(Scroll down for English version)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #santissimi

Parola d’Artista: Per la maggior parte degli artisti, l’infanzia rappresenta il periodo d’oro in cui iniziano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per voi?

Sara Renzetti: sicuramente sin da piccola si è manifestata una certa sensibilità nel guardare le cose. Ricordo che le osservavo come per ascoltarle, per decifrare quel che si mostrava ai miei occhi, è come se le persone, gli oggetti e tutto quello che appariva fosse continuamente visitato ed interpretato da me.

Come se ogni cosa non esistesse in sé, spettava a me farla vivere a modo mio, e questa lettura che facevo del mondo non necessariamente doveva essere raccontata o registrata, la vivevo e basta. Non utilizzavo nessun mezzo artistico per fermarla, non mi era nemmeno venuto in mente di scrivere o di disegnare. Vivevo questo mio mondo in totale solitudine e silenzio e questo mi bastava.

All’età di tredici anni credo di aver iniziato a lasciare le prime tracce visibili, così, in modo molto naturale avevo iniziato a scrivere pensando di disegnare e questi disegni sembravano talmente simili a quelle visioni che mi convinsero a continuare.

Avevo iniziato a capire come fare e cosa farne di tutte quelle impressioni che prima semplicemente vivevo per scoprire pian piano che non ero la sola.

Sono comunque convinta che sia stata la visione solista e recondita ad aver risolto quell’ immediato vivere a cui corrisponde ogni opera realizzata. Un’ immediato vivere che riguarda il presente in cui vive l’artista ma che si rivolge sempre al prossimo a cui è data l’opera.

Antonello Serra: sicuramente l’infanzia ha rappresentato un periodo decisivo per la mia formazione.

Ero solito usare un termine, da me inventato, per indicare una sorta di stato di grazia che percepivo; questo termine era “Antonellare”. Il mio nome declinato come verbo!

Qui dentro c’era tutto il mio mondo, tutte le cose che mi rendevano felice, i giochi soprattutto… ma tra i giochi ce n’era uno, il disegno, che era quello che mi rendeva più sereno e allo stesso attivava di più la mia immaginazione dandomi una specie di euforia.

Non era un cercare rifugio da una brutta situazione ma piuttosto trovarsi a fare un qualcosa che ti regalava la felicità.

Col passare degli anni la passione è cresciuta e si è trasformata in mille modi, ma l’atteggiamento è rimasto sempre quello.

P.d’A.: Quali studi avete fatto?

Santissimi: Sara, Liceo Artistico e Accademia di Belle Arti, sezione pittura.

Antonello, Liceo Artistico, Architettura e Disegno Industriale.

P.d’A.: Ci sono statti degli incontri importanti durante la vostra formazione?

Santissimi: La filosofia è stata molto formativa, nel senso che ha dato spunto a moltissime delle nostre opere. Non abbiamo una formazione filosofica ma abbiamo capito che il nostro lavoro inizia sempre da un parlare tra di noi, un continuo parlare tra di noi che a furia di parlare giunge e raggiunge un’incontro materico in cui la realtà sembra essere accessibile, concettualmente tangibile e paradossalmente rappresentabile. Le nostre opere nascono sempre da questo incontro di forme che hanno dialogato in precedenza e che probabilmente continuano a dialogare ogni qualvolta qualcuno le osserva.

P.d’A.: Quando avete iniziato a lavorare insieme?

Santissimi: Abbiamo iniziato nel 2005 realizzando un hotel d’arte contemporanea in Sardegna, all’epoca eravamo Antonello Serra e Sara Renzetti.

Nel 2009 è nata la nostra prima opera “Settimo Cielo” e da lì la nostra ricerca si è firmata Santissimi.

P.d’A.: Che cosa vi ha unito sul piano artistico?

Santissimi: Siamo uniti sul piano umano, l’arte viene di conseguenza e subito dopo.

P.d’A.: L’idea di usare il corpo umano, facendo leva sulla sua brutale fisicità e sullo scandalo causato dalla nudità o dal mostrarne le interiora o addirittura le sue feci, ha degli illustri predecessori nella storia dell’arte recente Ron Mueck, Damen Hirst che non ha mai fatto segreto di voler fare la stessa cosa che ha fatto sezionando il cadavere di un cavallo con un corpo umano lamentandosi solo del fatto di non essere riuscito a trovarne uno disponibile o Jenny Saville, e i fratelli Chapman solo per citarne alcuni… In che cosa il vostro lavoro si differenzia da quello di questi artisti?

