(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistacuratrice #artcuretorinterview #ilariamonti

Parola d’Artista: Come nasce il tuo interesse per l’arte e in particolar modo quello per l’arte contemporanea?

Ilaria Monti: Semplicemente come una progressiva sedimentazione di stimoli, letture, esperienze, di sensibilità maturata. Se inizialmente è stata un’abitudine, un “lessico famigliare”, in seguito, ho riconosciuto nell’arte una palestra per lo sguardo, dove potevo affiancare all’esercizio estetico la pratica di altre discipline di mio interesse – la poesia e la letteratura, la filosofia e l’antropologia, in generale forme di complessità con cui interrogare o leggere il quotidiano.

Pd’A: Che studi hai fatto?

IM: Diplomata al Liceo Classico, ho studiato Lettere moderne e contemporanee presso l’Università degli Studi di Macerata, conseguendo poi la Laurea Magistrale in Storia dell’arte all’Università Sapienza di Roma e un Master di I livello in Management delle Risorse Artistiche e Culturali. Oscillando tra immagine e parola, tra l’antico e il contemporaneo, credo che il mio percorso di studi abbia nutrito il mio interesse per il linguaggio non verbale e il segno – una dimensione che in qualche modo orienta le mie preferenze e il mio gusto sulla produzione artistica, e su cui ultimamente rifletto molto, soprattutto durante la scrittura di un testo che accompagna una mostra, o di un mio personale testo poetico.

Pd’A: Ci sono stati degli incontri importanti durante gli anni della tua formazione che hanno in qualche modo avuto un influsso sullo sviluppo del tuo lavoro?

IM: Gli anni della formazione non finiranno mai, probabilmente: ogni nuova collaborazione, ogni conversazione in qualche modo arricchisce il già fatto, contribuisce a riformulare e a mettere costantemente in discussione proprio lavoro. Certamente ci sono stati incontri importanti, confronti con artistə, curatorə, galleristə che ho conosciuto o con cui ho collaborato direttamente, e che con la loro visione e tenacia spesso hanno rappresentato una fonte d’ispirazione per continuare a portare avanti i miei progetti e a scommettere sui nuovi. Menzionerei forse due incontri tra tutti: il primo è l’artista Matteo Manfrini, di cui ho curato una delle mie prime mostre. Ci siamo conosciuti in Toscana, mentre lui terminava una collaborazione con Bertozzi e Casoni. A quasi cinque anni e molti chilometri di distanza, io e Matteo ancora ci osserviamo, ci confrontiamo sulle rispettive pratiche, condividiamo una nostra biblioteca e una geografia che è il nostro terreno comune. Con Matteo, infine, c’è stata occasione di conversare con il curatore e critico Pier Luigi Tazzi. Ogni sua parola, la sua interminabile curiosità per gli altri e gli altrove, sono state per noi stimolo per lunghe discussioni sul sistema dell’arte. Il secondo, Massimo Allevato, fondatore del project space DISPLAY (Parma) insieme a perfettipietro. Collaborando con Massimo, che ama il lavoro in solitudine quanto me, ho imparato cosa significa condividere una visione e farla maturare, trovando nel team che abbiamo lentamente costruito come uno spazio in cui si incontrano intuizione, libertà espressiva, e, di tanto in tanto, utopia e sana anarchia.

Pd’A: Come intendi il tuo lavoro?

IM: Come un esercizio musicale quando si tratta di coordinare e comporre testi e mostre; come un cantiere edilizio quando si tratta di ri-costruire e de-codificare percorsi e spazi espositivi. Potrei andare avanti a lungo con le similitudini, che si tratti di raccontare la ricerca anche iconografica che spesso accompagna la curatela o l’insegnamento della storia dell’arte, attività che svolgo nei licei parallelamente da diversi anni. Potrei persino banalmente intenderla come una battuta di caccia, quando invece il lavoro impone il fundraising.

Pd’A: Oggi ha ancora senso l’idea di critico militante?

