Edito da La vita felice, nella collana Echi. www.lavitafelice.it

(▼Scroll down for English text)

#paroladartista #intervistartista #intervistacritico #elenaelasmar #pietrogagliano #ceraunavoltaederaceleste #lavitafelice #echi

Parola d’Artista: Visto che Pietro nella sua consolazione che introduce questo tuo libro ha citato un passo della Genesi vorrei anche io partire da lì:” In principio era il verbo…” è scritto ma in questo caso mi sembra che sia più appropriato dire In principio era l’immagine visto che il libro si apre con una sequenza di riproduzioni di tuoi lavori su carta. Come nasce questo libro e perché?

Elena El Asmar: L’idea di fare questo libro è nata con Pietro Gaglianò, in estate, a bordo piscina, o forse prima, magari mentre eravamo entrambi a guardare le nuvole di uno stesso cielo seppure in regioni geograficamente diverse.

Pietro conosceva bene il lavoro sugli acquerelli perché ne avevo esposti alcuni anni fa in una mostra, da lui curata, a Venezia e, allo stesso tempo, aveva avuto modo di leggere i testi che compongono il libro.

Così, in uno dei nostri molti discorsi, abbiamo iniziato a ipotizzare come sarebbe stato trasformare in un’esperienza narrativa, che è quella propria dei libri, le immagini e le parole.

Ho iniziato così a muovere immagini e parole sulla carta, principalmente secondo necessità formali.

La messa in opera di una prima bozza del libro è coincisa con una visita nello studio di Gerardo Mastrullo e Ginevra Quadrio Curzio della casa editrice La Vita Felice, venuti per confrontarsi, con me e Luca Pancrazzi, di un nuovo progetto che volevano avviare ovvero iniziare una collaborazione con alcuni artisti e artiste, per la creazione del loro stand nelle varie fiere dei libri presentando di volta in volta una pubblicazione che riguardasse l’artista coinvolto.

Il menabò che avevo appoggiato sul tavolo ha catturato la loro attenzione e il loro interesse e così è stato inaugurato, oltre al progetto “Stanze d’Artista” in occasione della fiera di Roma “Più libri più liberi” 2023, anche una nuova collana della casa editrice dal nome “Echi”.

P.d’A.: Dal principio questo libro ci fa viaggiare e coltivare la dimensione della rêverie invitando il lettore a guardare attraverso un caleidoscopio di immagini, colori, profumi e sapori che generano un luogo avvolgente, sensuale di grande fascino. Che importanza ha la relazione con Gaston Bachelard?

Pietro Gaglianò: Lo spazio della rêverie, come luogo delle connessioni inattese, dell’invenzione che procede per aperture e non per costruzioni, per libere associazioni che fanno a meno dei condizionamenti della tradizione occidentale, tutto questo è, in realtà, presente nel lavoro di Elena già da molti anni. Le opere raccolte in questo libro sono forse quelle in cui questo legame è più evidente, anche per lo slittamento continuo tra i due medium: dalla parola all’immagine e, circolarmente, dall’immagine alla parola. Bachelard (assieme a altri pensatori anche remoti dal dibattito sulla fenomenologia dell’arte) è sicuramente un riferimento importante per la sua poetica, ma la sua interpretazione è sempre eretica, è sempre un “far proprio”, indifferente alla purezza filologica, alla coerenza dello studio.

P.d’A.: In questo libro mi sembra abbia una sua importanza l’idea di tempo, tal volta dichiarata apertamente altre volte più sotto traccia ma sempre presente. Ci sono poi vari aspetti che allo stesso modo ritornano come i fili di un ordito che intrecciandosi fra loro disegnano un vasto paesaggio, che come un puzzle si compone di molteplici frammenti/tessere. Ti volevo chiedere che importanza ha avuto l’idea di fare ordine nella costruzione della struttura con cui hai concatenato le poesie e le immagini che compongono questo libro?

