(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #artistinterview #intervistaartista #frankob

Pd’A: Ciao Franko, chi sono queste persone?

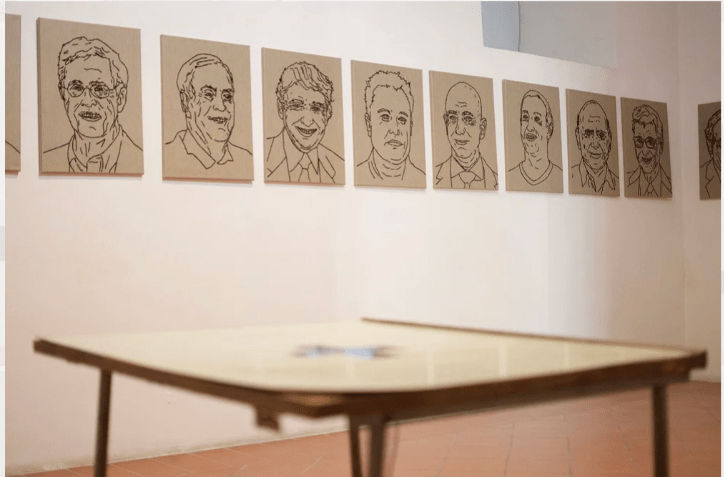

Franko B: Allora, questa serie è basata sull’ultima cena, sono in tutto 13, ci sono 12 personaggi che rappresentano praticamente cinque o sei compagnie multinazionali che controllano il mondo, che praticamente decidono cosa devono fare i politici, praticamente sono quelli che hanno comprato Trump o che Trump ha comprato, questo non lo sapremo mai! Fra queste persone ci sono i fondatori e i CEO di Google, Google Store, Meta, Musk… e poi a fianco c’è Trump.

Pd’A: Ascolta, Franko, quello che mi colpisce di questi personaggi e anche di alcune altre immagini sempre riferite a ritratti di persone, alcuni dei quali imbracciano dei mitra o delle armi che attualmente sono in mostra a Palazzo Lucarini a Trevi, è il sorriso feroce che hanno. Puoi parlarne?

Franko B: Quelli che imbracciano delle armi non sono uomini, per la maggior parte, ma sono bambini soldato. Sono immagini che vengono da tutto il mondo. Ad esempio, ce n’è uno che indossa una tuta: lui era un ragazzo soldato di 14 anni, volontario dell’ISIS, ai tempi dell’occupazione di una regione della Siria, se non sbaglio, Mosul o in Iraq, non ricordo con esattezza.

In questa immagine c’è una certa aggressività, anche in un’altra immagine dove si vede un altro bambino, quello che chiaramente sembra africano. Questa seconda immagine è una foto molto vecchia, avrà 20 anni se non di più. Il ragazzo ritratto all’epoca aveva 10-13 anni, poi è stato salvato da una ONG internazionale e penso che ora viva negli Stati Uniti. Non più tardi di 5 anni fa ha scritto un libro la cui copertina è proprio la foto da cui sono partito per fare il mio lavoro.

Parlando del sorriso, io non credo che loro vogliano mostrare la loro aggressività; secondo me mostrano la loro fragilità, la loro paura, la loro inadeguatezza. Ho raccolto molto materiale su questo argomento: i bambini soldato non sono solo un fenomeno recente e geograficamente riconducibile a una certa area del mondo. I bambini soldato sono esistiti anche in Europa sia nella prima che nella seconda guerra mondiale ed anche nelle guerre più vicine a noi nel tempo e nello spazio (ex Jugoslavia, Ucraina…). Su questo argomento c’è un film bellissimo del grande regista russo Andrei Tarkovskij, “L’infanzia di Ivan”: quando ho visto questo film, mi ha davvero rotto il cuore, così come un altro film “Europa” di Lars Von Trirer.

C’erano e ci sono tanti bambini soldati in tutti i conflitti che appartengono a differenti bande di combattenti. Nella maggior parte dei casi li rapiscono. Li rapiscono e li obbligano a fare i soldati, a volte uccidono la loro famiglia o li minacciano di farlo.

Ne ho incontrati alcuni. Circa 8 anni fa ho fatto un progetto su dei ragazzi/uomini che venivano dalla Nigeria; ne avevo incontrati due a Torino, li avevo intervistati. Mi dicevano che sono scappati dalla Nigeria, sono passati dal Sahara, poi in Libia. Questi ragazzi vivono un incubo, sono prede facili delle varie fazioni che vogliono conquistare il potere in questi paesi. Li rapiscono, li ricattano con metodi mafiosi e li obbligano a entrare nella loro banda ed è chiaro che gli avversari poi ti vogliono fare fuori. Questa dei bambini soldato è una cosa su cui lavoro da molto tempo, da quando ho cominciato a cucire. Lavoro molto sull’infanzia e anche sugli abusi di ogni genere: militari, di stato, di guerra, domestici, sessuali.

Pd’A: A proposito degli animali, mi viene in mente una cosa che ho visto anni fa in cui facevano vedere proprio un parallelo molto chiaro fra il sorriso, per esempio, e l’espressione di paura, che poi alla fine non è poi tanto diversa, nel senso che è sempre qualcosa che si manifesta, appunto, attraverso la bocca, la bocca aperta in un certo modo che mostra i denti. Quindi, sì, mi sembra che ci sia, appunto, una forma di analogia in questo. Ora, nelle immagini dell’Ultima Cena, di cui mi hai parlato prima, anche lì alcuni di questi personaggi sorridono, ma è un sorriso diverso, forse anche loro in qualche modo sono assolutamente inadeguati a quello che stanno facendo, chissà.

Franko B: Paura e stress non sono la stessa cosa. Quando il cane è stressato, la prima cosa che fa è tirar fuori la lingua. Le persone a volte pensano che il cane abbia sete, invece no, è una manifestazione dello stress. È un modo di esprimere lo stress; se la conosci, cerchi di fare qualcosa. Si manifesta specialmente quando agli animali non piace un altro animale o una persona e sono quindi in una situazione stressante. Lo facciamo anche noi: anche noi ci grattiamo la testa, mettiamo la mano davanti alla bocca, il naso, le orecchie, ci tocchiamo. Sono tutte cose che facciamo senza accorgercene, muoviamo le mani in una certa maniera, battiamo il piede su e giù… La paura è diversa, ha a che fare con sentirsi fuori dalla situazione, non si riesce a gestire in qualsiasi momento si verifichi.

Sì, sì, sono d’accordo con te. Certo che sono inadeguati e sono loschi, sono quelli che chiamiamo eminenze grigie. Gente che lavora dietro, sotto… Negli anni ’70 queste persone non le vedevi, ma c’erano gli Agnelli, per esempio, facevano le stesse cose, no? E non erano i soli.

Per questo lavoro basato sull’Ultima Cena ho scelto dei personaggi che hanno a che fare con il mondo dei media, dove non tutti vogliono essere riconosciuti, che se ci pensi bene è un tratto comune di tutte le varie eminenze grigie. Certo, poi ci sono personaggi che fanno parte di altri ambiti ma che potevano tranquillamente fare parte di questo cenacolo, come per esempio il CEO di BlackRock o altri…

E poi c’è secondo me un altro aspetto, che ritrovo specialmente nei ragazzi soldato: il mix fra adrenalina e terrore che leggi nelle loro facce è spesso legato alla situazione di conflitto in cui si trovano che può cambiare molto rapidamente. Io leggo la paura in questi sorrisi più che l’aggressività, gli occhi, gli occhi te lo dicono.

L’adrenalina si sente anche nei personaggi legati alla politica che spesso, secondo me, devono ricorrere a farmaci come anfetamine per poter essere dappertutto e sempre pronti a rispondere a tutte le domande… Si dice che Hitler era sempre sotto anfetamina e altre droghe; era il suo stesso medico a somministrargliele, queste sono cose provate.

Pd’A: Mi dicevi che il lavoro con i ricami l’hai cominciato diversi anni fa. Mi potresti un po’ raccontare come è venuto fuori e quando hai cominciato a fare questo tipo di lavori, come si sono evoluti nel tempo, come è cambiato, se è cambiato in qualche modo?