IM: Mi sembra che la critica militante abbia perso oggi parte della sua incisività e centralità, sostituita dalla cronaca e a recensioni neutrali o apolegetiche, e che in generale il dibattito critico sia sommesso, praticato in sordina, nei salotti o in piccoli spazi dell’editoria d’arte. Forse si è persa la cultura della critica? Forse la critica stessa ha snaturato la sua funzione prima di formulare giudizio? È scettica verso l’adozione o la proposta di nuovi sistemi di riferimento? Forse siamo noi oggi dispersivi e riluttanti nei confronti dei sistemi stessi? Viva Artforum, Flash Art, e-flux e chi più ne ha chi ne metta, ma nell’attesa di godermi un bel botta e risposta tra professionisti dell’arte sulla prima pagina di un quotidiano nazionale, io continuo a farmi domande. Ad esempio, mi chiedo quale sintesi del nostro tempo verrà consegnata agli studiosi del futuro. Nell’affollato panorama dell’arte, quali mostre, quali artistə, quali riflessioni sopravviveranno? Credo che la critica militante e indipendente possa ancora essere uno strumento capace di individuare e tracciare, oggi e per il domani, le principali ricerche in campo artistico. Raccogliendo e aggiornando l’eredità teorica del secondo Novecento, ma navigando tra nuovi media e linguaggi tradizionali, chi se non il critico militante può offrire chiavi di lettura che tengano conto dell’evoluzione, ad esempio, dei gender studies, del pensiero ecologico o delle tecniche artistiche al tempo dell’Intelligenza Artificiale, insomma chi contestualizza – e non necessariamente interpreta o spiega – l’arte alla luce di tutti quegli elementi e paradigmi che legano indissolubilmente la produzione estetica all’immaginario del presente? Continuo a rispondere a questa tua domanda con altre domande.

Pd’A: Che differenza esiste secondo te fra il curatore il critico e lo storico dell’arte?

IM: È un gioco di inversione e sovrapposizione ruoli e maquillage. Spesso accade che siano gli artisti e le artiste stesse a curare le mostre, e anche con successo. Nel distinguere i tre ruoli, forse è significativa la relazione che questi instaurano da una parte con artisti e artiste coinvolte, dall’ altro con il pubblico nell’evento “mostra” o “testo critico” o “pubblicazione”. Dovessi formulare una distinzione, direi che il curatore propone una narrazione (politica, storico-geografica, iconografica, tematica) attraverso una personale ricerca e selezione di opere; media tra opera e pubblico anche attraverso l’allestimento. Su questo punto mi torna in mente un passaggio di Harald Szeemann in una sua intervista. Diceva, negli anni ’70, che le sfida delle mostre del futuro sarebbe stata proprio nel rapporto con il pubblico, e che una tra le vie curatoriali che stava prendendo piede era quella di introdurre nelle mostre concetti estranei all’arte, lasciando alle opere il compito di illustrarli. Curioso quanto non molto sia cambiato. Venendo al critico, come un cartografo dovrebbe tracciare mappe del presente – e, soprattutto, decolonizzare il presente, instaurare dialoghi inediti, sollevare dubbi, creare riverberi ed eco perché le opere, eventualmente, continuino a parlare da sé. Lo storico dell’arte custodisce la trasmissione e la lettura diacronica delle opere, oggi proponendo narrazioni aperte e non lineari dello sviluppo dei linguaggi e delle tecniche artistiche. Ma come dicevo, salvo i casi in cui il curatore o la curatrice abbiano un profilo altro rispetto agli studi sulla cultura visiva, sono ruoli che oggi tendono a sfumare l’uno nell’altro, o a convergere in una figura unica.

Pd’A: Nella babele dei linguaggi visivi della contemporaneità c’è qualcosa che prediligi e che cosa ti attrae di questi linguaggi?

