(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #takakohirai

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui iniziano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di un certo interesse verso l’arte. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Takako Hirai: Penso che giocare nella terra e osservare gli insetti mi abbia avvicinato istintivamente all’arte. Non pensavo a quell’atto come ad un’arte, ma ora ricordare come mi sentivo in quel momento, mi sta aiutando a conoscere me stessa nella creatività. Un altro lato di me, fin da piccola venivo elogiata per essere brava a disegnare ma venivo giudicata che non era da bambina cioè non essere in grado di creare le opere intuitivamente ne emotivamente. E sentivo che questo fosse un mio difetto.

Pd’A: Hai avuto anche tu, come capita a molti, un primo amore artistico, quale?

T.H.: Forse erano gli insetti e le piante stesse ma mi piaceva anche sfogliare i libri come enciclopedie e diari di osservazione, e guardare le loro illustrazioni. Il mio primo amore artistico, o meglio, l’opera che mi ha colpito con la sua filosofia è stata ‘Nausicaä della valle del vento’ di Miyazaki. Anche se ero una bambina di 8 anni sono entrata in empatia con la protagonista..ci ho messo molto tempo per ritornare nel mondo reale.

Pd’A: Quali studi hai fatto?

T.H.: Ho frequentato le lezioni d’arte artigianale per bambini e poi ho iniziato a studiare la pittura ad olio a 13 anni. Ho imparato di più su come usare le matite ad una scuola preparatoria universitaria. Mi sono specializzata in pittura ad olio presso la facoltà di arte della Hiroshima City University dove mi sono laureata. Durante il viaggio scolastico mi hanno impressionato i mosaici in una chiesa di Roma. E qualche anno dopo sono arrivata a Ravenna a studiare la tecnica musiva.

Pd’A: Ci sono statti degli incontri importanti durante la tua formazione?

T.H.: Sì. La maestra di scuola elementare che ha detto di non portare via le pietre dal fiume perché in esse risiedono gli spiriti. Sicuramente il film e fumetti originali di Nausicaä della valle del vento di Miyazaki. Il mosaico parietale di una chiesa(purtroppo non mi ricordo quale)di Roma che mi ha trascinato nel mondo del mosaico. E la mosaicista ravennate Arianna Gallo che ha accettato di insegnarmi il primo mosaico e tanti altri. L’affresco di Madonna del parto di Piero Della Francesca che mi ha fatto tornare ad ammirare ben tre volte. Le opere di Giuseppe Penone che mi hanno risuonato, alla Biennale di Venezia alla quale sono andata per la prima volta. Lo scultore Kan Yasuda che ho conosciuto tramite un’amica, grazie alle sue parole svolte in un periodo importante, sono stata sbloccata da una certa perplessità.

Pd’A: Nel tempo come si è sviluppato il tuo lavoro?

T.H.:All’inizio pensavo di dover esprimere qualcosa utilizzando solo le tecniche che avevo studiato. Tuttavia, sentivo che c ’ era un limite a come potevo dare forma alle visioni della mia immaginazione, quindi ho iniziato a sfidare senza limitare le tecniche e i materiali che potevo

utilizzare. Potrebbe essere una specie di ritorno alle origini, facendo tesoro degli studi e esperienze. Negli ultimi anni mi sono aumentate l ’ interesse e l ’ ispirazione nellea creazione di opera installativa.

Pd’A: Il disegno ha per te una c’erta importanza?

T.H.: sì, mi sembra che utilizzando tecniche del disegno riesco a catturare la interiorità del soggetto, lo spazio trasparente nel suo essere. Mi piace questa sensazione che ricevo.

Pd’A: Quando inizi un lavoro hai già un’idea chiara di come si svilupperà o c ’ è spazio per delle modifiche in corso d’opera?

