(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #marcorossetti

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui iniziano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Marco Rossetti: Sì, ma non in modo lineare. Ho iniziato con la pittura, era il linguaggio più immediato per me, il primo strumento con cui ho provato a dare forma a quello che vedevo e sentivo. Poi è arrivata la fotografia, grazie a mio padre, che era un fotografo amatoriale, ma compulsivo. Scattava in continuazione, quasi come se avesse paura di perdere qualcosa. Questo suo archivio di immagini mi ha fatto capire che la memoria non è qualcosa di solido, ma un organismo instabile, che cambia a seconda di chi la guarda e di come la ricompone. Penso che questa consapevolezza mi abbia accompagnato nel tempo, fino a diventare parte centrale del mio lavoro.

Pd’A: Anche tu, come tanti, hai avuto un primo amore artistico?

MR: Forse il primo impatto forte è stato con Giacometti. Quelle figure ridotte all’essenza, consumate dal tempo e dallo spazio, mi sembravano quasi frammenti di memoria sospesi tra presenza e assenza. Ma se penso a un amore più profondo, allora direi Franco Vaccari. Il suo modo di lavorare con l’immagine, il concetto di “esposizione in tempo reale”, mi ha aperto una strada diversa, meno legata all’oggetto artistico e più alla traccia, al processo. Mi affascina l’idea che l’arte possa essere qualcosa che accade, che non si fissa in una forma definitiva, ma continua a trasformarsi con il tempo e con lo sguardo di chi la attraversa.

Pd’A: Che idea hai della natura?

MR: Non la vedo come qualcosa di separato da noi. Il problema sta proprio nel modo in cui la cultura occidentale ha creato questa frattura tra umano e naturale. La natura non è un’entità romantica o idilliaca, è un sistema di connessioni e scambi di energia di cui facciamo parte. Nel mio lavoro cerco di esplorare questo rapporto ibrido, che oggi è sempre più contaminato dalla tecnologia e dall’alterazione dei processi biologici.

Pd’A: Che importanza ha nel tuo lavoro l’idea di memoria?

MR: Fondamentale. La memoria non è solo qualcosa che riguarda il passato, ma una forza attiva che continua a riconfigurarsi nel presente. Lavoro spesso con materiali che portano con sé un carico di tempo, come le fotografie d’archivio, ma anche con dispositivi meccanici che creano una sorta di loop, ripetendo azioni o immagini come se tentassero di ricostruire qualcosa che sfugge. La memoria è un processo di costruzione e perdita al tempo stesso, e questo paradosso mi interessa molto.

Pd’A: Che importanza hanno le categorie di tempo e spazio nel tuo lavoro?

MR: Sono la base di tutto. Tempo e spazio nel mio lavoro non sono lineari o fissi, ma fluttuano, si sovrappongono, si deformano. L’idea del tempo che si sgretola, che non è più qualcosa di cronologico ma un insieme di frammenti che si sovrappongono e si cancellano, è qualcosa che cerco di tradurre nelle mie installazioni. Lo spazio, invece, è sempre un campo di tensione, un luogo che si attiva attraverso il movimento e le relazioni tra gli elementi.

Pd’A: Spesso nei tuoi lavori compare una dimensione “rudimentale tecnologica” che introduce l’idea di movimento quasi organico. Puoi raccontare come sei arrivato a queste soluzioni e quali idee chiamano in causa all’interno del tuo lavoro?

MR: Mi interessa la tecnologia quando non è perfetta, quando ha una sorta di fragilità o di resistenza. Uso spesso meccanismi semplici, a volte quasi obsoleti, che creano movimenti minimi, ripetitivi, mai del tutto controllabili. Questi movimenti generano un senso di attesa, di sospensione, come se l’opera fosse sempre sul punto di rivelare qualcosa. È un modo per evocare la presenza dell’assenza, qualcosa che cerca di ricomporsi ma non può farlo del tutto.

Pd’A: Secondo te le opere d’arte esistono se non c’è nessuno che le guarda?

MR: L’opera esiste sempre, anche senza un osservatore, ma la sua attivazione avviene nello sguardo. Un’opera chiusa in un archivio o dimenticata in un deposito non smette di essere, ma è come un seme che aspetta il terreno giusto per germogliare. La relazione con chi guarda è ciò che le permette di trasformarsi, di generare senso.

Pd’A: Quando devi fare una mostra ti interessa l’idea di messa in scena del lavoro?