IM: Sono abbastanza onnivora, e non è detto che sia un bene. Un’opera mi colpisce intuitivamente o poeticamente, può disturbarmi, sedurmi, o risuonarmi dentro perché tocca corde particolari, o perché mi stimola e incuriosisce su vari aspetti – simbolici, contenutistici o tecnici, che poi approfondisco. Si tratta della possibilità di instaurare un dialogo con l’opera, riconoscere sul retro o in superficie la traccia di un percorso possibile, qualsiasi esso sia.

Pd’A: In che modo ti avvicini al lavoro di un’artista?

IM: Ultimamente preferisco avvicinarmi di soppiatto, lentamente. Prima di cercare il contatto con l’artista sbircio il suo lavoro da lontano, mi documento, leggo, e osservo, archivio il loro portfolio per consultarlo più volte. Quando possibile, mi piace conoscere prima il lavoro, poi la persona. Una volta instaurata la mia personale relazione con l’opera, mi piace approfondire e conversare con gli artisti e le artiste, frequentare i loro studi di persona o, come spesso accade durante la scoperta di un artista internazionale, trasporre lo studio visit online. In ogni caso, cerco di costruire insieme uno spazio di immediatezza e spontaneità per accogliere e apprendere il loro lavoro.

Pd’A: Secondo te il sacro ha ancora una sua importanza nell’arte di oggi?

IM: In generale, soprattutto in certa produzione saggistica sulla cultura visiva contemporanea, si riscontra un revival di termini, simboli e immagini che alludono alla mistica medievale o ad una “spiritualità ecologica”, a forme e spazi di un sacro rivitalizzato e recuperato a tratti come antidoto e dimensione altra rispetto a quella iper-tecnologica. Il sacro è una fantasia, retaggio di un sistema valoriale, di un pensiero magico il cui recupero oggi è anche spesso accompagnato alla critica sociale – penso a Feet First, la rana crocifissa di Martin Kippenberger, alla celeberrima Nona ora di Cattelan, ma gli esempi, anche più recenti, sono innumerevoli. Quanto fascino, e quante proposte espositive all’interno di chiostri, chiese, o luoghi sconsacrati. Direi che il sacro è un simulacro che produce simulacri, un breviario di riti, una sopravvivenza di culti-culture e pratiche simboliche. Non saprei misurare la sua rilevanza, ma mi sembra essere un fenomeno, una metafora complessa e archetipica che ha destato e desta tutt’ora un certo interesse da parte di artistə e curatorə, interesse che forse risponde anche ad un antico bisogno (o malanno) individuale e collettivo di identificazione e riconoscimento reciproco, di sentirsi parte di una comunità di pratiche. Ciò che mi sembra rilevante sottolineare è che nelle comunità, ieri come oggi, il sacro è legittimazione aprioristica e manifestazione di un’autorità spirituale, politica o sociale che agisce su un primordiale bisogno di credere, trascendersi, salvarsi e posizionarsi nello spazio performativo e normativo che il sacro stesso delinea proprio attraverso i riti, le estetiche e i dogmi, le narrazioni veicolate. Forse è proprio questo che l’arte contemporanea evidenzia o contesta, quando emula, si appropria, replica o riformula forme e dinamiche del sacro.

Pd’A: Che ruolo hanno e che effetto producono i social sul sistema dell’arte?

