(Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistacuratore #intervistaartista #curetorinterview #riccardofarinelli

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Riccardo, per molti artisti l’infanzia coincide con il primo manifestarsi dei sintomi di appartenenza al mondo dell’arte è stato così anche per te? Racconta…

Riccardo Farinelli: Ciao, per rispondere adeguatamente alla tua domanda devo far riferimento ad un ricordo d’infanzia ancora molto vivido nella mia memoria. Sperando di non annoiarti, provo a riferirtelo. Un giorno mia madre, esasperata dall’avermi fra i piedi mentre preparava la tavola, mi mise davanti un foglio di quaderno a quadretti e una matita invitandomi a disegnare qualcosa. Non sapevo come procedere e chiesi cosa avessi dovuto disegnare. Mia madre rispose di mettermi in giro per casa e decidere quale oggetto fosse più interessante e poi procedere a disegnarlo. Decisi che l’oggetto più interessante per me era una racchetta da tennis appesa alla parete e quello fu il mio primo disegno eseguito in piena coscienza. Avevo circa 5/6 anni e nel mentre mi concentravo per cogliere tutti i particolari di quell’oggetto, capii che avevo trovato il modo, io bambino che parlava poco, di comprendere e dialogare con il mondo proponendo visioni che le mie parole infantili non erano in grado di esprimere. Compresi confusamente ma con sentimento sicuro che il disegno era il mio linguaggio preferito.

P.d’A.: A questo primo disegno ne sono seguiti molti altri suppongo, questo ti ha portato poi a indirizzare i tuoi studi nel campo artistico o il tuo iter formativo si è mosso in altri territori?

R.F.: Il disegno è stato una presenza costante negli anni seguenti a quella scoperta, disegnavo in ogni occasione e su qualunque pezzo di carta mi capitasse sotto mano. Quando decisi di frequentare il liceo artistico e poi l’Accademia di Belle Arti, imparai ad organizzarmi meglio: avevo, ed ho tutt’ora, sempre con me un blocco o un quaderno da disegno e una matita o un pennarello.

Negli anni dell’Accademia capii anche che erano importanti per me il dialogo con i miei simili, l’impatto che il mio lavoro d’artista produceva in chi lo guardasse e la percezione che l’essere contemporanei significava essere gli ultimi di una lunga serie di generazioni, che rimanevano scritte nella nostra memoria collettiva. Questo doppio sentimento mi ha portato, iniziando proprio da quegli anni, ad approfondire ed affinare i miei mezzi espressivi ma anche ad interessarmi a quella che si definisce divulgazione e formazione. Contemporaneamente cercavo conferme e stimoli nelle ricerche artistiche più aggiornate ma anche nello studio non stereotipato del passato, che ha fatto di me un disegnatore archeologico molto apprezzato. Ho seguito infatti direttamente sul campo campagne di scavo etrusche e preistoriche per circa venti anni, attività che ho dovuto interrompere quando decisi di lavorare al Centro Pecci di Prato.

P.d’A.: Ti volevo ancora chiedere qualcosa riguardo a gli anni della tua formazione. Per prima cosa hai avuto un tuo “Primo Amore” artistico un’opera o un artista che ha ulteriormente acceso il tuo interesse?

Ci sono stati degli incontri importanti negli anni della tua formazione?

R.F.: Mi è difficile rispondere a questa tua domanda, nel senso che non riesco a isolare una sola opera o un solo artista, in quegli anni mi arrivava tutto addosso e niente mi pareva di poco conto. Dovendo scegliere direi che il mio “Primo Amore” artistico è stato doppio: mi colpì moltissimo ad esempio la “Vergine delle Rocce” di Leonardo da Vinci della quale avvertivo il fascino abissale, ma anche “Golconda” di Magritte il cui procedimento straniante mi introduceva ai percorsi della mente ed anche alla attenzione alla struttura linguistica dell’immagine, ai suoi significati più profondi. Quelle due opere e i loro autori mi hanno molto aiutato. E non solo in senso professionale ma anche nell’impostazione mentale in riguardo alle cose del mondo. Poi si, alcuni incontri fatti hanno ulteriormente arricchito il mio sentire artistico, come ad esempio l’incontro con Vedova, Vespignani, Munari aiutandomi anche a comprendere definitivamente come l’arte contemporanea non abbia, come nel passato, un pensiero dominante, in grado di strutturare uno stile coerente che la faccia riconoscere. Tutto quindi si gioca sull’intensità del sentire e sulla profondità della ricerca. Questo fa si che l’arte contemporanea possa dispiegarsi a trecentosessanta gradi, rendendone non di rado difficile la comprensione. La troppa varietà di scelta può sconcertare. Ma il discorso è proprio questo: la scelta non deve avvenire sulla base dello stile o dei modi scelti dall’artista ma sulla capacità empatica che la sua ricerca e la sua sensibilità riesce ad avere nell’impatto visivo con il pubblico. Queste informazioni, acquisite in quegli anni, si sono definitivamente fissate nella mia mente, portandomi a lavorare con eguale impegno e con naturalezza in varie attività, rendendo difficile la mia catalogazione professionale: cosa sono, un pittore, un insegnante, un ricercatore, un operatore culturale, un organizzatore, un curatore? Io stesso trovo difficile rispondere e, infine, ho smesso di chiedermelo.

P.d’A.: Ecco partiamo da questo punto per esplorare più da vicino il tuo lavoro. Nella risposta precedente dicevi che hai lavorato prima come disegnatore archeologico, seguendo importanti campagne di scavo, a tal proposito ti volevo chiedere come mai, ancora oggi, in quest’ambito si preferisce il disegno alla fotografia?

In che modo questa attività si è ripercossa nel tuo lavoro successivo?

R.F.: Si, l’attività di disegnatore archeologico la portavo avanti in parallelo a quella di pittore. Capisco che possa sembrare strano, addirittura anacronistico, il fatto che in ambito archeologico si preferisca il disegno alla fotografia. Il fatto è che la questione è molto pratica: la fotografia, la sua buona resa, è strettamente connessa agli agenti atmosferici. Se ad esempio c’è poca luce, oppure troppa, i dati documentativi risultano falsati e poco attendibili. Il disegno su carta millimetrata invece è attendibile sempre, in qualunque situazione climatica. Inoltre è possibile relazionare fra loro i vari pezzi che emergono dalla terra, così da avere una pianta generale sempre attendibile e aggiornata, sia in orizzontale che in verticale (ovvero in profondità).