E.E.A.: La struttura e la successione delle immagini, prima, e dei testi, poi, suggerisce un determinato percorso che io ho immaginato potesse compiere lo sguardo nello sfogliare e leggere il libro.

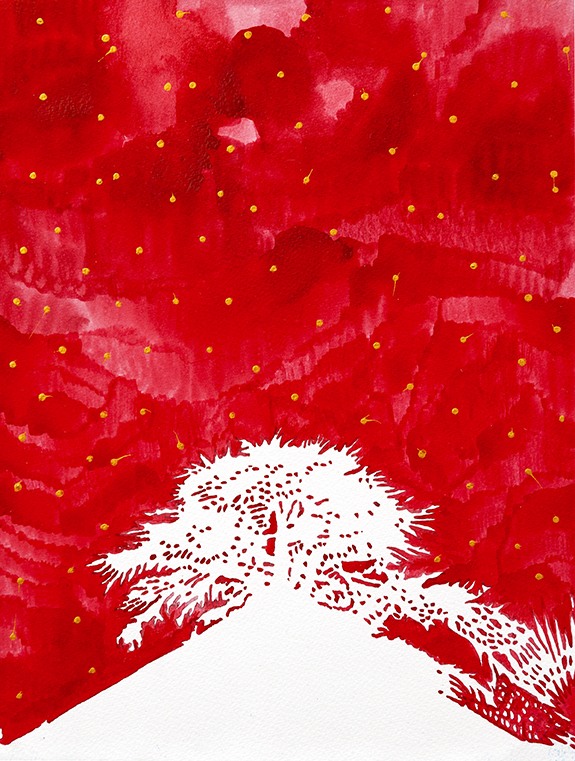

Gli acquerelli hanno tutti come riferimento dei luoghi precisi che ho frequentato negli ultimi anni e che compongono una sorta di mio ritratto autobiografico fatto per immagini.

Anche i testi risentono di questa necessità di raccontarmi attraverso le immagini dove colori e segni divengono parole, pause, spaziature.

Infine, in una dimensione più sentimentale che logica, le parole e le immagini si legano a loro discrezione, e a discrezione di chi guarda, come fossero una cassa di risonanza le une per le altre.

P.d’A.: La poesia ti accompagna da tempo o è una scoperta recente?

E.E.A.: Tutte le volte che accendo una sigaretta.

P.d’A.: Sei una lettrice di poesia, che poeti leggi?

E.E.A.: Stamani, piangendo, come Dino Campana ho giurato fede all’azzurro, poi ho visto gli uccelli e la neve di Emily Dickinson e ho fatto colazione con focacce d’uva passa e con mele perché anch’io sono malata d’amore come Salomone nel Cantico dei Cantici. Saranno ancora molte le visite, oggi, da qui a sera.

P.d’A.: Pietro, leggendo la tua consolazione mi è tornato in mente un ricordo di una affermazione di Ettore Spalletti: La bellezza è come una lama taglia come una bella donna che attraversa una piazza. Perché è necessario secondo te continuare ad interrogarsi sulla natura della bellezza?

P.G.: La bellezza in ogni discorso sull’arte è sempre una metafora di qualcos’altro. In un certo senso potremmo dire che la bellezza è essa stessa l’arte, se è buona arte: è il veicolo per un’esperienza estetica o cognitiva di dissenso. Intendo dire che l’arte (o la bellezza) permette di riconoscere qualcosa del mondo che il mondo (la grigia amministrazione del mondo) non intende mostrare o non è capace di mostrare. Chi fa autentica esperienza della bellezza (o dell’arte) cambia il proprio pensiero, anche solo in minima parte, e attiva forme di resistenza, di antagonismo rispetto alle cose come stanno o come vengono date per inevitabili. Questa concezione della bellezza/arte ha senso solo in un universo politico: alla lettera nello spazio della città, nei costrutti organizzati, laddove comunichiamo in una cornice di riferimenti sociali e culturali. Se abitassimo remoti dagli esseri umani, immersi nella natura, non avremmo bisogno del dissenso, né di quel tipo di lame affilate usate da Zuleika e evocate da Spalletti. Ma fin quando il nostro posto è tra i nostri simili è necessario interrogarsi sulla bellezza come arte (e come dissenso). Oggi più che mai.