Santissimi: Non abbiamo mai fatto leva sullo scandalo e non siamo interessati a descrivere in che cosa il nostro lavoro si differenzia dal lavori degli artisti citati. La domanda presuppone un confronto e ogni confronto tra due cose simili o totalmente diverse presuppone un risultato stabilito in precedenza. Date le premesse è tutto già stato avviato se non definitivamente concluso. Oltretutto cercare le differenze non porterebbe a comprendere il lavoro ma solo a trovare una risposta alla domanda, una risposta che sarebbe solo relativa al contesto e quindi totalmente incompleta e forviante.

Il lavoro dell’artista va assorbito e per questo ci vuole tempo, va approfondito e per questo ci vuole tempo, va liberato dal confronto e per questo ci vuole amore, esattamente quello che dovremmo fare con noi stessi per volerci bene: liberarci dal confronto con gli altri.

Apprezziamo molto il lavoro di Ron Mueck, Damien Hirst, Janny Saville e dei fratelli Chapman ma non perché fanno leva sulla brutalità fisica e tanto meno sullo scandalo ma perché mostrano parte della realtà che non viene esibita, una realtà che esiste ma che si evita di vedere. Se questo produce scandalo è perché il nostro vivere insieme si basa sulla volontà di ignorare piuttosto che di comprendere. Lo scandalo nasce sempre da ciò che esiste ma che momentaneamente si esclude.

Se il brutto fa scandalo è solo perché in un dato momento o in una determinata circostanza domina il bello, niente di più di questa semplice considerazione.

Abbiamo sempre usato il corpo per rappresentare l’uomo in assoluto, assoluto nel senso del suo valore stabile, senza alcun riferimento al quotidiano, ovvero alle variabili presenti nel quotidiano e in questo ci sentiamo totalmente differenti dagli artisti della scena iperrealista che invece cercano di rappresentare proprio questa variabile, questa instabilità.

I nostri corpi sono nudi semplicemente perché il concetto di uomo è nudo, l’uomo è nudo e non vestito.

Non siamo mai stati associati ad uno scultore come Michelangelo, che rappresentava ugualmente l’uomo nudo, questo perché spesso si confonde la tecnica e il materiale utilizzato con l’etica e l’estetista dell’opera. Ci si affida troppo all’impatto e questo fa parte della superficie, la così detta superficialità.

P.d’A.: L’idea di messa in scena vi interessa? Volevo chiedervi di spiegare la vostra idea di lavoro site specific legata per esempio all’interventi fatto nel ex macello di Cagliari ?

Santissimi: L’idea di messinscena di origine teatrale ci interessa molto perché ci siamo sempre occupati dell’ allestimento delle nostre mostre, curandole direttamente in tante occasioni. Nel caso della personale All’Exmà di Cagliari abbiamo pensato il percorso della mostra come un’immersione nel nostro modo di pensare: tanti corpi carnali che si esponevano alla vista come simboli in cui riflettersi, come segni in cui esercitare il pensiero, come immagini (di) ciò che sfugge.

La mostra si sviluppava sia nella sala interna che lungo la facciata esterna.

Il percorso nella sala interna inizia con una forte prepotenza corporale in cui le sculture, anche se filtrate, sezionate o migrate, sono ancora ben riconoscibili, per poi finire nel ricordo vago della massa informe che alla fine del percorso costringeva a guardarsi dentro più che fuori. Una grossa massa di carne strozzata da una corda veniva giù dal soffitto circondata da 120 mosche svolazzanti per aria che, silenziose, come possono essere tante stelle nel cielo, terminavano il pellegrinaggio con una semplice indicazione: qualcosa è appena andato via trasformandosi in qualcos’altro. Era la fine di un percorso in cui avevamo impiegato tanto tempo a cancellare gli occhi, le mani, le gambe, le braccia, i piedi, il corpo tutto, per ritrovarci nelle forme più semplici, essenziali e tra gli spazi più grandi, aperti.

Per quanto riguarda il lavoro esterno, dal titolo “Rosa Rosae Rosae… “un uomo può uccidere un fiore, due fiori, tre… ma non può contenere la primavera” esposto lungo la facciata dell’exma, è stato il nostro primo intervento urbano.

