(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #mauriziodonzelli #artistinterview #intervistaartista

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Maurizio, che valore ha per te il disegno?

Maurizio Donzelli: “Il braccio si appoggia al tavolo, il polso e il palmo della mano leggermente sulla carta, ma io non mi accorgo della mano né del polso. A cosa tento di pensare? Lo sforzo è di non pensare. A cosa servirebbe il pensiero se non a procurarmi un’ennesima forma di distrazione?”.1

Scrivevo così in un mio testo del 2012. Ho spesso parlato del disegno e soprattutto del disegnatore, una sorta di figura emblematica, ma anche una vera e propria esperienza di pedagogia e di formazione. 2

Il disegno in questo caso non è il bozzetto, la didascalia, il progetto, lo schizzo, il grafico ecc. Il disegno è soprattutto “l’inizio”, è uno stato di concentrazione che dà all’immagine la possibilità di apparire davanti ai nostri occhi, che dà all’artista la possibilità di esplorare, anche passivamente, qualche cosa di nuovo attraverso sé.

Il pensiero razionale e la didascalia ci riconducono nella reiterazione dell’esperienza e del risaputo, nel mondo sensibile delle cose che vedo e riconosco.

Mentre l’inizio del disegno mette al mondo anche ciò che noi non sappiamo di noi stessi, la novità della scopertael’analogia tra le cose, che sono gli elementi più interessanti sia dell’opera sia dell’esperienza artistica.

Il disegno non deve essere replica mimetica, perché non deve esaurirsi nella letteralità del linguaggio.

Per questo lo sforzo principale del disegnatore è la ricerca di uno stato di concentrazione e di assenza. Corpo e mente non sono mai separati e noi artisti abbiamo la piccola gioia di poter usare le mani oltre che gli occhi. Non si tratta d’improvvisazione però, è il materiale dell’artista che mette al mondo l’artista stesso.

1. Maurizio Donzelli, “Il Presente”, in Metamorfosi, catalogo della mostra realizzata a Palazzo Fortuny, Venezia. Milano, Mousse Publishing, 2012.

2 -Negli anni passati ho realizzato delle performance chiamate Macchina Dei Disegni, poi ho anche condotto 3 seminari a numero chiuso, in 3 anni diversi, presso il Museo di Santa Giulia di Brescia, concentrati proprio sul tema del disegno; non erano diretti agli studenti delle accademie, io tenevo partecipassero anche persone comuni, persone appassionate.

Pd’A: Il disegno è dunque per te un metodo di indagine, uno strumento di conoscenza per sondare le diverse possibilità dell’esistenza?

MD: Non si può delegare la conoscenza ai soli principi razionali, il rapporto causa-effetto non funziona in tutti i campi dell’umano; il rischio principale è l’ottundimento e l’anestesia dei valori di cui vediamo il dilagare nelle nostre società. Ma già nella fisica quantistica questi principi sono messi in dubbio, e così anche in molti altri campi della scienza dove non si esclude il coinvolgimento della nostra coscienza nel processo di percezione della realtà.

L’arte resiste a ogni sistematicità, non è indifferenziata e questo per noi ha anche un valore pratico. L’arte ci parla della nostra esistenza dando molte risposte ma ancor di più ponendo domande. Il suo modello ha poco a che vedere con la causalità scientifica, non si misura, ma si può solo condividere; è un modello empirico, dichiaratamente fragile, è uno strumento che prevede una serie di personalissimi processi che hanno come inizio e come fine la nostra coscienza. Altrimenti non ci resta che iniziare a misurare l’intuizione, le analogie tra le cose, i sentimenti, la bellezza, la poesia, la musica, le emozioni, ecc.

Pd’A: Nel tuo lavoro spesso si crea una intensa relazione con lo spazio in cui intervieni in che modo avviene?

MD: Non credo che nessuna opera d’arte rimanga indifferente rispetto allo spazio in cui è collocata. Esistono dei display apparentemente neutri, per esempio il white cube, certi stand fieristici, ma questo modo di esporre è anche una sorta di ideologia: ordine, ritmo, scansione 1-zero-1. Nel white cube è come se sfogliassimo le pagine di un libro, dove spesso le opere sono disposte per dimensione o per modelli cronologici o di materiali: tele, grafiche, documentazione fotografica, ecc. Con la nostra odierna mentalità immaginiamo di visitare un’esposizione dei Salon Des Artistes Indipendants sul finire dell’800, saremmo davvero in difficoltà!

Se pensiamo ai grandi palazzi del passato, ai loro saloni, alle monumentali architetture, ai pavimenti, alle decorazioni, agli arredi, noteremo che le opere d’arte erano inserite in relazione a quegli ambienti. Spesso le opere si sovrapponevano nel tempo con interventi successivi, contrasti di epoche e gusti differenti si stratificavano mano a mano, niente poteva rimanere isolato dal contesto. La nostra continua ossessione ad isolare mette in luce alcune tipiche caratteristiche della nostra modernità.

Da qui nasce anche una domanda sul concetto di autonomia dell’opera e soprattutto al ruolo sociale dato all’artista: condizionato dalla mitologia totemica dell’autore, come soggetto dall’attitudine e dal temperamento individualistico, isolato nel recinto delle proprie personalissime esperienze.

Non nego l’autonomia dell’autore e dell’opera, non nego che l’uno e l’altra siano stretti da un vincolo irriducibile, ma entrambi sono anche inseriti in un flusso della storia che ne determinano il risultato. Questo accade anche all’insaputa dell’autore, proprio perché nulla di quello che realizziamo è slegato da un processo storico, e tale processo è profondamente nutrito dal passato, da ciò che ci ha preceduto.

