(Scroll down for English Text)

#paroladartista #disegno #drawing #paolaricci

Parola d’Artista: Che importanza e che ruolo ha nel tuo lavoro il disegno?

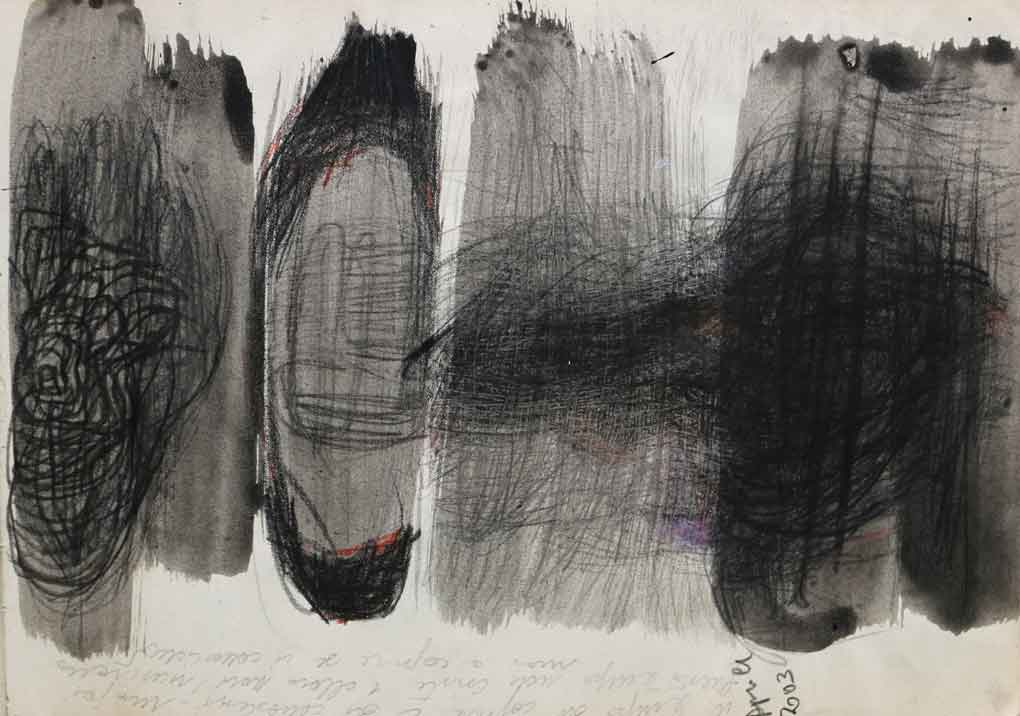

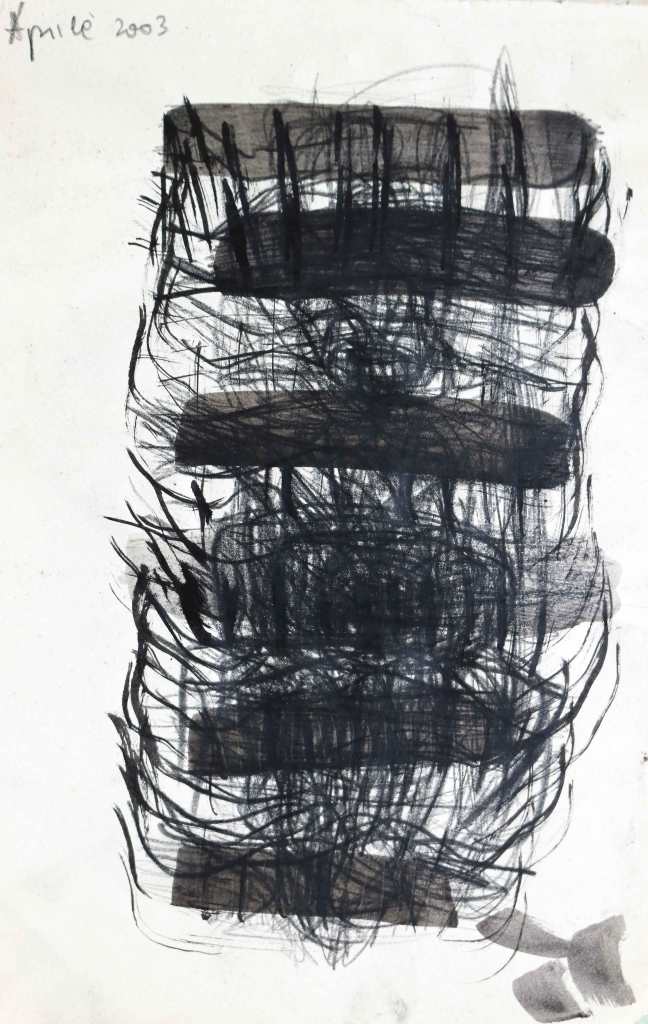

Paola Ricci: Il disegno e il suo concetto è sempre presente nella mia ricerca, è una forma d’azione continua e meditativa che tocca i supporti che non siano solo la carta, ma anche superfici fotografiche e scultoree.

In questo mio costante e coerente lavoro di ricerca il disegno assume il senso di variabilità in una costanza.

