(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #federicogiannini #verofalsofake #intervistacritico #criticinterview

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Federico, di che cosa parli nel libro Vero Falso Fake?

Federico Giannini : Di tutto quello che solitamente etichettiamo con l’espressione “fake news”, nonostante non sia il termine più corretto. Io preferisco parlare di “disordine informativo”, ovvero l’insieme di tutti i fenomeni che producono distorsioni nel mondo dell’informazione: quindi non soltanto la disinformazione, e quindi le notizie fabbricate appositamente per danneggiare qualcuno o qualcosa, ma anche tutte quelle distorsioni più sfumate e forse anche meno facili da distinguere, dalle notizie date fuori contesto a quelle sensazionalistiche, dai contenuti manipolati alle alterazioni più o meno evidenti. E poiché l’arte non è un settore esente dal problema del disordine informativo, non lo è mai stato (come penso qualsiasi altro settore), ho deciso di parlare di disordine informativo attraverso l’arte, partendo dal Quattrocento (perché non parliamo di un problema nuovo: parliamo di un problema che, forse, nasce quando l’essere umano s’è accorto che poteva comunicare con un suo simile), fino ad arrivare a oggi. L’arte, insomma, è una sorta di splendido pretesto per parlare d’attualità, dacché il disordine informativo è un disturbo dell’informazione con cui tutti i giorni abbiamo a che fare.

Pd’A: Quello delle fake news è un argomento molto in voga, in che modo hai affrontato l’argomento?

F.G.: Intanto cercando dei casi, degli episodi della storia dell’arte attraverso cui esplorare delle dinamiche che si manifestano senza grosse modifiche nell’attualità e anche in settori che niente hanno a che vedere con l’arte: credo che gli schemi del disordine informativo si possano applicare senza differenze sostanziali a qualunque argomento possa essere oggetto d’informazione. E poi analizzando alcune delle cosiddette “bufale”, ovvero gli oggetti del disordine informativo, alcune delle quali talmente suggestive da esser diventato mito creduto realtà (penso alla “Gioconda rubata da Napoleone”, su cui tuttavia tanti ormai sono ben informati, anche se è un argomento che tocca ancora molti nel profondo, ma anche alla “Simonetta Vespucci musa di Botticelli” e ad altre), e altre invece al centro di casi giornalistici recenti. L’arte, dicevo, non è immune dal problema e, anzi, forse è ancora più esposta rispetto ad altri settori per il fatto che nelle redazioni culturali di molte testate generaliste spesso mancano esperti o figure in grado di valutare in maniera critica tutto quello che arriva in redazione, con la conseguenza che spesso i filtri sono più larghi e non di rado notizie destituite di qualunque fondamento (penso per esempio a mirabolanti ritrovamenti in cantina o in soffitta, oppure a ignobili croste spacciate per capolavori da sedicenti esperti) riescono ad arrivare ai destinatari. E anche se ormai, nel mondo dell’informazione italiano, l’arte e la storia dell’arte probabilmente sono considerate argomenti di serie C se non anche inferiori, non si possono sottostimare i danni provocati da un bufala fatta trapelare per scarsa conoscenza dell’argomento, perché non si sono sentiti gli esperti, perché le verifiche sono state blande (se ci sono state e non ci si è limitati a risciacquare un comunicato stampa): il fatto è che anche bufale che riteniamo di poco conto sono nocive. Quale danno procurerà mai, potremmo pensare, la falsa notizia, nata da un equivoco, da un’incomprensione (ne parlo nel libro), del ritrovamento, all’Archivio di Stato di Spezia, dell’originale della Pace di Dante, ovvero un documento che in realtà conosciamo da più di cent’anni. Un argomento che interessa, potremmo pensare, giusto gli studiosi, gli appassionati di storia, la comunità locale. Il fatto è che, intanto, non si può stabilire a priori la risonanza che avrà una notizia: spesso notizie apparentemente di poco conto diventano cronaca nazionale. Tornando però al punto, il fatto è che anche una bufala ritenuta lieve può provocare danni: oltre, naturalmente, a trasmettere informazioni errate (e quindi a generare percezioni distorte) e a esporsi al rischio di diffusione incontrollata, contribuisce a minare la fiducia nella stampa e di conseguenza alimentare lo scetticismo, a creare assuefazione alla falsità, ad arare il terreno di coltura della pseudoscienza, a confondere il pubblico, a rinforzare pregiudizi.