Credo che la stessa opera appoggiata su un muro bianco o su un muro affrescato diventi differente. Non si tratta di cornice, si tratta di contaminazioni, di accumuli di storia, di un processo d’inglobamento che rimette in gioco anche il senso di quello che viene mostrato; perché il contesto può dare differenti risultati e differenti interferenze. Io cerco molto questi contrasti o queste simmetrie. L’opera è solo apparentemente un frammento, e se lo vogliamo definire in questo modo dobbiamo assolutamente immettere questo frammento all’interno di quel fluido continuo che è la Storia, un flusso – passato/futuro – che qualche volta può essere interrotto collocando lo spettatore in un rinnovato presente.

Pd’A: La tua risposta apre un nuovo fronte, che mi sembra intimamente legato allo spazio, quello del tempo. Mi sembra che nella tua opera coesistano una pluralità di tempi ?

MD: Nella letteratura, nella musica, nel cinema, si percepisce una freccia del tempo, scivoliamo dentro queste opere man mano; esiste un inizio, uno svolgimento e una conclusione. Di fronte a un quadro o a una scultura la questione del tempo si presenta in una maniera differente.

A noi spettatori si richiede una sorta di passività, un’attenzione che non è generata da alcun “moto” dell’oggetto visionato, in apparenza è tutto lì davanti a noi, non ci chiediamo:

“E adesso cosa farà? – E adesso cosa succederà?”

Restiamo di solito immobili, magari anche solo per qualche istante, a fissare un quadro, questo tempo che passa non è un “tempo-cronologico” come quello degli orologi, è un “tempo-momentaneo”, legato al corpo e al pensiero, ha un intervallo differente e soprattutto non è misurabile. (1)

Dal 2002 realizzo una particolare serie di opere che intitolo invariabilmente Mirror. I Mirrors, per un effetto ottico prodotto da una lente prismatica, producono una sorta di sdoppiamento e sovrapposizione dell’immagine; questo sdoppiamento però avviene durante il movimento dello spettatore di fronte al quadro; è il contrario dell’ologramma o della prospettiva rinascimentale, dove lo spettatore è programmaticamente obbligato a una posizione precisa nello spazio.

Per esempio osservando un Mirror tre persone vicine vedono tre differenti immagini dello stesso quadro, si tratta certamente di piccole variazioni, ma tanto basta per trasformare questo meccanismo visivo in una vera e propria metafora: ognuno, dal proprio punto di vista, interpreta ciò che vede in maniera differente.

L’oggettività dell’interpretazione è solo una nostra congettura, una tesi, un’Idra dalle molte facce che non produce significati prevalenti; io stesso che sono l’autore del Mirrors non posso dire quale sia il modo e la posizione più corretta per osservarli.

Questa perdita di controllo è per me anche uno stimolo molto interessante: non domino completamente il materiale del mio lavoro ma vengo da esso sollecitato all’esperienza e alla scoperta.

(1) Di certo nelle arti visive le questioni sono molto più complicate di così, basti pensare alla scultura o alle installazioni ambientali ecc. Le performance hanno più freccia del tempo: inizio/fine.

Pd’A: Il colore?

MD: Questa del colore è una libertà, decido di volta in volta, se non serve non lo uso, se serve lo uso. Studio anche le palette di colori di tanti artisti che amo. Dentro al colore respiriamo, mi basta questo, non abbiamo più bisogno di giustificazioni. Credo che il tabù cromofobico stia lentamente scomparendo, chi l’ha compreso bene, gli altri si aggiornino! Il colorato non è più sinonimo di contaminato, mano a mano entriamo nel XXI secolo ci sentiamo più liberi da questo novecentesco pregiudizio ideologico. Il colore è stato considerato dai suoi detrattori come infantile o volgare: l’impuro contro la purezza assoluta del monocromo ecc. Stesse obiezioni sono state fatte all’ornamentale anche se in modi e misure differenti.

Si potrebbe approfondire e ne varrebbe davvero la pena sarebbe un discorso interessante.

A me sembrano però questioni davvero superate che magari vale la pena di leggere sotto il profilo storico, sociologico, raccontano molto di noi.

Varrebbe ancor di più considerarle sotto il profilo della logica, e della filosofia del linguaggio, per esempio le fondamentali considerazioni di Wittgenstein sul colore, o il libro di Derek Jarman Chroma o il belllissimo libretto di David Batchelor intitolato Cromofobia.

Pd’A: Maurizio che rapporto cerchi di stabilire con chi guarda i tuoi lavori?

MD: << I quadri li fanno quelli che li guardano>>.

La frase di Duchamp è tanto celebre che forse nel tempo si è anche un po’ sciupata.

L’autore, l’opera, il pubblico, tre figure distinte ma inseparabili.

Guardare nella solitudine del proprio studio un lavoro appena concluso o guardarlo insieme a un’altra persona porta a distinte sollecitazioni: l’opera in un certo senso cambia di significato.

Nell’etimologia “mostrare” è un verbo transitivo: mostrare, sottoporre alla vista, far vedere, additare, ma la sua radice latina deriva da monstru(m) chesignifica anche prodigio, segno (divino).

Credo che la partecipazione dello spettatore sia un elemento fondamentale forse perché la visione prevede anche “il prodigio”. L’artista è soltanto il primo spettatore di uno spettacolo ancora incompleto.