L’Exma è stato un mattatoio sino al 1966. Il luogo e la sua storia hanno stimolato in noi una visione: abbiamo immaginato la struttura come una vasca di contenimento in cui, pressata e contenuta, si riversa la carne, venendo fuori dall’unica via d’uscita, gli archi della facciata.

Abbiamo pensato a questo lavoro anche come un intervento sulla città, che potesse avvicinare e coinvolgere più persone possibili, stimolare delle riflessioni e colorare di primavera tutta la via.

P.d’A.: Vi è mai capitato di incorrere nell’effetto speciale fine a se stesso che rapidamente esaurita la carica iniziale legata allo stupore per la sua manifattura resta li?

Santissimi: Ci è capitato di riceverlo come considerazione o come critica ma preferiamo evitare di star dietro a questo modo di vedere il mondo.

P.d’A.: Nel vostro lavoro c’è spazio per l’ironia e la trascendenza?

Santissimi: Certo, l’ironia è parte del dramma, non c’è ironia senza dolore.

Lo stesso vale per la trascendenza, tutte le opere superano la realtà, non sono mai dove tu le guardi, dove tu ci sei, sono sempre contemporaneamente qui e lì e non solo.

P.d’A.: Quando iniziate un lavoro avete già un’idea chiara di come si svilupperà che spazio ha l’imprevisto in quello che fate?

Santissimi: Abbiamo un’idea chiara di quello che vogliamo ottenere anche se ogni volta viene sempre smentita. Ormai abbiamo stabilito che l’idea è sempre e solo una bozza del risultato finale.

P.d’A.: Che tipo di dialogo cercate con lo spettatore che si trova davanti al vostro lavoro?

Santissimi: Un dialogo muto. Tante immagini e poche parole, anche perché le parole che noi stessi utilizziamo per accompagnare le opere sono trampolini in cui l’immagine salta, nel senso che va su e giù come può farlo un bambino che per gioco si solleva da terra per ricadere sul punto di partenza. Lo stesso vale per le sculture, quel salto c’è sempre ed è lì che va colta la nostra ricerca, va presa al volo, senza fermarsi all’ immagine, senza fermarsi alla rappresentazione perché è tutto perennemente in movimento, saltato appunto.

Non pretendiamo niente dallo spettatore, non pretendiamo che questo “salto” sia chiaro e compreso, ma sappiamo che quello che io vedo anche gli altri lo vedono. In ognuno di noi è già compreso tutto, in ognuno di noi è compreso anche l’altro, ed è qui, solo qui, che si fonda la nostra fiducia e il nostro dialogo con lo spettatore.

P.d’A.: L’idea di corpo politico ha una qualche importanza per voi?

Santissimi: Si, il corpo politico come corpo religioso, come corpo dell’ altro, come corpo di tutti, come corpo del tu, dell’io e del noi è fondamentale.

Corpo inteso come proprietà, come materia definita e definibile e politico inteso come organizzazione, attività ed esercizio è praticamente coincidente con il nostro lavoro.

In definitiva non c’è modo migliore per descrivere le nostre opere: materia organizzata di un corpo in esercizio.

P.d’A.: Secondo voi nell’arte contemporanea il sacro ha ancora una sua importanza?

Santissimi: Assolutamente si.

P.d’A.: Che cosa succede alle opere quando non c’è nessuno che le osserva, l’esistenza di un opera d’arte può prescindere dalla presenza di un osservatore?

Santissimi: La fisica quantistica ti direbbe di no. Noi ti diciamo di si, esistono a prescindere come esiste qualsiasi cosa, ma a questo non aggiungiamo nulla di più che un si. Un si molteplice perché va letto sia come avverbio che come pronome riflessivo, in cui “si” afferma ciò che il soggetto determina, e “si afferma” ciò che il soggetto determina.

P.d’A.: Alcuni artisti sono completamente dentro al loro lavoro, altri si mettono affianco c’è poi chi lo domina ossessivamente.. . Voi come artisti dove vi ponete nei confronti della vostra opera?

Santissimi: Ossessivamente affianco.