Pd’A: Le notizie false e le bufale accompagnano da sempre la storia dell’arte e talvolta la influenzano profondamente ci sono svariati esempi come quello del processo a Paolo Veronese da parte della Santa Inquisizione una bufala settecentesca in cui sono caduti praticamente tutti i maggiori storici dell’arte oppure il caso di padre Athanasius Kircher gesuita, erudito, collezionista di cose meravigliose, la cui raccolta ha dato vita ad un importante museo a Roma nel 1600, non che fabbricatore di notizie false come quella riguardante la scoperta da parte sua della decodifica dei Geroglifici Egiziani che porto a stabilire l’iconografia su cui Bernini ha realizzato la fontana dei 4 Fiumi in Piazza Navona. Nel libro su che casi ti sei soffermato?

F.G.: Dovendo contenere tutto in poco più di duecento pagine, purtroppo non mi sono potuto concentrare su tutto quello che avrei voluto. Per esempio ho lasciato fuori dalla trattazione tutti quei casi recenti di attribuzioni errate, sensazionalistiche (i vari “capolavori” di Caravaggio, Leonardo, Raffaello e compagnia che spesso vengono rilanciati anche dalla stampa autorevole: non li ho affrontati perché sono materia di stretta attualità e poi perché casi così eclatanti solitamente vengono smentiti nel giro di poche ore… noi su Finestre sull’Arte dedichiamo molta attenzione a questi casi e quindi sulla nostra rivista si trova già una trattazione piuttosto ampia su questi argomenti), e mi sono invece concentrato o su casi storici, oppure su casi più recenti che però hanno avuto forte risonanza e hanno acceso il dibattito scientifico. Ho cercato di fare una cernita che coprisse il più ampio spettro di dinamiche di creazione e diffusione delle notizie false o distorte: la selezione ha tenuto conto anche di questo aspetto, perché ognuno dei capitoli del libro presenta un caso paradigmatico di un certo motivo per cui si diffonde un’informazione falsa o di una dinamica che porta alla sua diffusione. E ho poi cercato di bilanciare casi noti con casi meno noti. Qualche esempio: la bufala dell’Italia che detiene il 60% del patrimonio artistico mondiale e la summenzionata Simonetta Vespucci musa di Botticelli per citare un paio di miti duri a morire, e poi alcuni casi meno noti come il mito del bronzo del Pantheon fuso per il Baldacchino del Bernini (nel libro, rifacendomi a uno studio recente di Louise Rice, spiego che in realtà questa convinzione, nella quale abbiamo sempre creduto, è in realtà destituita di fondamento perché frutto della propaganda di Urbano VIII), o come il caso dei falsi di Annio da Viterbo, un umanista vissuto nel XV secolo e che possiamo considerare una sorta di pioniere della disinformazione, anche di quella odierna, perché alcuni dei meccanismi che Annio da Viterbo mise in pratica per rendere credibili le sue falsificazioni sono ancora attuali.

Pd’A: Viviamo nell’era della Post Verità come tutto questo si ripercuote nell’arte dei nostri giorni?

F.G.: Per “post-verità” intendiamo un’argomentazione basata su credenze diffuse e fatti non verificati che tengono però a essere accettati come veritieri e che di solito fa appello all’emotività collettiva. Penso che il concetto stesso di “significato” abbia conosciuto qualche cambiamento in questa nostra era della post-verità (e va detto che, anche se forse non è più molto di moda parlarne, ci siamo ancora dentro: basta aprire un social a caso per rendersene conto, anche perché credo sia incontestabile che i social abbiano contribuito al dilagare della disinformazione e, per come sono oggi, siano il brodo di coltura ideale per la post-verità), e tutto questo nell’arte si ripercuote essenzialmente in due modi: le opere che commentano quello che accade (e che a mio avviso sono anche quelle meno interessanti) e quelle che invece cercano, da una parte, di ragionare sui meccanismi che regolano questa nostra epoca, e dall’altra di offrircene una sorta di rappresentazione sublimata, di farci vedere in un lampo quello che sta accadendo. Nel libro mi soffermo su due esempi, uno, chiamiamolo così, di “disvelamento”, e l’altro di “rappresentazione”, ovvero This is the future di Hito Steyerl e Facebook di George Condo, entrambi esposti alla Biennale di Venezia del 2019, quella di Ralph Rugoff, che affrontava il tema della post-verità. Nel libro faccio anche altri esempi, ma questi due sono quelli che esamino in maniera un poco più approfondita. Il problema, credo, è che l’arte contemporanea oggi fatica a far emergere discussioni pubbliche significative (e non solo in tema di post-verità), per il fatto che l’arte oggi appare lontana dalle preoccupazioni delle persone. E spesso l’arte contemporanea è ritenuta difficile, poco comprensibile. L’antidoto, probabilmente, potrebbe consistere nel creare una forma d’arte che diventi nuova narrazione, che magari fondi il suo approccio sulla connessione tra le persone evitando d’imporre e che affronti problemi tangibili, concreti, che non rimanga sull’astratto. Ma è molto difficile, l’unico che forse di recente ha ottenuto qualche risultato in questo senso ritengo sia stato Arthur Jafa.