Franko B: Allora, io il ricamo lo chiamo cucito ed ho cominciato a farlo nel 2008. Io ero abbastanza famoso per le mie performance. Però ho sempre lavorato nel mio studio, facevo delle sculture o altri lavori che derivavano dalle mie performance, tipo tele; usavo il sangue e spesso il soggetto principale era il corpo.

Poi ai primi del 2008 mi contatta un certo Andrew Walker, uno studente che faceva un master al Royal College of Art nel dipartimento di Printing and Textile. Il Royal College of Art è una scuola molto importante che fa solo master e dottorati, in cui sono stato spesso invitato come visiting professor. E che cosa succede? Questo Andrew, con cui sono ancora amico, mi dice: “Io faccio tessitura, amo il tuo lavoro, ho visto che lavori con la tela e il tuo sangue, hai mai pensato di lavorare col cucito?”. Io ho detto: “No, non c’avevo mai pensato!”. Mi ricordo solo che da piccolo, quando ero in istituto alla Croce Rossa, un istituto per bambini che non andavano bene nella società o che erano abusati dai loro genitori in differenti maniere – fisica, sessuale, o che erano ritenuti ritardati – io cucivo le mie calze e le mie mutande; le dovevo cucire io quando si rompevano perché non avevo nessuno che me le ricomprava e le suore ogni tanto me le davano da cucire. Quella era la mia esperienza nel cucito, non ho mai pensato all’esperienza del cucire per creare. Grazie ad Andrew Walker, questo è successo.

Così ci incontriamo e lavoriamo per qualche mese. Ci troviamo due tre volte alla settimana, diventiamo amici e facciamo questo esercizio provando a combinare i nostri due lavori come in un botta e risposta in punta d’ago, lui da una parte io dall’altra, lui astratto io figurativo. Dove lui finisce io inizio e dove io finisco lui comincia.

Interessante, sì, ma dopo un po’, io dico: “Mi piace, ma dove andiamo con questo?”. Così io ho cominciato a pensare a costruire, a usare le mie immagini per fare un lavoro mio, no? Così io comincio nel 2008 a cucire le mie tele.

Nel 2010 faccio una mostra molto importante per me.dall titolo I STILL LOVE [ Che apparentemente delle eminenze grigie che non conoscevo prima hanno cercato di boicottare dietro le quinte senza riuscirci ] Durante il Giorno dell’Arte in Italia al PAC, Museo di Arte Contemporanea a Milano curata da Francesca Alfano Miglietti . Questa mostra è molto importante per me, ci sono un sacco di tele con questi soggetti personali, rappresentazione di me, rappresentazioni di fiori e i ragazzi, i bambini traumatizzati per la guerra e animali inbalzamati .

La mia pratica è sempre stata guidata dalle immagini. Immagini che vedo, che interpreto o che reimmagino nella mia testa, e sono proprio queste immagini che poi mi guidano e mi spingono a fare il lavoro. È così da più di 30 anni; anche le mie performance sono sempre state immagini, ricreare a me il teatro non mi interessa. Per me la performance è solo un mezzo, è il mezzo con cui io ho pensato che quell’immagine poteva vivere e poteva essere realizzata in modo democratico, democratico nel senso che non coinvolgo nessun altro, ma solo il mio corpo. Il mio corpo con cui assumo delle posizioni che possono mandare anche a farsi fottere ma con responsabilità: se uso la libertà che mi do, devo avere anche in mente anche il senso di responsabilità. Per tornare al cucito, il cucito è nato così, grazie a Walker.

Poi a un certo punto gliel’ho detto, lui c’era rimasto un po’ male: “Andrew, sì, è bello, grazie, ci siamo conosciuti, ti ringrazio per avermi fatto scoprire questo tipo di lavoro, ma io voglio usare questo tipo di lavoro per fare il mio”.

Un altro aspetto che mi attrae di questa pratica è che uomini che cucivano nella cultura artistica occidentale non ce n’erano. Questa tradizione esiste più in paesi come l’Iran, l’India, Pakistan per ragioni pratiche o per ragioni religiose. In India tutti i sarti sono uomini, se pensi che di solito i sarti, non quelli che riparano il vestito rotto or rammendano i calzini o la maglietta bucata, ma quelli che fanno i vestiti su misura che siano da uomo o da donna sono sempre uomini.

Poi non bisogna confondere l’arte con l’artigianato, cosa che a volte si fa quando si pensa agli stilisti famosi, ad esempio. Gli artisti si appropriano delle tecniche e le usano per fare il loro lavoro, usandole in modo personale e così le fanno diventare arte.

Pd’A: Senti Franco, vedo che usi sempre il filo rosso, il filo di lana per fare questi cuciti, perché?

Franko B: È vero, ma alla lana preferisco il cotone nella maggior parte dei casi. Lo preferisco perché il cotone è una pianta, la lana invece viene dagli animali; uso la lana solo se devo e cerco di usare lana non prodotta industrialmente perché trattano molto male gli animali, specialmente in Australia.

Ho scelto il rosso perché è come il sangue che esce dal corpo, come quando ci si taglia. Questa storia inizia quando io ero alla Croce Rossa per bambini ritardati. Ero ricoverato in questo istituto perché a 8 anni mi hanno diagnosticato la schizofrenia. A questo sono collegati traumi infantili e altre storie; ci sono profonde connessioni con la mia infanzia a cui la scelta del rosso è intimamente legata.

Ricordo che durante questo ricovero alla Croce Rossa in cui sono rimasto fra i 10 e i 14 anni, vedevo diversi medici psichiatri, psicologi, assistenti sociali… queste persone ti chiedevano cose come “Che cosa vuoi fare da grande?” o di disegnare, ad esempio. C’era una dottoressa che veniva, ti dava dei fogli e dei colori e ti diceva: “Disegna quello che vuoi”. Così ricordo che disegnavo alberi, un bambino che correva… Però io usavo solo la matita rossa. Lei poi mi chiede perché uso il rosso e io le ho detto: “Perché è il mio colore, il mio colore preferito”.

Dopo un anno o 6 mesi, adesso non mi ricordo, ho avuto un nuovo incontro con lei. Mi invita a colorare e a disegnare di nuovo, davanti a me ci sono i colori, ma questa volta manca il rosso, così io mi rifiuto di disegnare e le chiedo: “Ma dov’è il rosso?”. E lei mi risponde: “Ah, oggi non c’è” o qualcosa del genere. Non m’ha detto che l’aveva tolto, m’ha detto: “Ah, non c’è, usane un altro, ci sono tanti colori”. E io le ho risposto: “Non posso, non ce la faccio!”. Non so cosa è successo poi. Avrò avuto 11-12 anni. Però torniamo indietro.

Fino a 7 anni sono rimasto in un orfanotrofio. A 7 anni e qualcosa arriva una persona che dice di essere mia madre, ed era mia madre. Io non l’avevo mai vista, mai conosciuta, mi porta a casa. Mi mette in una scuola normale elementare. Per me è uno shock, un trauma. E dopo un mese o due che sono nella scuola di San Nazaro Sesia, provincia di Novara.

Arrivo in questa scuola, la maestra mi tiene vicino al suo tavolo, mi siedo; gli altri sono tutti di fronte alla cattedra mentre io sono a fianco. La maestra mi dice di disegnare. Io prendo la matita rossa e faccio il disegno di un bambino stick, tipo fiammifero, che fa la pipì. Lei si incazza con me, mi butta fuori dall’aula perché disegno questo stick con la faccetta molto primitivo, fatto di bastoncini con due gambette, due braccia e un piccolo cazzo che piscia, con i tratti della pipì, che poi in seguito anni dopo sono diventati i tratti del sangue che esce dalle mie vene.

Come ti ho detto, ero cresciuto in un orfanotrofio e probabilmente avrò visto tanti bambini fare la pipì. Ma la maestra vedendo il disegno si è incazzata, mi ha buttato fuori dalla classe, mi ha messo in un angolo con la testa contro l’angolo fino a quando non arriva mia madre a prendermi. Mia madre ovviamente si arrabbia con me, ma in tutto questo casino nessuno mi spiega il perché, nessuno mi spiega perché io non devo fare queste cose… anche qui ho usato il rosso, il rosso continua a tornare. Poi c’è il rosso della storia dell’arte: il rosso di Fontana, il rosso di Marc Rothko, il rosso di Francis Bacon… e di tanti quadri cattolici, specialmente.