I Santissimi, duo formato da Sara Renzetti e Antonello Serra entrambi nati in Sardegna, hanno studiato a Firenze, accademia di belle arti lei (sezione pittura) e architettura lui (con specializzazione in disegno industriale). Non hanno una formazione scultorea, hanno imparato, nel campo aperto dell’esperienza, ad utilizzare i processi e i metodi della lavorazione del silicone affinché potesse rende visibile le loro immaginazioni.

Non avendolo mai deciso iniziano a lavorare insieme nel 2009 e tuttora rinnovano tale scelta finché le visioni continuano a coincidere. “Abbiamo iniziato a lavorare senza chiederci cosa volevamo fare. Le opere sono delle visioni e ogni opera è un passaggio successivo dell’opera precedente. Nessuna intenzione, nessun formalismo, nessuna casistica, nessuno stile…”

Definiscono le loro opere come possibili figure dell’eccesso, esercizi della mente, poesie visive, selfie percorribili sulla caducità dell’esistenza.

English text

Interview to Santissimi (Antonello Serra e Sara Renzetti)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #santissimi

Parola d’Artista: For most artists, childhood is the golden age when the first symptoms of a certain inclination to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too?

Sara: Certainly from a very young age, there was a certain sensitivity in looking at things. I remember observing them as if to listen to them, to decipher what was shown to my eyes, it was as if people, objects and everything that appeared was continually being visited and interpreted by me.

As if everything did not exist in itself, it was up to me to bring it to life in my own way, and this reading I did of the world did not necessarily have to be narrated or recorded, I just lived it. I did not use any artistic means to stop it, it did not even occur to me to write or draw. I lived this world of mine in total solitude and silence and that was enough for me.

At the age of thirteen I think I started to leave the first visible traces, so in a very natural way I had started to write while thinking about drawing and these drawings seemed so similar to those visions that they convinced me to continue.

I had begun to understand how to do and what to do with all those impressions that I had previously simply experienced, only to gradually discover that I was not alone.

However, I am convinced that it was the solitary and recondite vision that resolved that immediate living to which every work realised corresponds. An ‘immediate living’ that concerns the present in which the artist lives, but which always addresses the next person to whom the work is given.

Antonello: certainly childhood was a decisive period in my education.

I used to use a term, which I invented, to indicate a kind of state of grace that I perceived; this term was ‘Antonellare’. My name declined as a verb!

In here was my whole world, all the things that made me happy, games above all… but among the games there was one, drawing, which was the one that made me most serene and at the same time activated my imagination the most, giving me a kind of euphoria.

It wasn’t seeking refuge from a bad situation but rather finding yourself doing something that gave you happiness.

Over the years, the passion grew and changed in a thousand ways, but the attitude always remained the same.

P.d.A.: What studies have you done?

Santissimi: Sara, Art School and Academy of Fine Arts, painting section.

Antonello, Liceo Artistico, Architecture and Industrial Design.

P.d’A.: Were there any important encounters during your training?

Santissimi: Philosophy has been very formative, in the sense that it has provided inspiration for many of our works. We do not have a philosophical background, but we have realised that our work always starts with a conversation between us, a continuous talking to each other that by dint of talking reaches a material encounter in which reality seems to be accessible, conceptually tangible and paradoxically representable. Our works always arise from this encounter of forms that have dialogued before and that probably continue to dialogue whenever someone observes them.

P.d.A.: When did you start working together?

Santissimi: We started in 2005 making a contemporary art hotel in Sardinia, at that time we were Antonello Serra and Sara Renzetti.

In 2009, our first work ‘Settimo Cielo’ was born, and from there our research became Santissimi.

P.d’A.: What united you on an artistic level?

Santissimi: We are united on a human level, art comes as a consequence and immediately afterwards.

P.d’A.. : The idea of using the human body, playing on its brutal physicality and the scandal caused by nudity or showing its entrails or even its faeces, has illustrious predecessors in the history of recent art. Ron Mueck, Damen Hirst, who has never made a secret of wanting to do the same thing he did by dissecting a horse corpse with a human body, only complaining that he could not find one available, or Jenny Saville, and the Chapman brothers to name but a few… How does your work differ from that of these artists?

Santissimi: We have never made a scandal and are not interested in describing how our work differs from the work of the artists mentioned. The question presupposes a comparison, and any comparison between two similar or totally different things presupposes a previously established result.

