(▼Scorri verso il basso per la versione Italiana)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #mollythomson

Parola d’Artista:For most artists, childhood represents the golden age when the first. Symptoms of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell me.

Molly Thomson: Having parents who were both art teachers meant that I grew up in an atmosphere where drawing, painting and making things felt pretty normal – though even with that degree of familiarity, the art world seemed a very far-away thing. However, despite other areas of interest, it was clear in the end that I was heading in that direction.

P.d’A.: What studies have you done?

M. T.: For my undergraduate degree I studied sculpture and history of art on a combined course at Edinburgh University and College of Art. Choosing to specialise in sculpture was not what I had originally expected to do, but the sideways step from painting felt liberating and it was good not to be relying on the superficial skills I had brought with me to college. There was something about the resistance of different materials that I responded to. Having said this, my work gradually began to incorporate aspects of painterly language and when I was ready for post-graduate study it was the Painting school at the Royal College of Art that I went to.

P.d’A.: Were there any important encounters in your formative years?

M. T.: Rather than any particular individual encounters I would say that the formative things have been the problems encountered, challenges met (or at least not run away from), interesting fellow-travellers, the books read, exhibitions seen – and life experiences themselves. The formative process goes on. I hope so, at least!

P.d’A.: How was the idea of space born, and how does it develop in your work?

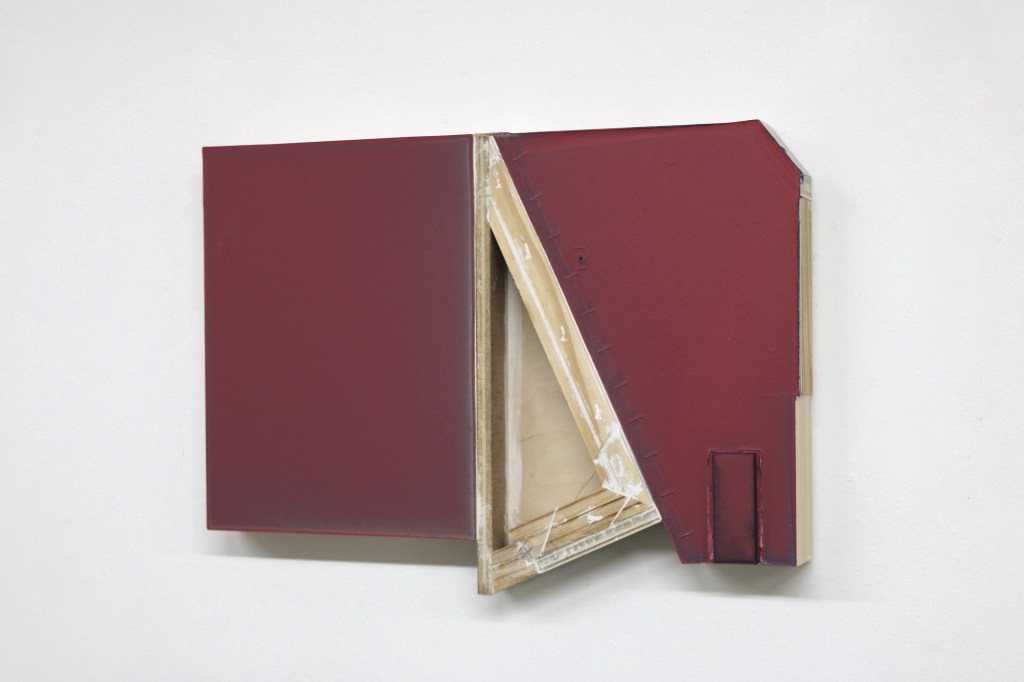

M. T.: Thoughts about space were there in my early days as a sculpture student. In applying colour to objects or to panels with protruding elements I became interested in the possibilities of both real and illusionistic space operating together. Despite various detours and meanderings along the way these concerns are still present. I am interested in the physical presence of painting, whether a piece of work inhabits the wall or descends to the floor or other surface. In recent years I have been thinking about the normally-not-to-be-seen space behind the painting’s facade. Cut-outs or displaced sections can bring the interior space of a panel into play. The painting-object has volume. It casts shadows and has shadows within.

P.d’A.: What role does colour play in what you do?

M. T.: I don’t pre-plan what happens with colour and first decisions are often made through a relationship with, or reaction against, other work on the go. Subsequent layers on a work are a response to what already exists – to the developing feel of the piece. Quiet/upbeat/sombre etc. Sometimes, though, it is necessary to provide the visual jolt of something very different (colour I might rarely use) in order to prompt a new quality, even if this is only in the early stages. While working with thin layers can allow colours a quiet interaction with one another, the edges often reveal the history in a more pronounced way.

