(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #cristianocarotti #intervistaartista #artistinterview

Pd’A: Ciao Cristiano, che importanza ha l’idea di sacro nel tuo lavoro?

C.C.: Il sacro è oggetto centrale della mia ricerca.

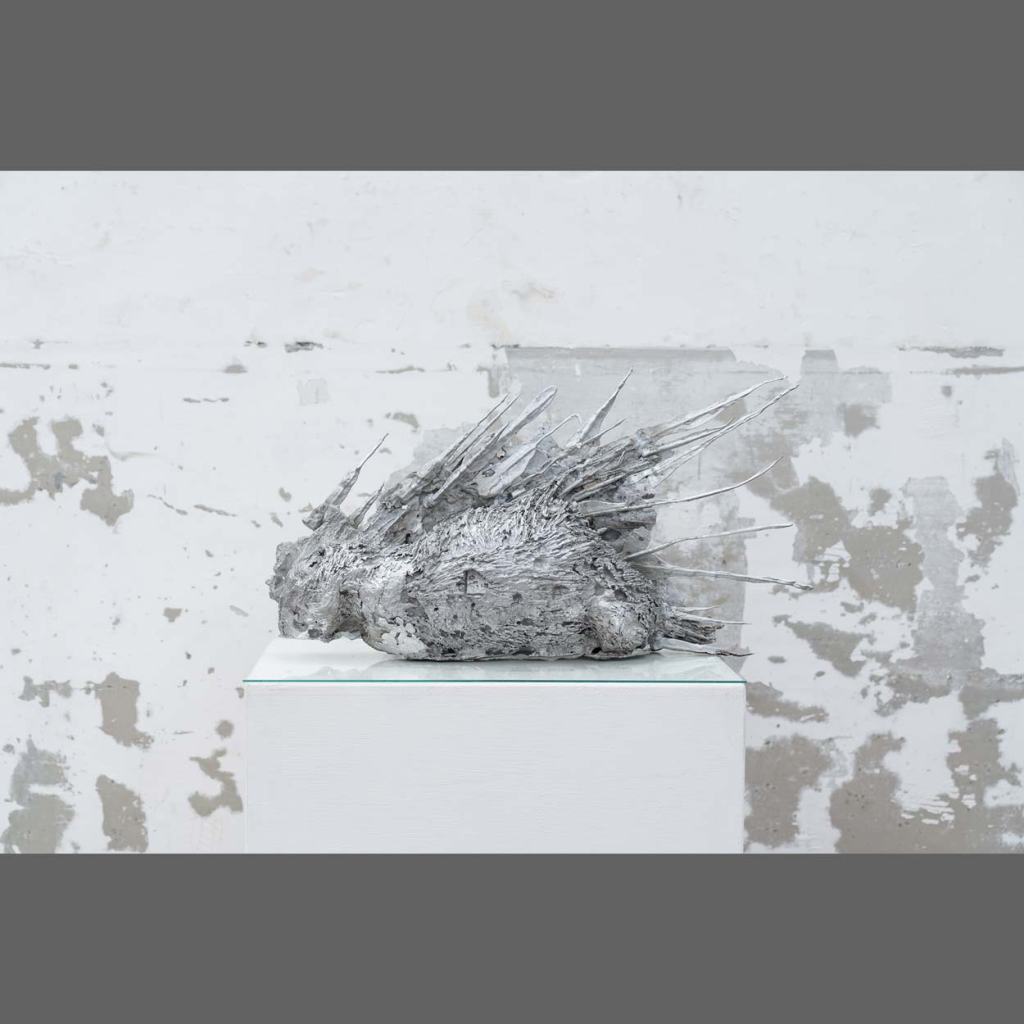

Definirei tutto il mio lavoro un costante tentativo gotico di slancio verso il sacro. La scultura è alchimia e magia. Durante la pratica, più o meno consapevolmente, senza volerlo ci si trova a compiere rituali, per cui la tensione verso il sacro diviene condizione e stato necessario. Nel realizzare le fusioni in alluminio da calchi di animali ritrovati investiti in strada ad esempio, mi sono trovato a mettere in scena un rito ben preciso.

Dapprima il calco in cemento, poi il fuoco e la benzina per pulirlo e disinfettarlo, ottenendo infine una sorta di maschera mortuaria fusa in alluminio.

“L’alchimia” come scrive Eugène Canseliet, nella prefazione a “Il mistero delle Cattedrali” di Fulcanelli, “ non è altro che il risveglio della vita segretamente assopita sotto il pesante involucro dell’essere e la grezza scorza delle cose, derivanti da un certo stato d’animo molto prossimo alla grazia reale ed efficace. Sui due piani universali, dove siedono insieme la materia e lo spirito, il processo è assoluto e consiste in una permanente purificazione fino alla purificazione più completa. A questo scopo niente è più utile, per quel che riguarda il modo d’operare, dell’apoftegma antico e così preciso nella sua imperativa concisione: Salve et coagula; dissolvi e coagula” . La tecnica semplice e lineare, esige sincerità, decisione e pazienza, ed ha bisogno d’immaginazione, ahimè!” Volontà ed immaginazione sono le componenti fondamentali per compiere la magia secondo Paracelso, per questa ragione credo che ogni opera d’arte sia un atto magico, e quindi sacro.

Come i costruttori di cattedrali, e come indica Fulcanelli stesso, mi piace fondare il lavoro scultoreo sul materiale di risulta, la scoria del mondo, la cosiddetta pietra d’angolo , che sia esso la carcassa di un animale trovato per strada, i resti di un’autovettura, del cemento o le componenti di una vecchia carpenteria.E’ la scoria ad essere destinata a divenire Oro alchemico.