Prendiamo come contro-esempio le immagini della comunicazione, per essere efficaci devono essere dirette, o magari anche indirette, ma inequivocabili. Queste immagini devono sforzarsi di ridurre l’elemento sviante insito nell’immagine riprodotta per raggiungere il proprio fine: la vendita di un bene.

Ma ancor più importante è l’adesione di questo processo a una concezione della realtà tanto cara alla nostra ragione che si chiama principio d’identità: ogni cosa è uguale a se stessa (A=A).

Lo stesso vale nell’immagine didascalica, nel progetto, nel rendering, nella qualità dei dettagli sta l’efficacia del risultato che è direttamente proporzionato alla corretta descrizione, all’adesione dell’immagine all’oggetto descritto; il risultato finale però è un’illustrazione, un artificio, una didascalia; più descrive, più aderisce alla cosa in sé, meglio raggiunge il proprio scopo.

Sul fronte opposto si trova “l’immagine aperta”, capace di far risonare nell’osservatore degli elementi sconosciuti, di indurlo a produrre delle analogie, una cascata di latenze, di ulteriori rimandi dove (A=A) ma anche (A = B = C ~ ∞).

Tengo molto al concetto di immagine come elemento di Risonanza, un risonatore che prevede lo spettatore.

Questo movimento dell’immagine verso l’osservatore e dell’osservatore verso l’immagine rende vitale il rapporto tra osservatore e oggetto osservato, entrambi diventano i necessari equilibratori di senso.

Idealmente questo moto non dovrebbe mai concludersi, dovrebbe restare sempre nel regno del “quasi” sempre oscillante e sospeso, immagine viva: prodigio e sollecitazione.

Pd’A: L’esercitare la ripetizione, non seriale del segno, ti avvicini ad una dimensione spirituale?

MD: Come scrivi tu la ripetizione non è nel mio caso un elemento seriale programmatico.

Mi avvicino alla ripetizione più come a qualcosa legato a una ossessione: l’ossessione per una immagine, per un pattern, per delle particolari forme o colori. Non mi dispiace, una volta ottenuto un risultato interessante, essere ulteriormente tentato di ripeterlo, un po’ anche perché l’immagine migliora di volta in volta, ma questo fa parte del mestiere..

Quanto può durare questa ripetizione? Evidentemente non c’è nessuna regola, mi sono accorto che però resto prigioniero per un periodo imprecisabile di queste mie immagini. Con il tempo ho imparato che è inutile opporsi ad esse, esse mi educano, si fanno riconoscere, fanno parte di me ma soprattutto sento che hanno una loro propria autonomia.

Posto il problema in questa maniera –il gesto- e la sua ripetizione ti permettono la grande libertà di lavorare senza pensare, cioè –“di veder accadere” – davanti ai tuoi occhi l’immagine nel suo svolgimento. Ma si tratta di un equilibrio tra la tua volontà e la tua passività, è un interessante esercizio in cui l’immagine ti fa sentire di essere in risonanza con il resto della realtà.

I momenti migliori sono quelli in cui al chiuso del tuo studio il processo avviene con facilità, in maniera naturale, senza sforzo, in questi casi tutto sembra aver senso; ma purtroppo questo non avviene di frequente. Non so se quanto detto ha a che vedere con la spiritualità, credo forse che abbia per certi aspetti a che fare con la preghiera e con il silenzio; quella “necessità di silenzio” che come dice Rilke sta intorno a tutte le cose.

Pd’A: Maurizio senti ho visto che ultimamente fai dei lavori con la tecnica del ricamo li realizzi tu o li fai fare? Come procedi in questo lavoro?

MD: In realtà sono degli arazzi che faccio realizzare in Belgio usando la tecnica del telaio Jacquard, che è un particolare telaio che automatizza i singoli fili dell’ordito; il telaio Jacquard è un tipo di telaio inventato e perfezionato ancora nel XIX secolo.

Questa evoluzione della tessitura mi permette un relativo controllo del progetto e un costo più contenuto, anche se purtroppo gli arazzi sono notevolmente impegnativi sul piano economico e di produzione. Potrei parlare a lungo degli arazzi, anzitutto citare il fascino di quei colori polverosi che assorbono e riflettono la luce come nessun altro materiale; poi perché questa tecnica mi da la possibilità di sviluppare idee che partono sia dalle mie immagini sia da un’elaborazione di frammenti di arazzi antichi.

Nonostante tutti i passaggi tecnologici il metodo è sempre uguale: un tempo l’artista preparava il bozzetto o il disegno base e lo passava all’arazziere che nella propria manifattura lo trasformava in arazzo; oggi accade ancora lo stesso, con l’avvento delle macchine a controllo numerico tutto il processo viene digitalizzato, ma questo non toglie che dietro a ogni produzione ci sia un grande lavoro di sapienza artigianale e di stretto contatto tra gli artigiani e l’artista.

L’arazzeria antica, perlomeno quella che amo di più, inizia nel Medioevo e arriva fino alle soglie del Rinascimento, ha in primo luogo un carattere fortemente ornamentale, ma anche onirico ed enigmatico; la struttura narrativa è quasi fiabesca, gli alberi, il fogliame, le posture dei personaggi, l’ambientazione in generale hanno uno stile anti-realistico e molto simbolico.