La suggestione dell’archeologia sulla mia attività di pittore e, più in generale, in quella di formatore, divulgatore e organizzatore non è di poco conto. Direi che risiede nella motivazione che mi fece a suo tempo avvicinare a quel mondo. Quando, sfacciatamente, mi presentai al direttore di scavo la prima volta il mio obiettivo era quello di essere a contatto con la storia. E non per modo di dire ma concretamente, estraendo da sotto il suolo che i contemporanei calpestano le tracce del passato, vedere la profondità alla quale si trovano che è poi la resa plastica della distanza temporale da noi. Osservare quegli oggetti, vederli apparire nella terra è una emozione molto forte che a me è servita per ricordare sempre che il contemporaneo non è figlio di nessuno, ha i suoi perché più profondi nella storia degli antenati.

P.d’A.: Era un tuo modo per trovare le tue origini, le tue motivazioni?

R.F.: Più che le mie origini, direi ricercare le ragioni profonde dell’esistenza dell’arte, particolarmente in un periodo storico come quello presente che sembra tutto proiettato sul profitto, mettendo in ombra, o addirittura negando, tutto il resto. Questo ai miei occhi significava la morte dell’arte, la quale non soltanto non vive senza una forte motivazione collettiva ma, addirittura, produce un qualcosa (l’opera d’arte) che in una logica di immediata praticità appare del tutto inservibile e inutile. Era necessario quindi recuperare sensi e significati che si erano persi per strada. Questo era il sentimento che mi guidava. Credo di essere rimasto fedele a quel sentire ancora oggi. Nell’attività di pittore questo ha significato recuperare il pieno valore del disegno, base operativa e teorica della scuola toscana; l’uso del monocromo, che utilizzo da qualche anno, valorizza questo aspetto. Nel lavoro di divulgatore e curatore quel pensiero mi ha portato a valorizzare il rapporto del progetto artistico con lo spazio che lo ospita, evidenziando un dialogo serrato che trovo ci sia sempre stato tra la singola personalità dell’artista e la collettività dentro la quale egli è immerso. È questo un punto di vista che vedo stimola e interessa tanto gli artisti quanto il pubblico che ne fruisce.

P.d’A.: Nella risposta sul disegno archeologico dicevi che hai interrotto questa attività per iniziare l’attività legata al Dipartimento Educazione presso il Museo Pecci. Come sei approdato a questa esperienza e che cosa ti ha spinto ad intraprenderla.

R.F.: Al tempo, fine anni 70 inizio anni 80, ero fra quelli che seguivano da vicino il dibattito in città sul Centro Pecci, quando ancora fisicamente neanche esisteva. Quando infine è diventato una struttura conclusa ho pensato che sarebbe stato bello unire la vicinanza all’arte contemporanea con il piacere di farne conoscere regole e contenuti, consentendomi di stare sulla soglia fra quei due mondi. Così mi sono presentato al concorso che fu indetto per il Dipartimento Educazione. In graduatoria risultai primo e fui assunto. È così cominciato un periodo molto interessante per me, dove avevo il tempo di studiare il lavoro degli artisti che via via si succedevano nelle sale e, al contempo, studiare modi per trasmettere i contenuti del loro lavoro al pubblico. L’incontro durato tre anni con Bruno Munari, che periodicamente supervisionava il lavoro svolto in laboratorio, è stato impagabile. Grazie a lui ho definitivamente compreso la necessità del rigore sul lavoro, proposto con gentilezza. Una versione positiva del detto “pugno di ferro in guanti di velluto”. Il mio disegno nascosto era quello di creare, nel tempo, un pubblico per l’arte, tale da poterne allargare la fruizione e il godimento ad un numero maggiore di persone, così da favorirne l’uscita dall’asfissia per carenza di ossigeno. Pericolo a mio parere tutt’ora ben presente. Non avevo previsto che quel tipo di lavoro fosse così tanto impegnativo da impedirmi altre attività che pure amavo.

P.d’A.: Si è vero la didattica fagocita tutto e ti svuota completamente le pile. Per quanto tempo è andata avanti la tua attività al Pecci e di quali aspetti ti occupavi nell’ambito del Dipartimento Educazione?

R.F.: La mia attività al Centro Pecci è andata avanti per ventisei anni. Particolarmente negli ultimi anni, ero responsabile dei progetti relativi alle attività rivolte al pubblico. Il che significava rivedere, riscrivere e riprogettare tutto (conferenze, visite guidate, laboratori) ad ogni cambio di opere nelle sale espositive. C’era poi una attività di corsi e conferenze sulla metodologia di approccio, che mi veniva richiesta da altre istituzioni culturali e formative (musei, associazioni, accademie di Belle Arti, direzioni scolastiche, ecc.); c’era infine il lavoro di documentazione e sistematizzazione del lavoro svolto, utile per la riprogettazione delle attività. Ero anche coordinatore del Dipartimento Cultura, che riuniva Il Dipartimento Educazione e la Biblioteca specializzata interna al Centro, a quel tempo l’unica in Italia di quella ampiezza.

P.d’A.: E il tuo lavoro d’artista in questi anni è proseguito o hai dovuto metterlo da parte?

R.F.: Non riesco a pensare a me stesso senza disegnare e dipingere, dunque ho continuato a farlo. Certamente la mia presenza pubblica da artista è stata in quegli anni meno assidua, decisamente rallentata. Tuttavia grazie al lavoro costante al Centro Pecci, la vicinanza all’arte contemporanea di alto profilo e lo studio degli autori, il mio lavoro d’artista si è consolidato trovando nuovi stimoli di riflessione sulle scelte formali fatte a suo tempo, che non ho mai negato. Poi il contatto frequente con il pubblico mi ha permesso di capirne meglio gli atteggiamenti nei riguardi dell’arte, notare sfumature che mi hanno consentito di affinare i miei strumenti tecnici e tentare modi non banali di approccio, non solo in senso visivo.

P.d’A.: L’attività curatoriale è in qualche modo figlia della tua esperienza didattico/divulgativa?