Pd’A: E’ sempre stato questo il centro dei tuoi interessi? Nel tempo come si è evoluto il tuo lavoro?

C.C.: L’iconografia sacra mi ha sempre affascinato. All’inizio del mio percorso la reinterpretazione di certe immagini bibliche e cristologiche mi interessava molto.Nel 2013 ad esempio, una delle mie prime installazioni, dal titolo Goliat, per la mostra +50 a Spoleto Festival , era una sorta di altare gotico in cui la testa del gigante era ricavata dalla cabina di un TIR, con tanto di luci e bassorilievi sulla carrozzeria. Sempre di quegli anni è una serie di lavori scultorei che vedevano come soggetti dei “black block” o comunque dei manifestanti in felpa nera e cappuccio, messi in relazione all’iconografia cristiana dei santi. “Tredici” era il titolo di una istallazione al MLAC di Roma nel 2014, con tredici estintori bianchi in gesso, in riferimento a Cristo e agli apostoli, ed all’estintore di cui era “armato” Carlo Giuliani. Poi c’è stato un cambiamento nella mia ricerca, che coincide con l’incontro con il pensiero di Carl Gustav Jung e con la mostra “Dove Sono gli Ultras” del 2016 alla White Noise di Roma. Sulle bandiere realizzate per quel progetto, in un ibrido tra scultura e pittura, hanno iniziato a comparire diverse figure animali, in relazione agli archetipi ed ai simboli che essi incarnano nella cultura ultras ed in generale, nel nostro inconscio.

Un punto di svolta fondamentale è stato l’incontro con la ceramica, che ha coinciso con il periodo del covid e con il recupero, per me, di un contatto perduto con la natura e con la mia terra, l’Umbria. La ceramica è una pratica ancestrale ed attraverso lo studio di questo medium, il focus si è spostato in modo deciso sulla natura, grazie anche all’incontro con l’artista, ceramista e designer Christopher Domiziani. Con Christopher e con la sua azienda, la Domiziani di Torgiano, ho avuto la fortuna di sviluppare un lungo progetto di studio, di lavoro e di contatto con le api, che ha dato vita nel 2021 ad una serie scultorea ed installativa caratterizzata dalla realizzazione di alveari in ceramica, da calchi di veri favi selvatici.Attualmente, seppure in una costante tensione al sacro ed al divino come fine ultimo, il centro di interesse della mia ricerca si può individuare nella relazione tra la natura e l’ambiente antropizzato. Sono nato e cresciuto a Terni, una città industriale immersa nella regione che viene definita il cuore verde d’Italia. Terni è una linea di confine tra industria e natura,dove le acque del fiume Nera e la potenza della cascata delle Marmore muovono le turbine delle acciaierie da più di cento anni. Basta spostarsi di qualche chilometro dal centro abitato,per addentrarsi nei boschi o salire sulle cime dei monti martani, dove è possibile incontrare i cinghiali, caprioli o anche lupi, come è successo durante delle riprese del video “tra cane e lupo” realizzato a quattro mani con il mio amico, e grande polistrumentista e compositore Rodrigo D’erasmo per la mia personale al CAOS di Terni. Credo che narrare questa linea di confine sia definitivamente il centro del mio interesse e credo che questa sia la chiave per leggere, nel tempo, l’evoluzione del mio lavoro ,secondo una progressiva presa di consapevolezza. Altra presa di consapevolezza sta nell’utilizzo della carpenteria, che da supporto e display espositivo per il mio lavoro ne è diventata progressivamente protagonista in termini sia concettuali che estetici.

Pd’A: Quando lavori ad una mostra che vede più lavori esposti in uno stesso spazio in che tipo di relazione cerchi di metterli fra loro e con lo spazio che li accoglie?

C.C.: Solitamente concepisco una mostra personale come un’opera unica che si sviluppa nello spazio. Lo spazio, sia dal punto di vista architettonico, sia per la sua storia e la sua essenza “animica” è il punto di partenza della mia ricerca per qualsiasi progetto. Quando ho la possibilità di lavorare così, mi piace creare una specie di mondo parallelo in cui possiamo entrare e cambiare prospettiva, oggetti dei nostri pensieri e sganciarci da quello che sta fuori.

Questo è l’obiettivo a cui ambisco quando lavoro nello spazio, provare a trasformarlo in un mondo. Per fare questo ricorro a tutto ciò che può concorrere a stimolare il più possibile i nostri sensi, passando spesso il confine tra la pratica istallativa e quella scenografica. Ho avuto inoltre la fortuna di collaborare, in molti progetti espositivi con grandi musicisti come Rodrigo D’Erasmo, Valerio Vigliar, Alessandro Deflorio. La musica è una componente fondamentale nella gestione dello spazio e nella creazione di mondi. Così l’apporto creativo di questi compositori ha trasformato ogni volta radicalmente la percezione spaziale, costruendo ulteriori livelli istallativi e di conseguenza animici, e riconsegnando al pubblico uno show a due o in alcuni casi un’opera corale, piuttosto che una mostra personale. Sto realizzando in questi giorni, la mia opera permanente per La Serpara, il giardino di sculture di Paul Wiedmer. La serpara è un luogo magico e un’atto di resistenza politica a tutti gli effetti. Paul, Jaqueline, Samuele ed Angela lavorano costantemente per tenere vivo un vero e proprio mondo alternativo, in cui si può vivere ai margini delle logiche del capitalismo sfrenato ed in completa armonia con la natura. Per Paul Wiedmer un artista non deve limitarsi a produrre opere d’arte, ma dovrebbe fornire un modello alternativo di vita. Il mio intervento nello spazio sarà un’opera di carpenteria, una passerella ed un varco che daranno la possibilità a chiunque di sedersi a meditare su di una pietra in mezzo al fiume.