Pd’A: Sì, beh, chiaramente c’è la questione anche del sacro in qualche modo; adesso, al di là del fatto che uno sia credente o no, però il sacro è comunque una cosa che ritorna e il rosso ha una sua centralità in questo…

Franko B: Adesso non so quanti anni hai tu, ma io sono cresciuto in Italia in istituzioni super cattoliche dagli 0 ai 7 anni e poi dai 10 ai 14 in strutture gestite da preti o suore. E poi ci sono le chiese, ci sono quelle immagini. Anch’io non sono credente, però mi ricordo quando ero alla Croce Rossa, forse avevo 12 – 13 anni, siamo andati a Marina di Massa in una delle loro colonie estive. E ricordo che ci avevano portato a Firenze una volta e ci avevano portato agli Uffizi. Questa è la prima volta che io ho visto l’arte e pur non capendo quello che avevo davanti mi era stato detto: “Questa è arte. Questi quadri, questa è la nostra cultura”. Ora, molte di queste immagini trattano temi religiosi ed hanno a che fare con la chiesa.

C’è un detto che usiamo a volte specialmente tra amici che sono nella scena come me, LGBTQ+: una volta cattolico, rimani sempre cattolico, anche se non pratichi la religione. Io infatti non dico neanche che sono ateo, io dico che sono un non credente. Io non credo. L’ateismo per me è un altro tipo di religione; invece io dico: “Il mio Dio non esiste, il tuo è morto”.

E poi chiaro, parliamo di sacro e religione, sono due cose differenti anche per me. L’arte sacra e l’arte religiosa si possono intrecciare, però non sempre. Io non vado in chiesa, mi sembra che abbia poco a che fare col sacro, ma è più un business. Ci sono tante religioni che non hanno nulla a che fare col sacro o con lo spirituale; anche lo spirituale è un’altra cosa.

Però è vero, essendo cresciuto romano cattolico, circondato da preti che mi chiedevano a 11-12 anni se mi toccavo, forse perché mi volevano toccare loro. Ora non mi ricordo se mi toccavano, però erano sempre abbastanza vicini quando ti parlavano e venivano in classe.

Ricordo un confronto con il prete del paese di Mergozzo, negli ultimi mesi che ero alla Croce Rossa. Questo monsignore veniva a dire la messa e a insegnarci religione. Un giorno gli dico: “Io non credevo in Dio”. Avevo 14 anni, è successo un casino, m’ha buttato fuori dalla classe, poi una suora mi ha chiamato dicendomi che se andava avanti così non avrei mai portato i pantaloni lunghi, cioè non sarei mai diventato un uomo o qualcosa del genere.

Tornando alla storia dell’arte, c’è ad esempio un quadro di Matthias Grünewald, pittore tedesco del 1500, un crocefisso pazzesco, marcio. Poi c’è ovviamente Francis Bacon.

Pd’A: Ascolta, l’idea del rosso poi porta con sé anche l’idea della fisicità, della corporalità e questo mi sembra un altro degli aspetti importanti del tuo lavoro.

Franko B: Certo, sai, io donavo sangue quando ero giovane e sono venuto in Inghilterra, non so come è successo, ma ho visto una pubblicità in cui dicevano che avevano bisogno di sangue, questo prima dello scandalo dell’HIV.

Io, essendo omosessuale dichiarato a 21 anni qui a Londra e vabbè, ho cominciato a donare sangue, poi nel 1983 è venuta fuori questa epidemia dell’HIV. Un giorno vado per donare il sangue, io donavo il sangue due volte all’anno, una volta ogni 6 mesi, e a metà dell’83 c’è un foglio nuovo in cui ti chiedono se fai sesso anale con uomini. E io ovviamente ho messo sì. Allora mi hanno detto: “Non puoi più donare il sangue”.

Ci sono rimasto male, allora ho pensato: “Va bene, se il mio sangue non lo volete lo uso”. Questo prima che io scoprissi di voler diventare un artista, prima che scoprissi che l’arte poteva salvare la mia vita. A questo proposito ci sono le scoperte fatte durante gli studi all’Università al Chelsea Art College, dove ho scoperto artisti come Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, Valie Export, gli Azionisti Viennesi. Fra gli Azionisti quello a cui mi sento più vicino era sicuramente Günter Brus per il suo senso etico.

In seguito sono diventato abbastanza amico di Hermann Nitsch, ma nonostante lui mi abbia invitato più volte a prendere parte alle sue azioni, io ho deciso di non partecipare per l’uso che faceva nelle sue cerimonie degli animali squarciati. Io devo lavorare col mio corpo e la maniera più democratica, più etica per me è quella di usare il mio sangue, neanche il corpo degli altri, a meno che non ci sia una collaborazione.

Il corpo è l’unica cosa mia che posso usare, ma il corpo io lo uso sempre, non solo nelle performance; la gente a volte mi dice: “Ah, ma tu sei l’artista che sanguinava, ah, non fai più le performance, sei l’artista che sanguina, hai smesso di sanguinare”. Io dico: “Ho smesso la strategia, ma parlo sempre del sangue, parlo sempre del corpo e non solo del mio. Ho sempre usato il mio corpo come tramite per parlare di cosa vuol dire essere qui, di cosa vuol dire essere vivi”. Questo è quello che cerco di fare. Se poi ci riesco questo non lo so, però io cerco di fare questo e poi c’è anche l’altra cosa che mi ricordo nei miei anni delle performance, alcune persone e alcuni giornalisti dicevano che io ero un mostro. “Guardate questo mostro!” dicevano… Io poi mi sono andato a guardare quale fosse l’etimologia della parola mostro, da dove viene fuori questa parola, ed ho scoperto che viene dal greco e significa uno che mostra, non uno che sciocca, uno che mostra. Il mostro non è un orrore, il mostro è uno che mostra.

Allora ho deciso di farla mia, ho preso questa posizione di essere un mostro; noi artisti dobbiamo essere mostri, dobbiamo mostrare. Poi esattamente col tempo e la conoscenza e incontrando artisti e filosofi sono cresciuto, le mie posizioni si sono fatte più chiare, tipo che l’artista ha il dovere e il diritto, il dovere di essere testimone. L’artista non è solo quello che dipinge, che fa scultura, ma il filosofo, il poeta, il musicista per me, lo scrittore e anche lo storico ha il dovere di testimoniare, di lasciare testimonianza.

Pd’A: Negli anni in cui facevi le performance, ma forse anche adesso, esiste un’idea di identificazione fra la tua opera e il tuo corpo? È una cosa che in qualche modo hai mai pensato?

Franko B: Sì, sono la stessa cosa, per me sono inseparabili. Il corpo per me è tutto. È la tela, il politico, il personale… a volte può essere anche poetico. Io spero, si tratta di una cosa importante che ha bellezza, che ha poesia, se no diventa è solo uno strumento di propaganda.

Pd’A: Tornando all’idea della fisicità, di cui abbiamo un po’ parlato prima, uno dei materiali che tu impieghi maggiormente è sicuramente quello della ceramica. Ecco, volevo sapere come sei entrato in contatto con questa materia e come la impieghi.

Franko B: È una storia che comincia dopo il 1983, penso che fosse settembre-ottobre ’83. All’epoca vivevo a Brixton e lavoravo nel turno del mattino come lavapiatti in un ristorante italiano a Londra. Finivo il lavoro intorno alle quattro del pomeriggio e passavo il tempo seduto a guardare la gente che passava per la strada del quartiere in cui vivevo. Un giorno una ragazza che avevo già notato nei giorni precedenti si ferma e inizia a parlare con me, si chiamava Sara, e mi chiede che cosa facevo nella vita visto che mi vedeva tutti i giorni. E io le rispondo in malo modo e poi le chiedo che cosa faceva lei: “Al mattino sono una assistente insegnante in una scuola elementare e al pomeriggio frequento dei corsi di ceramica nel quartiere, corsi finanziati dallo stato britannico”[ prima che una certa signora di nome Margareth Thatcher tagliasse i fondi per queste scuole serali per adulti ]. E mi invita a seguire con lei il corso di ceramica . Io non sono affatto convinto all’inizio ma poi decido di provare, così inizia la mia avventura nel mondo dell’arte. All’inizio facevo delle scatole con la ceramica, non ho mai fatto vasi o bicchieri, ma vere e proprie sculture che rappresentavano il mio stato d’animo, la mia solitudine, la mia infelicità, le mie paure, la mia rabbia…

Lì comincio a fare amicizia con uno dei miei docenti che si prendeva cura di me, credo il mercoledì e il martedì, si chiamava Keith , e mi dice: “Franko, perché non vai a scuola d’arte?”. E io gli dico: “Ah, non fa per me, non sono borghese, non… io no, non riesco a comunicare bene…”. Ma lui fa: “No, io sono sicuro che a te ti prendono”.