IM: È chiaro ormai che i social funzionino come vetrine o biglietti da visita, moltiplicatori di immagini e diffusori di estetiche. Già una decina di anni fa In After Art David Joselit approfondiva il tema della distribuzione e circolazione delle immagini, di arte e architettura nell’era del global network, e quindi del loro essere ovunque simultaneamente, evidenziando come certi artisti operassero come “motori di ricerca umani”. Sia dal punto di vista della produzione, che dal punto di vista della fruizione, sui social l’arte diventa irrimediabilmente un fatto relazionale a tu per tu, manifestandosi o apparendo in uno spazio universalmente accessibile e in grado di incrementare – o determinare – la popolarità di un’opera o del programma di una galleria o di un qualsiasi spazio espositivo. Io non li demonizzo, non sono altro che strumenti con le proprie regole d’uso e i propri limiti e, come ogni altro dispositivo, possiamo beneficiare del loro utilizzo. Parlo da scroller compulsiva: penso sia capitato a tuttə noi di scoprire un nuovo artista o nuovi spazi non solo scrollando, ma entrando nel labirintico percorso di pagine e nomi che l’algoritmo ci suggerisce di seguire. È vero, viviamo in una compulsione di immagini, e di tanto in tanto è sano ritirarsi dal dominio visivo dei social. Penso comunque che, se usati intelligentemente, questi possano essere mezzi di scoperta e costruzione di personali archivi digitali. Allo stesso tempo, i social sfidano la nostra conoscenza e la nostra esperienza dell’opera, costringendoci, se vogliamo, a chiederci cosa e quale significato lo schermo sta proiettando, se abbiamo davanti un’immagine manipolata o un’appropriazione, quali dettagli ci stiamo perdendo sostituendo l’esperienza fisica di un’opera con il suo doppio pixelato.

Pd’A: Che idea hai della bellezza?

IM: Dipende, credo, dal campo di applicazione del termine. “Bellezza” è una parola problematica, che oggi non ha nulla a che fare con l’idea di piacevolezza estetica. Per me “bello” è un aggettivo che non aggiunge alcuna informazione sulla qualità o le caratteristiche di un oggetto o un paesaggio, un prodotto artistico, un testo, una persona. La categoria del bello è un fantasma che abita solo scomodamente la società contemporanea. Una nuova bellezza viene fondata e rifondata ogni giorno, convive con le storture, le aberrazioni, le catastrofi, cui fa da controcanto. Chiudi gli occhi, ascoltami mentre ti descrivo un’opera che secondo il mio gusto è “bella”. Con ogni probabilità la tua mente produrrebbe un’immagine completamente diversa dalla mia.

English text

Interview to Ilaria Monti

#paroladartista #intervistacuratrice #artcuretorinterview #ilariamonti

Parola d’Artista: How did your interest in art, and particularly in contemporary art, start?

Ilaria Monti: Simply as a progressive sedimentation of stimuli, readings, experiences, of matured sensibility. If at first it was a habit, a ‘familiar lexicon’, later on, I recognised art as a gym for the gaze, where I could combine the aesthetic exercise with the practice of other disciplines of interest to me – poetry and literature, philosophy and anthropology, in general forms of complexity with which to interrogate or read the everyday.

Pd’A: What studies did you do?

IM: After graduating from Classical High School, I studied Modern and Contemporary Literature at the University of Macerata, and later obtained a Master’s Degree in Art History at the Sapienza University of Rome and a Level I Master’s Degree in Management of Artistic and Cultural Resources. Oscillating between image and word, between the ancient and the contemporary, I believe that my course of study has nurtured my interest in non-verbal language and the sign – a dimension that in some ways orients my preferences and taste in artistic production, and on which I have been reflecting a great deal lately, especially when writing a text to accompany an exhibition, or my own personal poetic text.

Pd’A: Were there any important encounters during your formative years that somehow had an influence on the development of your work?

IM: The formative years will probably never end: every new collaboration, every conversation in some way enriches what has already been done, helps to reformulate and constantly question one’s own work. Certainly there have been important encounters, confrontations with artistsə, curatorsə, galleristsə whom I have met or collaborated with directly, and who with their vision and tenacity have often been a source of inspiration to continue pursuing my projects and betting on new ones. I would mention perhaps two encounters out of all: the first is the artist Matteo Manfrini, whose work I curated one of my first exhibitions. We met in Tuscany, while he was finishing a collaboration with Bertozzi and Casoni. Almost five years and many kilometres later, Matteo and I still observe each other, discuss our respective practices, share a library and a geography that is our common ground. With Matteo, we had the opportunity to converse with curator and critic Pier Luigi Tazzi. Every word he said, his endless curiosity for others and elsewhere, was for us a stimulus for long discussions on the art system. The second, Massimo Allevato, founder of the project space DISPLAY (Parma) together with perfettipietro. Collaborating with Massimo, who loves working alone as much as I do, I have learnt what it means to share a vision and let it mature, finding in the team we have slowly built a space where intuition, freedom of expression, and, from time to time, utopia and healthy anarchy meet.

