(Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistacritica #artcriticsinterview #chiaraguidi

Parola d’Artista: Come nasce il tuo interesse per l’arte e in particolar modo quello per l’arte contemporanea?

Chiara Guidi: Il mio interesse per l’arte contemporanea nasce emotivamente e come oggetto di studio, dalle prime scuole elementari: avevo vinto un concorso di poesia su Topolino e, ho scelto come dono: “I Maestri italiano del Novecento” un volume rilegato di Liliana Bortolon, per la Mondadori, quasi un manuale che io consultavo regolarmente e che mi ha portato direttamente a Giorgio De Chirico come approdo a una idea inusuale di modernità.

Pd’A: Che studi hai fatto?

C.G.: Dopo il liceo classico, ho fatto Lettere a indirizzo artistico (storia dell’arte contemporanea) a Firenze e poi ho proseguito a Milano per una nuova corso di laurea in Storia della Critica d’Arte.

Pd’A: Ci sono stati degli incontri importanti durante gli anni della tua formazione che hanno in qualche modo avuto un influsso sullo sviluppo del tuo lavoro?

C.G.: Si si, sono stato diversi e determinanti e sono stati proprio gli incontri, i veri atti formativi per lo studio, per la professione.

Te ne accenno solo alcuni. Per primo, in ordine di tempo e di importanza: Giuseppe Chiari. Lui mi ha dato le coordinate essenziali sulle scelte da fare subito, già da studentessa: andare a Milano e lasciare Firenze; partire dalla Seconda Avanguardia come genesi della nostra contemporaneità, saper comprendere il senso di una mostra contemporanea (e lui me lo ha mostrato!) o saper scegliere un tavolo a cui doversi sedere in un caffè frequentato da artist, oltre al senso autentico della performance.

Antonio Trotta che mi ha indicato e fatto vivere traiettorie del contemporaneo in luoghi come Buenos Aires, la stessa Milano operativa delle gallerie, e la formazione degli studi eleatici, che parallelamente alla città di Pietrassbta, hanno determinato il senso innovativo della scultura, non solo in lui, ma nella sua generazione: Luciano Fabro, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Athos Ongaro.

Carlos Espartaco: mi ha insegnato che da quando si mangia al mattino la “media luna”, (cornetto) bisogna già pensare filosoficamente e praticamene a come sopravvivere nelle nostre scelte, alle nostre scelte.

Salvatore Ala che, come Hanna Arendt,sosteneva che la vita è fatta per ricominciare, anche se lui lo esprimeva e lo ha espresso, nel suo agire. Gino De Dominicis che invocava la notte e viveva il mistero. Gianfranco Baruchello che è stata l’artista a cui ho fatto la mia prima intervista e mi ha fornito una utile e preziosa bibliografia, evidenziandone l’importanza. Salvo che mi aperto “il suo primo studio” quello torinese con Boetti. E non posso non ricordare Norbert Schwontkowski che nella luce di un tramonto a un party all’Hotel Des Bains, al Lido di Venezia durante una Biennale, mi ha rivelato ogni ombra ferma e pastosa della sua pittura.

Pd’A: Come intendi il tuo lavoro?

C.G.: E’ un lavoro generato dalla disciplina quotidiana, quindi di continuo studio e approfondimento, per non smarrire e/o interrompere, la ricerca e lo studio che è il filo invisibile ma strutturale che lega il vivere all’arte.

Pd’A: Oggi ha ancora senso l’idea di critico militante?

C.G.: Oggi, come Domani, la critica militante continua a essere l’unico modo possibile per fare il critico. Infatti bisogna continuare a testimoniare le scelte, ed è l’unica pratica possibile per comprendere il nostro tempo.

Pd’A: Che differenza esiste secondo te fra il curatore il critico e lo storico dell’arte?

C.G.: Lo storico dell’arte ha materiali da consultare, da conoscere, da approfondire, da studiare, il critico d’arte deve essere prima uno storico, poi diventare conseguentemente colui che crea i materiali.

Pd’A: Nella babele dei linguaggi visivi della contemporaneità c’è qualcosa che prediligi e che cosa ti attrae di questi linguaggi?

C.G.: L’arte è un linguaggio, è il linguaggio è unico. Sono le sue declinazioni della creatività e dei vari media che hanno vibrazioni, e sviluppi continui.

