(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #jacopozambello #artistinterview

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui iniziano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

JZ: Sono cresciuto in una certa dimensione artistica: mio padre mi insegnava a suonare la chitarra e mia madre mi faceva disegnare. La carriera artistica era una possibilità come le altre. Alle medie ero ugualmente interessato all’arte quanto alle materie scientifiche. La domanda su quale strada intraprendere è stata una questione che ho dovuto risolvere da solo, visto che i miei genitori

supportavano entrambe le scelte. Si può dire, quindi, che sia stato un processo piuttosto organico. Il vero rigurgito interiore lo ho avuto al quinto anno di superiori (Liceo artistico – grafica), quando decisi di andare a fare pittura all’accademia, invece che a una scuola di grafica. La pittura era come una necessità che avevo trascurato fino a quel momento e che adesso richiedeva il suo tempo.

Pd’A: Anche tu, come tanti, hai avuto un primo amore artistico?

JZ: Non so bene come rispondere, ho avuto (e ho tuttora) artisti che ho amato molto. Più avanzo nel mio percorso di ricerca, più riesco a trovare elementi che mi interessano in tutti gli artisti e, allo stesso tempo, quelli che mi erano idoli diventano più umani ai miei occhi. Ho ovviamente delle preferenze personali. Posso dire che, nel mio primo anno di accademia, ho avuto modo di vedere, nell’arco di pochi mesi, la retrospettiva di Luc Tuymans a Palazzo Grassi, un ritratto di Victor Man e uno di Michael Borremans a Ca’ D’Oro. Iniziare confrontandomi con tre giganti della pittura contemporanea lascia il segno.

Pd’A: Puoi descrivere il tuo processo di lavoro?

JZ: Il mio lavoro si divide in cicli tematici, partendo da una macro ricerca sulla percezione della realtà, che via via si suddivide in temi a seconda del periodo.

Metodologicamente, il mio lavoro si sviluppa attraverso una costante ricerca di immagini. Le fonti variano: fotografia amatoriale, materiale d’archivio o la produzione ex novo di reperti fotografici per una particolare serie di lavori. Il materiale fotografico di partenza viene successivamente rielaborato nel disegno, andando a modificarne gli elementi per costruire quella che è l’ossatura dell’immagine finale. Nella fase pittorica, il lavoro subisce ulteriori modifiche, lasciando l’immagine aperta ai suggerimenti della pittura stessa. Più che una bozza, il lavoro di progettazione del dipinto serve a creare una “Moodboard” per descrivere quello che sarà l’opera compiuta, che rappresenta un unicum maggiore della somma delle sue singole parti.

Il dipinto finito può essere un assemblaggio di anche 10 fotografie, unite a modifiche ulteriori tramite il disegno e zone create ex novo dalla pittura (ad esempio, gli sfondi).

Pd’A: Parti da delle fotografie o dipingi dal vero?

JZ: Parto dalle fotografie, mie o d’archivio, fortemente rielaborate da pittura e disegno. Spesso assemblo anche più fotografie insieme e invento intere parti. La mia pittura risulta quindi una cosa altra rispetto al documento fotografico, che uso come uno strumento di pragmaticità. Bacon diceva che la fotografia è più comoda di avere un modello in studio.

Pd’A: Nei tuoi dipinti il soggetto principale è il corpo umano spesso colto mentre si esibisce in vari modi (nudo, azioni sportive…) perché ti interessa tanto ?

JZ: Il corpo non è il mio punto di interesse, ma il soggetto su cui convergono i miei interessi. Posso trovare certe rappresentazioni del corpo incredibilmente noiose e, viceversa, amare profondamente i paesaggi. Trovo nel soggetto umano, figurativo, il vocabolario necessario alla mia ricerca. Se quest’ultima dovesse cambiare direzione, cambierebbero anche i miei soggetti. Personalmente non penso accadrà, almeno nel breve periodo, perché, per quanto sia vero quello che ho appena detto, sento una certa tensione interna verso questi soggetti che va assecondata per permettermi di lavorare con agilità. Dipingiamo ciò che possiamo, a prescindere dalla nostra volontà.