Pd’A: In un epoca in cui chiunque può, tramite l’I.A. e i social, inventare e/o diffondere notizie false fino a farle diventare “virali” come ci si può difendere?

F.G.: Non è facile, anche perché le bufale hanno un vantaggio sulla verità: sono estremamente più veloci. Prima che arrivi una smentita, la bufala avrà già fatto in tempo a compiere il giro del mondo. Di solito faccio l’esempio dell’antivirus del computer: l’ultimo antivirus, anche il più potente e il più sicuro, sarà sempre meno aggiornato rispetto all’ultimo virus. Il debunking (l’attività giornalistica di demistificazione delle bufale) è fondamentalmente uno strumento di cura, ovviamente importante, ma non può essere la soluzione, anche perché talvolta, se fatto (come va di moda adesso) con toni aggressivi, specie sui social, rischia addirittura di aggravare il problema, perché diventa un’attività polarizzante. E poi, le bufale esisteranno sempre. Nel capitolo finale del libro propongo una strategia, che riassumo qui in breve: accettare l’idea che il disordine informativo esisterà sempre, mettere in atto le buone pratiche suggerite dagli esperti (ne cito alcune: diffidare dei titoli sensazionalistici o allarmistici, diffidare dei contenuti che vengono presentati solo per spingere a una presa di posizione, verificare se le fonti citate da un autore effettivamente riportano quanto detto, diffidare delle notizie accompagnate da call to action come “condividi se sei indignato” o simili, anche in forme più larvate, condividere un contenuto sui social soltanto se si è sicuri di aver verificato che è affidabile, e se si ha un dubbio chiedere a un esperto oppure consultare testate serie o profili social di giornalisti ed esperti noti per la loro affidabilità), cercare di capire come nascono e come si diffondono le bufale, essere consapevoli del fatto che è fisicamente impossibile vagliare qualunque notizia a verifica e quindi mettersi in una posizione di vigilanza, sapendo che tra la supina accettazione di qualunque cosa ci venga propinata e lo scetticismo su tutto esistono molte sfumature.

English text

Interview to Federico Giannini on his book “Vero Falso Fake edited by Giunti

#paroladartista #federicogiannini #verofalsofake #intervistacritico #criticinterview

Parola d’Artista: Hello Federico, what is your book Vero Falso Fake? about?

Federico Giannini: It’s about everything we usually label as “fake news,” even though that’s not the most accurate term. I prefer to talk about “information disorder,” which is the collection of all the phenomena that cause distortions in the world of information. So, it’s not just disinformation—that is, news fabricated specifically to harm someone or something—but also all those more nuanced and perhaps less obvious distortions, from news taken out of context to sensationalistic articles, from manipulated content to more or less obvious alterations.

Since art is not a sector exempt from the problem of information disorder—it never has been, just like any other sector—I decided to talk about information disorder through the lens of art, starting from the 15th century (because this isn’t a new problem; it’s a problem that perhaps began when humans realized they could communicate with each other) all the way to today. Art, in short, is a sort of wonderful excuse to talk about current events, as information disorder is an information-related issue we deal with every day.

Pd’A: The topic of fake news is very popular. How did you approach the subject?

F.G.: First, I looked for cases and episodes in art history to explore dynamics that manifest themselves in current events without major changes and also in fields that have nothing to do with art. I believe the patterns of information disorder can be applied without substantial differences to any subject that can be a source of information.

