto” dopo aver postulato la sua nota “morte di Dio” possiamo immaginare che sì, fosse un salto necessario da compiere. Il problema, a mio avviso, è l’aver stigmatizzato tutto ciò che è esistito prima di quel salto, non provando a salvare più nulla, o quasi, di ciò che lo precedeva, perdendo di fatto un legame con la storia del pensiero e del sentimento dell’uomo.

Questo, allora, potrebbe essere un nuovo tema di riflessione: cosa, e quanto, di quel pensiero e di quel sentimento può essere salvato e cosa, e quanto, quel pensiero e quel sentimento possono ancora dirci.

English text

On sacred Carola Allemandi

#paroladartista #sacro #sacred #carolaallemandi

Parola d’Artista: In your opinion, does the sacred still have an importance in art today and in the world we live in?

Carola Allemandi: Talking about the representation of the sacred, today, seems to arouse very little interest: the limit of the unspeakable has been brought back within the confines of things and events in the world, and, therefore, to the work of man alone.

The question of contemporary sacred art had already been raised in 2013 by Gillo Dorfles, who opened a debate in Corriere della Sera on the theme “Religion and modernity. Contemporary sacred art? Che orrore” based on two direct and cardinal questions: “Is faith enough to make people accept the mediocrity of so much contemporary art? And, on the other hand, is a truly contemporary art that is also sacred possible?” This made me realise how much contemporary art has made a clean break with the history of art and its iconographic tradition, marginalising and paying little attention to anything that might derive from knowledge related to the sacred, or more specifically to religion.

I myself, in tackling the biblical subject in my latest works, know that I could raise some scepticism, especially with the attempt to insert and communicate these subjects within the photographic structure, which has seen few attempts in this direction. But it is a study that in my opinion should definitely be attempted.

To answer, therefore, your question: the theme of the sacred would or should have its own importance in today’s art and life, which in fact is not often granted to it. I also read, in this regard, in an article published in Doppiozero a couple of years ago (https://www.doppiozero. com/lo-strano-posto-della-religione-nell’arte-contemporanea) by Michela Dall’Aglio, that James Elkins, art historian and critic and author whose essay “The Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art” Dall’Aglio analyses, is said to have “begun to take an interest in the relationship between contemporary art and religion after realising that, among the students who attended his courses, the very few who wanted to create works of a religious nature did not find attention from the teachers, so they left it alone, or kept their interest to themselves. This made me think that, who knows, perhaps today there would exist a flourishing school of thought around contemporary sacred art, simply silenced or ignored by a system (critical and academic) that has wanted to exclude this subject from its own dictate.

It is clear, moreover, that modern man has had to free himself from the burden that the religious system – its earthly, ecclesiastical emanation – has imposed on men’s consciences for centuries. And so, when Nietzsche exclaimed in 1882 that ‘the sea has never been so open’ after postulating his well-known ‘death of God’, we can imagine that yes, it was a necessary leap to take. The problem, as I see it, is the stigmatisation of everything that existed before that leap, trying to save nothing, or almost nothing, of what preceded it, effectively losing a link with the history of human thought and feeling.

This, then, could be a new theme for reflection: what, and how much, of that thought and feeling can be saved and what, and how much, that thought and feeling can still tell us.

Deposizione

Caino e Abele

Pietà

Ecce Homo

Giacobbe e l’angelo

PH Davies Zanbotti