P.d’A.: How important is geometry in your work?

M. T.: Although the way that I interact with the initial rectangle as well as the relative simplicity of the final structure might suggest geometry this is more the result of a series of limited moves than a primary concern. Found materials apart, I invariably start with the constraint of that basic, bare panel. It makes the simplest of demands; that I displace its symmetry (its ‘geometry’) in some way. This is done through cuts, excisions, insertions and reversals. I need the work to flex its elbows, to ‘fight back’ and to be provoked into recomposing itself. Architectural structures might sometimes be evoked, but in a way that grows out of the rectilinear structure of the painting’s body. Verticals, horizontals and new-cut angles must hold together, and although sometimes I go too far and they threaten to fall apart, in the end there is a concern with establishing some kind of poise or order, albeit one with glitches or traces of change.

P.d’A.: Are you interested in the painterly qualities?

M. T.: I am very interested in the painterly qualities, even though in my work these can appear to be delicate and quite finely-tuned. Mostly, I apply acrylic paint through pouring, which gives me a sense of ‘remove’ from the process and allows me almost to be a spectator to what takes place. While of course I have choice about colour and thickness or thinness of the paint, there is no formula and I can never exactly predict the results. I welcome this degree of uncertainty as a necessary counter-balance to the urge to control. Sometimes I will have aimed to achieve an opaque, skin-like quality with the paint, while at other times it is the paint’s capacity for something more porous or semi-transparent that I am thinking about. At this point, having done the pour, I just have to wait and watch. With work that has hung around the studio for many months and been returned to again and again I will sometimes knock it back with a sander. This will expose mendings and previous strata of paint, resulting in a very different kind of surface. Sometimes this is all that is needed, sometimes it is a new start.

P.d’A.: Do you work on several pieces together?

M. T.: I always have multiple pieces on the go at the same time. This is partly practical, as poured paint takes a while to dry, and partly a strategy for keeping a light touch and not trying to force outcomes. I like having unresolved things in the corner of my eye and it can be useful to bring something back into play alongside new pieces. On the other hand, too much visual noise can sometimes be a problem, so I have phases of clearing the decks and making space for just a few key players.

P.d’A.: How important is light in what you do?

M. T.: The physical light in which a work sits can be very important, though it’s hard always to be completely in control of this. Work – especially pieces with three-dimensional elements – can seem different when the direction of light changes, so this is an important consideration in exhibiting. (There is, of course, the question of internal, illusionistic light, which might be hinted at by the paint itself. And there is, by contrast, the absence of light in a dark interior).

P.d’A.: Does your daily practice of art lead you towards a spiritual path?

M. T.: I don’t think of it in these terms, though the repetitive routine of practice focuses the mind and creates a space for reflective thought.

P.d’A.: How do your works relate to the space in which you install them?

M. T.: I am interested in the relationship the work has with the space it inhabits whether, initially, the studio or eventually the showing space – though control of the latter is not always fully in my hands. Effectively, the space is an extension of the piece, however small that individual work might be, or however expansive or confined the space is. I am interested in the way the space might frame work(s), presenting corners and edges, gaps and frames, as well as providing echoes or counterpoints that affect way the work operates. Invariably the work has to be seen entirely afresh in the context of a new environment.

P.d’A.: What importance do the categories of time and space have in what you do?

M. T.: I’m not quite sure how to answer this question. As far as time is concerned, there is the time/duration of making, the time involved by the observer in looking – and possibly a less linear sense of time that exists in experiencing the work itself – perhaps to do with memory and imagination. No doubt they are all important and, along with questions concerning space, completely interlinked.

Molly Thomson was born in Scotland. She studied sculpture at Edinburgh College of Art and art history at Edinburgh University. This was followed by an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art in London. After her studies she combined painting with teaching, most recently at Norwich University of the Arts. She currently works full-time in her studio near Norwich. She is represented by &Gallery in Edinburgh.

Recent exhibitions include: Image_Object, Poimena Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania (2020), Vitalistic Fantasies, Contemporary British Painting, The Cello Factory, London (2020), Orbit, Poimena Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania (2021), Que des Femmes, 6th Biennial of Non-Objective Art, Pont de Claix, France (2021), Art Matters 4, online show, Galerie Biesenbach, Cologne (2021), Line, Colour, Form, & Gallery, Edinburgh (2022), An Expanding Field, Gloam, Sheffield, UK (2022), At Cross Purposes, Elysium, Swansea, Wales (2023), Trialogue, 3-person show, Galerie Biesenbach, Cologne (2023), Realignment, solo show, & Gallery, Edinburgh (2023), Molly Thomson and Franziska Reinbothe, Raumx, London (2023)

Versione Italiana

Intervista a Molly Thomson

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #mollythomson

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui si manifestano i primi. Cominciano a manifestarsi i sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per lei? Mi dica.