Le uniche “babele” sono i le creatività fini a se stesse, quelle si assommano, si confondono, si perdono, mutano, si contaminano, ma in modo autonomo: e, fanno tutto da sole. E il tempo lo rivela chiaramente.

Ciò che mi attrae è l’opera che persiste nel linguaggio e che è capace di fare “corto circuito”.

Pd’A: In che modo ti avvicini al lavoro di un’artista?

C.G.: La modalità è sempre complessa e ha molteplici strade di contatto e di conoscenza che varia dalla generazione a cui appartiene, ma per tutti vale sempre il principio che dopo essermi “avvicinata” seguo il suo percorso, con un passo nascosto e fedele al suo fianco.

Pd’A: Secondo te il sacro ha ancora una sua importanza nell’arte di oggi?

C.G.: L’arte è sacra.

E, il sacro nell’arte moderna da Ad Reinhardt a Mark Rotko, ha gettato nella prima parte del Novecento il senso sacro della pittura nel suo grado iconoclasta, oltre lo spirituale di Paul Klee e Wassily Kandinsky.

Nella seconda metà del Novecento invece ha conosciuto forte esperienza, in opere inaspettate e non sempre codificate come sacro. Il Cretto di Burri, le Vetrate con pietre dure di Sigmar Polke nella Cattedrale di Zurigo e le vetrate di Gerard Richter nelle 72 tonalità di colore nella Cattedrale di Colonia, le Torri Celesti di Anselm Kiefer all’Hangar Bicocca, e il panoramico The Lightnig Field di Walter De Maria in New Mexico, come l’uso del polline nell’opera si Wolfgang Laib,.La riproposizione spirituale dell’oro nell’arte di Yves Klein, e in quella di James Lee Byers, o nelle Fine di Dio, di Lucio Fontana.. Queste sono solo esempi, senza scendere nell’ iconografia classica come quella della croce, testimoniata nella fotografia di Brigitte Niedermair. La candela bachelardiana di Gerard Richter che è addirittura finita sul vinile anni Ottanta, Daydream Nation: dei Sonic Youth. Seven Magic Mountains” di Ugo Rondinone nel Nevada dove il cromatismo fluo della pietra invoca atti sciamanici. Ripeto che sono solo esempi, di come la specificità di una ricerca linguistica approda al sacro o in vere Cattedrali. Ovviamente senza necessariamente essere commissionata e/o presente nelle costituite “cattedrali”, ma che persistono in quelle dello spirito dell’opera.

Pd’A: Da quando hai iniziato ad occuparti d’arte contemporanea ad oggi come è cambiato il sistema dell’arte?

C.G.: Ogni giorno cambia il sistema, perché la modificazione è ininterrotta sia per il sia per le modalità e sia per i nuovi luoghi dell’arte e per le continue aperture strategiche.

Ma resta sempre tutto affidato al sistema e alle sue centralità (Galleria, Artista, Critico, Collezionista. Oltre alle Istituzioni e alla Editoria specializzata, quando sono presenti.).

Pd’A: Che ruolo hanno e che effetto producono i social sul sistema dell’arte?

C.G.: I social hanno accelerato e ampliato la conoscenza con tempi accelerati. Hanno allargato l’apparente conoscenza, ovvero una estesa e inaspettata divulgazione dell’immagine, che all’inizio del nuovo secolo, con chiamavano globale. Poi per le loro proprietà di divulgazione attraverso l’algoritmo e le loro forme commerciali e l’uso sapiente dei professionisti digitali, che si contrappone a quello dilettantesco, sono divenuti piattaforme utili e contemporaneamente anche bolle che ingannano e confondono. Oltre al dispendio eccessivo del tempo esperito da tutti noi. Ma i social aiutano ad avvicinarsi alla conoscenza e sono un potente strumento che come ogni strumento è utile solo nel loro buon utilizzo.

English text

Interview to Chiara Guidi

#paroladartista #intervistacritica #artcriticsinterview #chiaraguidi

Parola d’Artista: How did your interest in art, and particularly in contemporary art, begin?

Chiara Guidi: My interest in contemporary art was born emotionally and as an object of study, from my first primary schools years: I had won a poetry competition on Mickey Mouse and, I chose as a gift: ‘I Maestri italiano del Novecento’ a bound volume by Liliana Bortolon, for Mondadori, almost a manual that I consulted regularly and that led me directly to Giorgio De Chirico as a landing place for an unusual idea of modernity.