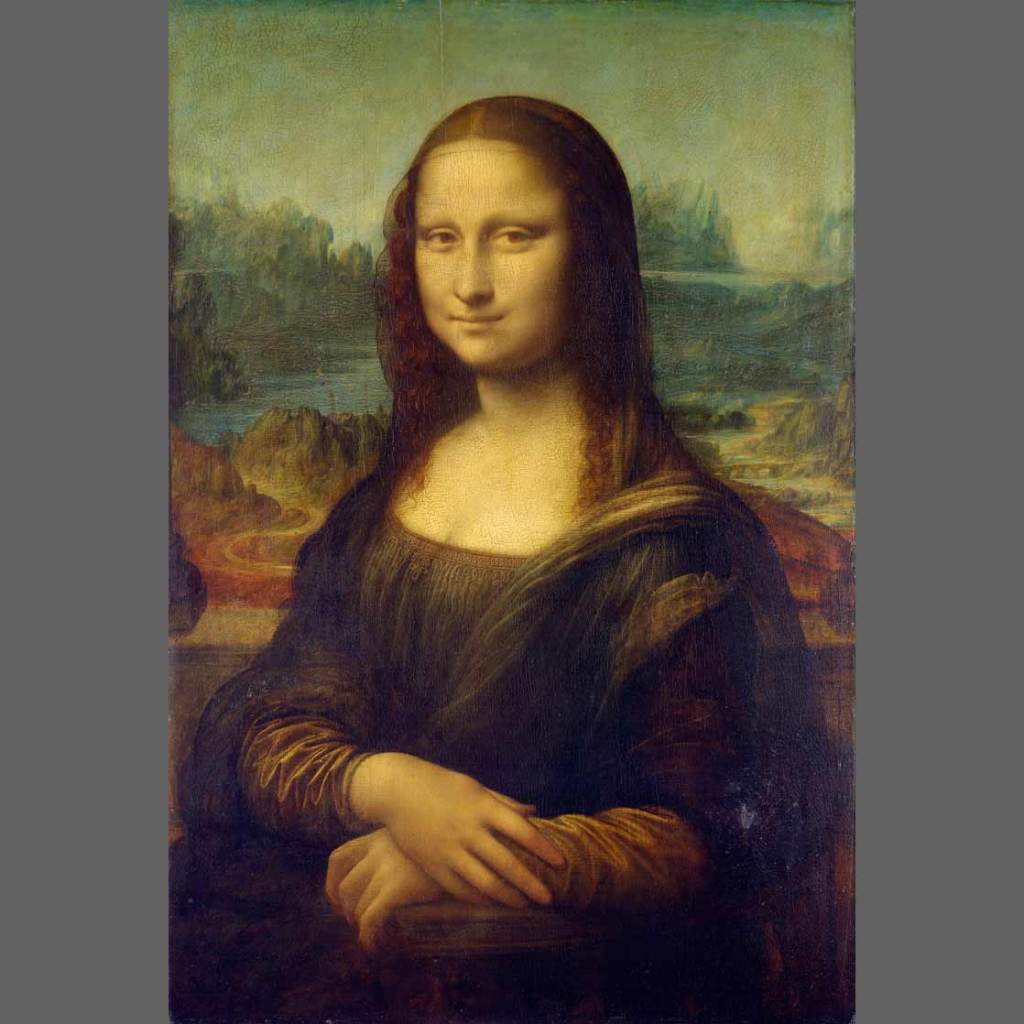

Then, I analyzed some of the so-called “hoaxes”—that is, the subjects of information disorder. Some are so captivating that they’ve become myths believed to be true (I’m thinking of “the Mona Lisa stolen by Napoleon,” which many people are now well-informed about, though it still deeply affects many, but also the “Simonetta Vespucci as Botticelli’s muse” and others). Other hoaxes have been at the center of recent journalistic cases.

Art, as I said, is not immune to this problem. In fact, it’s perhaps even more exposed than other sectors because the culture desks of many generalist newspapers often lack experts or figures who can critically evaluate everything that comes in. As a result, the filters are often wider, and it’s not uncommon for news without any foundation to reach recipients (I’m thinking, for example, of incredible findings in a basement or an attic, or disgraceful works passed off as masterpieces by self-proclaimed experts).

And even if art and art history are probably considered B-list, if not even lower, topics in the Italian media world, the damage caused by a hoax that is spread due to a poor understanding of the subject, or because experts weren’t consulted, or because verifications were weak (if they even happened at all and they didn’t just re-publish a press release) shouldn’t be underestimated. The fact is, even hoaxes we think are minor are harmful. What damage could the false news, born from a misunderstanding (which I talk about in the book), cause about the discovery of Dante’s Peace Treaty original at the Spezia State Archives, a document we’ve actually known about for over a hundred years? We might think it only interests scholars, history enthusiasts, and the local community. The fact is, you can’t determine in advance how much resonance a piece of news will have: news that seems minor often becomes national news. But going back to the point, even a seemingly minor hoax can cause damage. Besides, of course, transmitting incorrect information (and thus generating distorted perceptions) and risking uncontrolled spread, it also contributes to undermining trust in the press, thereby fueling skepticism, creating a tolerance for falsehoods, plowing the breeding ground for pseudoscience, confusing the public, and reinforcing prejudices.