Così nell’85 faccio domanda alla Camberwell School of Art che aveva un corso di ceramica, però dovevo iniziare dai primi rudimenti. All’epoca pensavo che sarei andato avanti a fare ceramica. E invece, sono andato al colloquio, ho portato le mie ceramiche, i miei disegni – disegnavo anche il modello un amico e altre cose del genere per conto mio. In poche parole mi prendono. Faccio un anno lì, mentre sono lì a Camberwell a fare questo anno di preparazione in cui nei primi tre mesi puoi provare tutte le materie: due settimane di scultura, di pittura, di grafica, decorazione, si prova tutto anche il design e poi decidi per gennaio come indirizzare le tue scelte per il prossimo triennio.

Comunque, quando vado a Camberwell e comincio nel settembre dell’86 i corsi a livello base, faccio due settimane di tutto e decido di lasciare la ceramica per fare pittura, così faccio domanda a Chelsea School of Art per pittura e così faccio, mi prendono. Arrivo nell’87 a Chelsea a settembre, lì faccio ’87, ’88, ’89, ’90, giugno ’90, finisco.

Mentre sono a Chelsea faccio pittura il primo anno e mezzo, poi comincio a fare performance macchina da presa o fotografica. Il corso si chiamava così perché praticamente erano immagini che io creavo e che non riuscivo a dipingere o se le dipingevo erano considerate naïf. Ai miei docenti piacevano, pensavano che io avevo un futuro con questi lavori, ma io ho deciso di cambiare. A quei tempi mi piacevano molto Beuys, Paladino, Cucchi, Mark Rothko e David Smith, il grande scultore americano che lavorava con il metallo, poi a scuola d’arte ne conobbi molti altri

Ricordo anche la mia prima visita alla Tate Britain per la prima volta con una mia amica e lì c’era una stanza con i dipinti del artista americano Mark Rothko fu uno shock per me, è stato lì che ho capito che l’arte mi avrebbe salvato la vita, doveva salvarmi la vita, mi stava salvando la vita. In quel momento, per la prima volta nella mia vita, c’era qualcosa di fronte a me, una forma d’arte con cui mi potevo relazionare, in modo totale. Per me il linguaggio visivo non è solo quello che si vede – pittura, scultura, oggetti – ma parole, poesia, musica. La musica, specialmente la musica punk, mi ha ispirato molto, è stata quella a accendere la mia attenzione alla politica anarchica, agli animali…

Tornando alla ceramica. Dopo gli inizi che ti ho raccontato, vi ho rimesso mano nel 2017 quando ho deciso di aprire un mio studio di ceramica. La ceramica è importante soprattutto sul profilo biografico, è stata la chiave che mi ha aperto la porta dell’arte grazie a questa Sara che mi ha invitato ad andare con lei ai corsi serali a Brixton.

Adesso non sto facendo molto con la ceramica, ora sto cucendo e lavorando con cose che trovo o idee che mi arrivano, idee che hanno a che fare con la contemporaneità, con quello che succede nel mondo e come io lo vivo e di cui decido di essere testimone. Quello che voglio dire è che non ho un linguaggio che preferisco, non mi sento nello specifico uno scultore, un pittore, un ceramista o un performer: io sono Franko B.

Pd’A: Quando hai presentato la mostra a Trevi hai detto “Io sono un punk” e in qualche modo questo riassume un po’ tutto quello che hai detto poco fa, no? È un atteggiamento, quello del punk, che ancora oggi ha una sua verità da qualche parte?

Franko B : Il punk mi ha salvato la vita; mi ha portato a Londra. Il punk di cui parlo non è il punk rock dei Sex Pistols, una boy band creata ad hoc; loro sono diventati un simbolo, ma c’erano sicuramente cose migliori, gruppi come i Clash che erano molto più politici, più interessanti, secondo me, e poi soprattutto i gruppi punk anarchici, che erano pro-animali, anti-razzisti, anti-guerra… come i Crass, i Flux of Pink Indians Conflict, Penny Rimbaud e altri.

Il punk non è nato nel ’76. C’erano elementi punk molto prima, scrittori come quelli della Beat Generation, come Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Joanne Kyger, Patti Smith e, in termini di musica, molto prima di lei, gruppi musicali come i Velvet Underground erano punk per me. Punk nel loro comportamento, nella loro irriverenza verso l’industria, verso coloro che ti sfruttano e verso il mondo. E per me erano anche politicamente queer.

Il punk è stato molto importante per me all’inizio, è stato l’inizio della mia coscienza e letteralmente la mia educazione su ciò che stava accadendo nel mondo . Ancora oggi credo che questo elemento sia sempre presente come atteggiamento nel mondo dell’arte, ci sono esempi eccellenti come Duchamp o Manzoni, Cravan, John Latham, Lynda Benglis, l’artista che ha fatto la pubblicità su Art Forum, se non sbaglio, con il suo corpo nudo e indossando solo occhiali da sole e un pene di plastica piuttosto grande per dire che “Bisogna avere un cazzo per essere riconosciuti nel mondo dell’arte.” Per me oggi si potrebbe dire che ci sono artist come i fratelli Chapman , Sarah Lucas, Santiago Sera , Democracia e persino Cattelan che mostrano questa altitudine punk .

Pd’A: Sì, assolutamente, credo che sia un atteggiamento, un modo di essere che ancora oggi, al di là appunto delle cose più sbandierate, che poi a volte lasciano anche il tempo che trovano, come le creste, il modo di vestire o le spille da balia, il Punk in realtà sia qualcosa di profondamente autentico e che ancora oggi sia un modo di essere e di affrontare la vita assolutamente attuale, no?

Franko B: Sì, esatto, il Punk nel mio senso, nel senso di cui ne stiamo parlando, è un'attitudine tutti i giorni; è un rifiuto, è un istinto, una forma di dislessia, di autismo o di schizofrenia, se preferisci. Per quello che riguarda il look c’è un detto: “mai giudicare un libro dalla copertina”. Uno che lavora in banca con la cravatta e la camicia può essere più punk di me. Io trovo che negli ultimi 20 / 30 anni la gente più trasgressiva in tutte le possibile maniere che ho incontrato non lo mostrano nel modo di vestire o in come decorano il loro corpo ad esempio con tatuaggi e gioielli e lo stile dei loro cappelli . Questo per me è interessante e mi piace.

Pd’A: L’atteggiamento Punk ti interessa anche nel modo di costruire le immagini e nel modo in cui per esempio le parole si accostano alle immagini?

Franko B: Sì, quello che dici è vero, io penso che le immagini creino parole, e le parole creino immagini. Quando leggi una frase, una parola, ti viene in mente qualcosa, che spesso si traduce in un’immagine.

Ora le mie immagini sono chiaramente ispirate da quello che succede nel mondo. Il mio ruolo di artista è quello di in qualche maniera di dare testimonianza di quello che succede nel mondo. A volte queste immagini o parole vengono da me e a volte no, a volte le vedo su internet o sui giornali e mi spingono a fare qualcosa, a portarle su un altro piano.

Quella dell’artista è una logica predatoria: ci appropriamo di un linguaggio che c’è già e lo facciamo nostro per un secondo, ed è nostro fino al momento che non viene dato in pasto al pubblico. A quel punto l’immagine non appartiene più all’artista ma diventa patrimonio di chiunque la vede. Quello che voglio dire è che il linguaggio è un virus e mi piace questa cosa fluida. Secondo me è valida per ogni tipo di linguaggio o forma che ciò avvenga coscientemente o incoscientemente, è una cosa che ci tocca e entra dentro di noi. Per me l’idea di artista/genio non esiste, così come l’originalità; quello che facciamo è il frutto di quello che vedo, di quello che sento, di questa fluidità dei linguaggi. Noi ci appropriamo di un linguaggio e lo facciamo nostro per un momento. Ma dal momento che quello che fai passa dalla sfera privata a quella pubblica, non è più nostro, tocca qualcun altro e diventa qualcos’altro.