Pd’A: What studies did you do?

C.G.: After classical high school, I did Literature with an artistic specialisation (history of contemporary art) in Florence and then went on to Milan for a new degree in History of Art Criticism.

Pd’A: Were there any important encounters during your formative years that somehow had an influence on the development of your work?

C.G.: Yes, there were several and decisive encounters, the real formative acts for the studio, for the profession.

I’ll mention just a few. First, in order of time and importance: Giuseppe Chiari. He gave me the essential coordinates on the choices I had to make right away, even as a student: to go to Milan and leave Florence; to start from the Second Avant-garde as the genesis of our contemporaneity, to know how to understand the meaning of a contemporary exhibition (and he showed it to me!) or to know how to choose a table at which to sit in a café frequented by artists, as well as the authentic sense of performance.

Antonio Trotta who showed me and made me experience trajectories of the contemporary in places like Buenos Aires, the same operational Milan of galleries, and the formation of the Eleatic studies, which in parallel with the city of Pietrassbta, determined the innovative sense of sculpture, not only in him, but in his generation: Luciano Fabro, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Athos Ongaro.

Carlos Espartaco: he taught me that from the moment one eats the ‘media luna’ (croissant) in the morning, one must already think philosophically and practically about how to survive in our choices.

Salvatore Ala who, like Hanna Arendt, maintained that life is made to begin again, even as he expressed it, and expressed it, in his actions. Gino De Dominicis who invoked the night and lived the mystery. Gianfranco Baruchello who was the artist I interviewed for the first time and provided me with a useful and valuable bibliography, highlighting his importance. Salvo who opened ‘his first studio’ to me in Turin with Boetti. And I cannot fail to mention Norbert Schwontkowski who, in the light of a sunset at a party at the Hotel Des Bains on the Lido in Venice during a Biennale, revealed to me every firm and mellow shadow of his painting.

Pd’A: How do you understand your work?

C.G.: It is a work generated by daily discipline, therefore of continuous study and insight, so as not to lose and/or interrupt, the research and study that is the invisible but structural thread that binds living to art.

Pd’A: Does the idea of the militant critic still make sense today?

C.G.: Today, like tomorrow, militant criticism continues to be the only possible way to be a critic. In fact one must continue to witness choices, and it is the only possible practice to understand our time.

Pd’A: What difference do you think there is between the curator the critic and the art historian?

C.G.: The art historian has materials to consult, to get to know, to study, the art critic must first be a historian, then consequently become the one who creates the materials.

Pd’A: In the babel of contemporary visual languages, is there anything you favour and what attracts you to these languages?

C.G.: Art is a language, and language is unique. It is its declinations of creativity and various media that have vibrations, and continuous developments.

The only ‘Babel’ are the creativities that are an end in themselves, those assimilate, mingle, get lost, mutate, contaminate, but in an autonomous way: and, they do it all by themselves. And time reveals this clearly.

What attracts me is the work that persists in language and is capable of ‘short-circuiting’.

Pd’A: How do you approach the work of an artist?

C.G.: The way is always complex and has multiple ways of contact and knowledge that varies according to the generation to which it belongs, but for everyone the principle always applies that after having ‘approached’ me, I follow its path, with a hidden and faithful step at its side.

Pd’A: In your opinion, does the sacred still have an importance in today’s art?

C.G.: Art is sacred.

And, the sacred in modern art from Ad Reinhardt to Mark Rotko, cast in the first part of the 20th century the sacred sense of painting in its iconoclastic degree, beyond the spiritual of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

In the second half of the 20th century, on the other hand, it experienced strong experience in unexpected works that were not always codified as sacred. Burri’s Cretto, Sigmar Polke’s Stained Glass windows in Zurich Cathedral and Gerard Richter’s 72-tone stained glass windows in Cologne Cathedral, Anselm Kiefer’s Celestial Towers at the Hangar Bicocca, and Walter De Maria’s panoramic The Lightnig Field in New Mexico, like the use of pollen in Wolfgang Laib’s work. The spiritual re-proposition of gold in the art of Yves Klein, and in that of James Lee Byers, or in Lucio Fontana’s The End of God. These are only examples, without descending into classical iconography such as that of the cross, witnessed in Brigitte Niedermair’s photograph. Gerard Richter’s Bachelardian candle that even ended up on 1980s vinyl 1980s, Daydream Nation: by Sonic Youth. Seven Magic Mountains’ by Ugo Rondinone in Nevada where the fluorescent chromatism of stone invokes shamanic acts. I repeat that these are just examples, of how the specificity of a linguistic research lands in the sacred or in real cathedrals. Obviously without necessarily being commissioned and/or present in the constituted ‘cathedrals’, but persisting in those of the spirit of the work.