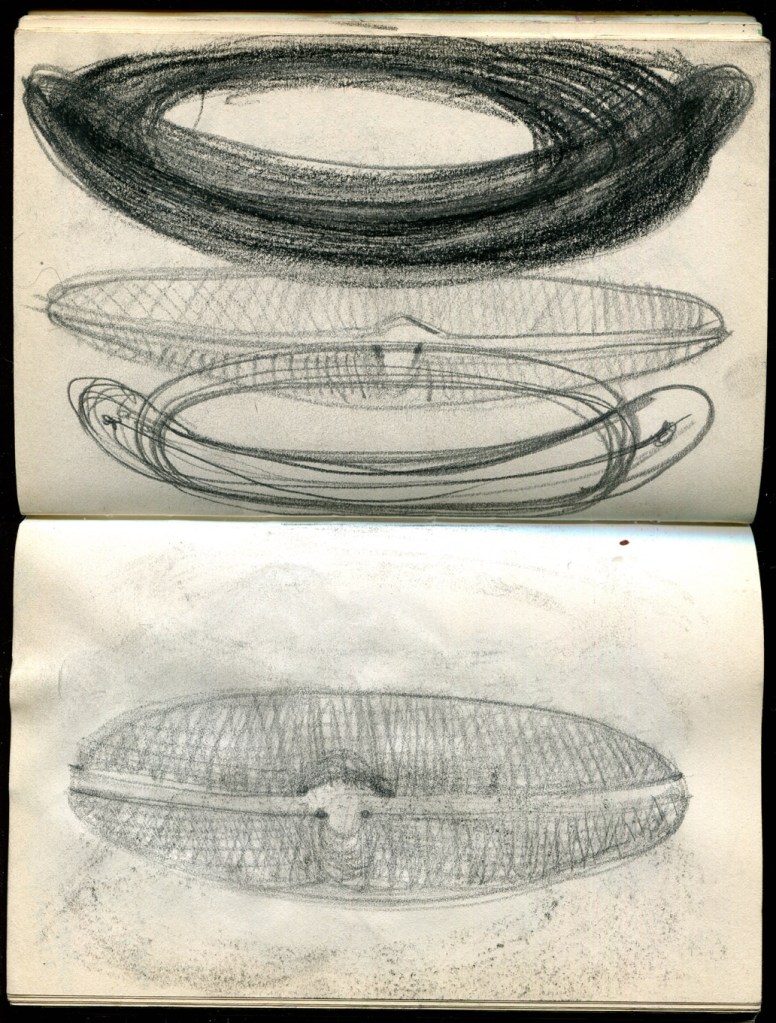

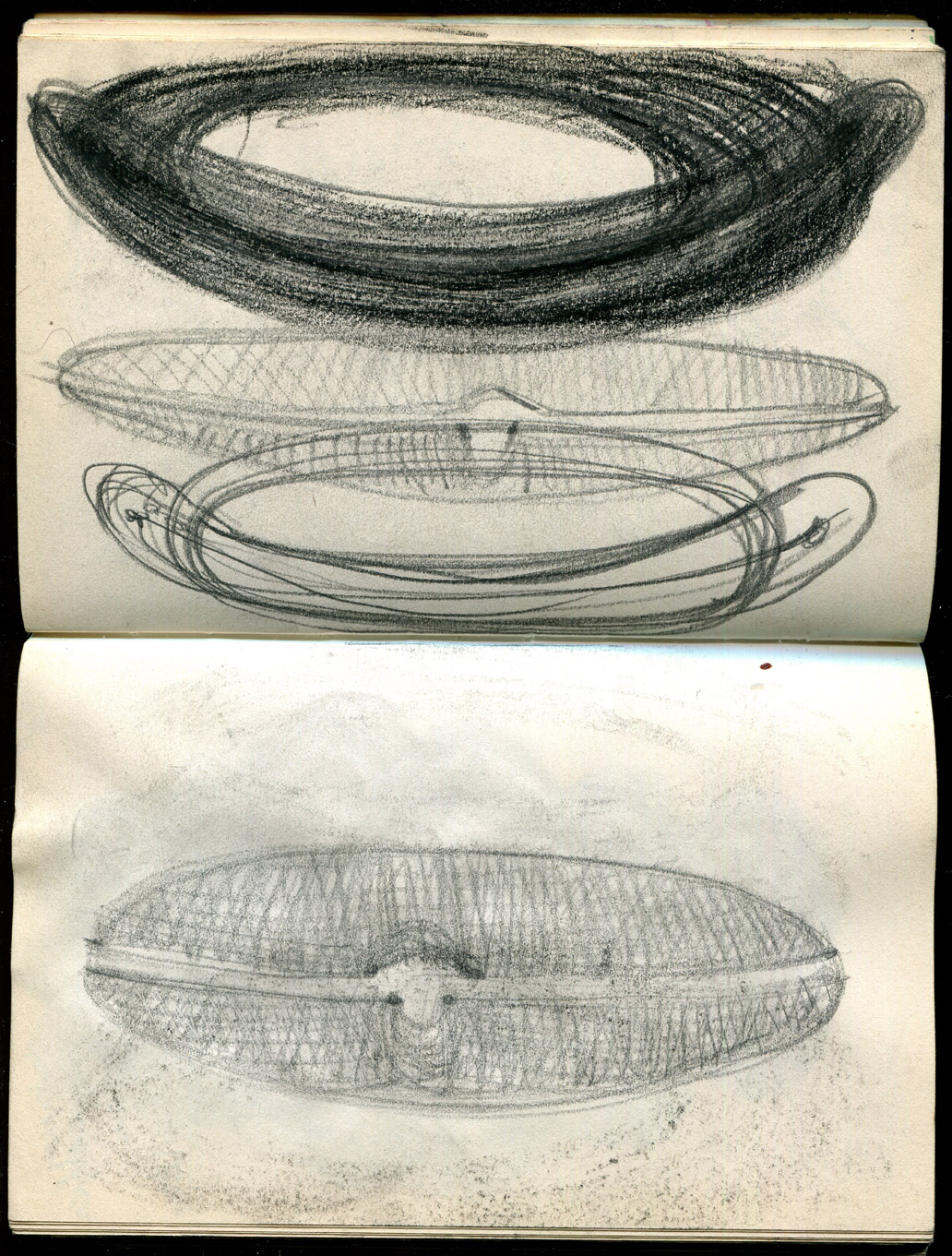

Gli oggetti materiali si spostano sulla terra perché hanno forma che può rotolare, soggiacere al movimento, al ritmo del tempo in una frequenza che diminuisce quando la durata temporale e la terra corrono parallelamente. Allora le estremità di una forma disegnata si arrotonda, nel piegarsi alla possibilità, che la materia diventi tridimensionale.

L’atto è improvviso, ma come tale è decisivo e voluto, per dare consistenza alla materia.

I movimenti lenti possono essere paragonati a dei paesaggi rilassati, che si manifestano davanti alla contemplazione di una realtà necessaria. A volte si ha la sensazione che questo guardare sia dato dalla possibilità di tornare indietro e riagganciarsi a un dettaglio che sembrava andato perso. Allora se il foglio su cui si è segnato un disegno rimane nascosto nel tempo, quello che avviene dopo è la conseguenza di questo non guardare. Perché lo sguardo dell’artista non è mnemonico come l’accumulo di nozioni che sono inanellate per esprimere concetti, ma è la memoria dell’intuizione. Quello scarto è l’improvviso, che riapparirà inaspettato, come conseguenza del tempo di decantazione.

Riagganciare lentamente quello che è stato fatto è parte del processo dell’esecuzione, tale che il tempo è la dimensione curva per cui l’inizio è conseguenza della fine. Siamo come in una sfera aperta, l’artista si trova a correrci dentro senza perdere l’orientamento, che è sempre come nel camminare su una spiaggia. Si parte dalla terra, per incontrare il fluido mare e ritornare poi su altra terra. Il Tempo può demonizzare gli oggetti, ma se si volge lo sguardo pronunciando i dettagli, allora sarà il brillare della forma. Le griglie disegnate possono essere la scansione del tempo. Determinano una sovrapposizione di diversi livelli di segni, tali che ognuno può essere conglobato in una forma apparentemente unica.