Pd’A: Un’ultima domanda, c’è qualcosa che ti fa paura?

Franko B: Siamo guidati nella nostra vita dalle nostre emozioni, dalle nostre necessità, dalle nostre esigenze, dalle nostre ossessioni e dalle nostre paure. L’unica cosa che realmente mi spaventa, che davvero mi fa paura, non è la morte fisica, ma è la mediocrità. Essere mediocre, per me è peggio. E infatti dico sempre ai miei studenti che preferisco aver a che fare con una persona che è difficile, problematica, come lo posso essere io ad esempio, che avere a che fare con una persona mediocre. Per me la mediocrità è uguale alla morte. Credo che sia meglio morire che essere mediocre. Questa è la mia posizione, una posizione sempre molto Punk, non credi?

Franko B (1960) è nato a Milano e si è trasferito a Londra nel 1979. La sua pratica artistica spazia dal disegno all’installazione, dalla performance alla scultura.

Pioniere della body art e artista performativo e attivista di spicco, Franko B utilizza il suo corpo come strumento per esplorare i temi del personale, del politico, del poetico, della resistenza, della sofferenza e del ricordo della nostra mortalità e vulnerabilità.

Franko B vive e lavora a Londra ed è professore di Scultura presso l’Accademia Albertina Di Belle Arti di Torino, Italia.

Ha presentato le sue opere a livello internazionale in numerosi contesti, tra cui: Tate Modern; ICA (Londra); South London Gallery; Arnolfini (Bristol); Palais des Beaux- Arts (Bruxelles); Beaconsfield Contemporary Art (Londra); Bluecoat Museum (Liverpool); Tate Liverpool; Ruarts Foundation (Mosca); PAC (Milano); Contemporary Art Centre (Copenaghen) e molti altri.

Le sue opere fanno parte delle collezioni della Tate, del Victoria and Albert Museum, della South London Gallery, della collezione permanente della città di Milano e di a/political Londra.

(English text)

Interview to Franko B

#paroladartista #artistinterview #intervistaartista #frankob

Pd’A: Hello Franko, who are these people?

Franko B: So, this series is based on the Last Supper, there are 13 in total. There are 12 characters who practically represent five or six multinational companies that control the world, and that decide what politicians should do. They are basically the ones who bought Trump or whom Trump bought, we’ll never know! Among these people are the founders and CEOs of Google, Google Store, Meta, Musk… and then next to them is Trump.

Pd’A: Listen, Franko, what strikes me about these characters and also some other images, always referring to portraits of people, some of whom are holding machine guns or weapons that are currently on display at Palazzo Lucarini in Trevi, is their fierce smile. Can you talk about that?

Franko B: Those holding weapons are not men, for the most part, but child soldiers. These are images that come from all over the world. For example, there’s one wearing a jumpsuit: he was a 14-year-old child soldier, an ISIS volunteer, at the time of the occupation of a region of Syria, if I’m not mistaken, Mosul or in Iraq, I don’t remember exactly.

In this image, there’s a certain aggressiveness, also in another image where you see another child, the one who clearly looks African. This second image is a very old photo, it must be 20 years old or more. The boy portrayed at the time was 10-13 years old, then he was saved by an international NGO and I think he now lives in the United States. No later than 5 years ago, he wrote a book whose cover is precisely the photo I started with for my work.

Speaking of the smile, I don’t believe they want to show their aggressiveness; in my opinion, they show their fragility, their fear, their inadequacy. I have collected a lot of material on this subject: child soldiers are not only a recent phenomenon and geographically confined to a certain area of the world. Child soldiers also existed in Europe in both the First and Second World Wars and also in the wars closer to us in time and space (former Yugoslavia, Ukraine…). There’s a beautiful film on this topic by the great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, “Ivan’s Childhood”: when I saw this film, it really broke my heart, as did another film “Europa” by Lars Von Trier.

There were and are many child soldiers in all conflicts who belong to different fighting groups. In most cases, they are kidnapped. They are kidnapped and forced to be soldiers; sometimes their family is killed or threatened with it.

I have met some of them. About 8 years ago, I did a project on boys/men who came from Nigeria; I met two in Turin, I interviewed them. They told me that they fled Nigeria, passed through the Sahara, then Libya. These boys live a nightmare, they are easy prey for the various factions that want to conquer power in these countries. They kidnap them, blackmail them with mafia methods, and force them to join their gang, and it’s clear that the opponents then want to get rid of you. Child soldiers are something I’ve been working on for a long time, ever since I started sewing. I work a lot on childhood and also on abuses of all kinds: military, state, war, domestic, sexual.

Pd’A: Speaking of animals, something comes to mind that I saw years ago, which showed a very clear parallel between a smile, for example, and an expression of fear, which ultimately isn’t that different, in the sense that it’s always something that manifests itself, precisely, through the mouth, the mouth open in a certain way that shows the teeth. So, yes, it seems to me that there is, indeed, a form of analogy in this. Now, in the images of the Last Supper, which you told me about earlier, some of these characters also smile, but it’s a different smile, perhaps they too are somehow completely inadequate for what they are doing, who knows.

Franko B: Fear and stress are not the same thing. When a dog is stressed, the first thing it does is stick its tongue out. People sometimes think the dog is thirsty, but no, it’s a manifestation of stress. It’s a way of expressing stress; if you know it, you try to do something. It manifests especially when animals don’t like another animal or person and are therefore in a stressful situation. We do it too: we also scratch our heads, put our hand in front of our mouth, nose, ears, we touch ourselves. These are all things we do without realizing it, we move our hands in a certain way, we tap our foot up and down… Fear is different, it has to do with feeling out of a situation, you can’t manage it whenever it occurs.

Yes, yes, I agree with you. Of course, they are inadequate and they are shady, they are what we call gray eminences. People who work behind the scenes, underneath… In the 70s you didn’t see these people, but there were the Agnelli’s, for example, doing the same things, right? And they weren’t the only ones.

For this work based on the Last Supper, I chose characters who have to do with the world of media, where not everyone wants to be recognized, which, if you think about it, is a common trait of all the various gray eminences. Of course, then there are characters who are part of other fields but who could easily have been part of this cenacle, such as the CEO of BlackRock or others…

And then, in my opinion, there’s another aspect, which I find especially in child soldiers: the mix of adrenaline and terror you read on their faces is often linked to the conflict situation they are in, which can change very rapidly. I read fear in these smiles more than aggression, their eyes, their eyes tell you.

Adrenaline is also felt in characters linked to politics who often, in my opinion, have to resort to drugs like amphetamines to be everywhere and always ready to answer all questions… It is said that Hitler was always on amphetamines and other drugs; his own doctor administered them to him, these are proven facts.

Pd’A: You told me that you started working with embroidery several years ago. Could you tell me a bit about how it came about and when you started doing this type of work, how it evolved over time, how it changed, if it changed in any way?

Franko B: So, I call embroidery “sewing” and I started doing it in 2008. I was quite famous for my performances. But I always worked in my studio, I made sculptures or other works that derived from my performances, like canvases; I used blood and often the main subject was the body.

Then in early 2008, a certain Andrew Walker, a student doing a master’s at the Royal College of Art in the Printing and Textile department, contacted me. The Royal College of Art is a very important school that only offers master’s and doctorates, where I was often invited as a visiting professor. And what happens? This Andrew, with whom I am still friends, tells me: “I do weaving, I love your work, I’ve seen that you work with canvas and your blood, have you ever thought of working with sewing?” I said: “No, I had never thought of it!” I only remember that as a child, when I was in the Red Cross institute, an institute for children who didn’t fit into society or who were abused by their parents in different ways – physical, sexual, or who were considered retarded – I sewed my socks and my underwear; I had to sew them myself when they broke because I had no one to buy me new ones and the nuns sometimes gave them to me to sew. That was my experience with sewing, I never thought about the experience of sewing to create. Thanks to Andrew Walker, this happened.