Pd’A: From when you started working in contemporary art to today, how has the art system changed?

C.G.: Every day the system changes, because the modification is uninterrupted both in terms of the way and the new art venues and strategic openings. But everything always remains entrusted to the system and its centralities (Gallery, Artist, Critic, Collector. As well as Institutions and specialised Publishing, when they are present).

Pd’A: What role do socials play and what effect do they have on the art system?

C.G.: Social media have accelerated and expanded knowledge at an accelerated pace. They have expanded apparent knowledge, i.e. an extended and unexpected dissemination of the image, which at the beginning of the new century was called global. Then for their properties of dissemination through the algorithm and their commercial forms and the skilful use of digital professionals as opposed to the amateurish one, they have become both useful platforms and at the same time deceiving and confusing bubbles. In addition to the excessive expenditure of time experienced by all of us. But social media help to bring us closer to knowledge and are a powerful tool that, like any tool, is only useful in their good use.

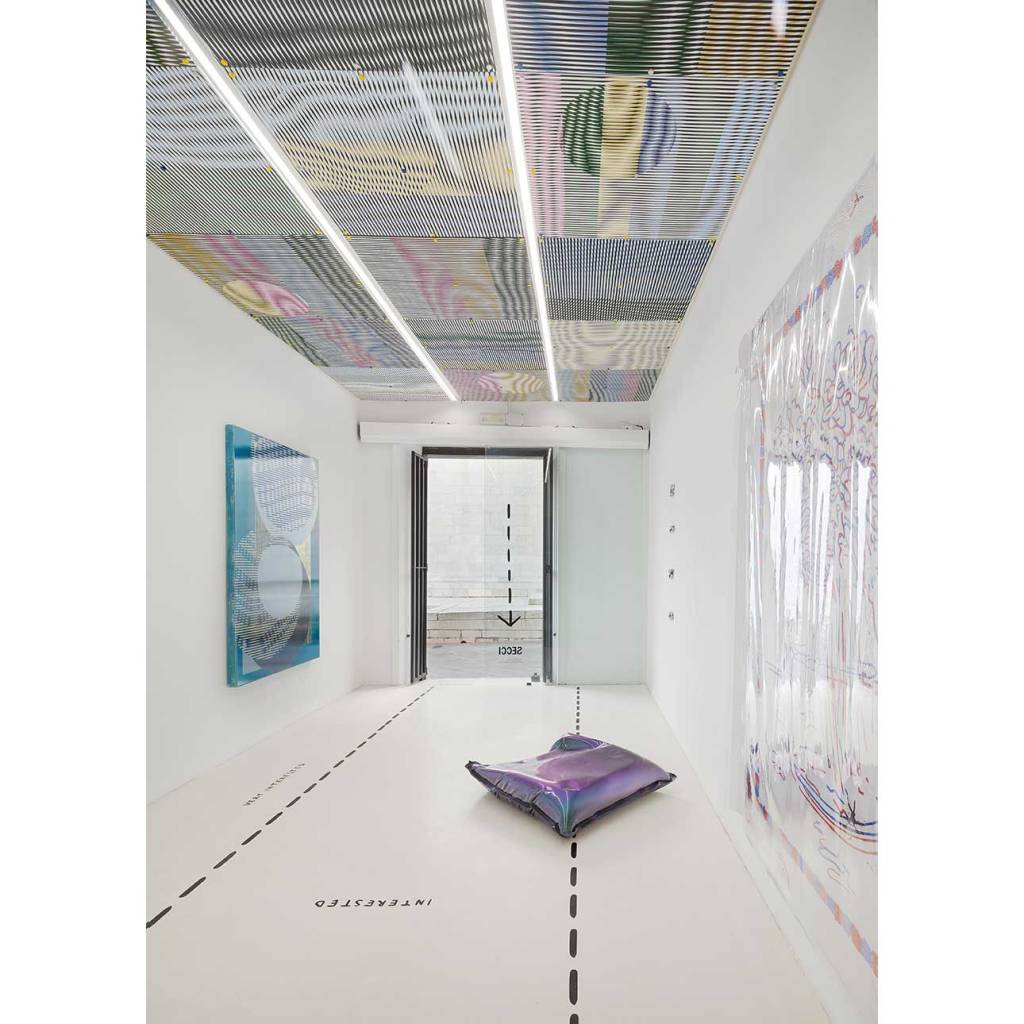

curated by Chiara Guidi,

Secci Gallery, Pietrasanta, 2024, Photo by Nicola Gnesi, Courtesy the Artist and Secci Gallery