MR: Molto. Non penso mai a un’opera come a qualcosa di isolato, ma a un sistema di relazioni che si attivano nello spazio. Il modo in cui un lavoro è collocato, la luce, il ritmo con cui il pubblico si muove tra le opere… tutto questo fa parte dell’esperienza. È una costruzione che può avvicinarsi all’idea di una coreografia, in cui ogni elemento ha un peso specifico.

Pd’A: Che importanza ha la relazione che si viene a creare fra i vari lavori che decidi di esporre insieme?

MR: È fondamentale. Una mostra per me non è mai una semplice somma di opere, ma un organismo che si struttura in base alle connessioni tra le diverse parti. A volte queste relazioni emergono in modo intuitivo, altre volte attraverso contrasti. In ogni caso, cerco di costruire un’esperienza che abbia una tensione, qualcosa che spinga chi guarda a muoversi nello spazio con uno sguardo attivo.

Pd’A: Che idea hai della bellezza?

MR: Non mi interessa la bellezza intesa in senso classico, come armonia o proporzione. Per me la bellezza è qualcosa di più complesso, qualcosa che può essere anche disturbante, incompleto, fragile. È ciò che trattiene lo sguardo, che ci costringe a rimanere in una situazione di incertezza o di apertura.

Pd’A: Qual è la sua posizione rispetto al suo lavoro?

MR: Il mio lavoro è un continuo interrogarsi, un modo per esplorare delle domande più che per dare risposte. Non mi interessa un’arte che semplifica, ma che crei tensione che apra spazi di possibilità. Mi piace pensare alle opere come a dispositivi di attivazione, che non si esauriscono in una sola lettura ma continuano a generare senso nel tempo, a seconda di chi le guarda e del contesto in cui si trovano.

Marco Rossetti è artista visivo diplomato in Pittura presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli nel 2011. Ha all’attivo una serie di mostre personali, tra le quali: “Sistemi di memoria stabile” (2024) presso la Chiesa della Ss. Annunziata di Polla (SA), “Come una stella di giorno” (2021) alla Galleria Nicola Pedana di Caserta, “Bias” (2020) presso lo Studio DeVITALAUDATI a Firenze e “Slander” (2017) alla BRAU – Biblioteca di Ricerca di Area Umanistica a Napoli. Le sue opere sono state esposte anche in mostre collettive, tra cui “L’Abisse visage” (2024) alla Galleria Muryow di Toyama in Giappone, “Così è. La stirpe delle foglie” (2024) allo Spazio Contemporanea a Brescia. “Punti d’incontro” (2022) presso Casermetta di Santa Croce a Lucca, “Fotogenesi” (2022) allo spazio Habitat 83 di Verona, “ICONOSMASH” (2019) a Palazzo Rinuccini di Firenze e “V.Ar.Co (2019) presso l’Università degli Studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” a Napoli. Rossetti ha partecipato a diverse residenze artistiche, tra cui “Falìa” (2018) a Lozio, Val Camonica e il “ProgettoBorca” (2017) a Borca di Cadore. Nel 2021 è stato vincitore del premio Level 0 al Museo Madre, del Premio De Buris e dell’Art Tracker. Finalista al Talent Prize nel 2023, è stato il vincitore di Un’opera per il Castello a Castel Sant’Elmo a Napoli (2018). Ha anche ricevuto riconoscimenti al Premio Smart Up Optima e al Premio Fabbri. Ha partecipato alle fiere Miart e ArteFiera Bologna. Attualmente Marco Rossetti vive e lavora a Firenze.

English text

Interview to Marco Rossetti

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #marcorossetti

Parola d’Artista: For most artists, childhood is the golden age when the first symptoms of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Marco Rossetti: Yes, but not in a linear way. I started with painting, it was the most immediate language for me, the first tool with which I tried to give form to what I saw and felt. Then came photography, thanks to my father, who was an amateur but compulsive photographer. He took pictures all the time, almost as if he was afraid of losing something. This archive of images of his made me realise that memory is not something solid, but an unstable organism, which changes depending on who is looking at it and how they recompose it. I think this awareness has accompanied me over time, until it has become a central part of my work.

Pd’A: Did you, like many, have a first artistic love?

MR: Perhaps the first strong impact was with Giacometti. Those figures reduced to their essence, consumed by time and space, seemed to me almost like fragments of memory suspended between presence and absence. But if I think of a deeper love, then I would say Franco Vaccari. His way of working with the image, the concept of ‘exposure in real time’, opened up a different path for me, less tied to the artistic object and more to the trace, to the process. I am fascinated by the idea that art can be something that happens, that is not fixed in a definitive form, but continues to transform with time and the gaze of those who pass through it.