Pd’A: How do you understand your work?

IM: As a musical exercise when it comes to coordinating and composing texts and exhibitions; as a construction site when it comes to rebuilding and de-codifying routes and exhibition spaces. I could go on for a long time with the similarities, whether I am talking about the research, including iconographic research, that often accompanies curating or teaching art history, an activity I have been doing in high schools in parallel for several years. I could even banally think of it as a hunting trip, when the work requires fundraising.

Pd’A: Does the idea of the militant critic still make sense today?

IM: It seems to me that militant criticism has lost some of its incisiveness and centrality today, replaced by news reporting and neutral or apolegetic reviews, and that in general critical debate is subdued, practised in silence, in drawing rooms or small spaces of art publishing. Perhaps the culture of criticism has been lost? Perhaps criticism itself has distorted its function before formulating judgement? Is it sceptical towards adopting or proposing new systems of reference? Perhaps it is we who are today dispersive and reluctant towards the systems themselves? Long live Artforum, Flash Art, e-flux and so on and so forth, but while I wait to enjoy a nice repartee between art professionals on the front page of a national newspaper, I keep asking myself questions. For example, I wonder what synthesis of our time will be delivered to the scholars of the future. In the crowded art scene, which exhibitions, which artistə, which reflections will survive? I believe that militant and independent criticism can still be an instrument capable of identifying and mapping out, today and for tomorrow, the main research in the field of art. Gathering and updating the theoretical legacy of the second half of the 20th century, but navigating between new media and traditional languages, who if not the militant critic can offer keys to interpretation that take into account the evolution of, for example, gender studies, ecological thinking or artistic techniques at the time of Artificial Intelligence, in short, who contextualises – and does not necessarily interpret or explain – art in the light of all those elements and paradigms that indissolubly link aesthetic production to the imaginary of the present? I continue to answer this question of yours with other questions.

Pd’A: What difference do you think there is between the curator the critic and the art historian?

IM: It is a game of role reversal and overlapping. It often happens that it is the artists themselves who curate the exhibitions, and successfully too. In distinguishing the three roles, perhaps the relationship they establish with the artists involved on the one hand, and with the audience in the event ‘exhibition’ or ‘critical text’ or ‘publication’ on the other, is significant. If I had to formulate a distinction, I would say that the curator proposes a narrative (political, historical-geographical, iconographic, thematic) through a personal research and selection of works; he also mediates between work and audience through the set-up. On this point, I am reminded of a passage by Harald Szeemann in one of his interviews. He said, in the 1970s, that the challenge of the exhibitions of the future would be precisely in the relationship with the public, and that one of the curatorial avenues that was gaining ground was that of introducing concepts foreign to art into exhibitions, leaving the works to illustrate them. Curious how not much has changed. Coming to the critic, like a cartographer, he should draw maps of the present – and, above all, decolonise the present, establish unprecedented dialogues, raise doubts, create reverberations and echoes so that the works eventually continue to speak for themselves. The art historian guards the transmission and diachronic reading of works, today proposing open and non-linear narratives of the development of artistic languages and techniques. But as I was saying, except in cases where the curator or curator has a different profile from visual culture studies, these are roles that today tend to blur into one another, or converge into a single figure.

Pd’A: In the babel of contemporary visual languages, is there anything you favour and what attracts you to these languages?

IM: I am quite omnivorous, and that’s not necessarily a good thing. A work strikes me intuitively or poetically, it can disturb me, seduce me, or resonate within me because it touches particular chords, or because it stimulates me and makes me curious about various aspects – symbolic, content or technical, which I then delve into. It is about the possibility of establishing a dialogue with the work, recognising on the back or on the surface the trace of a possible path, whatever it may be.

