(Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #silviainselvini #artistinterview

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Silvia, anni fa ho intervistato Jan Fabre che mi raccontò di essere affascinato dalla qualità iridescente argentea dell’inchiostro e dal basso costo delle penne a sfera blu. A te che cosa affascina di questo materiale?

Silvia Inselvini: Il fatto che, prima o poi nella vita, tutti abbiamo avuto l’occasione di avere tra le mani una penna a sfera, e per di più blu, è già di per sé molto affascinante. Per quel che mi riguarda, però, credo che l’interesse per l’oggetto-penna-a-sfera, derivi principalmente dalla fascinazione per la scrittura. La lettura è la prima scuola di scrittura, e come per tutte le persone che leggono molto, arriva il momento in cui si prova a cimentarsi anche nello scritto: la cosa più meritevole di attenzione in questa esperienza, è stata poter sperimentare su me stessa come il cervello, in relazione a quello che si legge, assorba modelli, costrutti e stili, per poi riproporli più o meno rielaborati, tuttavia, almeno nel mio caso, con poca autenticità. Quindi, fortunatamente per me e per tutti, mi sono accorta molto velocemente che la scrittura non rientra tra i miei talenti, e che questo mio interesse, più che per lo scrivere narrativo, è rivolto al fatto dello scrivere in sé.

P.d’A.: Che importanza hanno in quello che fai l’idea di intensità e quella di densità?

S.I.: Fra i due concetti, quello a cui probabilmente penso di più è quello di intensità, e nei miei lavori ce n’è molta. Non parlo di intensità lirica o emotiva, quella riguarda, eventualmente, chi guarda l’opera.

Parlo di una intensità energetica, di una intenzione, di un essere-a-fuoco. Quando si passano molte ore a ripetere continuamente lo stesso gesto, con intenzione e attenzione, è naturale che questo generi una particolare intensità e risonanza, che lo differenzia dalla normale routine. Il gesto ripetuto fa sì che il tempo si dilati, e che il presente diventi più vivo.

P.d’A.: Secondo te il sacro ha ancora una sua importanza nell’arte di oggi?

S.I.: Dovrebbe averla, e per me chiaramente ce l’ha. Viviamo in un’epoca in cui si è quasi totalmente perso ogni slancio verticale verso ciò che nella vita c’è di misterioso e sottile, cosa che è in gran parte dovuta alla scomparsa dei riti, che generano un tempo “altro” rispetto al quotidiano, un tempo “elevato”. Col mio lavoro di ripetizione, appunto, rituale, cerco di contrappormi a un presente che io percepisco come svuotato, omologato, accelerato e pericolosamente ego riferito, e di offrire una soglia di ingresso verso un altrove più armonico e aperto, fatto di infinite varianti, intensive e non estensive, per il solo fatto che il gesto manuale, per quanto ripetuto, non è mai identico a se stesso. Come scrisse Kierkegaard: senza la categoria della reminiscenza o della ripetizione, la vita intera svanisce in un rumore vuoto e inconsistente.

P.d’A.: Ti interessa l’idea di messa in scena nel tuo lavoro?

S.I.: Se per messa in scena si intende tutto il processo tramite cui un’opera prende vita, la risposta è sì. E, per me che sono all’interno di quel processo, tutte le azioni che vengono prima dell’effettiva esposizione di un lavoro, sono le cose più interessanti. Innanzi tutto, il gesto si evolve e cambia, ed è molto curioso accorgersi di come la mano, citando Tullio Pericoli, abbia una sua sapienza e un suo metodo indipendente dal nostro controllo. Poi, ciò che tuttora mi diverte di più, è la parte compositiva, che è molto meno lineare di quello che si è portati a pensare. Prima di tutto realizzo i fogli, uno dietro l’altro: passo anche dei mesi a fare solo quelli. Poi, quando ne ho anche diverse centinaia, arriva il momento della composizione, ed è a quel punto che scopro che non tutti i fogli accostati “funzionano”: può capitare, quindi, che all’interno di uno stesso pannello siano affiancati fogli realizzati giorni prima e fogli realizzati a mesi di distanza, e la cosa ogni volta mi emoziona, perché rende ancora più evidente la circolarità del tempo e la condensazione tra passato, presente e futuro.