T.H.:Nella maggior parte dei casi c’è un’immagine chiara del lavoro finito. Ma ultimamente ascolto le mie intuizioni durante il processo di creazione e affronto su di essa mentre procedo con la lavorazione. Prendo del tempo per osservare e fantasticare fino a che arrivo in modo soddisfacente. In precedenza puntavo alla perfezione prima di iniziare a realizzarlo, ma capita spesso che sorgano delle domande durante la produzione, quindi penso che affrontandole apertamente al momento mi avvicini di più a ciò che voglio esprimere.

Pd’A: Ti vorrei chiedere di raccontare la tua idea di natura?

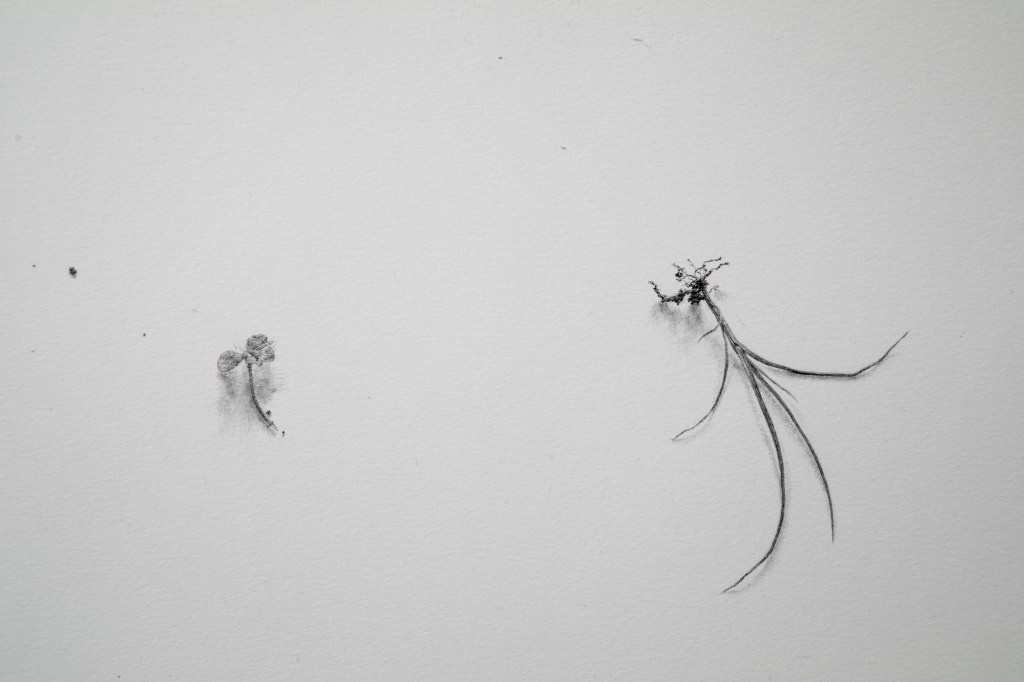

T.H.: Sarebbe atmosfera, sarebbe paesaggio, sarebbe fenomeno. Fondamentalmente la Natura sarebbe dove è libera di nascere, vivere e morire. Nel mio tema sono più interessata però ad affrontare l’essere stesso. Io sono una natura. E la natura di l’essere, che sarebbe come si vive naturale ma anche la morte naturale come essere umano. E poi durante la creatività penso alla Terra. La Natura è la vita della Terra. E io sono una zecca che succhio il suo sangue e stacco i suoi brandelli.

Pd’A: Il tempo è lo spazio che ruolo hanno?