Pd’A: Che importanza ha per te l’idea di racconto?

JZ: Questa è una domanda che mi sono posto molto durante l’ultimo anno. Per me, il racconto è necessario all’interno del mio lavoro, altrimenti si cadrebbe nell’estetismo. Tuttavia, per me è importante porre ciò che racconto in uno stato di sospensione. L’immagine dei miei dipinti cerca di porre una domanda allo spettatore, non vuole né affermare una verità né tanto meno raccontarla. Nella mia visione, la pittura è uno strumento di narrazione passivo, che lavora sul non-detto.

Pd’A: Il disegno ha una qualche importanza in quello che fai?

JZ: Il disegno è la base fondamentale di tutto il mio lavoro. Lavorare su carta mi dà quella scioltezza di pensiero, senza l’ansia da prestazione che può dare la tela, permettendomi di sperimentare e indagare i soggetti che mi interessano. A livello pratico, si vede subito se nel lavoro di qualcuno c’è stata una fase di disegno prima. Lo sketchbook è un quaderno degli appunti: ogni intuizione può tornare utile, anche a mesi di distanza. Probabilmente è la fase del mio lavoro più personale, dove emergono i miei interessi più profondi.

Pd’A: Che ruolo ha la luce nel tuo lavoro?

JZ: Le tematiche della percezione, che fanno da filo rosso al mio lavoro, portano alla presa di coscienza dell’impossibilità di una comprensione univoca della realtà.

Questa frattura nella nostra percezione, e il senso di horror vacui che ne scaturisce, vuole evidenziare la paradossale esistenza di un filo conduttore tra le varie e molteplici esperienze umane.

La luce, in questo contesto, è uno strumento prezioso. Uso luci forti, ombre, il bianco, la plasticità mediterranea o la foschia tipica delle mie zone (sono originario di Rovigo). Tutti questi elementi servono a calare la scena in differenti declinazioni della realtà tramite la luce.

Pd’A: Ti interessa la dimensione pittorica?

JZ: Nel mio lavoro, la dimensione pittorica e tecnica sono molto importanti. Cerco sempre di non perdermi dietro i tecnicismi della pittura, ma sono in una costante ricerca di materiali e metodi nuovi per fare le cose. All’interno della tela, la dimensione pittorica diventa tutto. La mia pittura si basa molto sulla massa: quantità generose di colore e stratificazioni. La tela è un oggetto che va approcciato con energia, non passivamente, focalizzandosi solo su una resa superficiale dell’immagine. Grazie a questo metodo, trovo spesso nuovi spunti suggeriti dalla pittura stessa.

Pd’A: Che importanza hanno le categorie di tempo e spazio per te?

JZ: La natura della pittura è quella di creare immagini sospese. Se la fotografia cattura l’istante, la pittura lavora su una dimensione temporale dilatata. Nell’istante del dipinto è insito anche il prima e il dopo: non c’è una reale presenza temporale quanto più un’idea. Nel mio lavoro ricerco la dimensione atemporale della pittura.

Lo spazio, nel mio lavoro, è parte dell’opera tanto quanto lo sono le figure. Non c’è una dimensione gerarchica tra lo sfondo e il soggetto: tutto risulta parte di un unicum che è il dipinto. Non si può ragionare in modo scollegato. Spesso sono gli sfondi gli elementi dove interviene maggiormente la pittura libera da reference fotografiche.

Queste due categorie, tempo e spazio, sono le fondamenta su cui poggiano i miei soggetti.

Pd’A: Quando devi fare una mostra ti interessa l’idea di messa in scena del lavoro?

JZ: La considero fondamentale. La mia azione nei confronti dell’allestimento è sempre attiva e in dialogo con lo spazio. Non mi risulta possibile concepire una mostra che prescinda dalla sede espositiva. Accettata l’impossibilità di proteggere il dipinto dalle interferenze visive dello spazio, l’unica azione possibile è appropriarsi dello spazio come strumento narrativo. Concepisco la stanza come un unico lavoro e non come un contenitore, probabilmente con un ragionamento più proprio della scultura/installazione che della pittura. Normalmente lavoro inserendo stampe fotografiche di miei scatti o collage, tele girate, prato sintetico e posizionando le tele in maniera organica, fuori dalla normale linea orizzontale a 160 cm dal centro della tela.