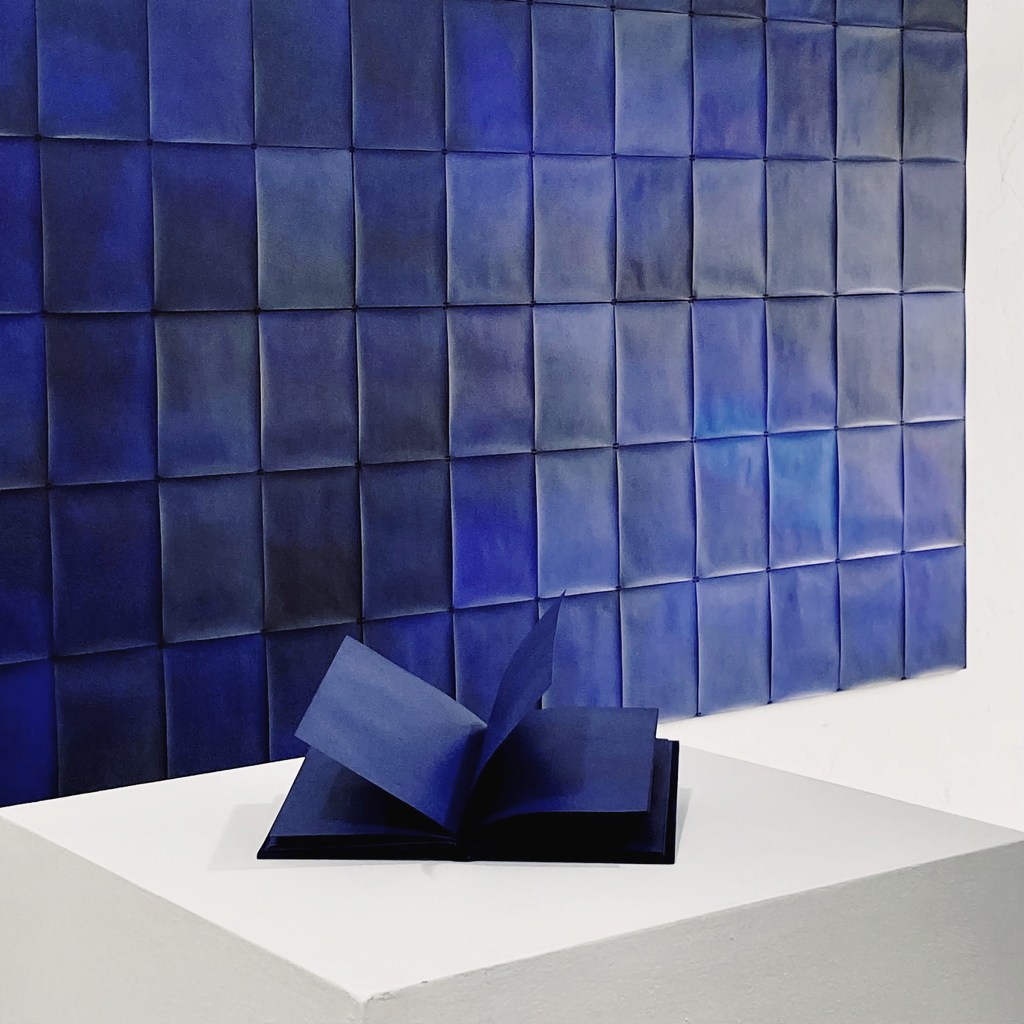

P.d’A.: Per quale motivo i tuoi lavori si compongono spesso di diversi fogli accostati fra loro?

S.I.: Il motivo è, in un certo senso, puramente tecnico: il foglio A4 è un formato che riesco a iniziare e finire in un’unica sessione di lavoro, senza interruzioni. Quando ho provato a lavorare su formati più grandi, per forza di cose arriva un momento in cui devo fare una pausa. E, in quella pausa, per quanto breve, l’inchiostro si asciuga, e quando ricomincio a lavorare, nel punto dove i nuovi tratti si sovrappongono a quelli asciugati, si forma come una specie di striscia più cangiante, che mette in evidenza il fatto che il lavoro non è stato continuativo, ma ha subìto un’interruzione: una specie di “giornata”, come nell’affresco. Questo aspetto va sicuramente tenuto in considerazione, ma al momento non mi interessa integrarlo nei miei lavori. Un cambio formale, implica conseguenze anche in termini di struttura concettuale e di lettura del lavoro. Ho bisogno di rifletterci ancora, prima di inserire questa variazione.