T.H.: questa è solo la mia sensazione e fantasticheria personale. Penso che sia chiaramente uno di loro ruoli portare impermanentemente cambiamento e trasformazione. Senza tempo e spazio non c’ è esistenza né estinzione. Se sì, è una conferma dell’esistenza? Il tempo e lo spazio esistono dove non c’è un’esistenza? In primo luogo non esiterebbe chi potrebbe fare la domanda…avere desiderio di sapere e di essere curioso, fare statistica e definire le cose sono della natura umana. Forse non esiste nessun altri viventi che siano interessati agli altri quanto gli umani. Quando sono sola e quando sono con qualcun altro, sento che il ritmo, la forma e la posizione del tempo e dello spazio sono diversi. In altre parole, ognuno di noi sembra indossare un velo di tempo e spazio diverso. Ciò che riconosciamo come se fossero regolari, limitati e partizionati sono le ore e i luoghi e non è altro che orologi, bilance e metri da nastro necessari per rispettare gli altri esseri e confermare la propria posizione coscientemente. Le cose senza forma sono libere e se qualcuno che ha una forma pensa a loro, il tempo e lo spazio si nascono o vengono donati.

Pd’A: Che importanza attribuisci ai materiali che impieghi ?

T.H.:Sento che è il destino incontrare il materiale stesso. I miei occhi colgono le tracce vissute fino ad ora e mi rendo conto del valore dell’individuo attraverso il tatto e la sensazione, anche in olfatto, e con tutto ciò possibile. I materiali stessi sono spesso la fonte di ispirazione, quindi il tempo trascorso ad osservarli è più lungo del tempo impiegato a realizzare un’opera.

Pd’A: Ti interessa la dimensione spirituale?

T.H.: sì, perché ci sono miracoli che non possono nascere senza la dimensione spirituale. Potrebbe diventare una continuazione del pensiero precedente su tempo e spazio. Tutti abbiamo una dimensione spirituale personale. Penso che ci possano essere differenze in ciò che le persone fanno a seconda che vogliano trarne vantaggio e coloro che non lo ritengono necessario o non ne sono consapevoli. Nel mio esempio, il momento in cui ne divento concentratamente consapevole e in cui chiedo aiuto, è ora di allestire un ’ opera di installazione. Il tempo e lo spazio e la dimensione spirituale. Per me importante creare uno squilibrio affilato e ricercato nello spazio, che crei una certa tensione. E così che prende la vita il lavoro di installazione. La premessa qui è mostrarlo, quindi voglio creare una situazione che possa essere condivisa e risuonante anche per un istante. L’ ideale avvenga una sinergia tra i presenti. A questo punto mi chiedo se sia giusto adattarla al 100% a mio agio o quanto dovrei consapevole della sensibilità del pubblico in generale. Ecco qui mi torna la domanda, cosa sia ‘generale’.

Pd’A: Che cosa succede alle opere quando non c’è nessuno che le osserva, l’esistenza di un opera d’ arte può prescindere dalla presenza di un osservatore?

T.H.: Tutto appare diversamente a seconda di chi la osserva. Allora se nessuno la osserva, potrebbe riuscire a rimanere nella sua vera forma. Succede a me, esco dallo studio pensando di non avere più nulla da aggiungere solo da parte mia a un mio lavoro e quando ci rientro sento una certa presenza e percepisco di non poterlo più toccare. Un senso di presenza evidente che emana dall’opera. È allora che mi rendo conto che l’esistenza di un’opera d’arte ha un senso di autoaffermazione. Le cose sono impermanenti dal momento in cui iniziano ad esistere. Ciò che è bello è che può continuare ad esistere anche nei ricordi e nelle emozioni anche quando non esiste più l’opera.

Pd’A: Secondo te l’artista dove si pone nei confronti della sua opera?

T.H.: Un artista sarebbe l’ artigiano selezionato da un Kami (dei non appartenenti nessuna religione specifica) o il portatore di una sua voce? Oppure un credente o un paziente della propria opera. Voglio lavorare con questa mentalità e voglio dare un rispetto alla propria opera. In ogni caso l’ autore è il primo a vedere l’opera che ha preso forma. A volte finisce per essere l’unico testimone. L ’ autore che decide se pubblicarla o meno. Se questa opera è qualcosa da mostrare sarà la dimensione spirituale a guidarlo.