The artist’s work has to be absorbed and for that it takes time, it has to be deepened and for that it takes time, it has to be freed from confrontation and for that it takes love, exactly what we should do with ourselves to love ourselves: free ourselves from confrontation with others.

We very much appreciate the work of Ron Mueck, Damien Hirst, Janny Saville and the Chapman brothers, but not because they exploit physical brutality, let alone scandal, but because they show a part of reality that is not exhibited, a reality that exists but is avoided. If this produces scandal, it is because our living together is based on a willingness to ignore rather than to understand. Scandal always arises from what exists but is momentarily excluded.

If the ugly causes scandal it is only because at a given moment or in a given circumstance the beautiful dominates, nothing more than this simple consideration.

We have always used the body to represent man in absolute, absolute in the sense of its stable value, without any reference to the everyday, or to the variables present in the everyday, and in this we feel totally different from the artists of the hyperrealist scene who instead seek to represent precisely this variable, this instability.

Our bodies are naked simply because the concept of man is naked, man is naked and not clothed.

We have never been associated with a sculptor like Michelangelo, who equally represented the naked man, this is because we often confuse the technique and material used with the ethics and aesthetics of the work. We rely too much on impact and this is part of the surface, the so-called superficiality.

P.d’A.: Does the idea of staging interest you? I wanted to ask you to explain your idea of site-specific work linked for example to the work you did in the former slaughterhouse in Cagliari ?

Santissimi: The idea of staging is of great interest to us because we have always been involved in the staging of our exhibitions, curating them directly on many occasions. In the case of the solo exhibition at the Exmà in Cagliari, we thought of the exhibition as an immersion in our way of thinking: many carnal bodies that were exposed to view as symbols in which to be reflected, as signs in which to exercise thought, as images (of) what escapes.

The exhibition developed both in the inner hall and along the outer façade.

The route in the inner room began with a strong bodily overbearingness in which the sculptures, even if filtered, dissected or migrated, were still clearly recognisable, only to end in the vague memory of the shapeless mass that at the end of the route forced one to look inside rather than outside.

A large mass of flesh choked by a rope came down from the ceiling surrounded by 120 flies fluttering in the air which, silent as so many stars in the sky can be, ended the pilgrimage with a simple indication: something has just gone and transformed into something else. It was the end of a journey in which we had spent so much time erasing our eyes, our hands, our legs, our arms, our feet, our whole body, to find ourselves in the simplest, most essential forms and among the largest, most open spaces.

As for the outside work, entitled ‘Rosa Rosae… “a man can kill one flower, two flowers, three… but cannot contain spring” displayed along the façade of the exma, was our first urban intervention.

The Exma was a slaughterhouse until 1966. The place and its history stimulated a vision in us: we imagined the structure as a holding tank into which, pressed and contained, the meat pours, coming out through the only way out, the arches of the façade.

We also thought of this work as an intervention on the city, which could bring and involve as many people as possible, stimulate reflection and colour the whole street with spring.

P.d.A.: Have you ever encountered the special effect as an end in itself that quickly exhausts the initial charge of amazement at its manufacture and stays there?

Santissimi: It has happened to us to receive it as consideration or criticism but we prefer to avoid it.

P.d’A.: Is there room for irony and transcendence in your work?

Santissimi: Of course, irony is part of the drama, there is no irony without pain.

The same goes for transcendence, all works go beyond reality, they are never where you look at them, where you are, they are always simultaneously here and there and not only there.

P.d’A.: When you start a work do you already have a clear idea of how it will develop, what space does the unexpected have in what you do?

Santissimi: We have a clear idea of what we want to achieve even if it is always contradicted each time. By now we have established that the idea is always just a draft of the final result.

P.d’A.: What kind of dialogue do you seek with the spectator who is in front of your work?

Santissimi: A silent dialogue. Lots of images and few words, also because the words that we ourselves use to accompany the works are trampolines where the image jumps, in the sense that it goes up and down like a child who lifts himself off the ground for fun to fall back onto his starting point. The same goes for sculptures, that jump is always there and that is where our research must be grasped, it must be taken on the fly, without stopping at the image, without stopping at the representation because everything is perpetually in motion, jumped precisely.

We do not demand anything from the spectator, we do not demand that this ‘leap’ be clear and understood, but we know that what I see, others also see. In each of us everything is already understood, in each of us the other is also understood, and it is here, only here, that our trust and our dialogue with the spectator is founded.