Pd’A: Che importanza ha la relazione che si viene a creare fra i vari lavori che decidi di esporre insieme?

JZ: Come dicevo prima, il mio focus è sulla stanza, non sul singolo lavoro. Se devo sacrificare la giusta visibilità di un lavoro (ad esempio mettendolo molto in alto) per il funzionamento della stanza, lo faccio senza ripensamenti: se non funziona la stanza, non funzionano nemmeno i

dipinti. Quindi la relazione tra i lavori risulta per me importantissima. Spesso porto un unico ciclo in mostra per ottenere la soluzione di continuità più naturale possibile. Come nella pittura, anche nelle mostre vale il principio di parità tra cosa si dice e come lo si dice.

Pd’A: Quando dipingi lavori ad un quadro alla volta o ne lavori più di uno simultaneamente?

JZ: Più di uno simultaneamente. Comincio facendo molti disegni, da questi seleziono i piû interessanti e inizio a lavorare 3-4 tele contemporaneamente. Faccio così sia per ragioni pratiche, per ragioni di tempo, che poter “aprire” il ciclo di lavori e portare avanti più di un ragionamento contemporaneamente.

Pd’A: Che idea hai della bellezza?

JZ: Domanda complessa, la bellezza è una qualità estetica, non esclusivamente visiva, che riguarda la pittura solo in una certa misura. Non cerco il bello ma ciò che è interessante. L’estetismo è una zona dell’immagine di cui cerco di evitare la frequentazione. Probabilmente fraintendiamo, me compreso, il concetto di “bello” con la gradevolezza percettiva. Una definizione, assolutamente personale ed arbitraria, di bello è: la bellezza è ciò che ci suscita una tensione, un interesse, viscerale.

Pd’A: Qual è la tua posizione rispetto al tuo lavoro?

JZ: Penso che il mio lavoro attualmente sia in una fase di crescita costante. Tutto quello che faccio è costantemente da me messo in discussione. La ricerca non si ferma mai e ogni ciclo porta semi nuovi per la produzione di quello successivo. Non tutti i cicli sono di pari qualità, ma sono abbastanza sicuro che la curva sia positiva.

La mia posizione è l’unica possibile per un artista nei confronti del proprio lavoro e si riassume in: è lavoro. Non possiamo che continuare a lavorare, a cercare, a produrre e a mettere in discussione. Non è una partita a breve termine ma si gioca nel lungo periodo. Questo è il bello del nostro mestiere, non si ferma dopo un bel quadro, o magari uno brutto, ma va avanti. L’unico lavoro che ci interessa davvero è quello che faremo domani.

Jacopo Zambello (Rovigo, 1999), frequenta attualmente il biennio di Pittura all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia. Nel 2022 vince la sezione Pittura della XIV edizione del Premio Nocivelli. Nel 2023 vince il Martini International Award al Premio Artivisive San Fedele e viene inserito nel libro “222 Artisti Su Cui Investire” edito Exibart. Èatelierista presso l’Istituzione Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa a Venezia nell’anno 2023-24. Nel 2025 è tra i vincitori dell’ottava edizione di We Art Open. Partecipa a numerose mostre, tra cui: (2025) New Art Frontiers, Altro Mondo Creative Space, Makai City, Filippine; (2024) Campo Magnetico, Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Palazzetto Tito, Venezia; La prima volta, Casa Testori, Novate Milanese (MI); Chi sono io – Indagini sul corpo, Galleria San Fedele Milano; Uscita Pistoia #1, Spazio A, Pistoia; (2023) Antares, Magazzini del Sale, Venezia; (2022) Le Stanze del Contemporaneo, Palazzo Martinengo, Brescia.

English text

Intervista a Jacopo Zambello

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #jacopozambello #artistinterview

Parola d’Artista: For most artists, childhood is the golden age when the first symptoms of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Jacopo Zambello: I grew up in a certain artistic dimension: my father taught me to play the guitar and my mother made me draw. An artistic career was a possibility like any other. In middle school I was equally interested in art as in science subjects. The question of which path to take was a question I had to resolve on my own, since my parents

supported both choices. You could say, therefore, that it was a rather organic process. The real inner turmoil came in my fifth year of high school (Liceo artistico – graphic design), when I decided to go to an academy instead of a graphic design school to do painting. Painting was like a necessity that I had neglected up to that point and that now took its time.