Molly Thomson: Avendo genitori che erano entrambi insegnanti d’arte, sono cresciuta in un’atmosfera in cui disegnare, dipingere e fare cose mi sembrava abbastanza normale, anche se, pur con questo grado di familiarità, il mondo dell’arte sembrava una cosa molto lontana. Tuttavia, nonostante le altre aree di interesse, alla fine era chiaro che stavo andando in quella direzione.

P.d’A.: Quali studi ha fatto?

M. T.: Per la mia laurea ho studiato scultura e storia dell’arte in un corso combinato presso l’Università e il College of Art di Edimburgo. Scegliere di specializzarmi in scultura non era quello che mi aspettavo di fare, ma il passo indietro rispetto alla pittura mi è sembrato liberatorio ed è stato bello non fare affidamento sulle competenze superficiali che avevo portato con me all’università. C’era qualcosa nella resistenza dei diversi materiali che mi piaceva. Detto questo, il mio lavoro ha cominciato gradualmente a incorporare aspetti del linguaggio pittorico e quando sono stata pronta per gli studi post-laurea ho frequentato la Scuola di pittura del Royal College of Art.

P.d’A.: Ci sono stati incontri importanti negli anni della sua formazione?

M. T.: Più che gli incontri individuali, direi che le cose formative sono state i problemi incontrati, le sfide affrontate (o almeno da cui non si è scappati), i compagni di viaggio interessanti, i libri letti, le mostre viste – e le stesse esperienze di vita. Il processo formativo continua. Almeno lo spero!

P.d’A.: Come è nata l’idea dello spazio e come si sviluppa nel suo lavoro?

M. T.: Le riflessioni sullo spazio erano già presenti nei primi tempi in cui studiavo scultura. Applicando il colore a oggetti o a pannelli con elementi sporgenti, mi sono interessata alle possibilità dello spazio reale e di quello illusorio. Nonostante le varie deviazioni e i meandri del mio percorso, queste preoccupazioni sono ancora presenti. Mi interessa la presenza fisica della pittura, sia che un’opera abiti la parete sia che scenda sul pavimento o su altre superfici. Negli ultimi anni ho pensato allo spazio normalmente non visibile dietro la facciata del dipinto. Ritagli o sezioni spostate possono mettere in gioco lo spazio interno di un pannello. L’oggetto-pittura ha un volume. Produce ombre e ha ombre all’interno.

P.d’A.: Che ruolo ha il colore nel suo lavoro?

M. T.: Non pianifico in anticipo ciò che accade con il colore e le prime decisioni sono spesso prese in base a una relazione o reazione con altri lavori in corso. Gli strati successivi di un’opera sono una risposta a ciò che già esiste, alla sensazione di sviluppo del pezzo. Tranquillità/superficie/sombrello ecc. A volte, però, è necessario fornire la scossa visiva di qualcosa di molto diverso (un colore che potrei usare raramente) per sollecitare una nuova qualità, anche se questo avviene solo nelle fasi iniziali. Mentre lavorare con strati sottili può permettere ai colori di interagire tranquillamente tra loro, i bordi spesso rivelano la storia in modo più marcato.

P.d’A.: Quanto è importante la geometria nel suo lavoro?

M. T.: Anche se il modo in cui interagisco con il rettangolo iniziale e la relativa semplicità della struttura finale potrebbero far pensare alla geometria, questa è più il risultato di una serie di mosse limitate che una preoccupazione primaria. A parte i materiali trovati, inizio invariabilmente con il vincolo di quel pannello di base, nudo. La richiesta è la più semplice: spostare la sua simmetria (la sua “geometria”) in qualche modo. Questo avviene attraverso tagli, esclusioni, inserimenti e inversioni. Ho bisogno che l’opera fletta i gomiti, che “reagisca” e che sia provocata a ricomporsi. A volte si possono evocare strutture architettoniche, ma in un modo che si sviluppa dalla struttura rettilinea del corpo del dipinto. Verticali, orizzontali e nuovi angoli di taglio devono stare insieme, e anche se a volte esagero e minacciano di andare in pezzi, alla fine c’è la preoccupazione di stabilire una sorta di equilibrio o di ordine, anche se con difetti o tracce di cambiamento.

P.d’A.: Le interessano le qualità pittoriche?