La sovrapposizione del segno come invece forma di accumulazione verticale determina la confluenza di segno e cromia che evapora e allude a una rarefazione del campo d’azione. Ecco che il tempo diventa liquido e non per questo atemporale, assume la somma d’infiniti scatti dello stesso momento che svaniscono nelle particelle che stanno tra loro a contatto. Il chiaro e lo scuro diventano quindi una sorta di scansione del tempo dove la terra si può distribuire in modo diverso in base alla quantità di materia che contribuisce alla costruzione di un disegno-scultura. Il segno è morbido e duro, senza che il contatto reale con la pelle si possa appoggiare sulla linea del disegno, ma la determinazione che esso diverrà una scultura permette che sia raggiunta una sensazione tattile anche solo attraverso lo sguardo sulla carta.

“Tutto ciò che vedi nel mondo intorno a te si presenta ai tuoi occhi soltanto come un insieme di macchie di colore variamente ombreggiate. Alcune di tali macchie presentano al loro interno dei tratti o una trama…” John Ruskin

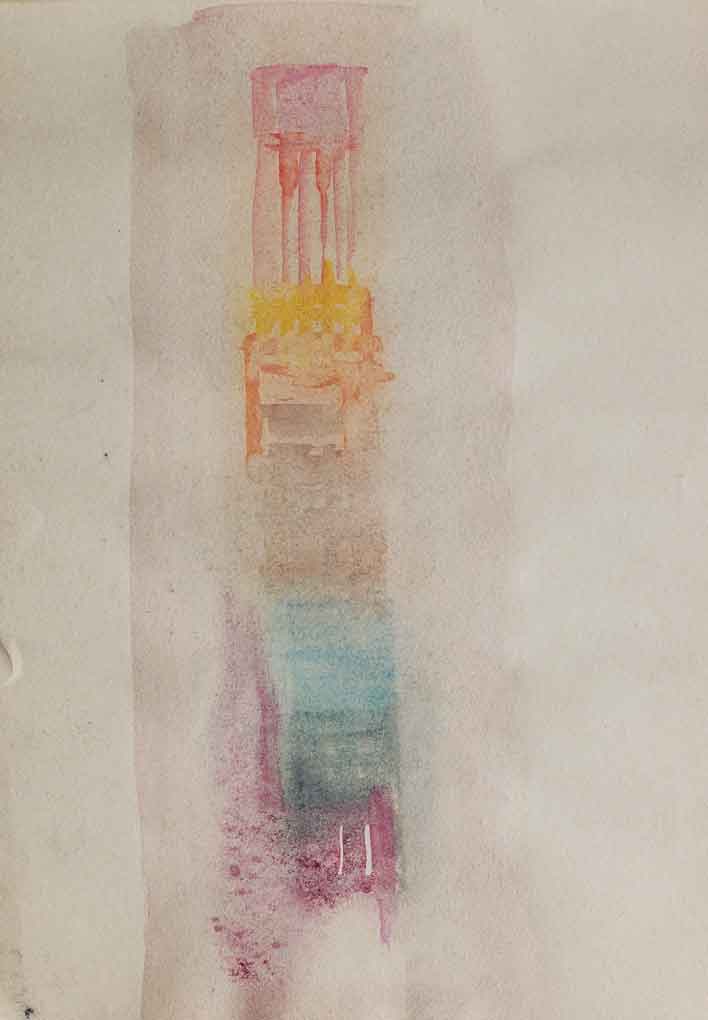

Camminare per le vie di Parigi diventa un’arte dell’osservazione, di come la luce disegna su un supporto fotografico. Nel silenzio di Parigi vi era solo il risultato di una quiete apparente e davanti alla Sorbonne in rue Victor Cousin non passavano che poche persone come si affrettassero a raggiungere casa e in quella via in quel che rumoreggia a quell’ora erano i motorini degli ultimi studenti che si lasciavano alle spalle letture avvincenti o indecifrabili.