Da un certo punto in avanti l’arazzo medioevale comincia a dover competere con le innovazioni della pittura. L’invenzione del colore a olio e delle velature, il realismo della prospettiva, l’attenzione alle ombre e ai particolari pittorici, mettono in crisi il mondo degli arazzi, perché questa tecnica non riesce a superare in qualità la pittura, soprattutto l’affresco che per dimensioni è un diretto competitore. Faccio solo un esempio: per quanto enormi e sontuosi gli arazzi di Raffaello sono meno interessanti dei suoi stessi cartoni preparatori.

L’ultimo grande autore che di certo chiude un’epoca è Bartolomeo Suardi detto il Bramantino con il suo ciclo milanese degli arazzi Trivulzio. In questo ciclo vediamo ancora degli aspetti di rappresentazione tardo medioevale mescolati a concetti e invenzioni rinascimentali, molti frammenti costitutivi dei miei arazzi vengono da questa serie di arazzi.

Capisco di essermi un po’ dilungato nella risposta ma questa premessa è necessaria per descrivere un approccio di lavoro. Da questi presupposti e da queste fascinazioni nascono le mie elaborazioni successive, immagini dove frammenti mescolati diventano palindromi e a volte ulteriormente specchiati. Io credo che sia inutile o addirittura dannoso cercare di descrivere il contenuto delle mie immagini, anzi uno dei motivi che mi spingono a mettere in produzione un arazzo è proprio quando vi riconosco qualcosa di interessante ma di sconosciuto, una immagine che non riesco a comprendere ma soltanto sentire, una immagine ugualmente vicina e lontana.

English text

Interview to MAURIZIO DONZELLI

#paroladartista #mauriziodonzelli #artistinterview #intervistaartista

Parola d’Artista: Hi Maurizio, what value does the drawing have for you?

Maurizio Donzelli: ‘The arm rests on the table, the wrist and palm lightly on the paper, but I do not notice the hand or the wrist. What do I do I try to think? The effort is not to think. What would be the use of thinking if if not to provide me with yet another form of distraction? ‘

1 I wrote so in a text I wrote in 2012. I have often spoken of drawing and especially of the draughtsman, a kind of emblematic figure, but also a real pedagogical and training experience.

2 The drawing in this case is not the sketch, the caption, the sketch, the graphic, etc. Drawing is above all ‘the beginning’, is a state of concentration that gives the image the possibility of appearing before our eyes, which gives the artist the opportunity to explore even passively, something new through himself.

The rational thought and caption lead us back into the reiteration of experience and the known, in the sensitive world of things I see and recognise. While the beginning of drawing also brings into the world what we do not know about ourselves, the novelty of discovery and the analogy

between things, which are the most interesting elements of both the work and of the artistic experience.

The drawing must not be mimetic replication, because it must not exhaust itself in the

literalness of language. For this the main effort of the draughtsman is the search for a state of concentration and 1. Maurizio Donzelli, ‘Il Presente’, in Metamorfosi, catalogue of the exhibition held at Palazzo Fortuny, Venice. Milan, Mousse Publishing, 2012.

2 -In the past years, I created performances called Macchina Dei Disegni (Machine of Drawings), and then I also conducted three closed-access seminars, in three different years, at the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia, which focused precisely on the theme of drawing; they were not aimed at students at the academies, I kept ordinary people, passionate people, in attendance.

Pd’A: So for you, drawing is a method of investigation, an instrument of knowledge to probe the different possibilities of existence?

MD: You cannot delegate knowledge to rational principles alone, the cause-effect relationship does not work in all human fields; the main risk is the dulling and anaesthesia of values that we see rampant in our societies. But already in quantum physics these principles are questioned, and so too in many other fields of science where the involvement of our consciousness in the process of perceiving reality is not excluded.

Art resists any systematisation, it is not undifferentiated and this also has a practical value for us. Art speaks to us about our existence by giving many answers but even more by posing questions. His model has little to do with scientific causality, it cannot be measured, it can only be shared; it is an empirical model, admittedly fragile, it is a tool that involves a series of very personal processes that have our consciousness as their beginning and end. Otherwise, we have no choice but to start measuring intuition, analogies between things, feelings, beauty, poetry, music, emotions, etc.

Pd’A: In your work you often create an intense relationship with the space in which you intervene, how does this happen?

MD: I do not believe that any work of art remains indifferent to the space in which it is placed. There are apparently neutral displays, for example the white cube, certain exhibition stands, but this way of displaying is also a kind of ideology: order, rhythm, 1-zero-1 scanning. In the white cube, it is as if we were turning the pages of a book, where works are often arranged by size or chronological patterns or materials: canvases, graphics, photographic documentation, etc. With our current mentality, imagine visiting an exhibition of the Salon Des Artistes Independants at the end of the 19th century, we would really be in trouble! If we think of the great palaces of the past, their halls, monumental architecture, floors, decorations, and furnishings, we will notice that works of art were placed in relation to those rooms. Often the works overlapped in time with successive interventions, contrasts of different eras and tastes were layered on top of each other, nothing could remain isolated from its context. Our continuous obsession to isolate highlights some typical characteristics of our modernity.

This also raises a question about the concept of the autonomy of the work and especially the social role given to the artist: conditioned by the totemic mythology of the author, as a subject with an individualistic attitude and temperament, isolated in the enclosure of his own very personal experiences.

I do not deny the autonomy of the author and the work, I do not deny that one and the other are bound by an irreducible bond, but both are also embedded in a flow of history that determines the outcome. This happens even unbeknownst to the author, precisely because nothing we create is unrelated to a historical process, and that process is deeply nourished by the past, by what has preceded us.