P.d.A.: Does the idea of the political body have any importance for you?

Santissimi: Yes, the political body as a religious body, as the body of the other, as the body of all, as the body of the you, the I and the we is fundamental.

Body understood as property, as defined and definable matter and political understood as organisation, activity and exercise is practically coincident with our work.

Ultimately, there is no better way to describe our work: organised matter of a body in exercise.

P.d’A.: In your opinion, does the sacred still have an importance in contemporary art?

Santissimi: Absolutely yes.

P.d’A.: What happens to works of art when there is no one to observe them, can the existence of a work of art be independent of the presence of an observer?

Santissimi: Quantum physics would tell you no. We tell you yes, they exist regardless as anything exists, but to this we add nothing more than a yes. A multiple yes because it is to be read both as an adverb and as a reflexive pronoun, where ‘yes’ affirms what the subject determines, and ‘is affirmed’ what the subject determines.

P.d’A.: Some artists are completely inside their work, others are obsessively dominated by it . . Where do you as artists stand in relation to your work?

Santissimi: Obsessively side by side.

The Santissimi, a duo made up of Sara Renzetti and Antonello Serra, both born in Sardinia, studied in Florence, academy of fine arts she (painting section) and architecture he (specialising in industrial design). They have no sculptural training, they learnt, in the open field of experience, to use the processes and methods of working with silicone so that it could make their imaginations visible.

Having never made up their minds, they began working together in 2009 and still renew this choice as long as their visions continue to coincide. “We started working without asking ourselves what we wanted to do. The works are visions and each work is a successive step of the previous work. No intention, no formalism, no casuistry, no style…”

They define their works as possible figures of excess, exercises of the mind, visual poems, walkable selfies on the transience of existence.

IN VIVO (F1-M1):

In Vivo dal latino nel vivente. Locuzione usata per indicare fenomeni biologici riprodotti in un organismo vivente.

Media: scultura in silicone, plexiglass, materiali vari.

Misure: 197 x 76 x 47 cm

Anno: 2013

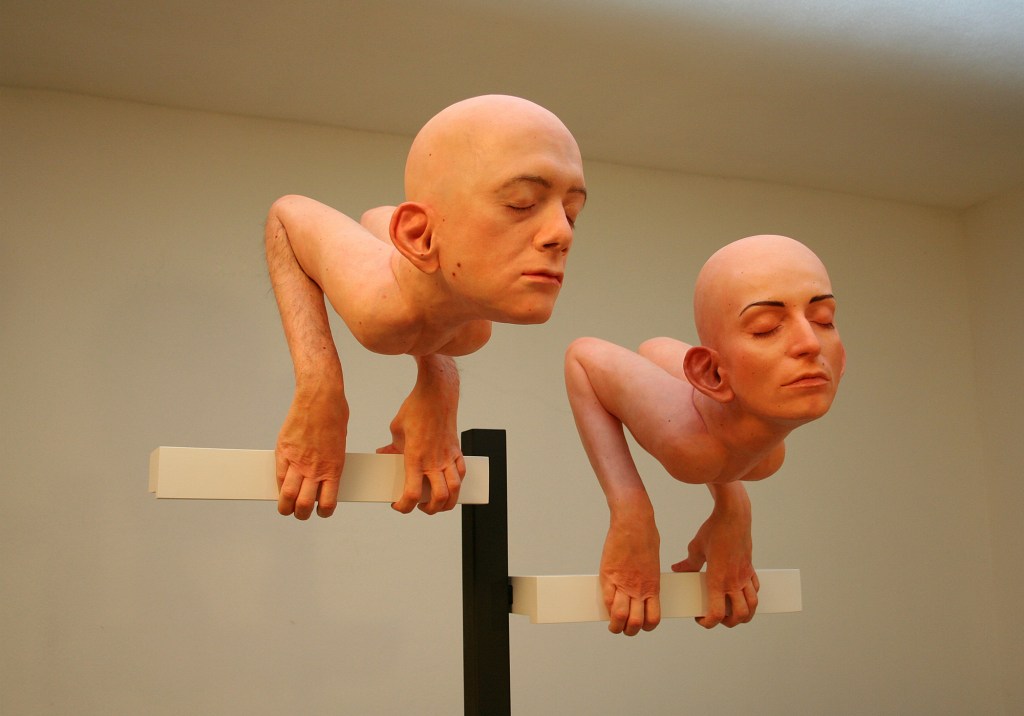

EPAVE 35° 29’ 54’’N 12° 36’ 18’’E

Nel mare.