Quello che stavo cercato di catturare era quella scia di luce rossa, sospesa nell’aria buia, era quello che il passato si era lasciato dietro perché l’inizio era lì in quella via solitaria, ma gremita di ombreggiature colorate che avrebbero disegnato il nuovo viaggio a Parigi. La fotografia è come un mezzo per disegnare ciò che vediamo.

Così il disegno, la forma e il colore sono solo dei termini-strumenti come possono essere il ritmo e il significato, occorre stemperarli con successioni conoscitive e operative che superano lo stereotipo e attingono a un’applicazione maggiormente interdisciplinare dove l’attenzione si muove parallelamente al nostro e al loro emotivo.

Alcuni materiali come carta, stoffa, polistirolo, spugna e legno, assumono un’amplificazione maggiore quando enunciamo anche le azioni che si possono compiere su di essi. Il nostro agire con strumenti diversi sensibilizza il segno e la superficie. Usare uno strumento come il pennino su una carta liscia produrrà un segno che assumerà maggiore espressività se fatto su una carta ruvida, e poi se si usa un pastello a olio sulla carta ruvida avremo ancora più espressività che se lo si userà su una carta liscia.

Pensiamo ai segni fluidi di Matisse, a quelli pastosi di Van Gogh, agli acquerelli liquidi e trasparenti di Klee, le pennellate veloci e tremolanti di Monet o lo sgocciolamento di Pollock.

Le stesse azioni, come dipingere col pennello, cambiano su diversi materiali e produrranno un effetto diverso e una diversa espressività. Alcuni materiali possiamo strapparli, come la carta, su altri possiamo inciderli, come il legno o addirittura bruciarli, la carta la possiamo cucire come la stoffa, mentre incolleremo sia carta, che legno e le stoffe e polistirolo. Le spugne le potrò usare come punzoni come il polistirolo.

I gesti e i movimenti sono molti e la loro conoscenza può essere aiutata dall’individuazione dei relativi vocaboli che li descrivono, dicendo “con molta pressione” s’immagina subito come la nostra mano imprimerà un peso e una forza maggiore rispetto al normale uso.

L’atteggiamento astratto può trovarsi in un’attinenza tra concetto di opera e la sua realizzazione che albeggia in una grande dicotomia che alimenta l’artista silente che è il “vero apparente”; se il senso più completo è forse il gusto, io aggiungo che toccare è il senso più piccolo che s’intrufola negli anfratti del silenzio.

Sono le opposizioni non circoscrivibili che determinano quello che sarà il superare il reale con il velato, il dubbio dell’esistenza stessa, dove l’arte vera, però non si schiera e non raggiunge nessun apice che è già quello che è; non ha bisogno di citazioni e di declamare altro che già è insito dentro. Questa forza propulsiva è l’inizio della creazione artistica e il disegno è una metafora, non contaminata, che detta i possibili sviluppi su altre manifestazioni artistiche.

La mia ricerca è sempre stata rivolta verso gli elementi/azioni della natura che pongono all’uomo occidentale degli interrogativi di cui analizza difficilmente.