I believe that the same work placed on a white wall or on a frescoed wall becomes different. It is not a question of a frame, it is a question of contamination, of accumulations of history, of a process of incorporation that also brings into play the meaning of what is shown; because the context can give different results and different interferences. I look a lot for these contrasts or symmetries. The work is only apparently a fragment, and if we want to define it in this way we absolutely have to place this fragment within that continuous fluid that is History, a flow – past/future – that can sometimes be interrupted by placing the spectator in a renewed present.

Pd’A: Your answer opens up a new front, which seems to me to be intimately linked to space, that of time. It seems to me that a plurality of times coexist in your work?

MD: In literature, in music, in cinema, we perceive an arrow of time, we slide into these works as we go; there is a beginning, an unfolding and a conclusion. In front of a painting or a sculpture, the question of time presents itself in a different way.

We spectators are asked for a kind of passivity, an attention that is not generated by any ‘motion’ of the viewed object, apparently it is all there in front of us, we do not ask ourselves:

‘What is he going to do now? – What will happen now?’

We usually remain motionless, perhaps even for a few moments, staring at a painting, this passing time is not a ‘chronological time’ like that of clocks, it is a ‘momentary time’, linked to the body and thought, it has a different interval and above all it is not measurable. (1) Since 2002 I have been producing a particular series of works that I invariably call Mirror. Mirrors, due to an optical effect produced by a prismatic lens, produce a sort of splitting and superimposition of the image; this splitting, however, occurs during the movement of the viewer in front of the painting; it is the opposite of the hologram or the Renaissance perspective, where the viewer is programmatically obliged to a precise position in space.

For example, when looking at a mirror three people close to each other see three different images of the same painting, these are certainly small variations, but it is enough to turn this visual mechanism into a true metaphor: everyone, from their own point of view, interprets what they see differently.

The objectivity of interpretation is only our conjecture, a thesis, a hydra with many faces that does not produce prevailing meanings; I myself, who am the author of Mirrors, cannot say which is the most correct way and position to observe them.

This loss of control is also a very interesting stimulus for me: I do not completely dominate the material of my work but am urged by it to experience and discovery.

(1) Certainly in the visual arts matters are much more complicated than that, just think of sculpture or environmental installations etc. Performance has more of an arrow than time: beginning/end.

Pd’A: Colour?

MD: This of colour is a freedom, I decide from time to time, if I don’t need it I don’t use it, if I need it I use it. I also study the colour palettes of many artists I love. Inside colour we breathe, that’s enough for me, we no longer need justifications. I believe that the chromophobic taboo is slowly disappearing, those who have understood it well, the others catch up! Coloured is no longer synonymous with contaminated, as we enter the 21st century we feel freer from this 20th century ideological prejudice. Colour has been considered by its detractors as childish or vulgar: the impure versus the absolute purity of monochrome etc. The same objections have been made to the ornamental though in different ways and to different degrees.

It could be explored further and it would really be an interesting discourse.

To me, however, they seem like really outdated issues that might be worth reading from a historical, sociological perspective, they tell a lot about us.

It would be even more worthwhile to consider them from the perspective of logic, and the philosophy of language, for example Wittgenstein’s fundamental considerations on colour, or Derek Jarman’s book Chroma or David Batchelor’s beautiful booklet entitled Chromophobia.

Pd’A: Maurizio what relationship do you try to establish with those who look at your work?

MD: <<The paintings are made by those who look at them>>. Duchamp’s phrase is so famous that perhaps it has also become a little worn out over time.

The author, the work, the audience, three distinct but inseparable figures.

Watching in the solitude of one’s own studio a work that has just been completed or looking at it together with another person leads to distinct stimuli: the work in a certain sense changes in meaning.

In etymology ‘to show’ is a transitive verb: to show, to submit to view, to point out, but its Latin root derives from monstru(m) which also means prodigy, sign (divine).

I believe that the participation of the spectator is a fundamental element perhaps because vision also involves ‘the prodigy’. The artist is only the first spectator of a still incomplete spectacle.

Take as a counter-example the images of communication, to be effective they must be direct, or perhaps even indirect, but unambiguous. These images must strive to reduce the misleading element inherent in the reproduced image in order to achieve their goal: the sale of a good.

But even more important is the adherence of this process to a conception of reality so dear to our reason that is called the principle of identity: everything is equal to itself (A=A). The same is true in the didactic image, in the design, in the rendering, in the quality of the details lies the effectiveness of the result which is directly proportional to the correct description, to the adhesion of the image to the object described; the end result, however, is an illustration, an artifice, a caption; the more it describes, the more it adheres to the thing in itself, the better it achieves its purpose.

On the opposite front is the ‘open image’, capable of making unknown elements resonate in the observer, of inducing him to produce analogies, a cascade of latencies, of further references where (A=A) but also (A = B = C ~ ∞).

I cherish the concept of the image as an element of Resonance, a resonator that envisages the spectator.

This motion of the image towards the observer and of the observer towards the image makes the relationship between observer and observed object vital, both become the necessary balancers of meaning.

Ideally this motion should never end, it should always remain in the realm of the ‘almost’ always oscillating and suspended, living image: prodigy and solicitation.

Pd’A: Does exercising non-serial repetition of the sign bring you closer to a spiritual dimension?

Maurizio Donzelli: As you write, repetition is not a programmatic serial element in my case.