Takako Hirai è un’artista giapponese nata nel 1975 a Kumamoto in Giappone. Ha studiato pittura a olio alla Hiroshima City University. Il suo lavoro è caratterizzato da una sensibilità per il paesaggio e la natura, spesso esplorati in modo poetico e minimalista, con un forte senso di intimità e silenzio. Hirai si concentra su immagini che sembrano sospese nel tempo, invitando lo spettatore a riflettere sul rapporto tra il soggetto e il contesto, riesce a catturare l’essenza degli ambienti naturali e artificiali, creando atmosfere evocative e meditative. Nel 2003 arriva a Ravenna per studiare la tecnica musiva, dal 2005 ci vive e lavora stabilmente.

English text

Interview to Takako Hirai

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #takakohirai

Parola d’Artista: For most artists, childhood is the golden age when the first signs of an interest in art begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Takako Hirai: I think playing in the dirt and observing insects instinctively brought me closer to art. I didn’t think of that act as art, but now remembering how I felt at the time is helping me to know myself in creativity. Another side of me, even as a child I was praised for being good at drawing but I was judged for not being able to create the works intuitively or emotionally. And I felt that this was a defect of mine.

Pd’A: You also had, as happens to many, a first artistic love, which one?

T.H.: Perhaps it was the insects and plants themselves, but I also liked leafing through books such as encyclopaedias and observation journals, and looking at their illustrations. My first artistic love, or rather, the work that struck me with its philosophy was Miyazaki’s ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’. Even though I was an eight-year-old girl, I empathised with the main character…it took me a long time to return to the real world.

Pd’A: What studies did you do?

T.H.: I attended children’s handicraft classes and then started studying oil painting at the age of 13. I learnt more about how to use pencils at a university preparatory school. I specialised in oil painting at Hiroshima City University’s art faculty where I graduated. During my school trip, I was impressed by the mosaics in a church in Rome. And a few years later I came to Ravenna to study mosaic technique.

Pd’A: Were there any important encounters during your education?

T.H.: Yes. The primary school teacher who said not to take the stones away from the river because spirits reside in them. Definitely the original film and comics of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind by Miyazaki. The wall mosaic of a church (unfortunately I cannot remember which one) in Rome that drew me into the world of mosaics. And the mosaicist from Ravenna, Arianna Gallo, who agreed to teach me the first mosaic and many others. The Madonna del Parto fresco by Piero Della Francesca that made me return to admire it three times. Giuseppe Penone’s works that resonated with me at the Venice Biennale, which I went to for the first time. The sculptor Kan Yasuda whom I met through a friend, thanks to his words during an important period, I was released from a certain perplexity.

Pd’A: How has your work developed over time?

T.H.:At first I thought I had to express something using only the techniques I had studied. However, I felt that there was a limit to how I could shape the visions of my imagination, so I started to challenge without limiting the techniques and materials I could use. It could be a kind of return to my roots, building on my studies and experiences. In recent years, I have become more interested and inspired in creating installation works.

Pd’A: Does drawing have a great importance for you?

T.H.: Yes, I feel that by using drawing techniques I am able to capture the interiority of the subject, the transparent space in its being. I like this feeling I get.

Pd’A: When you start a work, do you already have a clear idea of how it will develop, or is there room for changes as you go along?

T.H.:In most cases there is a clear image of the finished work. But lately I listen to my intuition during the creation process and deal with it as I go along. I take time to observe and fantasise until I arrive in a satisfactory way. Previously I aimed for perfection before I started making it, but it often happens that questions arise during production, so I think that addressing them openly in the moment brings me closer to what I want to express.

Pd’A: I would like to ask you about your idea of nature?

T.H.: It would be atmosphere, it would be landscape, it would be phenomenon. Basically, Nature would be where it is free to be born, live and die. In my theme, however, I am more interested in dealing with being itself. I am nature. And the nature of being, that would be how one lives naturally but also natural death as a human being. And then during creativity I think about the Earth. Nature is the life of the Earth. And I am a tick that sucks its blood and pulls off its shreds.