R.F.: In qualche modo si, nel senso che l’attività curatoriale fa parte di un disegno più complessivo che, nella mia mente almeno, ricostruisce (o prova a ricostruire) la triangolazione positiva tra artista-opera-pubblico. Una questione che occupa la mia mente fin dai miei esordi nel mondo dell’arte. Non è stato difficile infatti comprendere fin dalle prime mostre fatte che il mondo dell’arte è fatto di molti stereotipi e poche persone. Ho sempre pensato che questo non aiutasse ma appesantisse il lavoro degli artisti. L’arte contemporanea, fin dalle avanguardie, ha lavorato molto per togliere gli stereotipi dal giudizio del pubblico ma non pare aver sortito grandi risultati. Per di più, l’auspicato allargamento della fruizione non è avvenuto o, quando è avvenuto, ha preso la forma mostruosa del turismo di massa il quale, letteralmente, consuma senza comprendere. Ho pensato che dovevo provare, nel mio piccolo, a togliere l’artista e il suo lavoro dall’assedio, farlo sentire meno solo nella sua ricerca. Ho cercato, come direbbe Klein, di evidenziare la necessità della condivisione e dell’empatia nell’avvicinarsi al lavoro degli artisti. Questi concetti sono da sempre alla base della mia attività di curatore, che negli ultimi anni ho calato nella realtà fisica organizzando esposizioni in luoghi non deputati ma significativi e fortemente caratterizzati, che gli artisti sono invitati ad interpretare. Ne sono un esempio le esposizioni curate presso la settecentesca Villa Rospigliosi di Prato ma anche quelle che ho chiamato “Arte di confine” e “Arte nei cimiteri”, due progetti espositivi dove il luogo è decisamente non convenzionale ma capace, credo, di stimolare domande e confronti. E questo è il criterio che da sempre guida anche la mia attività di didatta e divulgatore: accompagnare il cittadino/spettatore alla scoperta della viva sostanza dell’opera d’arte e non a mettere in elenco passivamente una serie di informazioni.

P.d’A.: I tre progetti che racconti qui sopra ti vedono coinvolto anche come artista, come riesci a conciliare le due facce della tua attività?

R.F.: Quando penso ad un nuovo progetto espositivo, lo immagino prima di tutto per me stesso, come stimolo alla mia curiosità, nel tentativo di un dialogo non ingessato. Anche per questo quei progetti che ho nominato hanno scenari così inconsueti. Le opere che produco per quel determinato progetto, rappresentano in qualche modo un tentativo di risposta. Sono fra coloro i quali credono che l’artista, da solo, non basti a se stesso. Poi mi viene da pensare che potrebbe essere stimolante anche per alcuni degli artisti che mi è capitato di conoscere, così glielo propongo e, se credono, accettano e ne discutiamo. Mi viene infine abbastanza naturale pensare di scrivere qualcosa che possa aiutare a comprenderne le scelte. Immagino sempre il lavoro dell’artista come contributo non definitivo intorno ad un punto di domanda o ad una suggestione. Dopo tutto, la mia vera ossessione resta il pubblico. Senza di esso l’arte sarebbe niente. Aggiungo anzi che non solo le persone, ogni singolo individuo, sono indispensabili all’arte ma anche ne rappresentano lo stimolo, sempre rinnovato, a produrre opere. La centralità del pubblico l’aveva ben compresa Duchamp, che a tal proposito ha detto parole chiare. Sempre lui aveva giustamente combattuto contro lo sguardo stereotipato, avendone capito il potere di bloccaggio di ogni flusso informativo dall’opera al riguardante. Penso di essere d’accordo con lui e condivido quelle sue idee.

P.d’A.: Nel tuo lavoro che importanza ha il dialogo con i luoghi?

R.F.: Ne ha molta e per molteplici motivi. Il primo di questi è l’aver capito che un luogo, un ambiente non è neutro, emana un suo proprio racconto e penso che un artista debba tenerlo presente. Siamo forse troppo abituati a pensare l’opera nello spazio di una galleria, che cerca spesso di essere più neutro possibile, per considerare fino in fondo questo aspetto. Invece l’ambiente, il luogo condiziona positivamente il lavoro dell’artista, fin quasi a stabilire la dimensione dell’opera, il suo formato, i medium da utilizzare. Poi vale anche come metafora del dialogo necessario e indispensabile che l’opera intrattiene con gli esseri umani, del presente come del passato. L’opera d’arte non è un mondo chiuso, impermeabile al mondo.

P.d’A.: Che rapporto esiste fra il tuo lavoro d’artista e le categorie di tempo e spazio?

R.F.: Dipende da che punto di vista lo intendi. Da quello che possiamo definire operativo il tempo lo intendo come un dialogo continuo tra quella che è la mia memoria personale (tempo individuale) e quella che invece si dilata nella storia (tempo collettivo). Un incontro sempre proficuo e mai in esaurimento, che mi stimola a continuare a dare senso non stereotipato a modi formali consolidati. Questo significa non liquidare con troppa fretta quanto proviene dal passato ma cercare di rimeditarlo alla luce del presente. È quello che mi accade con il disegno ad esempio, del quale avverto la possibilità di una sintesi importante fra la storia e la sensibilità contemporanea. Il lavorare in monocromo ne è stata la logica conseguenza. Sempre da un punto di vista operativo, lo spazio lo intendo limitato al formato che scelgo. So bene che posso, se voglio, farci entrare dentro tutto lo spazio che desidero. È il vantaggio di lavorare nell’ambito della rappresentazione, un universo del quale gli artisti dell’immagine dovrebbero essere ben coscienti.

P.d’A.: Quando lavori con altri artisti quali sono i criteri che adotti per individuare chi coinvolgere?

R.F.: Il primo criterio è il lavoro, ovvero ciò che già conosco di un determinato artista. Questo mi aiuta molto nella scelta, la quale è condizionata anche dalla compatibilità con il progetto che ho in mente. Cerco infatti di coinvolgere artisti il cui lavoro valorizzi il progetto, spesso pensato in primo luogo per un pubblico vasto, ma anche il loro proprio modo di essere artisti, presentandone al pubblico risvolti inconsueti. Cosa questa che non avverrebbe se la scelta fosse casuale, dettata magari da sola simpatia e stima. Ad esempio tutti gli artisti che ho invitato per il progetto “Arte nei cimiteri”, che presupponeva un lavoro site specific, ho sinceramente pensato che avrebbero dato ciascuno uno stimolante contributo ai significati di quel progetto, il quale intendeva far dialogare il mondo dei defunti con quello dei viventi, ovvero tentar di rimuovere l’allontanamento collettivo dal sentimento di mancanza e di fine vita, modalità così presente nel contemporaneo. Intenzione non facile da interpretare, considerando che il luogo era proprio uno spazio all’interno del cimitero di Chiesanuova a Prato. Ho potuto constatare, anche in quella occasione, che sia il presentare argomentazioni fuori dalla norma sia l’uscita dai soliti luoghi, i così detti luoghi deputati, risulta stimolante per il pubblico ma anche per gli artisti.