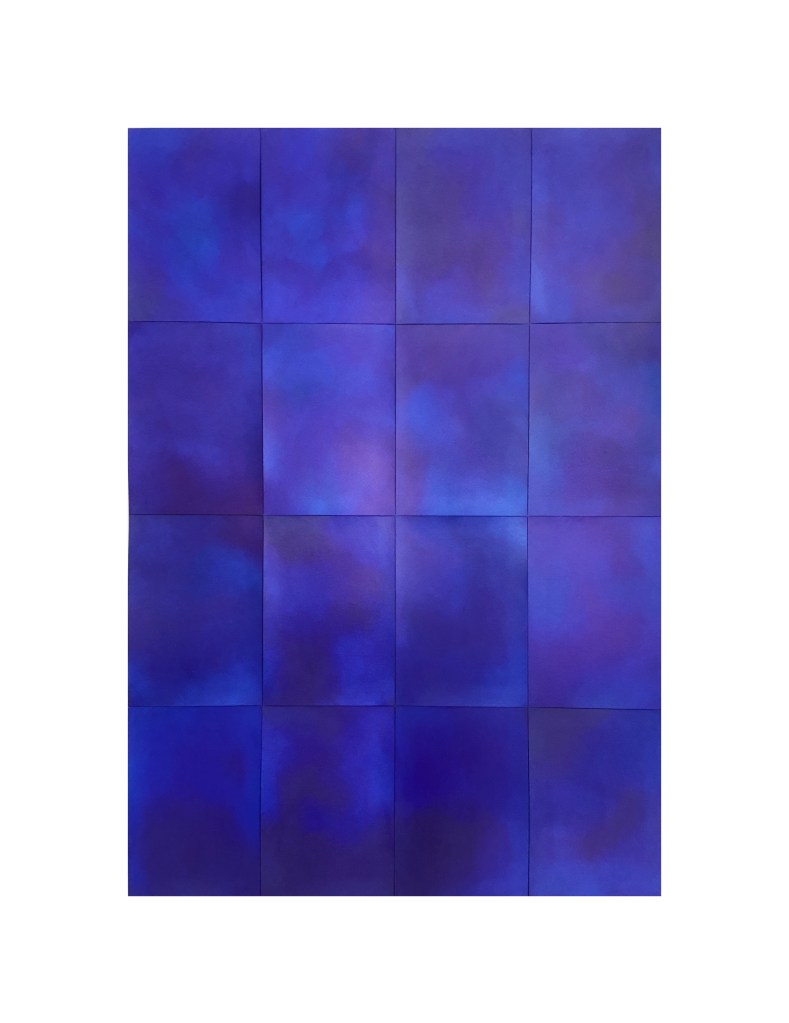

P.d’A.: Questi lavori fatti con la penna a sfera su carta sono dei disegni per te?

S.I.: Non li ho mai pensati come disegni, ma come veri e proprio lavori di pittura con delle componenti scultoree, per via dei movimenti naturali della carta.

Questo materiale riesci a fissarlo?

S.I.: Nei primi lavori, il fissaggio era volutamente provvisorio: usavo lastre di metallo e magneti piccolissimi, e ogni volta che si presentava l’occasione di una esposizione, il lavoro andava montato, e poi smontato. Tutto questo perché non volevo bucare i fogli o incollarli come fossero dei poster. Col passare degli anni, e dopo vari tentativi, ho trovato una colla da restauro che non rovina i fogli, e li fisso su dei telai su cui faccio montare del cartoncino museale, ma solo sugli angoli, in modo che abbiano un minimo di libertà di movimento, dato dai cambi di temperatura e umidità. In questo modo, il lavoro mantiene, come ho detto nella risposta precedente, anche il suo aspetto scultoreo.