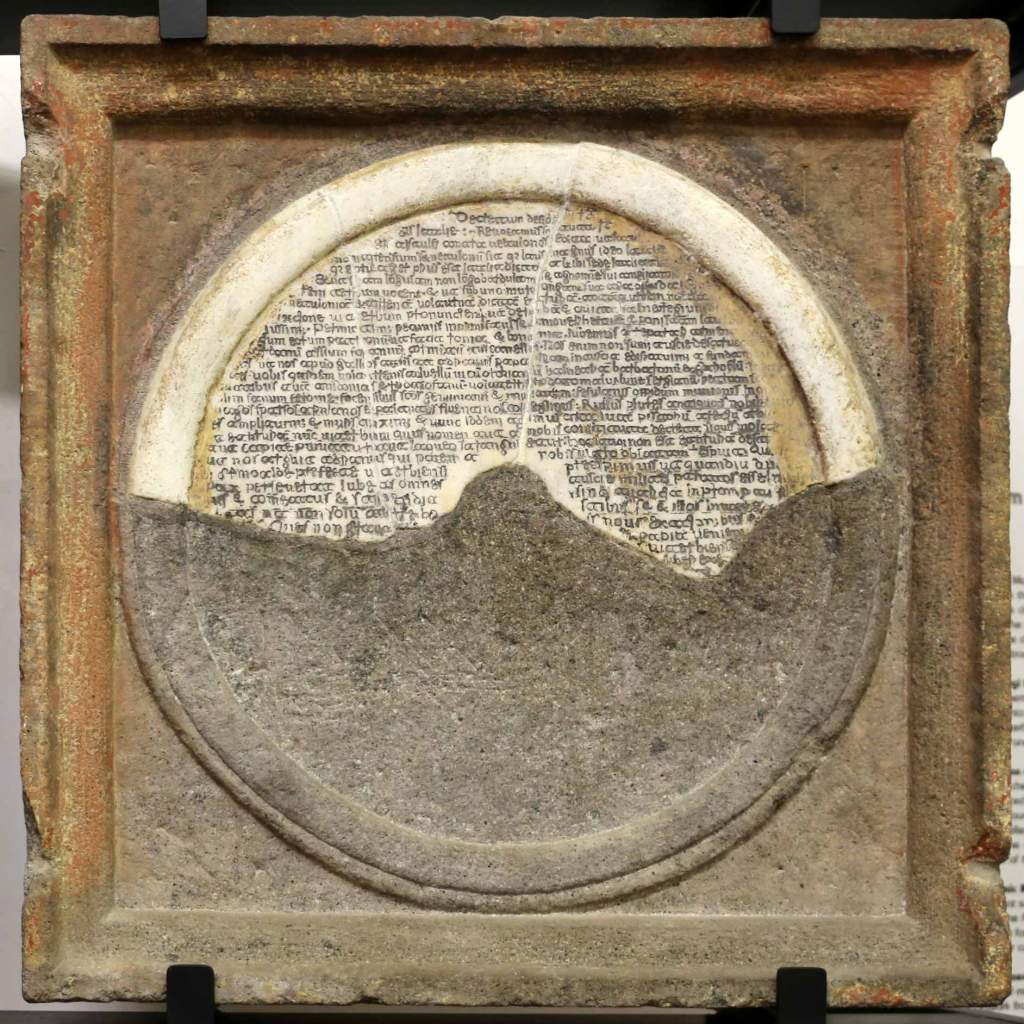

Pd’A: Fake news and hoaxes have always been a part of art history and sometimes deeply influence it. There are several examples, such as the trial of Paolo Veronese by the Holy Inquisition, an 18th-century hoax that almost all major art historians fell for, or the case of Father Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit, scholar, and collector of wonderful things whose collection gave rise to an important museum in Rome in the 1600s—not to mention a fabricator of false news, like his supposed discovery of how to decode Egyptian Hieroglyphics, which led to the iconography on which Bernini based the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona. Which cases did you focus on in your book?