P.d’A.: Uno dei tuoi progetti prevede l’intervento da parte degli artisti lungo una via di transito intenso di automobili. Questo progetto oltre al luogo non deputato impone per la natura del luogo un tempo di fruizione estremamente limitato, poche frazioni di secondo. Credi che chi si trova a passare davanti ad interventi del genere, senza saperne nulla, sia davvero in grado di accorgersi che quello che ha davanti in quel momento è un’opera d’arte?

R.F.: Direi che quel progetto, tutt’ora in opera nonostante esista da quasi cinque anni, scommette su più livelli: il confronto diretto con l’immagine pubblicitaria, alla quale “ruba” spazio e, appunto, i tempi di fruizione. Se, nonostante tutto, la mia serie di tre gonfaloni riesce a stimolare una riflessione, un pensiero, mi ritengo soddisfatto. In fondo è questo che distingue l’opera d’arte da una immagine pubblicitaria: il riuscire a innescare un processo mentale attivo e critico, capace di attivare domande e riflessioni, mentre l’altra ha l’unico obiettivo di convincere a comprare. Se chi ne fruisce sul momento non si avvede del cambio di registro, ne ha comunque usufruito e questo darà i suoi frutti. L’importante è insistere, visto che credo occorra molto tempo e una strategia continua e costante per poter spuntare qualche risultato. Certo un progetto di quel tipo costringe anche l’artista a riorganizzare i propri mezzi espressivi, renderli più idonei ad una fruizione urbana molto veloce. La scelta dell’artista giusto è, con tutta evidenza, molto importante. Lo è nel caso di “arte di confine” ma anche per tutti gli altri progetti che seguo, compresi quelli che si sviluppano all’interno degli spazi di Villa Rospigliosi. A questo scopo si è costituita un’associazione di cultura, ChorAsis, che programmaticamente intende valorizzare il lavoro dell’artista, stimolare nel pubblico maggior senso critico attraverso il confronto passato-presente e natura-cultura, temi questi che il complesso architettonico settecentesco di Villa Rospigliosi aiuta ad evidenziare.

P.d’A.: In Toscana e più in generale in Italia esiste una lunga tradizione, direi millenaria, che mette in relazione spazi antichi che accolgono interventi d’arte appartenenti ad epoche differenti. Come ti rapporti a questa tradizione?

R.F.: Hai evidenziato un tema che mi è molto caro. La stratificazione di cui parli è tipica del territorio italiano, le cui città hanno spesso una storia lunga millenni. Il punto è decidere se ignorarla oppure tenerne conto. Per un lungo periodo si è creduto, e forse ancora si crede, che la storia, che pure conforma le nostre città e, in generale, il territorio nazionale, fosse una sorta di gravame del quale liberarsi. Ritengo questo atteggiamento inutilmente presuntuoso, come se della storia avessimo capito proprio tutto. Per l’esperienza che ne ho, è vero esattamente il contrario. Della nostra storia abbiamo, a mio parere, perso memoria per gran parte. Quando un popolo dimentica se stesso direi che è un popolo destinato a diventare colonia di qualcun altro. Il recupero pieno e consapevole del proprio passato mi pare invece che aiuti una lettura più rotonda del mondo. E, soprattutto, invita a considerare che non esiste una sola strada da percorrere e che possiamo considerare variabili interessanti. L’arte e gli artisti, che tendono ad avere una visione non stereotipata, questo modo di operare lo conoscono bene. Quanto vengo facendo da qualche decennio tende a ricordare che il mondo non finisce con la nostra vita ma che lasciamo una eredità che le generazioni seguenti possono leggere e interpretare. Certo è necessaria una visione di ampio respiro. Ed anche una modestia che l’uomo contemporaneo pare aver smarrito. Mi viene a mente, ad esempio, che il paesaggio toscano, così celebrato, è il frutto di generazioni e generazioni di umani, i quali hanno condiviso un progetto e una visione che ha consentito di modificare, nel tempo, un paesaggio altrimenti selvatico e quasi inospitale, meno leggiadro di quello che ci troviamo oggi sotto gli occhi. Il dialogo fra i vari tempi storici, leggibili nelle strade e nelle mura delle nostre città, mi sembra assolutamente stimolante, in grado di produrre risultati sorprendenti, a patto di scavarne i contenuti e riflettere su quanto può davvero essere utile al presente.

P.d’A.: Indaghi queste tematiche anche nel tuo lavoro d’artista?

R.F.: Visto che il rapporto con il tempo e la storia è per me un pensiero costante, direi di si. Cerco di farlo nel modo meno pedante possibile, in modo da creare una attenzione quasi per naturale scivolamento sul tema passato-presente. Questo può avvenire in vario modo: quando il progetto si rivolge esplicitamente ad uno spazio fortemente caratterizzato, con una sua propria storia, cerco di legare la mia individualità a quel luogo. La predisposizione all’ascolto, che coltivo da sempre e che ho acuito nel rapporto costante con il pubblico, grazie anche al contributo metodologico di Munari, mi aiuta molto. Poi ci sono le scelte formali, fatte in piena consapevolezza. So che il pubblico ha, nei riguardi dell’opera d’arte, delle aspettative anche se queste non sono sempre dichiarate. Penso che sia necessario assecondarle, al fine di attivare un rapporto dialogato, evitando così chiusure che impediscono un flusso comunicativo. Questo naturalmente non significa rinunciare al proprio ambito di ricerca ma caso mai perseguire quell’armonizzazione linguistica che consente un sincero rapporto comunicativo. So che molti amici artisti non sono d’accordo, considerando che l’opera d’arte è comunque una espressione linguistica complessa, espressa secondo i modi che l’artista sente pertinenti alla sua ricerca e alla quale il pubblico deve conformarsi. Ci sono però varie questioni da tenere presenti, come ad esempio la stereotipia dello sguardo, la sensibilità individuale e la predisposizione al dialogo che possono essere potenti agenti di bloccaggio della vera comunicazione artistica. In verità bisogna ammettere che l’opera d’arte seleziona gli umani, senza per altro pretendere mai di essere ascoltata. La sua sola presenza è sufficiente. Certo l’artista che la costruisce deve essere all’altezza del compito. Per questo credo si possa dire che gli artisti non sono poi così numerosi come si crede. Il pubblico ha il grande compito di selezionare i più rappresentativi, quelli che esprimono il sentimento comune in un determinato tempo. Per quanto mi riguarda, molto modestamente, mi limito ad appagare un desiderio, rimanendo fedele a quel piacere che provai disegnando, tanto tempo fa, quella racchetta da tennis.