Pd’A: Did you, like many, have a first artistic love?

JZ: I don’t really know how to answer that, I have had (and still have) artists that I loved very much. The more I progress in my research, the more I can find elements that interest me in all artists and, at the same time, those who were idols to me become more human in my eyes. I obviously have personal preferences. I can say that, in my first year at the academy, I was able to see the Luc Tuymans retrospective at Palazzo Grassi, a portrait by Victor Man and one by Michael Borremans at Ca’ D’Oro in the space of a few months. To start by confronting three giants of contemporary painting leaves its mark.

Pd’A: Can you describe your working process?

JZ: My work is divided into thematic cycles, starting with a macro research on the perception of reality, which is gradually subdivided into themes according to the period.

Methodologically, my work is developed through a constant search for images. The sources vary: amateur photography, archive material or the ex-ante production of photographic findings for a particular series of works. The photographic source material is subsequently reworked in the drawing, modifying its elements to construct what is the framework of the final image. In the painting phase, the work undergoes further modifications, leaving the image open to the suggestions of the painting itself. Rather than a draft, the design work of the painting serves to create a ‘moodboard’ to describe what the finished work will be, representing a unicum greater than the sum of its individual parts.

The finished painting may be an assemblage of up to 10 photographs, combined with further modifications through drawing and areas created from scratch by the painting (e.g. backgrounds).

Pd’A: Do you start from photographs or do you paint from life?

JZ: I start from photographs, either my own or from archives, strongly reworked by painting and drawing. I often also assemble several photographs together and invent entire parts. My painting is therefore something other than the photographic document, which I use as a pragmatic tool. Bacon said that photography is more comfortable than having a model in the studio.

Pd’A: In your paintings, the main subject is the human body, often captured while exhibiting itself in various ways (nude, sporting actions…) Why are you so interested?

JZ: The body is not my point of interest, but the subject on which my interests converge. I can find certain representations of the body incredibly boring and, conversely, deeply love landscapes. I find in the human, figurative subject the necessary vocabulary for my research. If the latter were to change direction, my subjects would also change. Personally, I don’t think this will happen, at least in the short term, because as true as what I have just said is, I feel a certain internal tension towards these subjects that needs to be indulged in order to allow me to work with agility. We paint what we can, regardless of our will.

Pd’A: What importance does the idea of storytelling have for you?

JZ:This is a question I have asked myself a lot over the past year. For me, storytelling is necessary within my work, otherwise one would fall into aestheticism. However, it is important for me to place what I narrate in a state of suspension. The image of my paintings tries to pose a question to the viewer, it does not want to state a truth or even tell it. In my vision, painting is a passive narrative tool, working on the unspoken.

Pd’A: Does drawing have any importance in what you do?

JZ: Drawing is the fundamental basis of all my work. Working on paper gives me that fluency of thought, without the performance anxiety that canvas can give, allowing me to experiment and investigate the subjects that interest me. On a practical level, you can immediately see if there has been a drawing phase in someone’s work beforehand. The sketchbook is a notebook: every insight can come in handy, even months later. It is probably the most personal phase of my work, where my deepest interests emerge.

Pd’A: What role does light play in your work?

JZ: The themes of perception, which are the red thread running through my work, lead to an awareness of the impossibility of an unambiguous understanding of reality. This fracture in our perception, and the sense of horror vacui that results from it, is meant to highlight the paradoxical existence of a common thread between the various and multiple human experiences. Light, in this context, is a valuable tool. I use strong light, shadows, white, Mediterranean plasticity or the mist typical of my area (I am originally from Rovigo). All these elements serve to cast the scene in different declinations of reality through light.

Pd’A: Are you interested in the pictorial dimension?