Pd’A: What is your idea of nature?

MR: I don’t see it as something separate from us. The problem lies in the way Western culture has created this divide between human and natural. Nature is not a romantic or idyllic entity, it is a system of connections and energy exchanges that we are part of. In my work I try to explore this hybrid relationship, which today is increasingly contaminated by technology and the alteration of biological processes.

Pd’A: How important is the idea of memory in your work?

MR: Fundamental. Memory is not just something that concerns the past, but an active force that continues to reconfigure itself in the present. I often work with materials that carry a load of time, such as archive photographs, but also with mechanical devices that create a sort of loop, repeating actions or images as if trying to reconstruct something that escapes. Memory is a process of construction and loss at the same time, and this paradox interests me greatly.

Pd’A: How important are the categories of time and space in your work?

MR: They are the basis of everything. Time and space in my work are not linear or fixed, but fluctuate, overlap, deform. The idea of time crumbling, which is no longer something chronological but a collection of fragments that overlap and erase, is something I try to translate into my installations. Space, on the other hand, is always a field of tension, a place that is activated through movement and the relationships between elements.

Pd’A: A ‘rudimentary technological’ dimension often appears in your work, introducing the idea of almost organic movement. Can you tell us how you arrived at these solutions and what ideas they bring into your work?

MR: I am interested in technology when it is not perfect, when it has a kind of fragility or resistance. I often use simple, sometimes almost obsolete mechanisms that create minimal, repetitive movements that are never entirely controllable. These movements generate a sense of waiting, of suspension, as if the work were always on the verge of revealing something. It is a way of evoking the presence of absence, something that tries to recompose itself but cannot fully do so.

Pd’A: Do you think works of art exist if there is nobody looking at them?

MR: The work always exists, even without an observer, but its activation occurs in the gaze. A work closed in an archive or forgotten in a warehouse does not cease to be, but is like a seed waiting for the right soil to germinate. The relationship with the beholder is what allows it to transform, to generate meaning.

Pd’A: When you have to make an exhibition, are you interested in the idea of staging the work?

MR: Very much. I never think of a work as something isolated, but as a system of relationships that are activated in the space. The way a work is placed, the light, the rhythm with which the audience moves between the works… all this is part of the experience. It is a construction that can come close to the idea of a choreography, in which each element has a specific weight.

Pd’A: How important is the relationship that is created between the various works that you decide to exhibit together?

MR: It’s fundamental. An exhibition for me is never a simple sum of works, but an organism that is structured according to the connections between the different parts. Sometimes these relationships emerge intuitively, other times through contrasts. In any case, I try to construct an experience that has a tension, something that prompts the viewer to move through the space with an active gaze.

Pd’A: What is your idea of beauty?

MR: I am not interested in beauty in the classical sense, as harmony or proportion. For me beauty is something more complex, something that can also be disturbing, incomplete, fragile. It is what holds our gaze, what forces us to remain in a situation of uncertainty or openness.

Pd’A: What is your position on your work?

MR: My work is a continuous questioning, a way of exploring questions rather than giving answers. I am not interested in art that simplifies, but in creating tension that opens up spaces of possibility. I like to think of works as activating devices, which are not exhausted in a single reading but continue to generate meaning over time, depending on who is looking at them and the context in which they are located.

Marco Rossetti is a visual artist who graduated in Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples in 2011. He has to his credit a series of solo exhibitions, including ‘Stable Memory Systems’ (2024) at the Church of the Ss. Annunziata in Polla (SA), ‘Come una daytime star’ (2021) at the Galleria Nicola Pedana in Caserta, “Bias” (2020) at Studio DeVITALAUDATI in Florence and ‘Slander’ (2017) at the BRAU – Research Library of the Humanities Area in Naples. The his works have also been exhibited in group exhibitions, including ‘L’Abisse visage’ (2024) at the Muryow Gallery in Toyama, Japan,’Thus it is. La stirpe delle foglie’ (2024) at Spazio Contemporanea in Brescia. ‘Punti d’incontro’ (2022) at Casermetta di Santa Croce in Lucca, ‘Fotogenesi’ (2022) at Spazio Habitat 83 in Verona, ‘ICONOSMASH’ (2019) at Palazzo Rinuccini in Florence and ’V.Ar.Co’ (2019) at the Università degli Studi della Campania ‘Luigi Vanvitelli’ in Naples. Rossetti has participated in several artistic residencies, including ‘Falìa’ (2018) in Lozio, Val Camonica and the ‘ProgettoBorca’ (2017) in Borca di Cadore. In 2021 he was the winner of the Level 0 at the Museo Madre, the De Buris Prize and the Art Tracker. A finalist for the Talent Prize in 2023, he was the winner of Un’opera per the Castle at Castel Sant’Elmo in Naples (2018). He also received awards at the Smart Up Optima Prize and the Fabbri Prize. He has participated in the Miart and ArteFiera Bologna fairs. Currently living and working in Firenze.