Riccardo Farinelli nato a Firenze nel febbraio 1952, diplomato in discipline pittoriche all’Accademia BB.AA. di Firenze, si considera un ricercatore sia nello specifico artistico che nella sperimentazione di percorsi di incontro con il pubblico. Pittore e grafico ha esposto in gallerie di tutta Italia, preferendo farlo insieme ad amici o in progetti sperimentali ( “Arte di confine”, viale Galilei, 2018); infatti poche sono le personali: Roma galleria La Linea 1980, Milano galleria La linea 1982, Prato Dryphoto 1993, Prato Circoscrizione Nord, 1997, Prato villa Rospigliosi 2019, Pistoia Piano Nobile Home Gallery, 2022. Ha partecipato, unico pittore, al Laboratorio di Progettazione Teatrale di Luca Ronconi, Prato 1976-77. Ha seguito professionalmente in qualità di disegnatore campagne archeologiche Etrusche e Preistoriche della Soprintendenza di Firenze e dell’Università di Siena dal 1972 fino al 1988, anno in cui inizia la collaborazione con il Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci di Prato, del quale sarà responsabile dei progetti d’arte rivolti al pubblico, conclusa nel 2014. Ha contribuito a fondare nel 1975 e nel 1980 “studio 3” e “Magazine”, due Associazioni di ricerca, produzione e organizzazione nel campo delle Arti Visive e, in anni più recenti, “viaggi&scoperte”, associazione di cultura e turismo (2015) e “AA ARTE e ARTE”, associazione di scambio artistico Italia-Cina (2016) per la quale ha curato varie esposizioni nei due Paesi; ha organizzato e curato progetti espositivi monografici, attivando “Arte nei cimiteri”, presso cimitero di Chiesanuova e “progetto ChorAsis”, presso Villa Rospigliosi, ambedue a Prato (2019); mediatore culturale e docente di pittura e storia dell’arte ha insegnato in scuole pubbliche e private, ha pubblicato articoli specialistici e testi scolastici (“ImmaginAzione”, Nuova Italia, 2000); ha organizzato e condotto numerosi corsi, seminari e cicli di conferenze fino ai più recenti “L’arte di comunicare l’arte” (2019-2020), seminario svolto presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Macerata, “Approccio all’immagine: appunti di metodo”, seminario per insegnanti svolto nel 2019 presso spazi ex macelli a Prato, “Modulazione di segni”, corso svolto nel 2022 e nel 2023 presso il liceo musicale Cicognini-Rodari, Prato.

Intervista a Riccardo Farinelli

(Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistacuratore #intervistaartista #curetorinterview #riccardofarinelli

Parola d’Artista: Hi Riccardo, for many artists, childhood coincides with the first manifestation of symptoms of belonging to the art world was it like that for you too? Tell us…

Riccardo Farinelli: Hi, to answer your question properly, I must refer to a childhood memory that is still very vivid in my memory. Hoping not to bore you, I will try to relate it to you. One day my mother, exasperated by having me around while she was preparing the table, put a sheet of squared exercise book and a pencil in front of me and invited me to draw something. I did not know how to proceed and asked what I should draw. My mother replied that I should go around the house and decide which object was most interesting and then proceed to draw it. I decided that the most interesting object for me was a tennis racket hanging on the wall and that was my first drawing that I drew in full consciousness. I was about 5 or 6 years old and as I concentrated on capturing all the details of that object, I realised that I had found a way, as a child who spoke very little, to understand and dialogue with the world by proposing visions that my childish words were unable to express. I understood confusingly but with sure feeling that drawing was my favourite language.

P.d’A.: This first drawing was followed by many others I suppose, did this then lead you to direct your studies in the field of art or did your training move into other territories?

R.F.: Drawing was a constant presence in the years following that discovery, I drew at every opportunity and on whatever piece of paper came my way. When I decided to attend art school and then the Academy of Fine Arts, I learnt to organise myself better: I had, and still have, a drawing pad or notebook and a pencil or marker with me at all times.

During my years at the Academy, I also realised that dialogue with my peers was important to me, the impact that my work as an artist produced in those who looked at it, and the perception that being contemporary meant being the last in a long line of generations, which remained written in our collective memory. This double feeling led me, starting in those very years, to deepen and refine my means of expression, but also to take an interest in what is defined as popularisation and education. At the same time, I sought confirmation and stimulation in the most up-to-date artistic research but also in the non-stereotypical study of the past, which made me a highly appreciated archaeological draughtsman. In fact, I followed Etruscan and prehistoric excavation campaigns directly in the field for about twenty years, an activity that I had to interrupt when I decided to work at the Pecci Centre in Prato.

P.d.A.: I wanted to ask you again about your formative years. Did you first have your artistic ‘First Love’ a work or an artist that further sparked your interest?

Were there any important encounters in your formative years?

R.F.: It is difficult for me to answer this question of yours, in the sense that I cannot isolate a single work or a single artist, in those years everything was coming at me and nothing seemed unimportant. If I had to choose, I would say that my artistic ‘First Love’ was twofold: I was greatly struck by Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Virgin of the Rocks’, for example, whose abysmal fascination I felt, but also by Magritte’s ‘Golconda’, whose alienating procedure introduced me to the mind’s pathways and also to the attention to the linguistic structure of the image, to its deeper meanings. Those two works and their authors helped me a lot. And not only in a professional sense, but also in my mental approach to things in the world. Then yes, some encounters I made have further enriched my artistic feeling, such as the encounter with Vedova, Vespignani, Munari, also helping me to definitively understand how contemporary art does not have, as in the past, a dominant thought, capable of structuring a coherent style that makes it recognisable.

Everything therefore plays on the intensity of feeling and the depth of research. This allows contemporary art to unfold to three hundred and sixty degrees, not infrequently making it difficult to understand. Too much variety can be disconcerting. But this is precisely the point: the choice should not be made on the basis of the style or manner chosen by the artist, but on the empathic capacity that his or her research and sensitivity can have in the visual impact with the public. This information, acquired during those years, has become permanently fixed in my mind, leading me to work equally and naturally in various activities, making my professional categorisation difficult: what am I, a painter, a teacher, a researcher, a cultural worker, an organiser, a curator? I myself find it difficult to answer and have finally stopped asking myself this question.