English text

Conversation whit Elena El Asmar and Pietro Gaglianò on the book “C’era una volta ed era celeste”

Edition La vita felice, in the collection Echi. www.lavitafelice.it

#paroladartista #intervistartista #intervistacritico #elenaelasmar #pietrogagliano #ceraunavoltaederaceleste #lavitafelice #echi

Parola d’Artista: Since Pietro in his consolation introducing this book of yours quoted a passage from Genesis I would also like to start from there: “In the beginning was the word…” it is written but in this case it seems more appropriate to say In the beginning was the image since the book opens with a sequence of reproductions of your works on paper. How did this book come about and why?

Elena El Asmar: The idea of doing this book was born with Pietro Gaglianò, in the summer, by the pool, or maybe before, perhaps while we were both looking at the clouds of the same sky, albeit in geographically different regions.

Pietro was familiar with the work on watercolours because I had exhibited some of them a few years ago in an exhibition, which he curated, in Venice and, at the same time, he had had the opportunity to read the texts that make up the book.

So, in one of our many conversations, we began to hypothesise what it would be like to transform images and words into a narrative experience, which is what books are all about.

I thus began to move images and words around on paper, mainly according to formal needs. The commissioning of a first draft of the book coincided with a visit to the studio of Gerardo Mastrullo and Ginevra Quadrio Curzio of the publishing house La Vita Felice, who had come to discuss with Luca Pancrazzi and me a new project they wanted to initiate, namely to start a collaboration with a number of artists for the creation of their stand at the various book fairs, each time presenting a publication concerning the artist involved.

The mock-up I had placed on the table caught their attention and interest and so, in addition to the “Stanze d’Artista” project at the 2023 Rome Book Fair “Più libri più liberi”, a new series from the publishing house called “Echi” was also inaugurated.

P.d’A.: From the beginning, this book takes us on a journey and cultivates the dimension of reverie by inviting the reader to look through a kaleidoscope of images, colours, scents and flavours that generate an enveloping, sensual place of great fascination. How important is your relationship with Gaston Bachelard?

Pietro Gaglianò: The space of the rêverie, as a place of unexpected connections, of invention that proceeds by openings and not by constructions, by free associations that dispense with the conditioning of the Western tradition, all this has, in fact, been present in Elena’s work for many years. The works collected in this book are perhaps those in which this link is most evident, not least because of the continuous slippage between the two mediums: from word to image and, circularly, from image to word. Bachelard (along with other thinkers even remote from the debate on the phenomenology of art) is certainly an important reference point for his poetics, but his interpretation is always heretical, it is always a “making one’s own”, indifferent to philological purity, to the coherence of the study.

P.d’A.: In this book, the idea of time seems to me to have its own importance, sometimes openly declared other times more subtly but always present. Then there are various aspects that similarly return like the threads of a warp that weave together to draw a vast landscape, which like a puzzle is made up of multiple fragments/pieces. I wanted to ask you how important was the idea of making order in the construction of the structure with which you concatenated the poems and images that make up this book?

E.E.A.: The structure and succession of the images, first, and of the texts, then, suggests a certain path that I imagined the eye could take as it leafed through and read the book. The watercolours all have as their reference precise places that I have frequented in recent years and that compose a sort of autobiographical portrait of me in images.

The texts are also affected by this need to tell my story through images where colours and signs become words, pauses, spacing.

Finally, in a dimension that is more sentimental than logical, the words and images bind together at their own discretion, and at the discretion of the viewer, as if they were a sounding board for each other.

P.d’A.: Has poetry been with you for a long time or is it a recent discovery?

E.E.A.: Every time I light a cigarette.