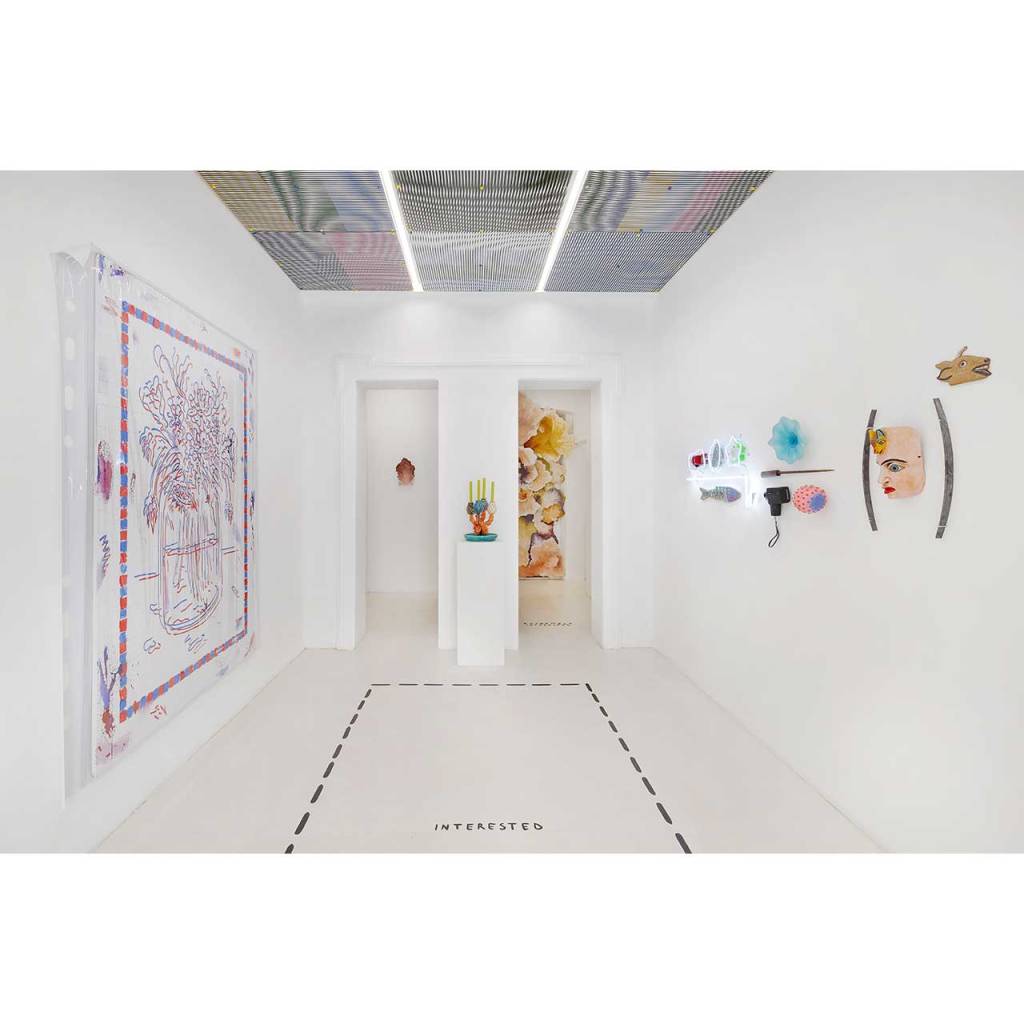

curated by Chiara Guidi, Secci Gallery, Pietrasanta, 2024, Photo by Stefano Maniero,

Courtesy the Artists and Secci Gallery

curated by Chiara Guidi,

Secci Gallery, Pietrasanta 2024, Photo by Stefano Maniero,

Courtesy the Artists and Secci Gallery

Photo by Stefano Maniero,

Courtesy the Artists and Secci Gallery

Courtesy the Artists and Secci Gallery