P.d’A.: Let’s start from this point to explore your work more closely. In your previous answer, you said that you first worked as an archaeological draughtsman, following important excavation campaigns; in this regard, I wanted to ask you why, even today, drawing is preferred to photography in this field?

How was this activity reflected in your later work?

R.F.: Yes, I was working as an archaeological draughtsman in parallel with my work as a painter. I understand that it may seem strange, even anachronistic, that drawing is preferred to photography in archaeology. The fact is that the matter is very practical: photography, its good rendering, is closely related to the weather. If, for example, there is too little light, or too much, the documentary data is distorted and unreliable. Drawing on graph paper, on the other hand, is always reliable, whatever the weather. Furthermore, it is possible to relate the various pieces that emerge from the earth to each other, so as to have a general plan that is always reliable and up-to-date, both horizontally and vertically (i.e. in depth).

The influence of archaeology on my work as a painter and, more generally, in my work as a trainer, disseminator and organiser is not insignificant. I would say that it lies in the motivation that made me approach that world at the time. When I brazenly presented myself to the excavation director the first time, my goal was to be in contact with history. And not in a manner of speaking, but concretely, by extracting traces of the past from beneath the ground that contemporaries tread, to see the depth at which they lie, which is then the plastic rendering of the temporal distance from us.

Observing those objects, seeing them appear in the earth is a very strong emotion that has served me to always remember that the contemporary is nobody’s child, it has its deepest why in the history of the ancestors.

P.d’A.: Was it your way of finding your origins, your motivations?

R.F.: More than my origins, I would say searching for the deepest reasons for the existence of art, particularly in a historical period like the present one that seems to be all about profit, overshadowing, or even denying, everything else. This in my eyes meant the death of art, which not only does not live without a strong collective motivation, but even produces something (the work of art) that in a logic of immediate practicality appears completely useless and useless. It was therefore necessary to recover senses and meanings that had been lost along the way. This was the feeling that guided me. I believe I have remained faithful to that feeling to this day. In my work as a painter, this has meant recovering the full value of drawing, the operational and theoretical basis of the Tuscan school; the use of monochrome, which I have been using for a few years now, enhances this aspect. In my work as a disseminator and curator, that thought has led me to emphasise the relationship of the artistic project with the space that hosts it, highlighting a close dialogue that I find there has always been between the individual personality of the artist and the collectivity within which he or she is immersed. This is a point of view that I see stimulates and interests both the artists and the public that enjoys them.

P.d’A.: In your answer on archaeological drawing, you said that you interrupted this activity to start working for the Education Department at the Pecci Museum. How did you come to this experience and what prompted you to undertake it?

R.F.: At the time, at the end of the 1970s, beginning of the 1980s, I was among those who closely followed the debate in the city on the Pecci Centre, when it did not even physically exist yet. When it finally became a completed structure, I thought it would be nice to combine my closeness to contemporary art with the pleasure of making its rules and contents known, allowing me to stand on the threshold between those two worlds. So I entered the competition that was announced for the Education Department. I came first in the ranking list and was hired. This marked the beginning of a very interesting period for me, where I had the time to study the work of the artists who were gradually appearing in the halls and, at the same time, to study ways of conveying the content of their work to the public. The three-year meeting with Bruno Munari, who periodically supervised the work in the workshop, was priceless. Thanks to him, I definitely understood the need for rigour in work, proposed with kindness. A positive version of the saying ‘iron fist in velvet gloves’. My hidden design was to create, over time, an audience for art, such that its fruition and enjoyment could be extended to a larger number of people, so as to help it emerge from asphyxiation due to lack of oxygen. A danger that in my opinion is still very much present today. I had not foreseen that that kind of work would be so demanding that it would prevent me from other activities that I also loved.

P.d’A.: Yes, it’s true that teaching engulfs everything and completely drains your batteries. How long did your activity at Pecci go on for and which aspects did you deal with in the Education Department?

R.F.: My activity at the Pecci Centre went on for twenty-six years. Particularly in the last few years, I was responsible for projects related to activities aimed at the public. This meant reviewing, rewriting, and redesigning everything (lectures, guided tours, workshops) with every change of works in the exhibition halls. Then there was the activity of courses and conferences on approach methodology, which was requested by other cultural and educational institutions (museums, associations, academies of fine arts, school managements, etc.); finally, there was the work of documenting and systematising the work done, which was useful for redesigning activities. I was also the coordinator of the Culture Department, which brought together the Education Department and the specialised library within the Centre, at that time the only one in Italy of that size.

P.d’A.: And did your work as an artist during these years continue or did you have to put it aside?

R.F.: I cannot think of myself without drawing and painting, so I have continued to do so. Certainly my public presence as an artist was less assiduous in those years, definitely slowed down. However, thanks to the constant work at the Centro Pecci, the proximity to high-profile contemporary art, and the study of authors, my work as an artist was consolidated, finding new stimuli for reflection on the formal choices made at the time, which I have never denied. Then frequent contact with the public allowed me to better understand their attitudes towards art, to notice nuances that allowed me to refine my technical tools and attempt non-trivial ways of approaching it, not only in the visual sense.

P.d.A.: Is your curatorial activity in some way a child of your teaching/dissemination experience?

R.F.: In some ways yes, in the sense that curatorial activity is part of a more overall design that, in my mind at least, reconstructs (or tries to reconstruct) the positive triangulation between artist-work-public. A question that has occupied my mind since my beginnings in the art world. Indeed, it was not difficult to realise from the very first exhibitions I did that the art world is made up of many stereotypes and few people. I always thought that this did not help but burdened the work of artists. Contemporary art, ever since the avant-garde, has worked hard to remove stereotypes from the public’s judgement, but it does not seem to have had great results. What is more, the hoped-for broadening of fruition has not taken place or, when it has, it has taken the monstrous form of mass tourism, which literally consumes without understanding. I thought I had to try, in my own small way, to take the artist and his work out of the siege, to make him feel less alone in his quest. I tried, as Klein would say, to highlight the need for sharing and empathy in approaching artists’ work. These concepts have always underpinned my work as a curator, which in recent years I have brought into physical reality by organising exhibitions in non-deprived but significant and strongly characterised venues, which artists are invited to interpret. Examples of this are the exhibitions curated at the 18th-century Villa Rospigliosi in Prato, but also those I have called ‘Borderline Art’ and ‘Art in Cemeteries’, two exhibition projects where the location is decidedly unconventional but capable, I believe, of stimulating questions and comparisons. And this is the criterion that has always guided my activity as an educator and disseminator as well: to accompany the citizen/spectator to discover the living substance of the work of art and not to passively list a series of information.