P.d.A.: You are a poetry reader, which poets do you read?

E.E.A.: This morning, weeping, like Dino Campana I swore an oath to the blue, then I saw Emily Dickinson’s birds and snow, and I had breakfast with sultana buns and apples because I too am sick with love like Solomon in the Song of Songs. There will be many more visits today between now and evening.

P.d.A.: Pietro, reading your consolation reminded me of a statement by Ettore Spalletti: Beauty is like a blade cut like a beautiful woman crossing a square. Why do you think it is necessary to continue questioning the nature of beauty?

P.G.: Beauty in any discourse on art is always a metaphor for something else. In a way we could say that beauty is itself art, if it is good art: it is the vehicle for an aesthetic or cognitive experience of dissent. I mean that art (or beauty) allows one to recognise something of the world that the world (the grey administration of the world) does not intend to show or is unable to show. Those who authentically experience beauty (or art) change their thinking, even if only slightly, and activate forms of resistance, of antagonism to things as they are or as they are given as inevitable. This conception of beauty/art only makes sense in a political universe: literally in the space of the city, in organised constructs, where we communicate within a framework of social and cultural references. If we lived remote from human beings, immersed in nature, we would not need dissent, nor the kind of sharp blades used by Zuleika and evoked by Spalletti. But as long as our place is among our fellows, it is necessary to question beauty as art (and as dissent). Today more than ever.