So we met and worked for a few months. We met two or three times a week, became friends and did this exercise trying to combine our two works like a back and forth with a needle, him on one side, me on the other, him abstract, me figurative. Where he ends, I begin, and where I end, he begins.

Interesting, yes, but after a while, I said: “I like it, but where are we going with this?” So I started thinking about building, about using my images to do my own work, right? So in 2008, I started sewing my canvases.

In 2010, I had a very important exhibition for me. Called I STILL LOVE [ Which apparently some grey eminences I didn’t know before tried to boycott it behind the scenes without success] During Art Day in Italy at PAC, Museum of Contemporary Art in Milan curated by Francesca Alfano Miglietti. This exhibition is very important to me, there are a lot of canvases with these personal subjects, representations of me, representations of flowers and boys, children traumatized by war and stuffed animals.

My practice has always been guided by images. Images that I see, that I interpret or that I re-imagine in my head, and it is precisely these images that then guide me and push me to do the work. It has been like this for more than 30 years; even my performances have always been images, recreated by me, theater doesn’t interest me. For me, performance is just a medium, it is the medium with which I thought that image could live and could be realized in a democratic way, democratic in the sense that I don’t involve anyone else, but only my body. My body with which I take positions that can even go to hell but with responsibility: if I use the freedom I give myself, I must also keep in mind the sense of responsibility. To go back to sewing, sewing was born like this, thanks to Walker.

Then at a certain point I told him, he was a bit upset: “Andrew, yes, it’s nice, thank you, we met, thank you for making me discover this type of work, but I want to use this type of work to do my own.”

Another aspect that attracts me to this practice is that there were no men who sewed in Western artistic culture. This tradition exists more in countries like Iran, India, Pakistan for practical or religious reasons. In India, all tailors are men, if you think that usually tailors, not those who repair broken clothes or mend socks or torn shirts, those who make custom-made clothes, whether for men or women, are always men.

Then one must not confuse art with craftsmanship, which sometimes happens when thinking of famous designers, for example. Artists appropriate techniques and use them to do their work, using them in a personal way and thus making them art.

Pd’A: Listen, Franko, I see you always use red thread, wool thread, for these embroideries. Why?

Franko B: That’s true, but I prefer cotton to wool in most cases. I prefer it because cotton is a plant, whereas wool comes from animals; I only use wool if I have to and I try to use non-industrially produced wool because they treat animals very badly, especially in Australia.

I chose red because it’s like blood coming out of the body, like when you cut yourself. This story began when I was at the Red Cross for retarded children. I was hospitalized in this institution because at the age of 8 I was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Childhood traumas and other stories are connected to this; there are deep connections with my childhood to which the choice of red is intimately linked.

I remember that during this stay at the Red Cross, where I remained between the ages of 10 and 14, I saw various psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers… these people would ask you things like “What do you want to be when you grow up?” or to draw, for example. There was a doctor who would come, give you sheets of paper and colors and say: “Draw whatever you want.” So I remember drawing trees, a child running… But I only used the red pencil. She then asked me why I used red and I told her: “Because it’s my color, my favorite color.”

After a year or 6 months, I don’t remember now, I had another meeting with her. She invited me to color and draw again, there were colors in front of me, but this time red was missing, so I refused to draw and asked her: “But where is the red?” And she replied: “Oh, it’s not here today” or something like that. She didn’t tell me she had removed it, she said: “Oh, it’s not here, use another one, there are many colors.” And I replied: “I can’t, I just can’t!” I don’t know what happened then. I must have been 11-12 years old. But let’s go back.

Until I was 7, I stayed in an orphanage. At just over 7, someone arrived claiming to be my mother, and it was my mother. I had never seen her, never known her, she took me home. She put me in a normal elementary school. For me, it was a shock, a trauma. I arrived at this school in San Nazaro Sesia, in the province of Novara. The teacher kept me close to her table, I sat down; the others were all in front of the desk while I was next to it. The teacher told me to draw. I took the red pencil and drew a stick figure child, like a matchstick, peeing. She got angry with me, threw me out of the classroom because I drew this very primitive stick figure, made of sticks with two little legs, two arms and a small dick peeing, with the lines of pee, which many years later became the lines of blood coming out of my veins.

As I told you, I had grown up in an orphanage and I had probably seen many children pee. But the teacher, seeing the drawing, got angry, threw me out of the class, put me in a corner with my head against the corner until my mother came to pick me up. My mother, of course, got angry with me, but in all this mess, no one explained why, no one explained why I shouldn’t do these things… here too I used red, red keeps coming back. Then there’s the red in art history: the red of Fontana, the red of Mark Rothko, the red of Francis Bacon… and many Catholic paintings, especially.

Pd’A: Yes, well, clearly there’s also the question of the sacred in some way; now, regardless of whether one is a believer or not, the sacred is still something that returns and red has a central role in this…

Franko B: Now I don’t know how old you are, but I grew up in Italy in super Catholic institutions from 0 to 7 years old and then from 10 to 14 in facilities run by priests or nuns. And then there are the churches, there are those images. I am also not a believer, but I remember when I was at the Red Cross, maybe I was 12-13 years old, we went to Marina di Massa to one of their summer camps. And I remember they took us to Florence once and took us to the Uffizi. This was the first time I saw art and even though I didn’t understand what was in front of me, I was told: “This is art. These paintings, this is our culture.” Now, many of these images deal with religious themes and have to do with the church.

There’s a saying we sometimes use, especially among friends who are in the scene like me, LGBTQ+: once a Catholic, always a Catholic, even if you don’t practice the religion. In fact, I don’t even say I’m an atheist, I say I’m a non-believer. I don’t believe. Atheism, for me, is another type of religion; instead, I say: “My God doesn’t exist, yours is dead.”

And then, of course, we talk about sacred and religion, they are two different things even for me. Sacred art and religious art can intertwine, but not always. I don’t go to church, it seems to have little to do with the sacred, but it’s more of a business. There are many religions that have nothing to do with the sacred or with the spiritual; even the spiritual is another thing.

But it’s true, having grown up Roman Catholic, surrounded by priests who would ask me at 11-12 years old if I was touching myself, perhaps because they wanted to touch me. Now I don’t remember if they touched me, but they were always quite close when they talked to you and came to class.

I remember a confrontation with the village priest of Mergozzo, in the last months I was at the Red Cross. This Monsignor would come to say mass and teach us religion. One day I told him: “I didn’t believe in God.” I was 14, a mess happened, he threw me out of the class, then a nun called me saying that if I kept going like this I would never wear long pants, meaning I would never become a man or something like that.

Returning to art history, there is, for example, a painting by Matthias Grünewald, a German painter from the 1500s, a crazy, rotten crucifix. Then there is obviously Francis Bacon.

Pd’A: Listen, the idea of red also carries with it the idea of physicality, of corporality, and this seems to me to be another important aspect of your work.

Franko B: Of course, you know, I used to donate blood when I was young and I came to England, I don’t know how it happened, but I saw an advertisement saying they needed blood, this was before the HIV scandal.

Being an openly homosexual man at 21 here in London, I started donating blood. Then, in 1983, the HIV epidemic emerged. One day I went to donate blood, I used to donate twice a year, once every 6 months, and in mid-1983 there was a new form asking if you had anal sex with men. And I, of course, answered yes. So they told me: “You can no longer donate blood.”

I was upset, so I thought: “Okay, if you don’t want my blood, I’ll use it myself.” This was before I discovered I wanted to become an artist, before I discovered that art could save my life. In this regard, there are the discoveries I made during my studies at Chelsea Art College, where I discovered artists like Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, the Viennese Actionists. Among the Actionists, the one I feel closest to was certainly Günter Brus for his ethical sense.

Later, I became quite good friends with Hermann Nitsch, but even though he invited me several times to take part in his actions, I decided not to participate because of his use of torn-apart animals in his ceremonies. I have to work with my body, and the most democratic, most ethical way for me is to use my blood, not even other people’s bodies, unless there’s a collaboration.