Un altro esempio di lavoro nello spazio, è la mia istallazione permanente “Angelo, Search and Rescue” realizzata per l’Angelo Mai, altro luogo amato e che considero casa. Da un bellissimo confronto con Giorgina P. è nata questa opera con cui abbiamo voluto trasformare visivamente, perché animicamente lo è sempre stato, l’Angelo Mai, in una nave da salvataggio che solca i mari oscuri dei nostri giorni, portando luce.

Pd’A: Puoi raccontare il tuo modus operandi?

C.C.: La scintilla che apre ad un nuovo ciclo di ricerca per me è sempre l’innamoramento per un nuovo materiale e nuove tecniche di lavoro.

Se la costante di fondo è sempre stata la carpenteria ed il ferro, ho attraversato molte fasi di prove,approfondimento, studio, e pratica su diversi materiali come ad esempio la ceramica, il cemento, la galvanica, la fusione in alluminio da calco o la modellazione della cera persa per le fusioni in bronzo. Tutte queste fasi hanno dato vita a periodi produttivi e serie diverse del mio lavoro, non andando però ad esaurirsi o a perdersi nel tempo, ma solitamente a stratificarsi nel mio linguaggio. Nel momento di massimo innamoramento e pratica di un certo materiale arriva anche il match con la ricerca vera e propria, quella più teorica o spirituale per quanto mi riguarda.

Va da se, e succede sempre. È una magia come dicevo prima. Poi questa cosa è molto bella perchè mi permette di entrare in contatto con tanti artisti ed artigiani che portano avanti delle tradizioni che senza di loro andrebbero a perdersi. Nascono legami profondi, amicizie bellissime e io cerco di imparare il più possibile con il massimo dell’umiltà. Poi per quanto riguarda la scultura vera e propria la mia necessità è quella di fare. Entro in officina con delle persone che lavorano con me da tanto tempo, si fa un progetto sommario, ma poi l’opera prende forma mentre la stai facendo. Nascono problemi tecnici e le soluzioni diventano estetica e concetto. Sempre una magia. Che spesso avviene in un luogo magico, un capannone da cui,da più di dieci anni, escono la maggior parte dei miei lavori scultorei. È una magia che abbiamo fatto la prima volta nel 2012 più o meno, con mio zio Graziano, i suoi soci della vecchia Co.i.mont, una carpenteria industriale a Terni ,e con tutti gli operai, ché sono una famiglia meravigliosa per me e da lì ci abbiamo preso gusto. Ormai mi rendo conto di ragionare in funzione di questo luogo, delle macchine che ho la fortuna di poter utilizzare e della bravura delle persone con cui ho la fortuna di lavorare. Quel luogo è una componente fondamentale della mia poetica.

La pittura ha tutta un’altra genesi. Va detto che per un bel po’ di tempo l’ho lasciata un da parte, però poi, quando sono arrivato a studio da Post Ex , la contaminazione con tanti pittori, tutti molto bravi, mi ha fatto riaccendere la fiamma. Adesso dipingo solo quando ho la forte esigenza di manifestare un’immagine , a volte lo faccio in maniera più installativa come ad esempio sui portelloni di un camion, a volte su tela, ma sempre con una vena materica e scultorea di fondo.

Pd’A: Che importanza ha il disegno nel tuo lavoro?

C.C.: La pratica del disegno è diventata per me ormai puramente progettuale. Quando immagino una nuova scultura o una istallazione è sempre la prima cosa che faccio. Disegni molto veloci, ma anche collage o contaminazioni rudimentali con il digitale eccetera . Il disegno è fondamentale per mettere a terra le idee e per immaginare in relazione allo spazio. Disegno molto anche nello studio anatomico, soprattutto degli animali, prima della modellazione di una ceramica o di una cera per la fusione.

Ultimamente però, mi sono trovato, grazie al lavoro per la scenografia dello spettacolo C’era una volta, di Noemi Francesca, con il Teatro Stabile di Napoli, a realizzare un intero libro illustrato ad acquarello e guache. Ho amato molto tutto il progetto di C’era una volta e sono davvero grato a Noemi e a Riccardo Festa, per avere avuto la possibilità di realizzare la mia prima scenografia in teatro. Nel caso del libro, che è parte della scena, e viene proiettato in live a grandi dimensioni, è stato molto bello tornare a disegnare con una accezione illustrativa, concependo il disegno come fine ultimo del processo creativo. E’ stato come tornare un po’ indietro, all’inizio del mio percorso, con una cifra stilistica che ho ripescato un po’ da un libro, dal titolo Burning Hotel, che avevo realizzato nel 2010 con la curatela di Francesco Santaniello per una mostra alla galleria mio Mao di Perugia. Quel libro aveva una prefazione scritta da Vinicio Capossela ed uno stile che aveva molte affinità anche con la sua poetica.

Da allora il mio lavoro e la mia ricerca si sono modificati enormemente ma pensandoci, sarebbe bello recuperare il disegno come pratica, attualizzata ovviamente, ma fine a se stessa.

Pd’A: Quando fai una mostra che tipo di relazione cerchi fra i vari lavori che esponi e il pubblico che viene a vederla?