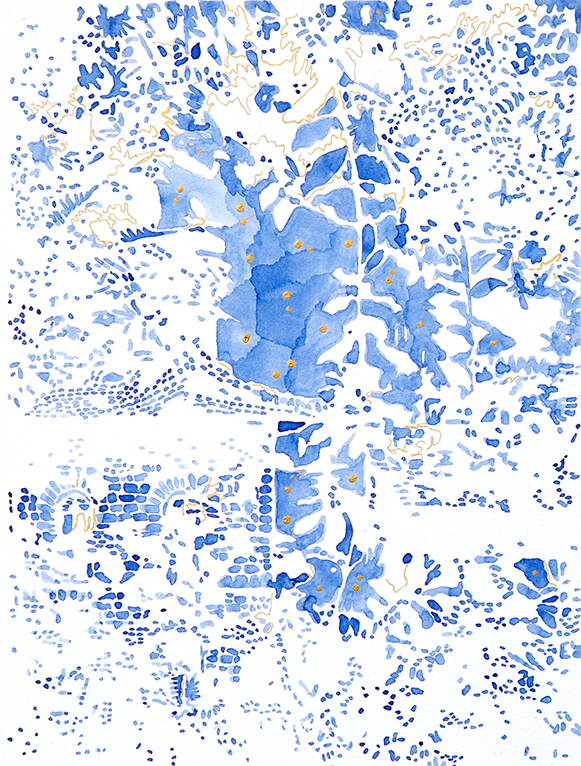

Siena 2023

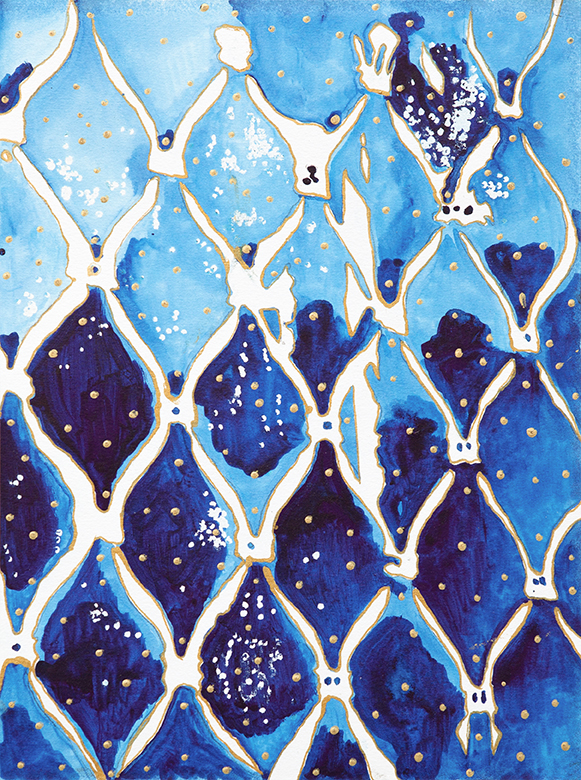

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

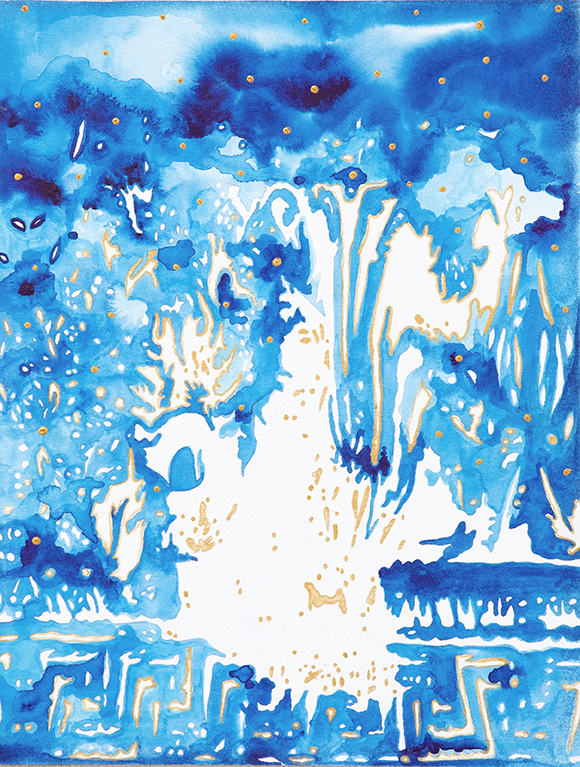

Siena 2023

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

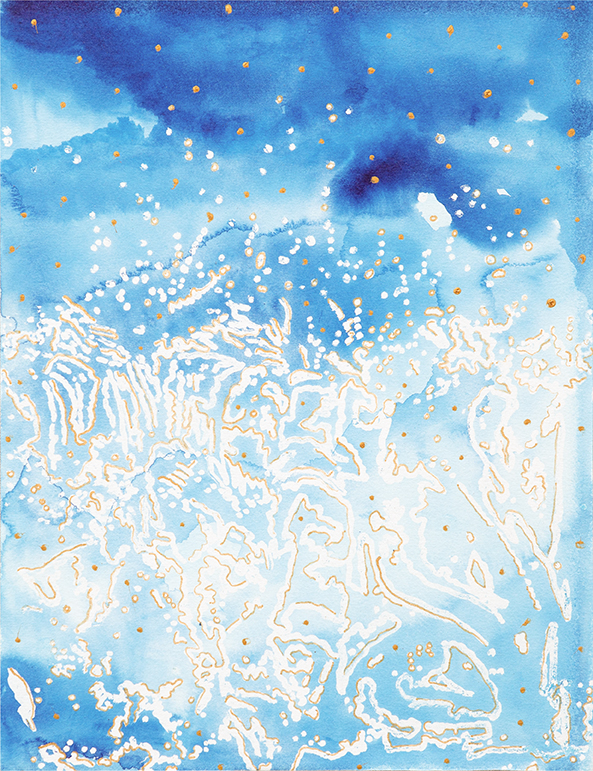

Siena 2023

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

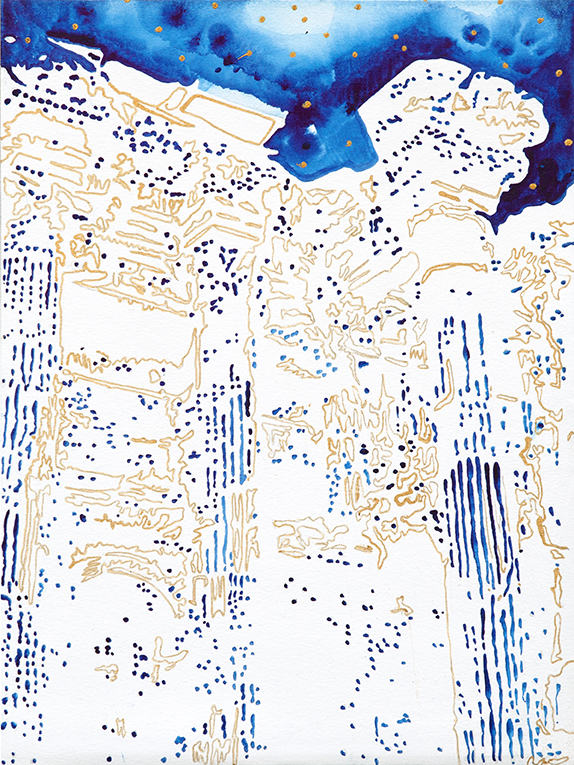