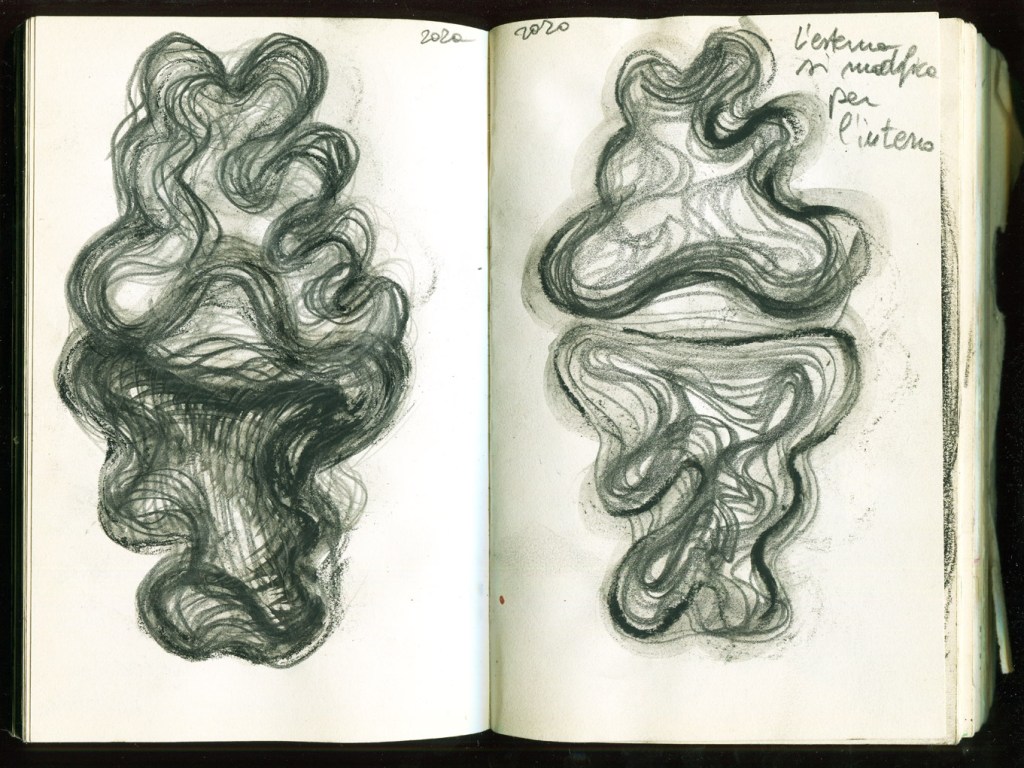

L’aria che ci circonda è qualcosa che occupa fisicamente uno spazio non visibile che l’uomo occidentale riconosce come un vuoto-assenza, e invece io lo riconosco come vuoto di essenza di pieno, “emanazione di vita”; il nostro corpo muovendosi sposta l’aria e occupa dei vuoti in cui noi entriamo e che esistono invisibili.

Compio un lavoro “nel limite” tra il disegno e la scultura, tra il segno e il volume, tra la linea lasciata e l’aria spostata. Lavoro su un’idea d’immateriale, come se ciò che faccio possa anche non esistere o breve vita, o fragilità di vivere, come se la scultura sia il mezzo per spostare l’aria che la circonda più che costruire un oggetto vero e proprio. Il disegno e la scultura muovono lo spazio in cui appaiono. Voglio che il mio lavoro possa indurre lo spettatore a sentire “come“ vede i lavori artistici, non quanto “cosa” vede.

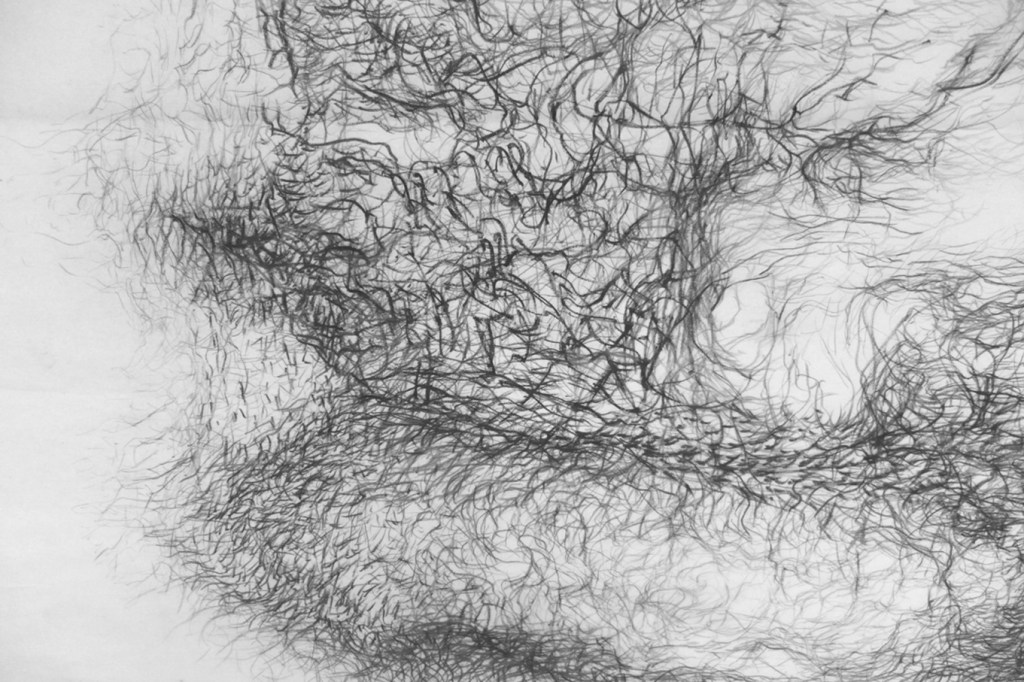

L’aria sposta l’albero e non lo fa percepire bloccato alla terra, ma come un continuo movimento che oscilla nella sua fragilità e come tale “capovolto”, dove il leggero sta in basso e il pesante sta in alto. La natura estetica di poter contenere gli opposti e le contraddizioni per dare una forza all’immagine che arriva ed annullare la forma.