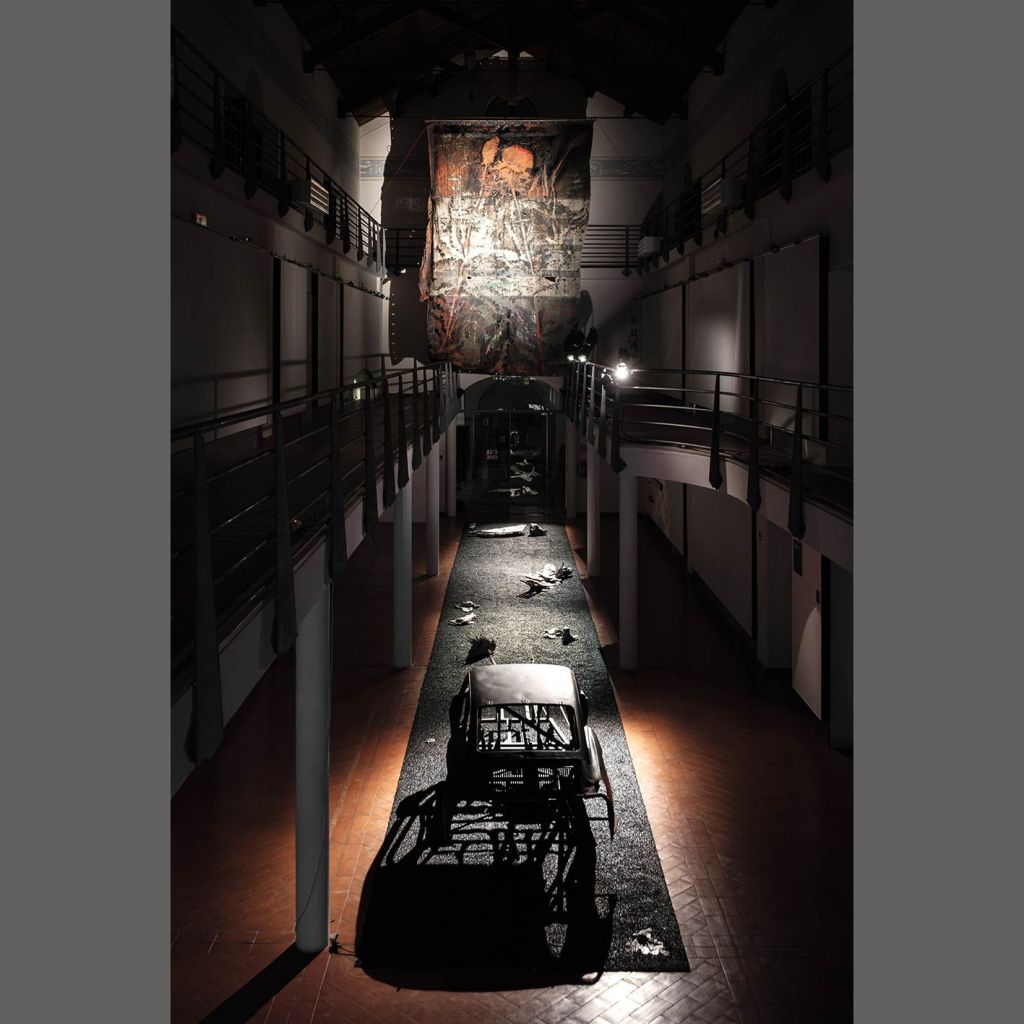

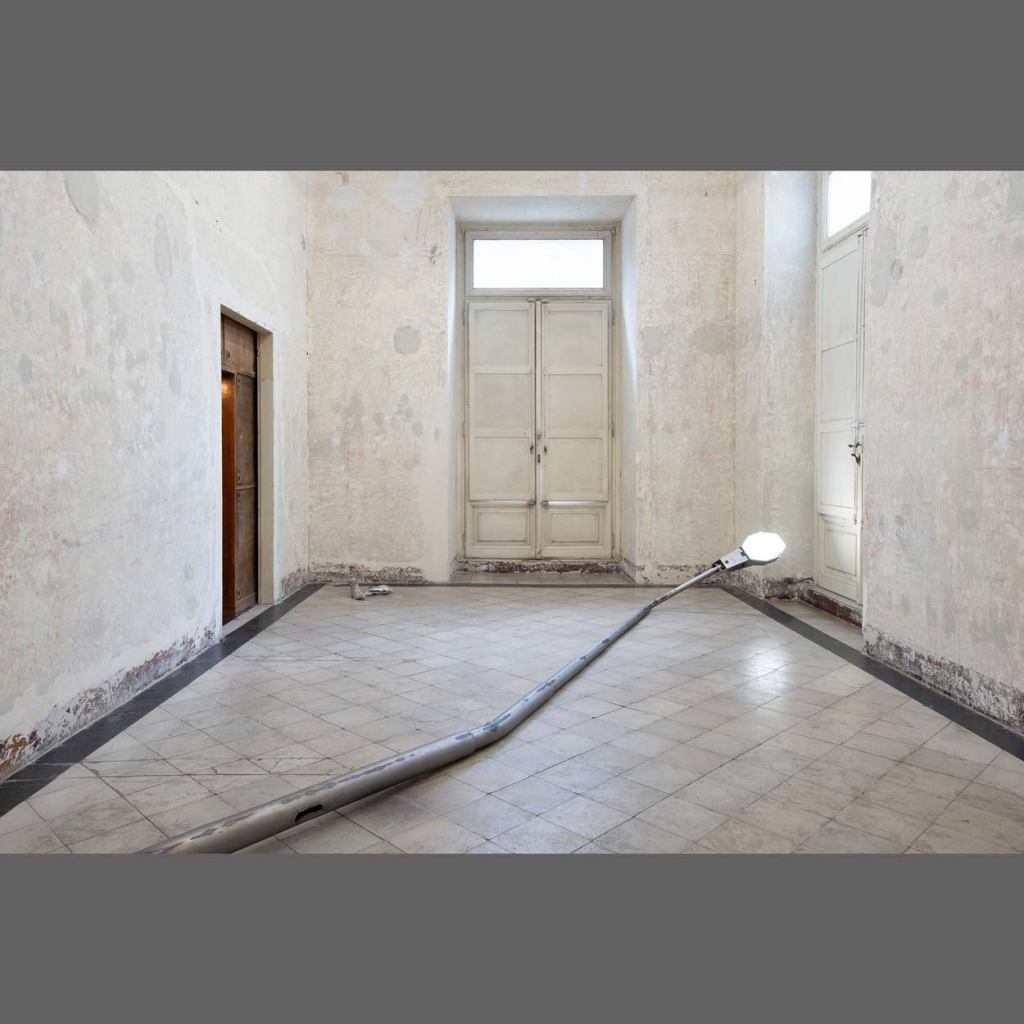

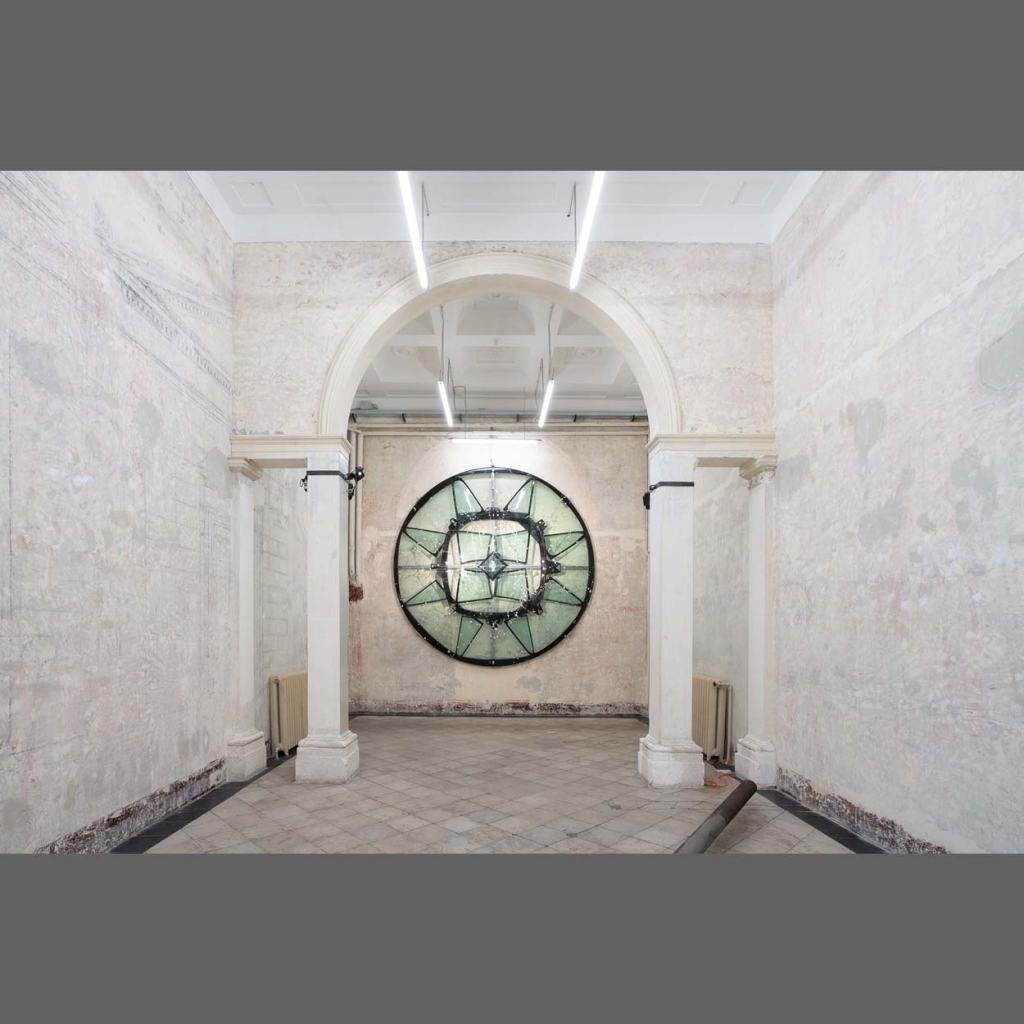

C.C.: Sicuramente cerco di creare un percorso immersivo per il pubblico. Mi piace creare un varco verso un mondo altro, i cui i paradigmi un po’ cambiano. Cioè tipo che tu sei a Roma ad esempio e poi entri in mostra e per quei quindici-venti minuti in cui visiti la ,mostra hai la percezione di essere in un altrove. Ovviamente non parlo di aspetti prettamente scenografici o immersivi nel senso di “Experience” , però mi piace dare allo spettatore dei segnali, dei ganci che lo invitano ad accettare un patto, una specie di gioco anche, nel quale spostiamo un po’ la realtà. A palazzo Brancaccio ad esempio l’idea era di trovarsi a galleggiare in mezzo a relitti spaziali e stradali, provenienti dai nostri giorni. Una sorta di piano astrale, propedeutico allo stato mentale della percezione del silenzio e del vuoto, auto generatosi dopo che il nostro mondo è esploso. Al Museo Caos di Terni, ho creato una strada asfaltata lunga più di dieci metri su cui erano disseminate carcasse di animali in alluminio fuso. Complice il grande lavoro di istallazioni sonore fatto da Alessandro Deflorio e Rodrigo D’Erasmo, percorrendo quella strada si attraversavano diversi passaggi e paesaggi emotivi, tra il cane e il lupo, la luce e l’ombra, la strada e il bosco fino a rivedere le stelle giganti di un cardo dipinto con il catrame sul telone di un camion, salendo al piano superiore del museo.