Quando non c’è nessuno che la osserva l’opera secondo te continua ad esistere?

S.I.: Mi piacerebbe molto fosse possibile, ma credo di no. Lessi anni fa, non ricordo dove, ma ricordo mi rimase molto impresso, un piccolo estratto di un’intervista a Mark Rothko, dove si trattava esattamente la questione. Rothko sostiene – riporto al presente, data la contemporaneità del pensiero espresso – che un’opera non può vivere nell’isolamento, ha bisogno di uno sguardo per vivere ed anche per poter crescere, in un certo senso. Tuttavia, ogni volta che si consegna la propria opera al mondo, bisogna essere consapevoli di star compiendo un gesto (sono certa gli aggettivi fossero questi) “rischioso e spietato”, perché capiterà molto spesso, e a maggior ragione oggi che ci sovraesponiamo volontariamente e in modo sistematico, che il nostro lavoro verrà offeso da sguardi impreparati, e quindi potenzialmente crudeli.

Trovo anche molto bello il porre l’attenzione sul fatto che tutta la nostra compassione debba andare verso il lavoro che subisce questo sguardi, non al nostro ego, che potrebbe venir ferito da qualche commento negativo.

Silvia Inselvini (Brescia, 1987)

Tra le ultime mostre ricordiamo: “24! Questions for the Concrete Art”, Museo d’Arte Concreta di Ingolstadt, Germania (2024), collettiva, “Il Crepuscolo degli Uomini”, Museo d’Arte Nazionale di Cluj-Napoca, Romania (2023), personale; Collettiva dei finalisti del Premio VAF IX, Castello Estense di Ferrara (2023) e Stadtgalerie di Kiel, Germania (2021); “Take your time”, Triennale di Tongyeong in Corea del Sud (2022) collettiva; “Anàstasi”, Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Pietrasanta (2022) collettiva; “The colour out of space”, Galerie Isabelle Lesmeister, Regensburg (2021) personale; “Eadem mutata resurgo” e “Rivelazioni”, IAGA Contemporary Art, Cluj-Napoca, Romania (2016 e 2019), personali.

English text

Artist interview Silvia Inselvini

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #silviainselvini #artistinterview

Parola d’Artista: Hi Silvia, years ago I interviewed Jan Fabre who told me he was fascinated by the iridescent silvery quality of ink and the low cost of blue ballpoint pens. What fascinates you about this material?

Silvia Inselvini: The fact that, sooner or later in life, we have all had the opportunity to have a biro in our hands, and a blue one at that, is in itself a very fascinating fact. As far as I am concerned, however, I believe that the interest in the ballpoint pen-object stems mainly from a fascination with writing. Reading is the first school of writing, and as for all people who read a lot, there comes a time when they try their hand at writing as well: the most noteworthy thing about this experience was being able to experiment on myself how the brain, in relation to what one reads, absorbs models, constructs and styles, and then re-processes them more or less, however, at least in my case, with little authenticity. So, fortunately for me and for everyone else, I realised very quickly that writing is not one of my talents, and that this interest of mine, rather than narrative writing, is directed towards the fact of writing itself.

P.d’A.: How important are the ideas of intensity and density in what you do?

S.I.: Of the two concepts, the one I probably think of most is that of intensity, and there is a lot of that in my work. I am not talking about lyrical or emotional intensity, that concerns, eventually, the person looking at the work.

I’m talking about an energetic intensity, an intention, a being-at-fire. When one spends many hours continuously repeating the same gesture, with intention and attention, it is natural that this generates a particular intensity and resonance, which differentiates it from normal routine. The repeated gesture makes time dilate, and the present becomes more vivid.

P.d’A.: In your opinion, does the sacred still have an importance in today’s art?

S.I.: It should have it, and for me it clearly does. We live in an era in which we have almost totally lost any vertical impulse towards what is mysterious and so4le in life, which is largely due to the disappearance of rituals, which generate a time “other” than the everyday, a time “elevated”. With my work of repetition, precisely, ritual, I try to counteract a present that I perceive as emptied, homologated, accelerated and dangerously ego-referenced, and to offer a threshold of entry towards a more harmonious and open elsewhere, made up of infinite variants, intensive and not extensive, for the mere fact that the manual gesture, however repeated, is never identical to itself. As Kierkegaard wrote: Without the category of reminiscence or repetition, the whole life fades into an empty, insubstantial noise.