JZ: In my work, the pictorial and technical dimensions are very important. I always try not to get lost behind the technicalities of painting, but I am in a constant search for new materials and methods to do things. Within the canvas, the pictorial dimension becomes everything. My painting relies heavily on mass: generous amounts of colour and layering. The canvas is an object that must be approached with energy, not passively, focusing only on a superficial rendering of the image. Thanks to this method, I often find new ideas suggested by the painting itself.

Pd’A: What importance do the categories of time and space have for you?

JZ: The nature of painting is to create suspended images. If photography captures the instant, painting works on a dilated temporal dimension. Inherent in the moment of the painting is also the before and after: there is no real temporal presence so much as an idea. In my work, I search for the timeless dimension of painting.

Space, in my work, is as much a part of the work as the figures are. There is no hierarchical dimension between the background and the subject: everything is part of a unicum that is the painting. You cannot think in a disconnected way. It is often the backgrounds that are the elements where painting free of photographic references intervenes the most. These two categories, time and space, are the foundations on which my subjects rest.

Pd’A: When you have an exhibition, are you interested in the idea of staging the work?

JZ: I consider it fundamental. My action towards staging is always active and in dialogue with the space. I cannot conceive of an exhibition that is independent of the exhibition venue. Having accepted the impossibility of protecting the painting from the visual interference of the space, the only possible action is to appropriate the space as a narrative tool. I conceive of the room as a single work and not as a container, probably with a reasoning more proper to sculpture/installation than to painting. I normally work by inserting photographic prints of my own shots or collages, turned canvases, synthetic lawns and positioning the canvases organically, outside the normal horizontal line 160 cm from the centre of the canvas.

Pd’A: How important is the relationship that is created between the various works that you decide to exhibit together?

JZ: As I said before, my focus is on the room, not on the individual work. If I have to sacrifice the right visibility of a work (e.g. by placing it very high up) for the functioning of the room, I do so without second thoughts: if the room doesn’t work, neither do the

paintings will not work either. So the relationship between the works is very important to me. I often bring a single cycle into the exhibition to achieve the most natural solution of continuity possible. As in painting, the principle of parity between what you say and how you say it applies in exhibitions.

Pd’A: When you paint, do you work on one painting at a time or do you work on more than one simultaneously?

JZ: More than one simultaneously. I start by making many drawings, from these I select the most interesting ones and start working on 3-4 canvases simultaneously. I do this both for practical reasons, for reasons of time, and to be able to ‘open up’ the cycle of work and carry out more than one simultaneously.

Pd’A: What is your idea of beauty?

JZ: A complex question, beauty is an aesthetic quality, not exclusively visual, which concerns painting only to a certain extent. I do not seek beauty but what is interesting. Aesthetics is an area of the image that I try to avoid. We probably misunderstand, myself included, the concept of ‘beautiful’ with perceptive pleasantness. An absolutely personal and arbitrary definition of beauty is: beauty is that which arouses a tension in us, an interest, visceral.

Pd’A: Where do you stand with regard to your work?

JZ: I think my work is currently in a constant growth phase. Everything I do is constantly being challenged by me. The research never stops and each cycle brings new seeds for the production of the next one. Not all cycles are of equal quality, but I am pretty sure that the curve is positive.

My position is the only possible position for an artist towards his own work and it can be summed up as: it is work. We can only continue to work, to search, to produce and to question. It is not a short-term game but is played over the long term. That’s the beauty of our job, it doesn’t stop after a good picture, or maybe an ugly one, but it goes on. The only work we are really interested in is what we will do tomorrow.

Jacopo Zambello (Rovigo, 1999) is currently attending the two-year painting course at the Accademia of Fine Arts in Venice. In 2022 he won the Painting section of the 14th edition of the Premio Nocivelli Prize. In 2023 he won the Martini International Award at the San Fedele Artivisive Prize and was included in the book ‘222 Artists to Invest in’ published by Exibart. He isatelierist at the Istituzione Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa in Venice in the year 2023-24. In 2025 he is among the winners of the eighth edition of We Art Open. He participated in numerous exhibitions, including: (2025) New Art Frontiers, Altro Mondo Creative Space, Makai City, Philippines; (2024) Magnetic Field, Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Palazzetto Tito, Venice; La first time, Casa Testori, Novate Milanese (MI); Chi sono io – Indagini sul corpo, Galleria San Fedele Milan; Uscita Pistoia #1, Spazio A, Pistoia; (2023) Antares, Magazzini del Sale, Venice; (2022) Le Stanze del Contemporaneo, Palazzo Martinengo, Brescia.