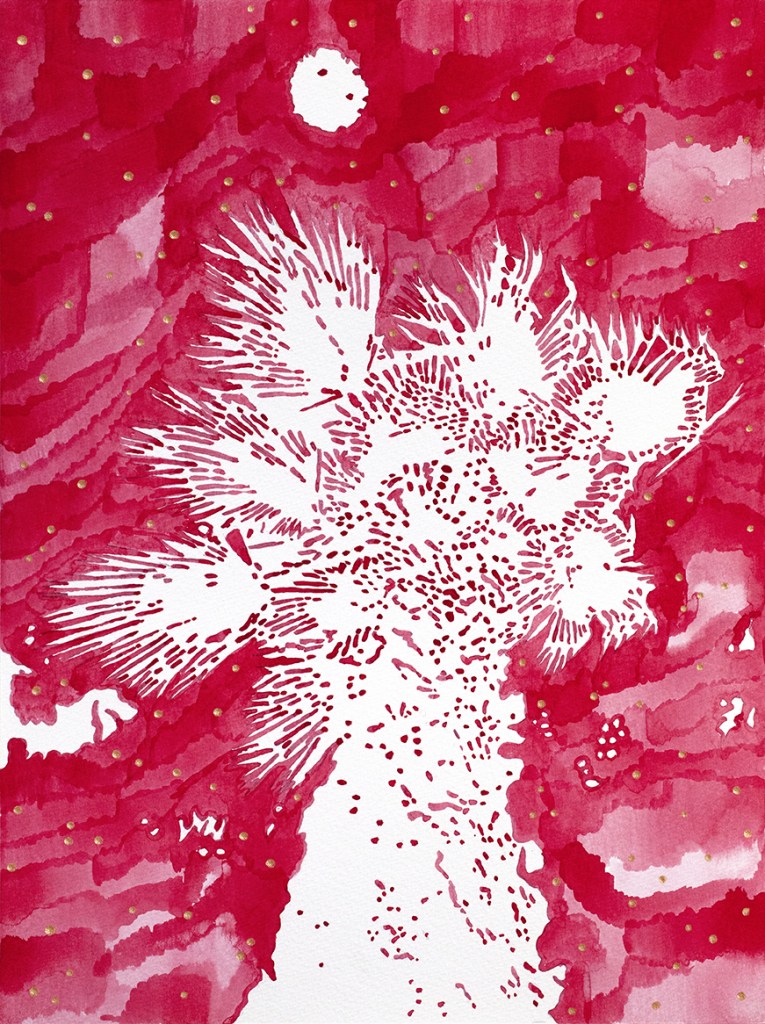

Baalbek 2022

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

Baalbek 2021

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

Venezia 2020

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

Santa Cesarea Terme 2023

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm

Otranto 2023

Acquerello e pennarello oro su carta 32x24cm