The body is the only thing of mine that I can use, but I always use my body, not only in performances; people sometimes tell me: “Oh, but you’re the artist who bled, oh, you don’t do performances anymore, you’re the artist who bleeds, you’ve stopped bleeding.” I say: “I’ve stopped the strategy, but I always talk about blood, I always talk about the body and not just mine. I’ve always used my body as a medium to talk about what it means to be here, what it means to be alive.” That’s what I try to do. Whether I succeed, I don’t know, but I try to do this, and then there’s also the other thing I remember from my performance years, some people and some journalists used to say that I was a monster. “Look at this monster!” they would say… I then went to look at the etymology of the word “monster,” where this word comes from, and I discovered that it comes from Greek and means “one who shows,” not “one who shocks,” “one who shows.” A monster is not a horror, a monster is one who shows.

So I decided to make it my own, I took this position of being a monster; we artists must be monsters, we must show. Then, with time and knowledge and meeting artists and philosophers, I grew, my positions became clearer, like that the artist has the duty and the right, the duty to be a witness. The artist is not just someone who paints, who sculpts, but the philosopher, the poet, the musician for me, the writer, and also the historian has the duty to witness, to leave testimony.

Pd’A: In the years you were doing performances, but perhaps even now, is there an idea of identification between your work and your body? Is that something you’ve ever thought about in some way?

Franko B: Yes, they are the same thing, for me they are inseparable. The body for me is everything. It’s the canvas, the political, the personal… sometimes it can also be poetic. I hope, it’s about something important that has beauty, that has poetry, otherwise it just becomes a propaganda tool.

Pd’A: Going back to the idea of physicality, which we talked about a bit earlier, one of the materials you use most is certainly ceramics. So, I wanted to know how you came into contact with this material and how you use it.

Franko B: It’s a story that begins after 1983, I think it was September-October ’83. At the time I was living in Brixton and working the morning shift as a dishwasher in an Italian restaurant in London. I finished work around four in the afternoon and spent my time sitting and watching people pass by on the street in the neighborhood where I lived. One day a girl I had already noticed in previous days stopped and started talking to me, her name was Sara, and she asked me what I did for a living since she saw me every day. And I answered her rudely and then asked her what she did: “In the morning I’m a teaching assistant at an elementary school and in the afternoon I attend ceramic classes in the neighborhood, classes funded by the British state” [before a certain lady named Margaret Thatcher cut funding for these adult evening schools]. And she invited me to join her ceramic class. I wasn’t at all convinced at first but then I decided to try, and so my adventure in the world of art began. At first I made boxes with ceramics, I never made vases or cups, but real sculptures that represented my state of mind, my loneliness, my unhappiness, my fears, my anger…

There I started making friends with one of my teachers who took care of me, I think on Wednesdays and Tuesdays, his name was Keith, and he told me: “Franko, why don’t you go to art school?” And I told him: “Oh, it’s not for me, I’m not bourgeois, I… I can’t communicate well….” But he said: “No, I’m sure they’ll take you.”

So in ’85 I applied to Camberwell School of Art which had a ceramics course, but I had to start from the basic rudiments. At the time I thought I would continue to do ceramics. Instead, I went to the interview, I brought my ceramics, my drawings – I also drew a friend’s model and other things like that on my own. In short, they took me. I spent a year there, while I was at Camberwell doing this preparatory year where in the first three months you can try all subjects: two weeks of sculpture, painting, graphics, decoration, you try everything including design and then you decide by January how to direct your choices for the next three years.

Anyway, when I went to Camberwell and started the basic courses in September ’86, I did two weeks of everything and decided to leave ceramics to do painting, so I applied to Chelsea School of Art for painting and so I did, they took me. I arrived at Chelsea in ’87 in September, I was there ’87, ’88, ’89, ’90, June ’90, I finished.

While at Chelsea, I did painting for the first year and a half, then I started doing performance for camera and photographic works . The course was called Alternative Learning Media in the fine art contest . what i did there practically were images that I was creating that I couldn’t paint or if I painted them they were considered naive. My painting teachers liked them, they thought I had a future with these works, but I decided to change. At that time I was aware and really liked artist like Beuys, Paladino, Cucchi, Mark Rothko and David Smith, the great American sculptor who worked with metal, then at art school I met many others. But one that really open my eyes and inspired my worksin the last 2 years at Chelsea was Robert Marpplethorpe for me he was one of the first queer and punk artist and then the artist’s Valie Export , Gunter Brus and Gina Pane

Crucially well before I also remember my first visit to Tate Britain around 1984 for the first time with a friend of mine and there was a room with paintings by the American artist Mark Rothko, it was a shock for me, it was there that I understood that art would save my life, it had to save my life, it was saving my life. At that moment, for the first time in my life, there was something in front of me, an art form that I could relate to, in a total way. For me, visual language is not just what you see – painting, sculpture, objects – but words, poetry, music. Music, especially punk music, inspired me a lot, it was what ignited my attention to anarchic politics, to animals… but also classical music.

Returning to ceramics. After the beginnings I told you about, I took it up again in 2017 when I decided to open my equped own ceramic studio. Ceramics are important especially from a biographical profile, it was the key that opened the door to art for me thanks to this Sara who invited me to go with her to evening classes in Brixton.

Now I’m not doing much with ceramics, now I’m sewing and working with things I find or ideas that come to me, ideas that have to do with contemporaneity, with what is happening in the world and how I experience it and of which I decide to be a witness. What I mean is that I don’t have a preferred language, I don’t specifically feel like a sculptor, a painter, a ceramist or a performer: I am Franko B.

Pd’A: When you presented the exhibition in Trevi, you said, “I am a punk,” and in some way, this summarizes everything you just said, doesn’t it? Is that attitude, the punk attitude, still relevant somewhere today?

Franko B: Punk saved my life; it drew me to London. The punk I’m talking about isn’t the punk rock of the Sex Pistols, to me a manufactured boy band; they became a symbol, but there were definitely better things, groups like The Clash who were much more political, more interesting, in my opinion, and then especially the anarchist Punk groups,that where pro-animal, anti-racism, anti-war…like Crass , flux of pink indians Conflict , Penny Rimbaud and more .

Punk didn’t start in ’76. There were punk elements much earlier, writers like those of the Beat Generation, like Jack Kerouac,William Burroughs ,Allen Ginsberg, Joanne Kyger , Patti Smith and in terms of music long before Patti Smith , musical groups like the Velvet Underground, and the New York band Television to citcing some , were punk to me. Punk in their behavior, in their irreverence towards the industry, towards those who exploit you and the world. and also to me they where politically Queer .

Punk was very important to me in the beginning it was the beginning of my concience and literally my education ofwhat was happening in the world . Even today, I believe this element is always present as an attitude in the art world, there are excellent examples like Duchamp or Manzoni, Cravan, John Latham, Lynda Benglis, the artist who did the advertisement in Art Forum, if I’m not mistaken, with her naked body and wearing only sunglasses and a rather large plastic dick to say “you have to have a dick to be recognized in the art world.” Today one could say that the Chapman brothers , Sarah Lucas , Santiago Sera , Democracia and even Cattelan have punks attitudine .

Pd’A: Yes, absolutely, I believe it’s an attitude, a way of being that even today, beyond the more flaunted things, which sometimes don’t last, like mohawks, the way of dressing, or safety pins, Punk is actually something deeply authentic and even today it’s an absolutely current way of being and facing life, isn’t it?

Franko B: Yes, exactly, Punk in my sense, in the sense we are talking about, is an everyday attitude; it’s a refusal, it’s an instinct, a form of dyslexia, autism, or schizophrenia, if you prefer. As for the look, there’s a saying: “never judge a book by its cover.” Someone who works in a bank with a tie and a shirt can be more punk than me. I find that in the last 20 /30 years, the most transgressive people I encoutered don’t show it in their way of how they dress or theirs body’s decorations or color hair . most times people that looks “normal” are more is interesting to me and I like it.this is why i alway say never judge a book by its cover

Pd’A: Are you also interested in the Punk attitude in the way you construct images and, for example, the way words are combined with images?

Franko B: Yes, what you say is true, I think images create words, and words create images. When you read a phrase, a word, something comes to mind, which often translates into an image.

Now my images are clearly inspired by what is happening in the world. My role as an artist is to somehow bear witness to what is happening in the world. Sometimes these images or words come from me and sometimes not, sometimes I see them on the internet or in newspapers and they push me to do something, to take them to another level.