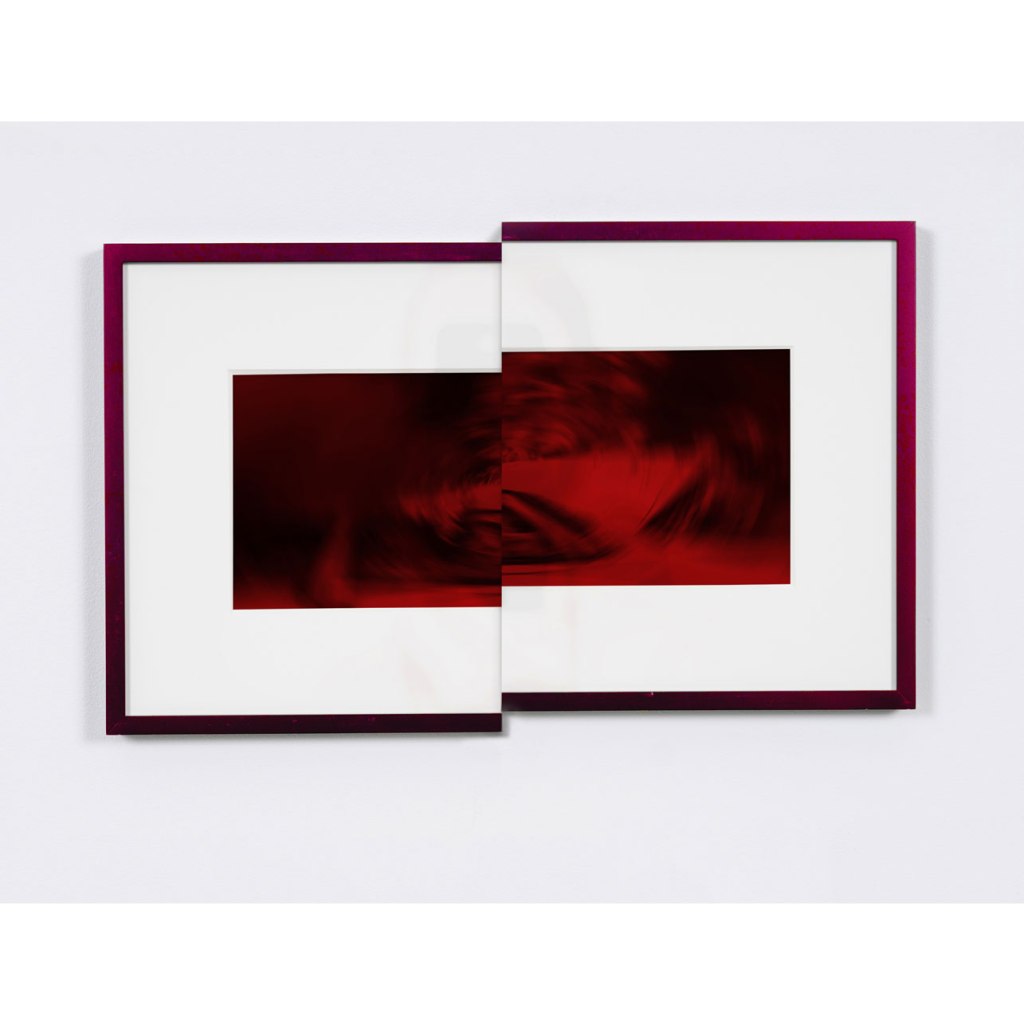

multimediale (tergicristalli con motori, stampa di foto

d’archivio su carta, legno, vetro), dimensioni variabili.

(legno, vetro, fornelli elettrici, stampa di foto d’archivio su

carta, cera d’api, paraffina), dimensioni variabili