L’acqua dell’acqua, estesa e libera, nell’aria piove.

Piante gocce e valanghe.

Croce di me sovente espatrio.

Fiume il corpo, ondoso transita, in oceanico strazio, il moto al divenire

Ove la prua è la poppa.

Montagna di me sotto i metri acquosi sgorgano

Mi obelisco in sella al ponte e cado cavallo.

Io finisco

Resto

Media: scultura in silicone, legno laccato bianco.

Misure: 185 x 77 x 31 cm

Anno: 2015

MIGRANTS Self – Portrait

Viandanti, fedeli alla maniera degli umani uomini, celebrano l’esilio dalla costanza e dal principio d’ identità.

Il desiderio di transire, la gioia al cospetto dell’esser ridotti a mirar il terminale incerto.

Bandita la fierezza e la fedeltà, si trasuda una nuova dimensione della coscienza che, nel corpo stesso, oramai bestemmiato, bocheggia l’epopea di una nuova esistenza.

Siamo nella transumanza.

Autunno e primavera

Genti, mandrie e pastori

Media: scultura in silicone, legno, ferro.

Misure: 180 x 80 x 48 cm

Anno: 2015

HORROR VACUI:

Media: scultura in silicone inglobata in quattro blocchi di resina.

Misure: 86 x 47 x 35 cm

Anno: 2012

MOM:

Se solo avessi compreso di quanto amore

avrei potuto negarti.

Standoti piano e poi forte,

come foglia al manto.

Immensamente fragile

Mamma

Media: scultura in silicone, corda.

Misure: 185 x 140 x 120 cm

Anno: 2016

NATURAL HISTORY (Ambra 1)

Commemorazione fossile.

Breve discorso sulla morte.

Media: scultura in silicone, resina.

Misure: 20 x 15 x 37 cm

Anno: 2011

MOSCHE in volo

Brando T. “Curiosamente, durante una nostra pausa pranzo, eravamo fermi davanti un bar quando abbiamo notato un’innumerevole serie di mosche che ci hanno letteralmente circondato. Spostando la posizione inoltre nulla sembrava mutare: la presenza di questi insetti era notevole e abbiamo deciso di chiedere a qualche abitante della zona maggiori informazioni al riguardo… L’ho notato dopo qualche giorno dalla prima forte scossa, sinceramente all’inizio non ci facevo caso ma devo dire che le mosche stanno diventando sempre più fastidiose e a volte siamo costretti a dover usare diversi veleni”.

(Il titolo dell opera è stato estrapolato da un commento su un blog che raccontava il terremoto in Abruzzo del 2009)

Media: 250 mosche in silicone, filo di rame e polipropilene.

Misure: singola mosca 1 x 0,7 x 0,6 cm; installazione variabile.

Anno: 2018

CORPUS

L’opera è stata realizzata nel periodo che va dall’autunno del 2020 a tutto l’inverno del 2021.

Ha richiesto un lungo periodo di ricerca sugli aspetti tecnici soprattutto riguardo la tenuta all’aria del silicone e il mantenimento della forma.

Installata dal 05 al 31 Maggio 2021 all’interno di una rimessa agricola, è stata concepita per non essere visitata dal pubblico, esattamente come nello stesso periodo si asteneva all’incontro tutto il resto del mondo.

L’ impossibilità di essere condivisa, tutta questa profonda solitudine, ci sembrava talmente intensa e sincera che subito dopo averla installata e aver realizzato foto e video noi stessi ce ne siamo privati ritornando da lei solo l’ultimo giorno per smontarla e imballarla.

Tutti quei giorni in cui lei stava lì e noi lontani, ci hanno permesso di capire meglio il motivo per il quale abbiamo fatto questo. Un motivo che ognuno di noi può ritrovare quando chiude gli occhi per dormire nonostante la vita o quando decide per la privazione nonostante il tutto.

Esattamente come sono i pensieri nonostante il corpo.

Media: Sculture sgonfiabile, silicone, aria, materiali vari.

Misure: 17×7,5x 4 metri

Anno: 2020/21

Antonello Serra e Sara Renzetti