Pd’A: How do you approach an artist’s work?

IM: Lately I prefer to approach it stealthily, slowly. Before I seek contact with the artist I peek at their work from afar, I document, read, and observe, I archive their portfolio to consult it again and again. Whenever possible, I like to get to know the work first, then the person. Once I have established my personal relationship with the work, I like to explore and converse with the artists, visit their studios in person or, as often happens when discovering an international artist, transpose the studio visit online. In any case, I try to build together a space of immediacy and spontaneity to welcome and learn about their work.

Pd’A: Do you think the sacred still has an importance in art today?

IM: In general, especially in certain non-fiction production on contemporary visual culture, there is a revival of terms, symbols and images that allude to mediaeval mysticism or an ‘ecological spirituality’, to forms and spaces of a revitalised sacredness recovered at times as an antidote and a dimension other than the hyper-technological one. The sacred is a fantasy, the legacy of a system of values, of a magical thought whose recovery today is also often accompanied by social criticism – I am thinking of Feet First, Martin Kippenberger’s crucified frog, Cattelan’s celebrated Ninth Hour, but there are countless examples, including more recent ones. How fascinating, and how many exhibition proposals inside cloisters, churches, or deconsecrated places. I would say that the sacred is a simulacrum producing simulacra, a breviary of rites, a survival of cult-cultures and symbolic practices. I do not know how to measure its relevance, but it seems to me to be a phenomenon, a complex and archetypal metaphor that has aroused and still arouses a certain interest on the part of artistsə and curatorsə, an interest that perhaps also responds to an ancient individual and collective need (or ailment) for mutual identification and recognition, for feeling part of a community of practices. What seems relevant to me to emphasise is that in communities, yesterday as today, the sacred is aprioristic legitimation and manifestation of a spiritual, political or social authority that acts on a primordial need to believe, transcend oneself, save oneself and position oneself in the performative and normative space that the sacred itself delineates precisely through rites, aesthetics and dogmas, and the narratives conveyed. Perhaps it is precisely this that contemporary art highlights or challenges, when it emulates, appropriates, replicates or reformulates forms and dynamics of the sacred.

Pd’A: What role do social media play and what effect do they have on the art system?

IM: It is clear by now that social networks function as showcases or business cards, multipliers of images and disseminators of aesthetics. Already a decade ago, in After Art, David Joselit explored the theme of the distribution and circulation of images, of art and architecture in the era of the global network, and therefore of their being everywhere at once, pointing out how certain artists operated as ‘human search engines’. Both from the point of view of production, and from the point of view of fruition, on social networks, art becomes irretrievably a face-to-face relational fact, manifesting itself or appearing in a universally accessible space and able to increase – or determine – the popularity of a work or programme of a gallery or any exhibition space. I do not demonise them, they are nothing more than tools with their own rules of use and limitations and, like any other device, we can benefit from their use. I speak as a compulsive scroller: I think it has happened to all of us to discover a new artist or new spaces not only by scrolling, but by entering the labyrinthine path of pages and names that the algorithm suggests we follow. True, we live in a compulsion of images, and from time to time it is healthy to withdraw from the visual domain of social media. However, I think that, if used intelligently, they can be means of discovery and construction of personal digital archives. At the same time, social challenges our knowledge and experience of the work, forcing us, if we wish, to ask ourselves what and what meaning the screen is projecting, whether we are looking at a manipulated image or an appropriation, what details we are missing by replacing the physical experience of a work with its pixelated double.

Pd’A: What is your idea of beauty?

IM: It depends, I think, on the scope of the term. ‘Beauty’ is a problematic word, which today has nothing to do with the idea of aesthetic pleasantness. For me, ‘beautiful’ is an adjective that adds no information about the quality or characteristics of an object or landscape, an artistic product, a text, a person. The category of beauty is a ghost that only uncomfortably inhabits contemporary society. A new beauty is founded and refounded every day, it coexists with the distortions, aberrations, catastrophes, to which it acts as a counterpoint. Close your eyes, listen to me describe a work that is ‘beautiful’ to my taste. In all probability your mind would produce a completely different image from mine.