P.d’A.: Are you interested in the idea of staging in your work?

S.I.: If by staging you mean the whole process by which a work comes to life, the answer is yes. And, for me, being inside that process, all the actions that come before the actual staging of a work are the most interesting things. First of all, the gesture evolves and changes, and it is very curious to realise how the hand, quoting Tullio Pericoli, has its own wisdom and method independent of our control. Then, what I still enjoy most is the composition part, which is much less linear than one is led to think. First of all, I make the sheets, one after the other: I also spend months making just those. Then, when I have several hundred of them, the moment of composition arrives, and it is at that point that I discover that not all the sheets put side by side “work”: it can happen, therefore, that within the same panel there are sheets made days before and sheets made months later, and this always excites me, because it makes the circularity of time and the condensation between past, present and future even more evident.

P.d’A.: Why do your works often consist of several sheets placed side by side?

S.I.: The reason is, in a way, purely technical: the A4 sheet is a format that I can start and finish in a single work session, without interruptions. When I try to work on larger formats, there comes a time when I have to take a break. And, in that pause, however brief, the ink dries, and when I start working again, at the point where the new strokes overlap the dried ones, a kind of more iridescent streak forms, which highlights the fact that the work has not been continuous, but has undergone an interruption: a kind of ‘day’, as in the fresco. This aspect must certainly be taken into account, but at the moment I am not interested in integrating it into my work. A formal change also implies consequences in terms of the conceptual structure and reading of the work. I need to think about it some more before incorporating this variation.

P.d’A.: Are these biros works on paper drawings for you?

S.I.: I never thought of them as drawings, but as real paintings with sculptural components, because of the natural movement of the paper.

P.d’A.: Can you fix this material?

S.I.: In the early works, the fixing was deliberately provisional: I used metal sheets and very small magnets, and every time the opportunity for an exhibition arose, the work had to be mounted, and then taken down. All this because I didn’t want to puncture the sheets or glue them like posters. Over the years, and after several attempts, I found a restoration glue that does not ruin the sheets, and I fix them on frames to which I have museum cardboard mounted, but only on the corners, so that they have a minimum of freedom of movement, given by changes in temperature and humidity. In this way, the work also retains, as I said in the previous answer, its sculptural appearance.

P.d’A.: When there is no one observing it, does the work continue to exist in your opinion?

S.I.: I would love it if it were possible, but I guess not. I read years ago, I don’t remember where, but I remember it stayed with me a lot, a small extract from an interview with Mark Rothko, where exactly this question was discussed. Rothko argues – I bring it back to the present, given the contemporaneity of the thought expressed – that a work cannot live in isolation, it needs a gaze to live and also to be able to grow, in a certain sense. However, every time you hand your work over to the world, you have to be aware that you are making a gesture (I am sure the agge4ves were this) that is “risky and ruthless”, because it will happen very often, and all the more so now that we overexpose ourselves voluntarily and systematically, that our work will be offended by unprepared, and therefore potentially cruel, gazes.

I also find it very nice to point out that all our compassion should go to the work that suffers these stares, not to our ego, which might be hurt by some negative comment.

Silvia Inselvini (Brescia, 1987)

Recent exhibitions include: ’24! Questions for the Concrete Art’, Museum of Concrete Art in Ingolstadt, Germany (2024), group show; ‘The Twilight of Men’, National Art Museum in Cluj-Napoca, Romania (2023), solo show; ‘Collective of the finalists of the VAF IX Prize’, Castello Estense in Ferrara (2023) and Stadtgalerie in Kiel, Germany (2021); ‘Take your time’, Tongyeong Triennale in South Korea (2022) group show; ‘Anàstasi’, Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Pietrasanta (2022) group show; ‘The colour out of space’, Galerie Isabelle Lesmeister, Regensburg (2021) solo show; ‘Eadem mutata resurgo’ and ‘Revelations’, IAGA Contemporary Art, Cluj-Napoca, Romania (2016 and 2019), solo shows.