I approach repetition more as something linked to an obsession: the obsession for an image, for a pattern, for particular shapes or colours. I don’t mind, once I have an interesting result, being further tempted to repeat it, partly because the image gets better each time, but that is part of the job…

How long can this repetition last? Obviously there is no rule, but I realised that I remain a prisoner of these images of mine for an unspecified period of time. With time I have learnt that it is useless to oppose them, they educate me, they make themselves known, they are part of me but above all I feel that they have their own autonomy.

By posing the problem in this way -the gesture- and its repetition allow you the great freedom to work without thinking, that is -‘to see the image happen’ – in front of your eyes as it unfolds. But it is a balance between your will and your passivity, it is an interesting exercise in which the image makes you feel that you are in resonance with the rest of reality.

The best moments are when in the privacy of your studio the process happens easily, naturally, effortlessly, in these cases everything seems to make sense; but unfortunately this is not often the case.

Pd’A: Maurizio listen, I have seen that you have been doing some embroidery work lately, do you make them yourself or have them made? How do you go about this work?

MD: Actually, they are tapestries that I have made in Belgium using the Jacquard loom technique, which is a particular loom that automates the individual threads of the warp; the Jacquard loom is a type of loom that was invented and perfected back in the 19th century.

This evolution in weaving allows me relative control of the design and a lower cost, although unfortunately tapestries are considerably demanding in terms of economics and production. I could talk at length about tapestries, first of all mentioning the fascination of those dusty colours that absorb and reflect light like no other material; then because this technique gives me the opportunity to develop ideas from both my own images and an elaboration of fragments of ancient tapestries.

Despite all the technological steps, the method is still the same: in the past, the artist would prepare the sketch or the basic design and pass it on to the tapestry maker who would transform it into a tapestry in his own manufactory; today it is still the same, with the advent of numerically controlled machines, the whole process is digitised, but this does not detract from the fact that behind every production there is a great deal of craftsmanship and close contact between the artisans and the artist. Ancient tapestry, at least the one I love the most, begins in the Middle Ages and reaches the threshold of the Renaissance, it has first and foremost a strongly ornamental, but also dreamlike and enigmatic character; the narrative structure is almost fairytale-like, the trees, the foliage, the postures of the characters, the setting in general have an anti-realistic and very symbolic style.

From a certain point onwards, medieval tapestry begins to have to compete with innovations in painting. The invention of oil colour and glazes, the realism of perspective, the attention to shadows and pictorial details, put the tapestry world in crisis, because this technique could not surpass painting in quality, especially fresco painting, which was a direct competitor in terms of size. Let me give just one example: however enormous and sumptuous Raphael’s tapestries are, they are less interesting than his preparatory cartoons. The last great author who certainly closes an era is Bartolomeo Suardi known as Bramantino with his Milanese cycle of the Trivulzio tapestries. In this cycle we still see aspects of late medieval representation mixed with Renaissance concepts and inventions, many constituent fragments of my tapestries come from this series of tapestries.

I realise I have been a little long in the answer but this premise is necessary to describe a working approach. From these assumptions and fascinations come my subsequent elaborations, images where mixed fragments become palindromes and sometimes further mirrored. I believe that it is useless or even harmful to try to describe the content of my images, indeed one of the reasons that drive me to put a tapestry into production is precisely when I recognise something interesting but unknown in it, an image that I cannot understand but only feel, an image equally near and far.