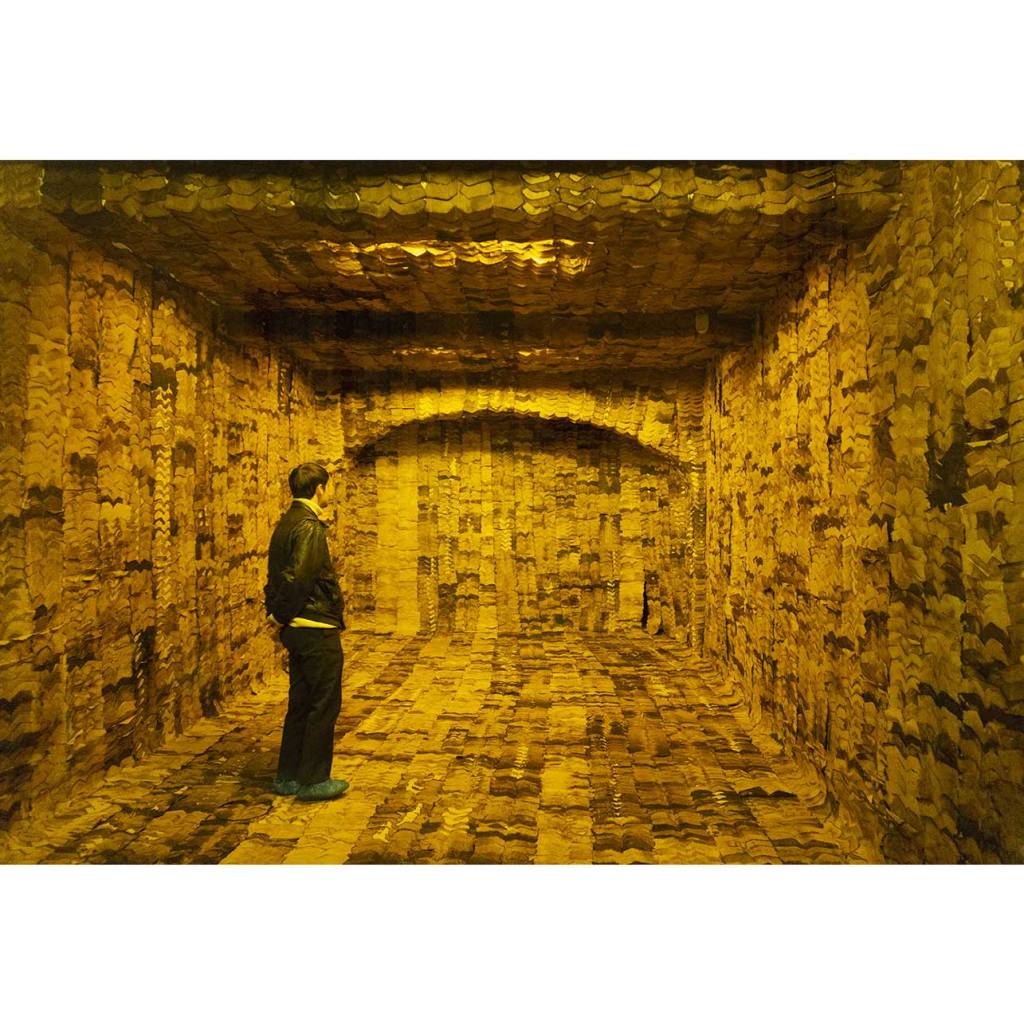

Courtesy of the Artist and DISPLAY

Galleria Fidia, Roma, IT

Courtesy of the Artist and Galleria Fidia

Ph. Giorgio Benni

Courtesy of the Artist

Courtesy of the Artist

Ph. Marco Zanotti

Courtesy of the Artist and DISPLAY

Ph. Alessandra Bonanotte e Pierluigi Bove