Pd’A: Una specie di percorso iniziatico?

C.C.: Un rituale di passaggio più che altro, quello iniziatico lo lasciamo agli iniziati appunto.Il percorso iniziatico è un po’ in antitesi sia con il lavo dell’artista che con il “lavoro” del pubblico dell’arte contemporanea. Per l’artista presuppone un distacco da certi demoni che sono tensione fondamentale per far scattare certe scintille. Però sicuramente cerco di creare un varco per attivare

alcune dimensioni e per incontrarci in una sorta di piano astrale condiviso, un luogo all’interno dell’inconscio collettivo.

Pd’A: L’aspetto performativo ti interessa?

C.C.: Non in questo momento della mia ricerca.

Però nel 2023 siamo stati coinvolti con il mio studio, Post Ex, da Giuliana Benassi, in un progetto dal titolo Meta Turismo, per Roma Diffusa, ed ho avuto la possibilità di realizzare un’idea performativa che avevo pensato da tempo. “Raider on the Storm” era il titolo. Io vestito da Rider di Deliveroo con casco integrale e visiera nera, ho trascinato per ore a Campo de Fiori, uno zaino di quelli cubici molto grandi per le consegne, riempito con una zavorra di 80kg. Molto forte, in tutti i sensi per me è stata l’interazione con le persone e la percezione degli stati d’animo che quel raider, perso e stremato in una sorta di via crucis generava. E poi la fatica fisica, il caldo, il sudore sotto il casco, la solitudine che ho provato lì dentro, mi hanno portato in una dimensione con cui è stato “bello” entrare in contatto. Molti non capivano che fosse una performance artistica, provavano un disagio enorme di fronte alla follia apparente di quell’individuo che non rispondeva alle loro domande e continuava a vagare. Altri provavano ad aiutarmi, un inglese ubriaco mi si è parato davanti e voleva picchiarmi. Mi ha dato una testata sul casco. Ci siamo guardati attraverso la visiera per qualche secondo. Mi ha provocato con alcuni insulti. Poi un’altra testata.Io immobile Ho pensato” e ora?” Poi per fortuna si è spostato e mi ha lasciato passare.

CRISTIANO CAROTTI

Terni 1981, Artista Visivo, scultore, pittore, regista cinematografico.

Vive e lavora tra Terni e Roma dove dal 2020, fa parte dell’artist run space Post

Ex, premiato come miglior spazio indipendente Italiano del 2024 dalla rivista

Artribune e segnalato nel 2023 dalla rivista internazionale Frieze, come

protagonista della rinascita della nuova scena artistica italiana.

English text

Interview to Cristiano Carotti

#paroladartista #cristianocarotti #intervistaartista #artistinterview

Pd’A: Hi Cristiano, what importance does the idea of the sacred have in your work?

C.C.: The sacred is the central object of my research.

I would define all my work as a constant Gothic attempt at the sacred. Sculpture is alchemy and magic. During practice, more or less consciously, one finds oneself unwittingly performing rituals, so the tension towards the sacred becomes a necessary condition and state. In making the aluminium casts from casts of animals found run over in the street for example, I found myself performing a very specific ritual.

First the concrete cast, then fire and petrol to clean and disinfect it, finally obtaining a kind of death mask cast in aluminium.

‘Alchemy’, as Eugène Canseliet writes in the preface to Fulcanelli’s ‘The Mystery of the Cathedrals’, “is nothing other than the awakening of life secretly slumbering under the heavy shell of being and the rough bark of things, arising from a certain state of mind very close to real and effective grace. On the two universal planes, where matter and spirit sit together, the process is absolute and consists of a permanent purification to the most complete purification. For this purpose, nothing is more useful, as far as the way to operate is concerned, than the ancient apophthegma, so precise in its imperative conciseness: Salve et coagula; dissolve and coagulate”.

The simple, straightforward technique demands sincerity, decisiveness and patience, and needs imagination, alas!” Will and imagination are the fundamental components for performing magic according to Paracelsus, which is why I believe that every work of art is a magical, and therefore sacred, act.

Like the builders of cathedrals, and as Fulcanelli himself indicates, I like to base my sculptural work on the waste material, the dross of the world, the so-called cornerstone, whether it be the carcass of an animal found in the street, the remains of a car, concrete or the components of an old carpentry workshop. It is the dross that is destined to become alchemical gold.

Pd’A: Has this always been the focus of your interests? How has your work evolved over time?

C.C.: Sacred iconography has always fascinated me. At the beginning of my career, the reinterpretation of certain biblical and Christological images interested me a lot. In 2013, for example, one of my first installations, entitled Goliat, for the +50 exhibition at Spoleto Festival, was a sort of Gothic altar in which the giant’s head was taken from the cab of a TIR, complete with lights and bas-reliefs on the bodywork. Also from those years is a series of sculptural works featuring “black block” or at least protesters in black sweatshirt and hoodie as subjects, related to the Christian iconography of saints. ‘Thirteen’ was the title of an installation at the MLAC in Rome in 2014, with thirteen white plaster fire extinguishers, in reference to Christ and the apostles, and to the fire extinguisher with which Carlo Giuliani was “armed”. Then there was a change in my research, coinciding with my encounter with the thought of Carl Gustav Jung and the exhibition “Dove Sono gli Ultras” in 2016 at White Noise in Rome. On the flags made for that project, in a hybrid between sculpture and painting, various animal figures began to appear, in relation to the archetypes and symbols they embody in ultras culture and in general, in our unconscious.