P.d’A.: The three projects you describe above also involve you as an artist, how do you reconcile the two sides of your activity?

R.F.: When I think of a new exhibition project, I imagine it first and foremost for myself, as a stimulus to my curiosity, in an attempt at an unencumbered dialogue. This is also why those projects I mentioned have such unusual scenarios. The works I produce for that particular project are in some way an attempt to respond. I am among those who believe that the artist alone is not enough. Then it occurs to me that it might also be stimulating for some of the artists I happen to know, so I propose it to them and, if they believe, they accept and we discuss it. Finally, it comes quite naturally to me to think of writing something that might help them understand their choices. I always imagine the artist’s work as a non-definitive contribution around a question mark or a suggestion. After all, my real obsession remains the audience. Without it, art would be nothing. Indeed, I would add that not only are people, each and every individual, indispensable to art but also represent its ever-renewed stimulus to produce works. The centrality of the public was well understood by Duchamp, who had clear words to say on this subject. He too had rightly fought against the stereotyped gaze, having understood its power to block any flow of information from the work to the viewer. I think I agree with him and share those ideas of his.

P.d’A.: In your work, how important is the dialogue with places?

R.F.: It has a lot, and for many reasons. The first of these is having understood that a place, an environment is not neutral, it emanates its own narrative and I think an artist must bear this in mind. We are perhaps too used to thinking of the work in the space of a gallery, which often tries to be as neutral as possible, to fully consider this aspect. Instead, the environment, the place positively conditions the artist’s work, almost to the point of establishing the size of the work, its format, the medium to be used. Then it is also valid as a metaphor for the necessary and indispensable dialogue that the work has with human beings, of the present as well as the past. The work of art is not a closed world, impermeable to the world.

P.d’A.: What relationship exists between your work as an artist and the categories of time and space?

R.F.: It depends from what point of view you understand it. From what we can define as operational, I understand time as a continuous dialogue between what is my personal memory (individual time) and what is diluted in history (collective time). An encounter that is always fruitful and never exhausting, which stimulates me to continue to give non-stereotypical meaning to established formal modes. This means not too hastily dismissing what comes from the past but trying to reconsider it in the light of the present. This is what happens to me with drawing for example, of which I perceive the possibility of an important synthesis between history and contemporary sensibility. Working in monochrome was the logical consequence. Still from an operational point of view, I see space as limited to the format I choose. I know that I can, if I want, fit as much space into it as I want. This is the advantage of working in the realm of representation, a universe of which image artists should be well aware.

P.d’A.: When you work with other artists, what are the criteria you use to identify whom to involve?

R.F.: The first criterion is the work, i.e. what I already know about a particular artist. This helps me a lot in my choice, which is also conditioned by compatibility with the project I have in mind. In fact, I try to involve artists whose work enhances the project, which is often designed primarily for a wide audience, but also their own way of being artists, presenting unusual aspects to the public. This would not be the case if the choice were random, dictated perhaps only by sympathy and esteem. For example, all the artists I invited for the “Art in the Cemeteries” project, which presupposed a site-specific work, I sincerely thought that they would each make a stimulating contribution to the meanings of that project, which was intended to bring the world of the dead into dialogue with that of the living, that is, to attempt to remove the collective estrangement from the feeling of lack and the end of life, a modality so present in the contemporary world. Not an easy intention to interpret, considering that the venue was a space inside the Chiesanuova cemetery in Prato. I was able to see, even on that occasion, that both the presentation of arguments outside the norm and the departure from the usual places, the so called designated places, is stimulating for the audience but also for the artists.

P.d.A.: One of your projects involves an intervention by artists along a street of intense car transit. This project, in addition to the non-purposeful location, imposes an extremely limited time of use, a few fractions of a second. Do you think that those who find themselves passing by such interventions, without knowing anything about them, are really able to realise that what they have in front of them at that moment is a work of art?

R.F.: I would say that that project, which is still in the works even though it has been in existence for almost five years, bets on several levels: the direct confrontation with the advertising image, from which it “steals” space, and, indeed, the time of fruition. If, despite everything, my series of three gonfalons manages to stimulate a reflection, a thought, I feel satisfied. After all, this is what distinguishes a work of art from an advertising image: being able to trigger an active and critical mental process, capable of activating questions and reflections, while the other has the sole objective of convincing one to buy. If those who benefit from it at the moment do not realise the change of register, they have benefited from it anyway and it will pay off. The important thing is to persevere, as I believe it takes a lot of time and a continuous and constant strategy to be able to come up with some results. Of course, such a project also forces the artist to reorganise his means of expression, to make them more suitable for a very fast urban use. The choice of the right artist is clearly very important. It is so in the case of ‘border art’ but also for all the other projects I follow, including those that take place within the Villa Rospigliosi spaces. To this end, a cultural association, ChorAsis, has been set up, which programmatically intends to enhance the work of the artist, to stimulate a greater critical sense in the public through the comparison between past-present and nature-culture, themes that the 18th century architectural complex of Villa Rospigliosi helps to highlight.

P.d’A.: In Tuscany, and more generally in Italy, there is a long tradition, I would say a thousand years old, that relates ancient spaces that host art interventions belonging to different eras. How do you relate to this tradition?

R.F.: You have highlighted a theme that is very dear to me. The stratification you speak of is typical of the Italian territory, whose cities often have a history that is thousands of years long. The question is whether to ignore it or take it into account. For a long time it was believed, and perhaps still is believed, that history, which also shapes our cities and, in general, the national territory, was a sort of burden to be rid of. I consider this attitude unnecessarily presumptuous, as if we had understood everything about history. In my experience, exactly the opposite is true. We have, in my opinion, largely lost memory of our history. When a people forgets itself, I would say that it is a people destined to become someone else’s colony. Instead, the full and conscious recovery of one’s past seems to me to help a more rounded reading of the world. And, above all, it invites us to consider that there is not just one way to go and that we can consider interesting variables. Art and artists, who tend to have a non-stereotypical vision, know this well. What I have been doing for a few decades tends to remind us that the world does not end with our lives but that we leave a legacy that subsequent generations can read and interpret. Certainly a broad vision is needed. And also a modesty that contemporary man seems to have lost. It occurs to me, for example, that the Tuscan landscape, so celebrated, is the fruit of generations and generations of humans, who shared a project and a vision that allowed for the modification, over time, of an otherwise wild and almost inhospitable landscape, less graceful than the one we find before our eyes today. The dialogue between the various historical times, legible in the streets and walls of our cities, seems to me to be absolutely stimulating, capable of producing surprising results, provided we dig into its contents and reflect on what can really be useful to the present.