Concludo con questo lavoro presentato al Museo di Emilio Greco e poi al MADXI di Latina.

“Filo d’Arianna” che non compie una rivoluzione, nessuna tragedia, nessuno spaccato con la tradizione. E’ in contatto con l’azione sul vuoto, col segno e con l’effimero del segno, che c’è, ma può scomparire, può essere “segnato”, ma può essere cancellato in un attimo. L’arte c’è, ma scompare è un atto, ma può ripetersi in modo diverso. Ci fa riflettere che nell’arte il fare, forse non basta. L’arte è trasformativa e questo è l’artista, che si assume di accogliere questo passaggio, accettare che l’artista, facendo arte, trasforma tutta la sua vita senza compromessi senza allusioni, avviene e basta.

Qui l’idea è arte, ma anche la tecnica di porre è arte, come la sua eliminazione e ripetere i gesti è la TECNICA del disporre.

“Filo d’Arianna è costituito da elementi a se stanti. Riconducibili a forme antropomorfiche di linee spezzate e sinuose. Rugosità interrotte perché il ramo non è più ancorato al tronco. Allora la fronda è mutata, nuova sistemazione si colloca in un altro luogo. Filo d’Arianna diventa: “Elementi di tronchi d’alberi disposti in un modo destrutturato. Essi sono posti e riposti in modo diverso e in tempi differenti, come un continuo fluire dell’azione dell’artista del disegnare”.

English Text

On drawing Paola Ricci

#paroladartista #disegno #drawing #paolaricci

Parola d’Artista: What importance and role does drawing play in your work?

Paola Ricci: Drawing and its concept is always present in my research, it is a continuous and meditative form of action that touches supports that are not only paper, but also photographic and sculptural surfaces.

In this constant and consistent research work of mine, drawing takes on the sense of variability in a constancy.

Material objects move on the earth because they have form that can roll, subject to movement, to the rhythm of time in a frequency that decreases when time duration and the earth run parallel. Then the ends of a drawn form round off, in bending to the possibility, that matter becomes three-dimensional.

The act is sudden, but as such it is decisive and intentional, to give substance to matter.

The slow movements can be compared to relaxed landscapes, which manifest themselves before the contemplation of a necessary reality. Sometimes one has the feeling that this looking is given by the possibility of going back and reconnecting with a detail that seemed lost. So if the sheet on which a drawing has been marked remains hidden in time, what happens afterwards is the consequence of this not looking. Because the artist’s gaze is not mnemonic like the accumulation of notions that are ringed to express concepts, but is the memory of intuition.

That gap is the suddenness, which will reappear unexpectedly, as a consequence of the settling time.

Slowly catching up with what has been done is part of the process of execution, such that time is the curved dimension whereby the beginning is a consequence of the end. We are like in an open sphere, the artist runs into it without losing his orientation, which is always like walking on a beach. One starts from the earth, to meet the fluid sea and then return to other land. Time may demonise objects, but if one turns one’s gaze by pronouncing the details, then it will be the shining of form. The grids drawn can be the scanning of time. They determine an overlapping of different levels of signs, such that each can be conglobated into a seemingly unique form.

The superimposition of the sign as a form of vertical accumulation determines the confluence of sign and colour that evaporates and alludes to a rarefaction of the field of action. Here time becomes liquid and not timeless, it assumes the sum of infinite shots of the same moment that vanish in the particles that are in contact with each other.

The light and dark thus become a kind of scanning of time where the earth can be distributed differently according to the amount of material that contributes to the construction of a drawing-sculpture. The mark is soft and hard, with no real contact with the skin to rest on the line of the drawing, but the determination that it will become a sculpture allows a tactile sensation to be achieved by just looking at the paper.

“Everything you see in the world around you presents itself to your eyes only as a collection of variously shaded patches of colour. Some of these spots present within them features or a texture…” John Ruskin

Walking through the streets of Paris became an art of observation, of how light draws on a photographic medium. In the silence of Paris there was only the result of an apparent stillness and in front of the Sorbonne in rue Victor Cousin only a few people passed by as if hurrying to get home, and in that street what was noisy at that hour were the mopeds of the last students leaving behind them compelling or indecipherable readings.