M. T.: Mi interessano molto le qualità pittoriche, anche se nel mio lavoro possono apparire delicate e molto raffinate. Per lo più applico i colori acrilici per colata, il che mi dà un senso di “rimozione” dal processo e mi permette di essere quasi uno spettatore di ciò che avviene. Sebbene abbia la possibilità di scegliere il colore e lo spessore o la diluizione della pittura, non esiste una formula e non posso mai prevedere con esattezza i risultati. Accolgo questo grado di incertezza come un necessario contrappeso all’impulso di controllo. A volte ho puntato a ottenere una qualità opaca, simile alla pelle, mentre altre volte ho pensato alla capacità della vernice di essere più porosa o semitrasparente. A questo punto, dopo aver effettuato il versamento, non mi resta che aspettare e osservare.

Nel caso di lavori che sono rimasti in studio per molti mesi e che sono stati ripresi più volte, a volte li riporto indietro con una levigatrice. In questo modo si espongono i rammendi e i precedenti strati di pittura, ottenendo un tipo di superficie molto diverso. A volte questo è tutto ciò che serve, altre volte è un nuovo inizio.

P.d’A.: Lavorate su più opere insieme?

M. T.: Ho sempre più opere in corso contemporaneamente. In parte è una questione pratica, perché la vernice versata impiega un po’ di tempo ad asciugarsi, e in parte è una strategia per mantenere un tocco leggero e non cercare di forzare i risultati. Mi piace avere cose irrisolte con la coda dell’occhio e può essere utile rimettere in gioco qualcosa insieme a nuovi pezzi. D’altra parte, un eccesso di rumore visivo a volte può essere un problema, quindi ho delle fasi in cui sgombro il campo e faccio spazio solo a pochi protagonisti.

P.d’A.: Quanto è importante la luce nel suo lavoro?

M. T.: La luce fisica in cui si trova un’opera può essere molto importante, anche se è difficile avere sempre il pieno controllo su questo aspetto. I lavori, soprattutto quelli con elementi tridimensionali, possono sembrare diversi quando cambia la direzione della luce, quindi è una considerazione importante quando si espone. (Naturalmente c’è anche la questione della luce interna, illusionistica, che potrebbe essere accennata dalla pittura stessa. E c’è, per contrasto, l’assenza di luce in un interno buio).

P.d’A.: La sua pratica artistica quotidiana la porta verso un percorso spirituale?

M. T.: Mi interessa la relazione che l’opera ha con lo spazio che abita, sia esso inizialmente lo studio o eventualmente lo spazio espositivo, anche se il controllo di quest’ultimo non è sempre completamente nelle mie mani. In effetti, lo spazio è un’estensione dell’opera, per quanto piccola possa essere la singola opera, o per quanto ampio o ristretto sia lo spazio. Mi interessa il modo in cui lo spazio può incorniciare le opere, presentando angoli e bordi, spazi vuoti e cornici, oltre a fornire echi o contrappunti che influenzano il modo in cui l’opera opera opera. Invariabilmente l’opera deve essere vista completamente nuova nel contesto di un nuovo ambiente.

P.d’A.: Che importanza hanno le categorie di tempo e spazio nel suo lavoro?

M. T.: Non so bene come rispondere a questa domanda. Per quanto riguarda il tempo, c’è il tempo/durata della realizzazione, il tempo che l’osservatore impiega per guardare, e forse un senso meno lineare del tempo che esiste nell’esperienza dell’opera stessa, forse legato alla memoria e all’immaginazione. Senza dubbio sono tutti importanti e, insieme alle questioni relative allo spazio, completamente interconnessi.

Molly Thomson è nata in Scozia. Ha studiato scultura all’Edinburgh College of Art e storia dell’arte all’Università di Edimburgo. Ha poi conseguito un master in pittura presso il Royal College of Art di Londra. Dopo gli studi ha affiancato alla pittura l’insegnamento, da ultimo presso la Norwich University of the Arts. Attualmente lavora a tempo pieno nel suo studio vicino a Norwich. È rappresentata dalla &Gallery di Edimburgo.

Tra le mostre recenti ricordiamo: Image_Object, Poimena Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania (2020), Vitalistic Fantasies, Contemporary British Painting, The Cello Factory, Londra (2020), Orbit, Poimena Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania (2021), Que des Femmes, 6th Biennial of Non-Objective Art, Pont de Claix, Francia (2021), Art Matters 4, mostra online, Galerie Biesenbach, Colonia (2021), Line, Colour, Form, & Gallery, Edimburgo (2022), An Expanding Field, Gloam, Sheffield, Regno Unito (2022), At Cross Purposes, Elysium, Swansea, Galles (2023), Trialogue, mostra di tre persone, Galerie Biesenbach, Colonia (2023), Realignment, mostra personale, & Gallery, Edimburgo (2023), Molly Thomson and Franziska Reinbothe, Raumx, Londra (2023)

Flex Acrylic on panel construction, 56.5x38x5cm, 2023