P.d.A.: Do you also investigate these issues in your work as an artist?

R.F.: Since the relationship with time and history is a constant thought for me, I would say yes. I try to do this in the least pedantic way possible, so as to create a focus almost by natural slippage on the past-present theme. This can happen in various ways: when the project explicitly addresses a strongly characterised space, with its own history, I try to link my individuality to that place. The predisposition to listen, which I have always cultivated and which I have sharpened in my constant relationship with the public, thanks also to Munari’s methodological contribution, helps me a lot. Then there are the formal choices, made in full awareness. I know that the public has expectations of a work of art, even if these are not always declared. I think it is necessary to indulge them, in order to activate a dialogical relationship, thus avoiding closures that prevent a communicative flow. This of course does not mean renouncing one’s own sphere of research, but in any case pursuing that linguistic harmonisation that enables a sincere communicative relationship. I know that many artist friends do not agree, considering that a work of art is in any case a complex linguistic expression, expressed in ways that the artist feels are pertinent to his or her research and to which the public must conform. There are, however, various issues to keep in mind, such as stereotypical gaze, individual sensitivity and predisposition to dialogue that can be powerful blocking agents of true artistic communication. In truth, it must be admitted that the work of art selects humans, without ever claiming to be heard. Its mere presence is sufficient. Certainly the artist who constructs it must be up to the task. This is why I think it can be said that artists are not as numerous as people think. The public has the great task of selecting the most representative, those who express the common feeling at a given time. As for me, very modestly, I am merely fulfilling a desire, remaining faithful to that pleasure I felt when I drew that tennis racket so long ago.

Riccardo Farinelli, born in Florence in February 1952, graduated in painting disciplines at the Accademia BB.AA. in Florence, considers himself a researcher both in the specific artistic field and in the experimentation of paths of encounter with the public. As a painter and graphic artist, he has exhibited in galleries all over Italy, preferring to do so together with friends or in experimental projects (“Arte di confine”, viale Galilei, 2018); in fact, there are only a few personal exhibitions: Rome galleria La Linea 1980, Milan galleria La linea 1982, Prato Dryphoto 1993, Prato Circoscrizione Nord, 1997, Prato villa Rospigliosi 2019, Pistoia Piano Nobile Home Gallery, 2022. He participated, the only painter, in Luca Ronconi’s Theatre Design Workshop, Prato 1976-77. He followed professionally as a draughtsman Etruscan and Prehistoric archaeological campaigns of the Soprintendenza di Firenze and the University of Siena from 1972 until 1988, the year in which he began his collaboration with the Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato, for which he was responsible for art projects aimed at the public, which ended in 2014. In 1975 and 1980 he helped found ‘studio 3’ and ‘Magazine’, two research, production and organisation associations in the field of Visual Arts and, in more recent years, ‘viaggi&scoperte’, a culture and tourism association (2015) and ‘AA ARTE e ARTE’, artistic exchange association Italy-China (2016) for which he has curated various exhibitions in the two countries; he has organised and curated monographic exhibition projects, activating ‘Art in the Cemeteries’, at the Chiesanuova cemetery and ‘Project ChorAsis’, at Villa Rospigliosi, both in Prato (2019); a cultural mediator and teacher of painting and art history, he has taught in public and public schools, published specialist articles and scholarly texts (“ImmaginAzione”, Nuova Italia, 2000); he has organised and conducted numerous courses, seminars and cycles of lectures up to the most recent “L’arte di comunicare l’arte” (2019-2020), a seminar held at the Academy of Fine Arts in Macerata, “Approccio all’immagine: appunti di metodo”, a seminar for teachers held in 2019 at the ex-slaughterhouse spaces in Prato, “Modulazione di segni”, a course held in 2022 and 2023 at the Cicognini-Rodari music high school, Prato.

ENIGMA installazione 2020

Arte nei cimiteri

es.laboratorio libro delle stelle 2012

es.laboratorio ragazzino che cammina 2010

Oro su nero, 2021

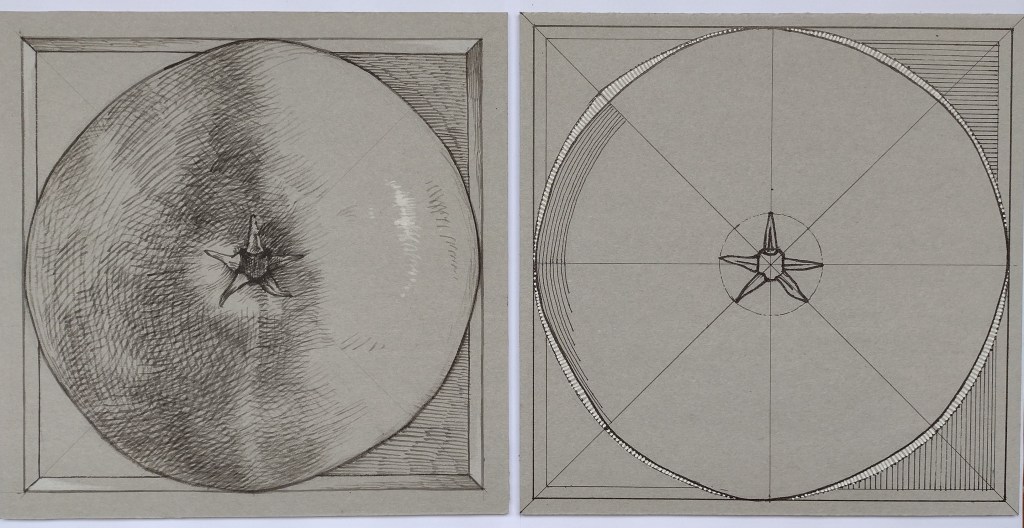

progetto 20×20 Natural forms la pera non è un cerchio 2023