What I was trying to capture was that trail of red light, suspended in the dark air, it was what the past had left behind because the beginning was there in that lonely street, but filled with coloured shadows that would draw the new journey to Paris. Photography is like a medium for drawing what we see.

So drawing, form and colour are only terms-instruments as rhythm and meaning can be, we need to dilute them with cognitive and operational successions that go beyond the stereotype and draw on a more interdisciplinary application where attention moves in parallel with our and their emotional.

Certain materials, such as paper, fabric, polystyrene, sponge and wood, take on greater amplification when we also enunciate the actions that can be performed on them. Our acting with different tools sensitises the mark and the surface. Using a tool such as a nib on a smooth paper will produce a sign that will take on greater expressiveness if done on a rough paper, and then if we use an oil pastel on the rough paper we will have even more expressiveness than if we use it on a smooth paper.

Think of Matisse’s fluid marks, Van Gogh’s mellow ones, Klee’s liquid and transparent watercolours, Monet’s fast and flickering brushstrokes or Pollock’s dripping.

The same actions, like painting with a brush, change on different materials and produce a different effect and expressiveness. Some materials we can tear, such as paper, on others we can engrave, such as wood or even burn them, paper we can sew like cloth, while we will glue both paper and wood and polystyrene. Sponges can be used as punches like polystyrene.

The gestures and movements are many, and knowledge of them can be aided by identifying the relevant words that describe them, saying ‘with a lot of pressure’ immediately imagines how our hand will impart a greater weight and force than normal.

The abstract attitude can be found in a connection between the concept of the work and its realisation that dawns in a great dichotomy that nourishes the silent artist who is the ‘real apparent’; if the most complete sense is perhaps taste, I would add that touching is the smallest sense that sneaks into the recesses of silence.

It is the non-circumscribable oppositions that determine what will be the overcoming of the real with the veiled, the doubt of existence itself, where true art, however, does not take sides and does not reach any apex that is already what it is; it does not need quotations and declamation other than what is already inherent within. This propulsive force is the beginning of artistic creation and drawing is a metaphor, untainted, that dictates possible developments in other artistic manifestations.

My research has always been directed towards the elements/actions of nature that pose Western man questions that he hardly ever analyses.

The air that surrounds us is something that physically occupies a non-visible space that western man recognises as a void-absence, and instead I recognise it as a void of essence of fullness, an ‘emanation of life’; our body moves the air and occupies voids that we enter and that exist invisibly.

I work ‘in the limit’ between drawing and sculpture, between sign and volume, between the line left and the air moved. I work on an idea of the immaterial, as if what I do might not even exist or be short-lived, or fragile to live, as if the sculpture is the means of moving the air around it rather than building an actual object. Drawing and sculpture move the space in which they appear. I want my work to make the viewer feel “how” they see the artwork, not how much “what” they see.

The air moves the tree and does not make it perceive it as being stuck to the earth, but as a continuous movement that oscillates in its fragility and as such ‘upside down’, where the light is at the bottom and the heavy is at the top. The aesthetic nature of being able to contain opposites and contradictions in order to give a force to the image that arrives and cancels the form.

I conclude with this work presented at the Emilio Greco Museum and then at MADXI in Latina.

“Filo d’Arianna” makes no revolution, no tragedy, no break with tradition. It is in contact with the action on the void, with the sign and with the ephemerality of the sign, which is there, but can disappear, can be ‘marked’, but can be erased in an instant. Art is there, but disappearing is an act, but it can be repeated in a different way. It makes us reflect that in art, doing is perhaps not enough. Art is transformative and it is the artist, who takes it upon himself to accept this passage, to accept that the artist, by making art, transforms his whole life without compromise without allusion, it just happens.

Here the idea is art, but the technique of placing is also art, as is the elimination of it and repeating the gestures is the TECHNIQUE of disposition.

“Filo d’Arianna” consists of elements in their own right. They can be traced back to anthropomorphic forms of broken, sinuous lines. Roughness interrupted because the branch is no longer anchored to the trunk. Then the branch has changed, new arrangement is placed in another place. Filo d’Arianna becomes: “Elements of tree trunks arranged in a deconstructed manner. They are placed and repositioned in different ways and at different times, like a continuous flow of the artist’s drawing action’.