Pd’A: What role do time and space play?

T.H.: This is just my personal feeling and reverie. I think it is clearly one of their roles to impermanently bring about change and transformation. Without time and space there is no existence or extinction. If so, is this a confirmation of existence? Do time and space exist where there is no existence? In the first place, there would be no one who could ask the question…having a desire to know and being curious, making statistics and defining things are human nature. Perhaps there is no other living being that is as interested in others as humans are. When I am alone and when I am with someone else, I feel that the rhythm, shape and position of time and space are different. In other words, each of us seems to wear a different veil of time and space. What we recognise as regular, limited and partitioned are the hours and places and are nothing more than clocks, scales and tape measures needed to respect other beings and confirm one’s position consciously. Formless things are free and if someone who has a form thinks of them, time and space are born or donated.

Pd’A: What importance do you attach to the materials you use?

T.H.: I feel that it is destiny that meets the material itself. My eyes catch the traces I have experienced so far and I realise the value of the individual through touch and sensation, also in smell, and with everything possible. The materials themselves are often the source of inspiration, so the time spent observing them is longer than the time taken to make a work.

Pd’A: Are you interested in the spiritual dimension?

T.H.: Yes, because there are miracles that cannot come into being without the spiritual dimension. It could become a continuation of previous thinking about time and space. We all have a personal spiritual dimension. I think there can be differences in what people do depending on whether they want to take advantage of it and those who do not think it is necessary or are not aware of it. In my example, the moment I become concentrically aware of it and when I ask for help, it is time to set up an installation. Time and space and the spiritual dimension. For me, it is important to create a sharp and refined imbalance in space, which creates a certain tension. And that is how the installation work comes to life. The premise here is to show it, so I want to create a situation that can be shared and resonant even for a moment. Ideally, there will be a synergy between those present. At this point I ask myself whether I should adapt it 100 per cent at my ease or how aware I should be of the sensibilities of the general public. Here the question comes back to me, what is ‘general’.

Pd’A: What happens to works of art when there is no one there to observe them, can the existence of a work of art be without the presence of an observer?

T.H.: Everything looks different depending on who is observing it. So if nobody observes it, it might be able to remain in its true form. It happens to me, I walk out of the studio thinking I have nothing more to add to my work and when I go back in, I feel a certain presence and sense that I can no longer touch it. A clear sense of presence emanates from the work. It is then that I realise that the existence of a work of art has a sense of self-assertion. Things are impermanent from the moment they begin to exist. What is beautiful is that it can continue to exist in memories and emotions even when the work no longer exists.

Pd’A: Where do you think the artist stands in relation to his work?

T.H.: Would an artist be the craftsman selected by a Kami (gods not belonging to any specific religion) or the bearer of his own voice? Or a believer or a patient of his own work. I want to work with this mentality and I want to give respect to one’s work. In any case, the author is the first to see the work that has taken shape. Sometimes he ends up being the only witness. It is the author who decides whether or not to publish it. If this work is something to be shown, it is the spiritual dimension that will guide him.

Takako Hirai is a Japanese artist born in 1975 in Kumamoto, Japan. She studied oil painting at Hiroshima City University. Her work is characterised by a sensitivity to landscape and nature, often explored in a poetic and minimalist manner, with a strong sense of intimacy and silence. Hirai focuses on images that seem suspended in time, inviting the viewer to reflect on the relationship between subject and context. He manages to capture the essence of natural and man-made environments, creating evocative and meditative atmospheres. In 2003 he arrived in Ravenna to study mosaic technique, and since 2005 he has lived and worked there permanently.

– Brandelli della Terra, 14.5 x 12 x 5.5cm, 2022, cristallo di gesso, malta, pannello di legno

Ph, Marco Parollo

Ph, Marco Parollo

Ph, Marco Parollo

Ph, Marco Parollo

Ph, Giampaolo Solitro

Ph, Takako Hirai