The artist’s is like a a predatory: we appropriate a language that already exists and make it our own for a second, and it’s ours until it’s given to the public domain . At that point, the image no longer belongs to the artist but becomes the heritage of anyone who sees it. What I mean is that language is a virus and I like this fluid thing. In my opinion, it applies to every type of language or form, whether it happens consciously or unconsciously, it’s something that affects us and enters us. For me, the idea of artist/genius does not exist, just like originality; what I do is the result of what I see, what I feel, of this fluidity of languages. We appropriate a language and make it our own for a moment. But from the moment what you do passes from the private to the public sphere, it is no longer ours, it touches someone else and becomes something else.

Pd’A: One last question, is there anything that scares you?

Franko B: We are guided in our lives by our emotions, our needs, our demands, our obsessions, and our fears. The only thing that truly frightens me, that really scares me, is not physical death, but mediocrity. Being mediocre, for me, is worse. And in fact, I always tell my students that I prefer to deal with a person who is difficult, problematic, as I can be, for example, than to deal with a mediocre person. For me, mediocrity is equal to death. I believe it’s better to die than to be mediocre. This is my position, a very Punk position, don’t you think?

Franko B (1960) was born in Milan and CV moved to London in 1979. His practice

spans drawing, installation, performance and

sculpture.

A pioneer of body art and a leading performance artist and activist, Franko

B uses his body as a tool to explore the themes of the personal, political, poetic, resistance, suffering and the reminder of our own mortality and vulnerability.

Franko B lives and works in London and is a professor of Sculpture at L’Accademia Albertina Di Belle Arti di Torino, Italy.

He has presented work internationally at: Tate Modern; ICA (London); South London Gallery; Arnolfini (Bristol); Palais des Beaux- Arts (Brussels); Beaconsfield Contemporary Art (London); Bluecoat Museum (Liverpool); Tate Liverpool; Ruarts Foundation (Moscow); PAC (Milian); Contemporary Art Centre (Copenhagen) and many more.

His works are in the collections of the Tate, Victoria and Albert Museum, South London Gallery, the permanent collection of the city of Milan and a/political, London.

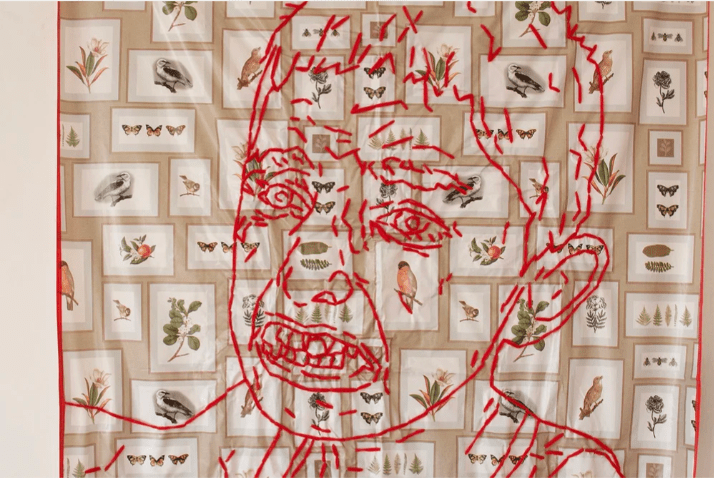

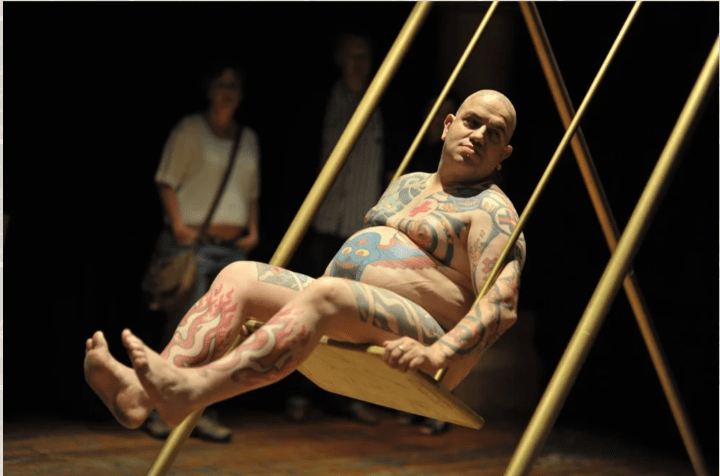

“I apologize”

Veduta parziale della mostra e dettagli

PH Gabriele Provenzano

Palazzo Luccarini , Museo di arte contemporanea , Trevi (PG)

“I apologize”

Veduta parziale della mostra e dettagli

PH Gabriele Provenzano

Palazzo Luccarini , Museo di arte contemporanea , Trevi (PG)

“I apologize”

The Last Supper (Jesus and the 12 Billionaires):

45x61cm Lana su tela di lino (2025)

PH Gabriele Provenzano

Palazzo Luccarini , Museo di arte contemporanea , Trevi (PG)

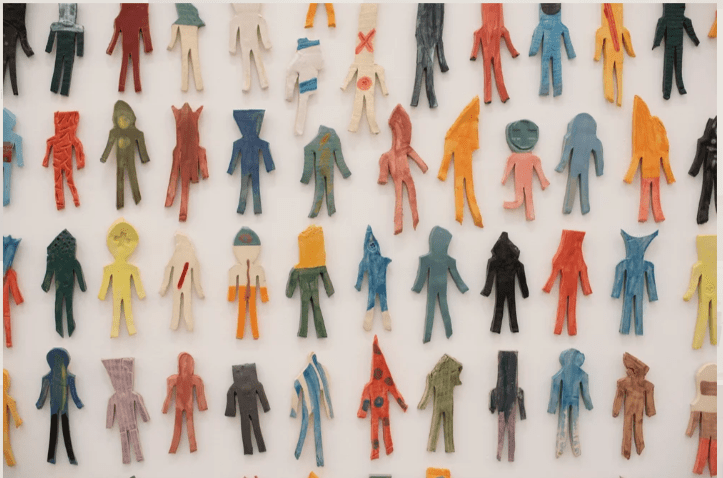

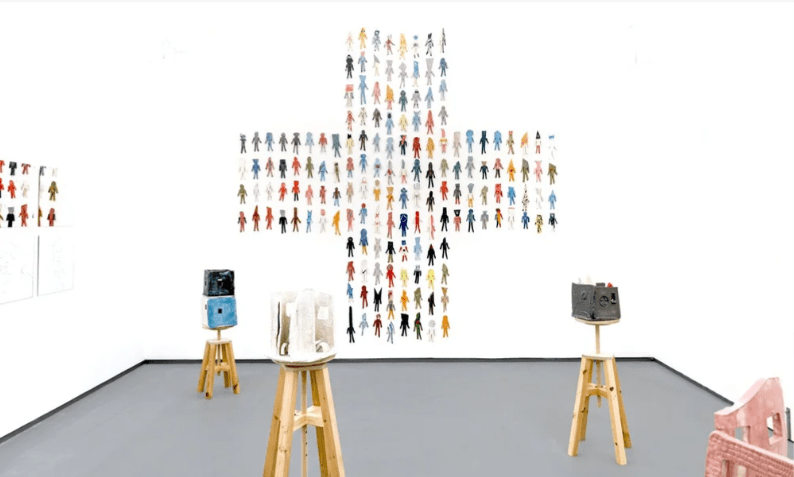

“Unloved“

exhibition at Rua Red, Dublin

PH Thomas Qualmann

“Unloved“

exhibition at Rua Red, Dublin

PH Thomas Qualmann

“I’m Thinking of You“

performance by Franko B with music composed and performed by Helen Ottaway 2009/2022

“Broken“

installazione composta di frammenti di ceramiche rotte

(2019)

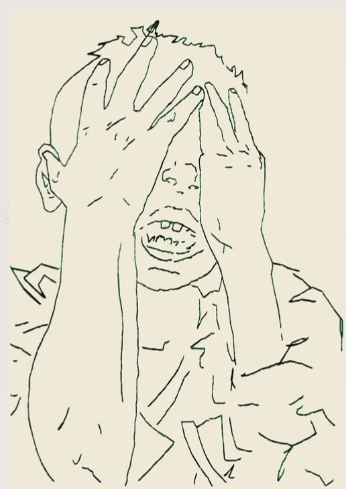

Disegno

“I Miss You“

performance

(1999-2005)