A fundamental turning point was the encounter with ceramics, which coincided with the covid period and with the recovery, for me, of a lost contact with nature and with my land, Umbria. Ceramics is an ancestral practice and through the study of this medium, the focus shifted decisively to nature, thanks also to the meeting with the artist, ceramist and designer Christopher Domiziani. With Christopher and his company, Domiziani in Torgiano, I have had the good fortune to develop a long project of study, work and contact with bees, which in 2021 gave rise to a sculptural and installation series characterised by the creation of ceramic beehives, from casts of real wild honeycombs.Currently, although in a constant tension with the sacred and the divine as the ultimate goal, the centre of interest of my research can be identified in the relationship between nature and the man-made environment. I was born and grew up in Terni, an industrial city in the region that is called the green heart of Italy. Terni is a borderline between industry and nature, where the waters of the Nera River and the power of the Marmore Falls have been moving the turbines of the steel mills for more than a hundred years. It is enough to move a few kilometres from the town centre, to go into the woods or climb the peaks of the Marmore mountains, where it is possible to encounter wild boar, roe deer or even wolves, as happened during the filming of the video “between dog and wolf” made four-handedly with my friend, and great multi-instrumentalist and composer Rodrigo D’erasmo for my solo exhibition at CAOS in Terni. I believe that narrating this borderline is definitely the centre of my interest and I believe that this is the key to reading, over time, the evolution of my work, according to a progressive awareness. Another realisation lies in the use of carpentry, which has progressively become the protagonist in both conceptual and aesthetic terms from being an exhibition support and display for my work.

Pd’A: When you work on an exhibition where several works are exhibited in the same space, in what kind of relationship do you try to put them in with each other and with the space that hosts them?

C.C.: I usually conceive of a solo exhibition as a single work that develops in space. The space, both architecturally and in terms of its history and “animic” essence, is the starting point of my research for any project. When I have the opportunity to work like this, I like to create a kind of parallel world in which we can enter and change our perspective, objects of our thoughts and disengage ourselves from what is outside.

This is what I aim for when I work in space, to try to turn it into a world. To do this I resort to anything that can help stimulate our senses as much as possible, often crossing the border between installation and scenographic practice. I have also had the good fortune to collaborate in many exhibition projects with great musicians such as Rodrigo D’Erasmo, Valerio Vigliar, Alessandro Deflorio. Music is a fundamental component in the management of space and the creation of worlds.

Thus the creative contribution of these composers has each time radically transformed the spatial perception, constructing further installation and consequently animic levels, and returning to the public a two-man show or in some cases a choral work, rather than a solo exhibition. I am currently creating my permanent work for La Serpara, Paul Wiedmer’s sculpture garden. La Serpara is a magical place and an act of political resistance in its own right. Paul, Jaqueline, Samuele and Angela work constantly to keep alive a real alternative world, where one can live on the edge of the logic of unbridled capitalism and in complete harmony with nature. For Paul Wiedmer, an artist should not only produce works of art, but should provide an alternative model of life. My intervention in the space will be a work of carpentry, a walkway and a passageway that will give anyone the opportunity to sit and meditate on a stone in the middle of the river.

Another example of work in space is my permanent installation “Angelo, Search and Rescue” made for the Angelo Mai, another place I love and consider home. A beautiful confrontation with Giorgina P. gave rise to this work with which we wanted to visually transform the Angelo Mai, because animically it has always been, into a rescue ship that sails the dark seas of our days, bringing light.

Pd’A: Can you tell us about your modus operandi?

C.C.: The spark that opens a new research cycle for me is always falling in love with a new material and new working techniques.

While the basic constant has always been carpentry and iron, I have gone through many phases of testing, in-depth study, and practice on different materials such as ceramics, cement, electroplating, cast aluminium casting, or lost wax modelling for bronze castings. All of these phases have given rise to different production periods and series of my work, but they do not run out or get lost in time, but usually become stratified in my language. In the moment of maximum love and practice of a certain material also comes the match with real research, the more theoretical or spiritual one as far as I am concerned.

It goes without saying, and it always happens. It is magic as I said before. Then this thing is very nice because it allows me to come into contact with so many artists and craftsmen who carry on traditions that would be lost without them. Deep bonds are born, beautiful friendships, and I try to learn as much as I can with the utmost humility. Then as far as the actual sculpture is concerned, my need is to do. I go into the workshop with people who have worked with me for a long time, a rough draft is made, but then the work takes shape while you are making it. Technical problems arise and the solutions become aesthetics and concept. Always magic. That often takes place in a magical place, a shed from which, for more than ten years, most of my sculptural works have come out. It is a magic that we did for the first time in 2012 more or less, with my uncle Graziano, his partners from the old Co.i.mont, an industrial carpentry in Terni, and all the workers, because they are a wonderful family for me, and from there we got a taste for it. By now I realise that I think in terms of this place, the machines I am lucky enough to be able to use and the skill of the people I am lucky enough to work with. That place is a fundamental component of my poetics.

Painting has a different genesis. It has to be said that for quite a while I left it a side, but then, when I arrived at the studio at Post Ex, the contamination with so many painters, all of them very good, rekindled the flame. Now I only paint when I have a strong urge to manifest an image, sometimes I do it in a more installation-like manner, such as on truck doors, sometimes on canvas, but always with an underlying material and sculptural vein.