F.G.: Since I had to keep everything to just over two hundred pages, unfortunately, I couldn’t focus on everything I wanted to. For example, I left out all the recent cases of incorrect, sensationalistic attributions (the various “masterpieces” by Caravaggio, Leonardo, Raphael, and others that are often re-shared even by authoritative newspapers: I didn’t address them because they are very current, and also because such blatant cases are usually debunked within a few hours… we pay a lot of attention to these cases at Finestre sull’Arte and so a rather extensive discussion on these topics can already be found in our magazine). Instead, I focused on either historical cases or more recent cases that had a strong resonance and sparked scientific debate.

I tried to make a selection that covered the broadest spectrum of the dynamics of creating and spreading false or distorted news. The selection also took this aspect into account, because each chapter of the book presents a paradigmatic case of a certain reason why false information spreads or a dynamic that leads to its dissemination. And I also tried to balance well-known cases with lesser-known ones.

A couple of examples: the hoax that Italy holds 60% of the world’s artistic heritage and the aforementioned Simonetta Vespucci as Botticelli’s muse, to cite a couple of stubborn myths. And then some lesser-known cases, like the myth of the bronze from the Pantheon being melted down for Bernini’s Baldacchino (in the book, drawing on a recent study by Louise Rice, I explain that this long-held belief is actually baseless because it was the result of Urban VIII’s propaganda). Or the case of the forgeries by Annio da Viterbo, a 15th-century humanist who can be considered a kind of pioneer of disinformation, even today’s, because some of the mechanisms Annio da Viterbo used to make his forgeries credible are still relevant today.

Pd’A: We live in the era of post-truth. How does all this affect the art of our time?

F.G.: By “post-truth,” we mean an argument based on widespread beliefs and unverified facts that are nevertheless accepted as true, and which usually appeals to collective emotion. I think the very concept of “meaning” has undergone some changes in our post-truth era (and it must be said that, even if it’s not so fashionable to talk about it anymore, we are still in it; you just have to open a random social network to realize it, also because I believe it’s undeniable that social media has contributed to the spread of disinformation and, as they are today, they are the ideal breeding ground for post-truth). And all this affects art in essentially two ways: works that comment on what is happening (which, in my opinion, are also the least interesting ones) and those that, on the one hand, try to reason about the mechanisms that regulate this era of ours, and on the other, offer us a kind of sublimated representation of it, to show us in a flash what is happening.

In the book, I focus on two examples, one of what we might call “unveiling” and the other of “representation”: Hito Steyerl’s This is the future and George Condo’s Facebook, both exhibited at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the one curated by Ralph Rugoff, which addressed the theme of post-truth. I also give other examples in the book, but these two are the ones I examine in a little more depth. The problem, I think, is that contemporary art today struggles to generate significant public discussion (and not just on the topic of post-truth) because art today seems distant from people’s concerns. And contemporary art is often considered difficult and not very understandable. The antidote, probably, could be to create an art form that becomes a new narrative, that perhaps bases its approach on connecting people by avoiding imposing anything, and that tackles tangible, concrete problems, that doesn’t remain abstract. But it’s very difficult; the only one who has perhaps recently achieved some results in this sense, I believe, is Arthur Jafa.

Pd’A: In an era where anyone can, through AI and social media, invent and/or spread fake news to the point of it becoming “viral,” how can we defend ourselves?

F.G.: It’s not easy, also because hoaxes have an advantage over the truth: they are extremely faster. Before a refutation arrives, the hoax will have already had time to travel around the world. I usually use the example of a computer’s antivirus: the latest antivirus, even the most powerful and secure, will always be less up-to-date than the latest virus. Debunking (the journalistic activity of demystifying hoaxes) is fundamentally a treatment tool, obviously important, but it cannot be the solution, also because sometimes, if done (as is fashionable now) with aggressive tones, especially on social media, it even risks worsening the problem, because it becomes a polarizing activity. And besides, hoaxes will always exist.

In the final chapter of the book, I propose a strategy, which I’ll summarize here briefly: accept the idea that information disorder will always exist; implement good practices suggested by experts (I mention some: be wary of sensationalistic or alarmist headlines; be wary of content presented only to push you to take a stance; check if the sources cited by an author actually report what they said; be wary of news accompanied by calls to action like “share if you are outraged” or similar, even in more subtle forms; only share content on social media if you are sure you have verified that it is reliable, and if you have a doubt, ask an expert or consult serious newspapers or social media profiles of journalists and experts known for their reliability); try to understand how hoaxes are born and how they spread; be aware that it is physically impossible to vet every piece of news for verification and therefore put yourself in a position of vigilance, knowing that there are many shades between the supine acceptance of anything we are fed and skepticism about everything.

Ph: Alessandro Pasquali / Danae Project