PH Giovanna Trestini

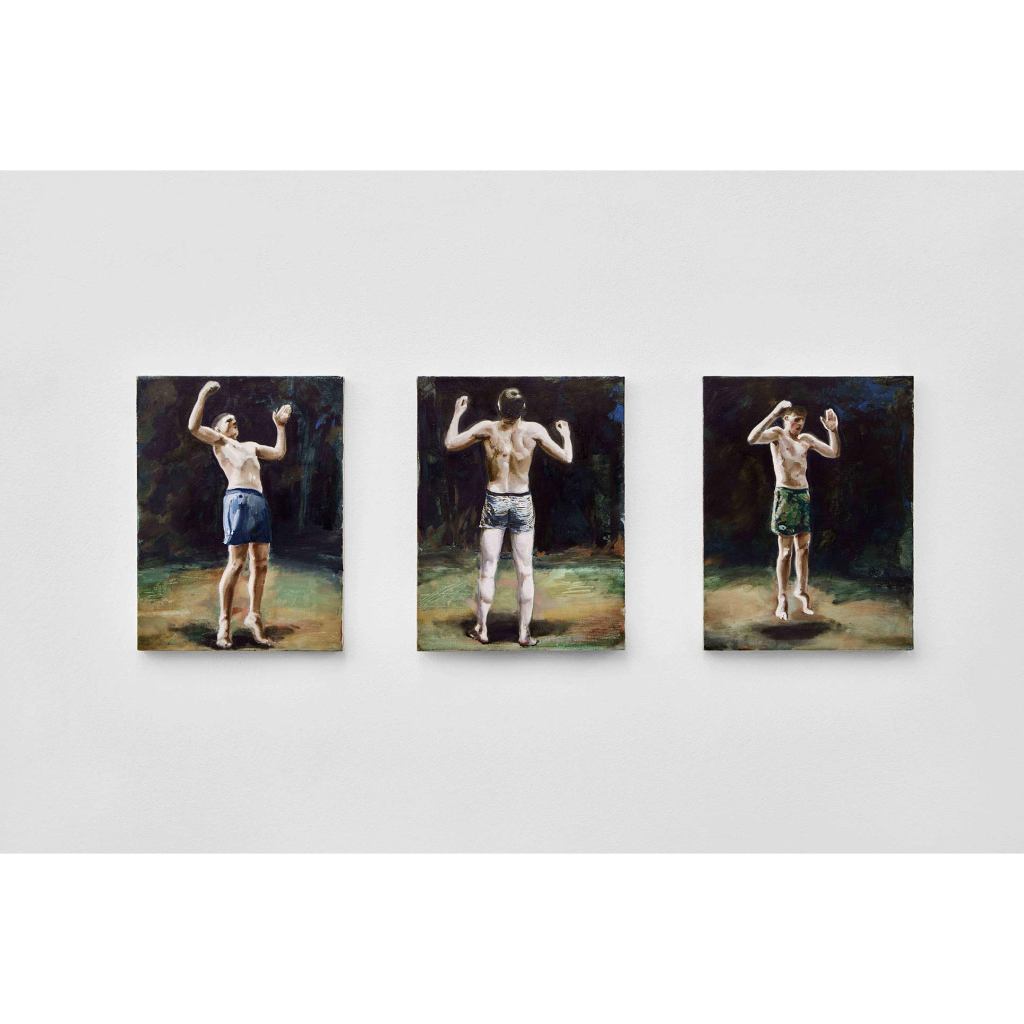

Questione di poco, 30×40 cm, olio e acrilico su tela, 2024

Giacomo Bianco

Gilgamesh ed Enkidu, 180×140 cm, acrilico e olio su tela, 2024

Spasmo Ipnico (serie), 40×30 cm, olio su tela, 2024

Morbido Pungente, 116×170 cm, olio e acrilico su tela, 2024