Pd’A: How important is drawing in your work?

C.C.: The practice of drawing has become purely design-oriented for me. When I imagine a new sculpture or installation, it is always the first thing I do. Very quick drawings, but also collages or rudimentary contaminations with digital and so on. Drawing is fundamental to grounding ideas and imagining in relation to space. I also draw a lot in the anatomical study, especially of animals, before modelling a piece of pottery or wax for casting.

Lately, however, I have found myself, thanks to my work for the set design of the play C’era una volta, by Noemi Francesca, with the Teatro Stabile di Napoli, doing an entire book illustrated in watercolour and gouache. I really loved the whole project of C’era una volta and I am really grateful to Noemi and Riccardo Festa for giving me the opportunity to do my first set design in the theatre. In the case of the book, which is part of the scene, and is projected live in large size, it was very nice to go back to drawing with an illustrative meaning, conceiving drawing as the ultimate goal of the creative process. It was like going back a little bit, to the beginning of my path, with a stylistic approach that I dug out a little from a book, entitled Burning Hotel, that I had done in 2010 with the curatorship of Francesco Santaniello for an exhibition at my Mao Gallery in Perugia. That book had a preface written by Vinicio Capossela and a style that also had many affinities with his poetics.

Since then, my work and research have changed enormously, but thinking about it, it would be nice to recover drawing as a practice, updated of course, but an end in itself.

Pd’A: When you do an exhibition, what kind of relationship do you look for between the various works you exhibit and the public that comes to see it?

C.C.: I definitely try to create an immersive path for the public. I like to create a gateway to another world, whose paradigms change a bit. That is, like you are in Rome, for example, and then you enter an exhibition and for those fifteen to twenty minutes that you visit the ,exhibition you have the perception of being somewhere else. Obviously I am not talking about purely scenographic or immersive aspects in the sense of “Experience”. but I like to give the spectator signals, hooks that invite him to accept a pact, a kind of game even, in which we shift reality a little. In palazzo Brancaccio, for example, the idea was to find ourselves floating amidst space and street wrecks from our own time. A sort of astral plane, preparatory to the mental state of the perception of silence and emptiness, self-generated after our world exploded. At the Museo Caos in Terni, I created a paved road more than ten metres long on which animal carcasses were scattered in molten aluminium. Accompanied by the great work of sound installations by Alessandro Deflorio and Rodrigo D’Erasmo, as you walked along that road you passed through different passages and emotional landscapes, between the dog and the wolf, light and shadow, the road and the forest, until you saw the giant stars of a thistle painted with tar on the tarpaulin of a truck, going up to the upper floor of the museum.

Pd’A: A kind of initiation path?

C.C.: A ritual of passage more than anything else, we leave the initiatory one to the initiates precisely.The initiatory path is somewhat antithetical to both the artist’s work and the ‘work’ of the contemporary art public. For the artist, it presupposes a detachment from certain demons that are fundamental tension in order to set off certain sparks. But I certainly try to create an opening to activate

certain dimensions and to meet in a kind of shared astral plane, a place within the collective unconscious.

Pd’A: Does the performance aspect interest you?

C.C.: Not at this moment in my research.

But in 2023 we were involved with my studio, Post Ex, by Giuliana Benassi, in a project entitled Meta Turismo, for Roma Diffusa, and I had the opportunity to realise a performative idea that I had been thinking about for some time. ‘Raider on the Storm’ was the title. Me, dressed as a Deliveroo Rider with full helmet and black visor, I dragged for hours in Campo de Fiori, a backpack of the very large cubic ones for deliveries, filled with 80kg ballast.

Very strong, in every sense for me, was the interaction with people and the perception of the moods that that raider, lost and exhausted in a sort of via crucis generated. And then the physical fatigue, the heat, the sweat under the helmet, the loneliness I felt in there, took me to a dimension that it was “nice” to come into contact with. Many did not understand that it was an artistic performance, they felt enormous discomfort at the apparent madness of that individual who did not answer their questions and continued to wander. Others were trying to help me, a drunk Englishman stood in front of me and wanted to beat me up. He head-butted me on my helmet. We looked at each other through the visor for a few seconds. He provoked me with some insults. Then another headbutt. I motionless I thought ‘what now?’ Then luckily he moved away and let me pass.

CRISTIANO CAROTTI

Terni 1981, Visual artist, sculptor, painter, film director. Lives and works between Terni and Rome, where since 2020, he has been part of the artist run space Post Ex, awarded as best Italian independent space in 2024 by the magazine Artribune and signalled in 2023 by the international magazine Frieze, as protagonist of the rebirth of the new Italian art scene.

Spazio, il Vuoto su cui tutto giace, 2024, installation view, Palazzo Brancaccio, Contemporary Cluster Roma, a cura di Domenico De Chirico, Foto di Giovanni De Angelis (2)

Spazio, il Vuoto su cui tutto giace, 2024, installation view, Palazzo Brancaccio, Contemporary Cluster Roma, a cura di Domenico De Chirico, Foto di Giovanni De Angelis (4)

Spazio, il Vuoto su cui tutto giace, 2024, installation view, Palazzo Brancaccio, Contemporary Cluster Roma, a cura di Domenico De Chirico, Foto di Giovanni De Angelis

Spazio, il Vuoto su cui tutto giace, 2024, installation view, Palazzo Brancaccio, Contemporary Cluster Roma, a cura di Domenico De Chirico, Foto di Giovanni De Angelis