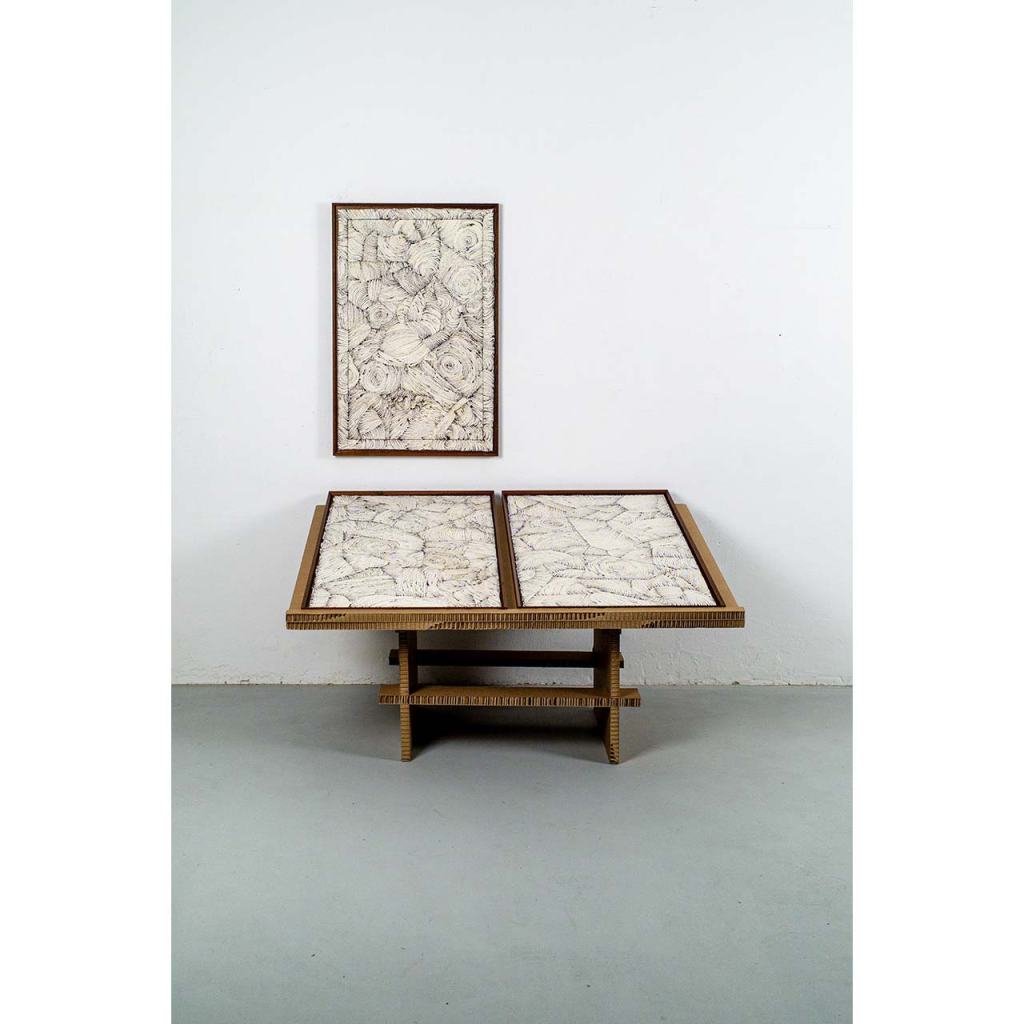

Cartesio Drawings 2022

dittico del quasi 2017 cm130x100x4 cad.

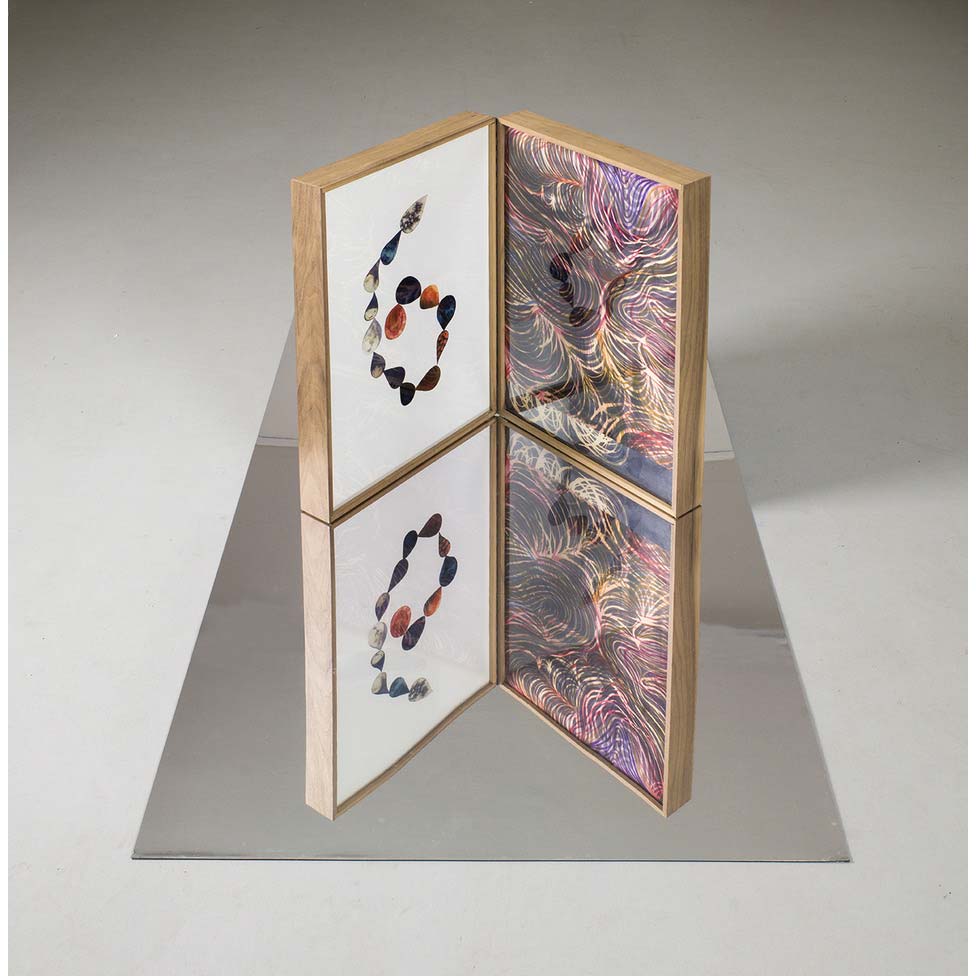

dittico Talisman 2012 cm71x102x8

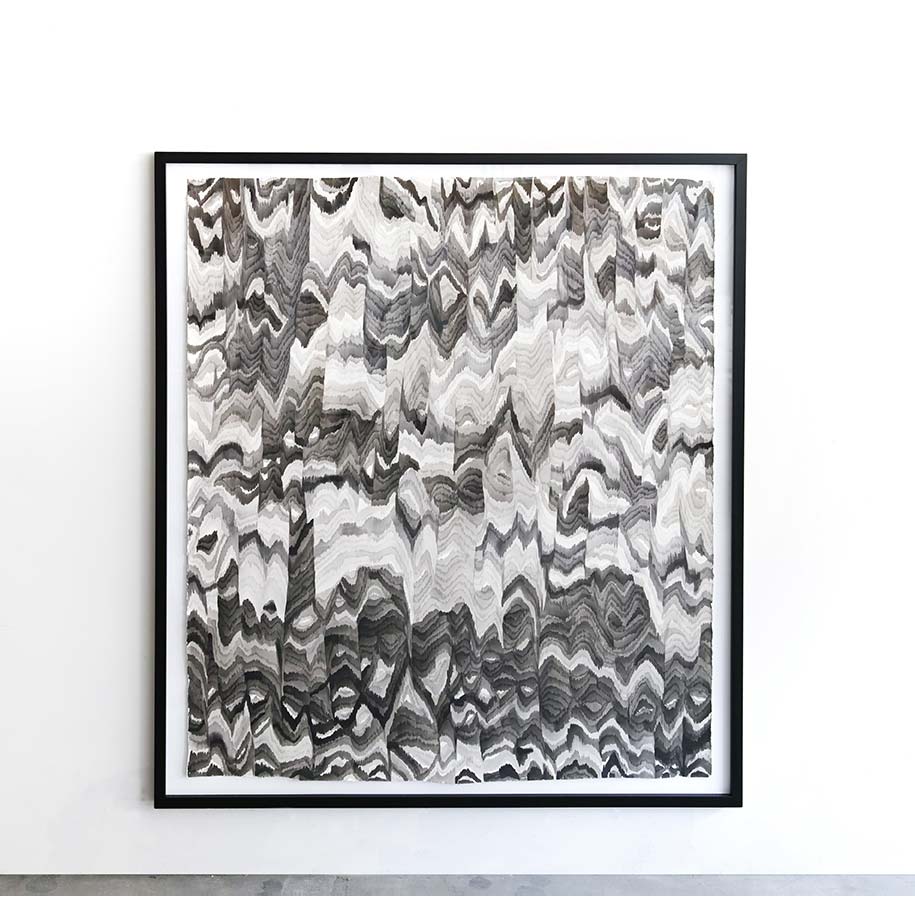

ETCETERA DRAWING 2019 – CM157XH175X4,5

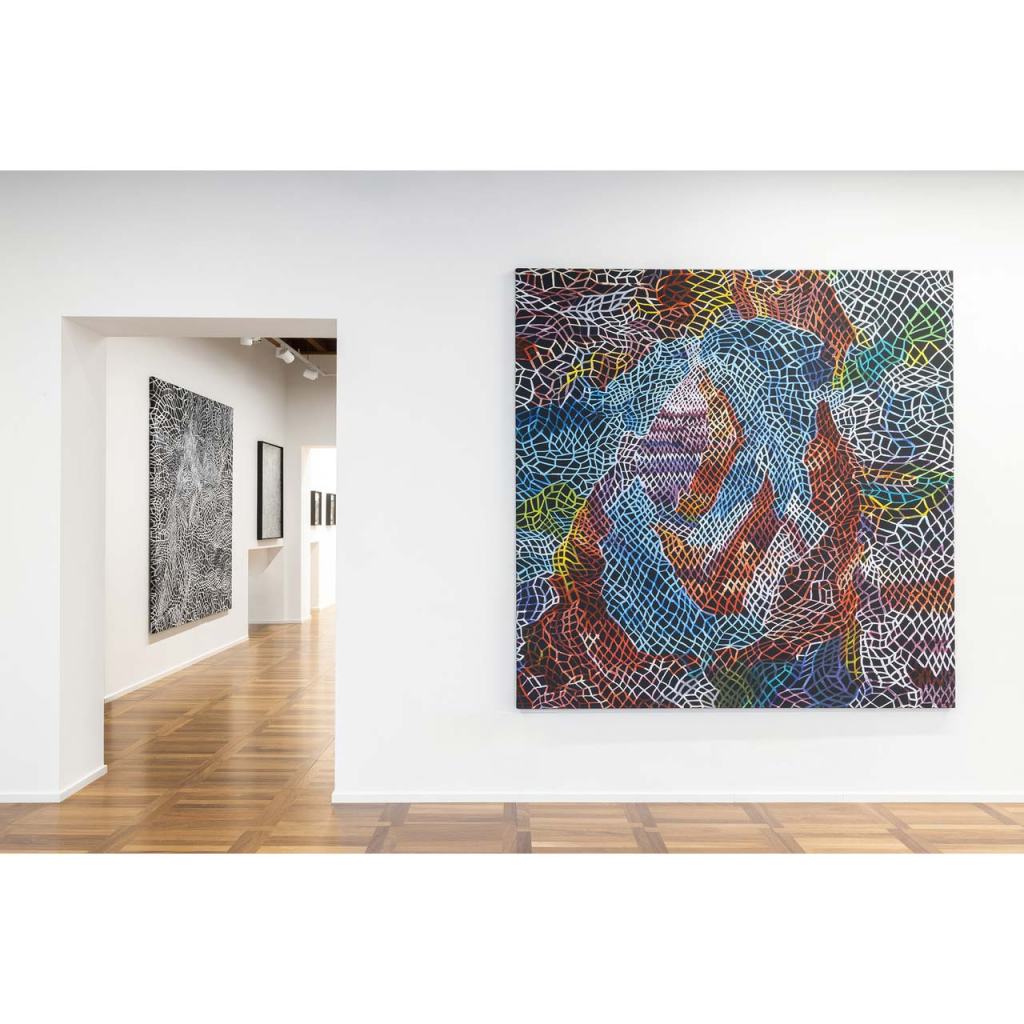

IMMAGINALE galleria Massimo Minini Brescia 2022

NETS 2024

galleria Cortesi Milano copia

MIRROR #2223 CM 53X46X8