(Scroll down for English version)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #gianlucabrando

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Gianluca, per la maggior parte degli artisti l’infanzia rappresenta l’età dell’oro, quella in cui cominciano a manifestarsi i primi “sintomi” di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Gianluca Brando: C’è un episodio dell’infanzia che mi è rimasto particolarmente impresso. Avevo circa quattro anni e all’asilo la maestra mise tra le mie mani un materiale che si imprimeva al contatto: era una sensazione mai provata prima di allora. Questo è uno dei primissimi ricordi che ho in assoluto, ma nella mia infanzia si manifestava anche una grande propensione al disegno. Da bambino amavo disegnare e primeggiavo per le mie abilità nella rappresentazione, mentre evitavo volentieri l’uso del colore.

P.d’A.: Quale è stata la tua formazione e che incontri importanti hai avuto in questi anni?

G.B.: Credo che per un artista la formazione sia qualcosa di continuo che segue la propria evoluzione. In questo percorso in divenire è possibile però rintracciare dei momenti decisivi. Per me è stato fondamentale un primo incontro al liceo con un docente artista outsider che ha potenziato molto le mie attitudini. Grazie a lui ho sviluppato precocemente la consapevolezza di essere sulla giusta strada; ho sentito che c’era qualcosa di grandioso che andava esplorato. Poi però, ad un certo punto, è stato necessario compiere il cosiddetto “delitto simbolico”, prendere le distanze e cominciare a fare le mie scelte.

Da Maratea – quindi da una Basilicata percepita come regione invisibile e marginale – sono partito per frequentare prima l’Accademia di Roma e in seguito quella di Venezia, per poi spostarmi a Taipei, dove ho vissuto per circa tre anni sviluppando il mio lavoro nel contesto di studi condivisi. Taiwan è stata la mia base anche per scoprire alcune zone della Cina e del Giappone per poi fare ritorno in Italia, tra Torino e Milano, che è la città in cui vivo da qualche anno. La mia formazione è passata attraverso tutti questi luoghi.

P.d’A.: Che cosa hanno lasciato questi luoghi nel tuo lavoro?

G.B.: Non credo che spetti a me decifrarlo più di quanto non suggerisca l’osservazione stessa del mio lavoro.

Il paesaggio della mia infanzia e adolescenza proponeva sempre due orizzonti intercambiabili; da una parte la montagna e dall’altra il mare. Bastava girarsi, ruotare su se stessi per vedere l’una o l’altra cosa.

Credo che il contatto con i luoghi ci forma in un determinato modo perché ognuno di essi offre esperienze peculiari e soprattutto non virtuali.

Sono aspetti su cui ultimamente mi capita di riflettere, soprattutto perché il contatto diretto con le cose che incontro nel percorso quotidiano ha per me un ruolo primario. Aver avuto a che fare con luoghi così distanti tra loro credo che abbia influito molto in questa direzione.

P.d’A.: Ti chiederei di parlare più diffusamente del modo in cui il contatto quotidiano con le cose ha un ruolo primario per te.

G.B.: La mia attitudine è simile a quella di un esploratore che incontra inaspettatamente qualcosa che lo attrae nel suo cammino, magari proprio nel momento in cui non stava cercando niente di particolare. Per me incontrare una forma vuol dire entrare in ascolto e in simbiosi con essa. Le forme che incontro sono già cariche di storie e avvenimenti: una preesistenza che non dipende dal mio fare. Entrare in contatto con loro ed esaltarne anche le fragilità mi permette di portare alla luce quello che sono e quello che non sono. Questo contatto con le cose non è soltanto un’azione mediata dal toccare, ma è soprattutto un’azione di ascolto il cui risultato consiste, sostanzialmente, in un ribaltamento di prospettive.

Riconoscere sulla spiaggia il cestello di una lavatrice riformato dalle onde del mare, oppure constatare la ripetitività con cui riappare, a bordo strada, la stessa parte di carrozzeria o, ancora, essere attratti dalla forma metamorfica di un fungo a tremila metri di altitudine, oppure rivedere piccoli gusci di lumaca in attesa sulle superfici della propria casa… Sono soltanto alcuni esempi di quei particolari momenti di connessione che mi piace definire “prese di contatto”; momenti originari che hanno anche un “valore politico”.

P.d’A.: Mi sembra, leggendo quello che scrivi, che si possa parlare anche di valore poetico. Per te poesia e politica possono dialogare?

G.B.: Ho messo tra virgolette “valore politico” proprio per indicarne l’accezione più ampia ed estesa del termine; avrei potuto dire anche “valore poetico”.

Per me poetico e politico stanno insieme. Un gesto poetico è anche un gesto politico nel senso più alto. È attenzione e dedizione totale a ciò che sembra insignificante o marginale.

P.d’A.: Che importanza ha per te l’idea del frammento?

G.B.: Il frammento come “particella”, residuo di un organismo o di un simbolo più ampio è qualcosa di molto vitale perché è una condizione trasformativa che dà spazio a una rilettura stratificata capace di incuriosire e sviluppare l’immaginazione.

Un frammento di meteorite sulla terra è il segno di qualcosa di altro che sta lontanissimo da noi, in uno spazio ancora sconosciuto: un segno che ci rende consapevoli del limite della condizione umana, ma che, al tempo stesso, può farci proiettare più in là.

P.d’A.: Ti volevo chiedere ora di parlare del disegno e dell’importanza che ha in quello che fai?

G.B.: Il disegno è un mezzo di alimentazione per quello che poi faccio nello spazio fisico. Ha una sua autonomia, ma può essere anche chiarificatore nella sua capacità di tradurre pensieri in immagini. È un inizio che per me ha la sua magia nel momento stesso della sua realizzazione. Un momento di fragile libertà.

P.d’A.: Ti volevo chiedere di parlare di “Soffio (passaruota)”.

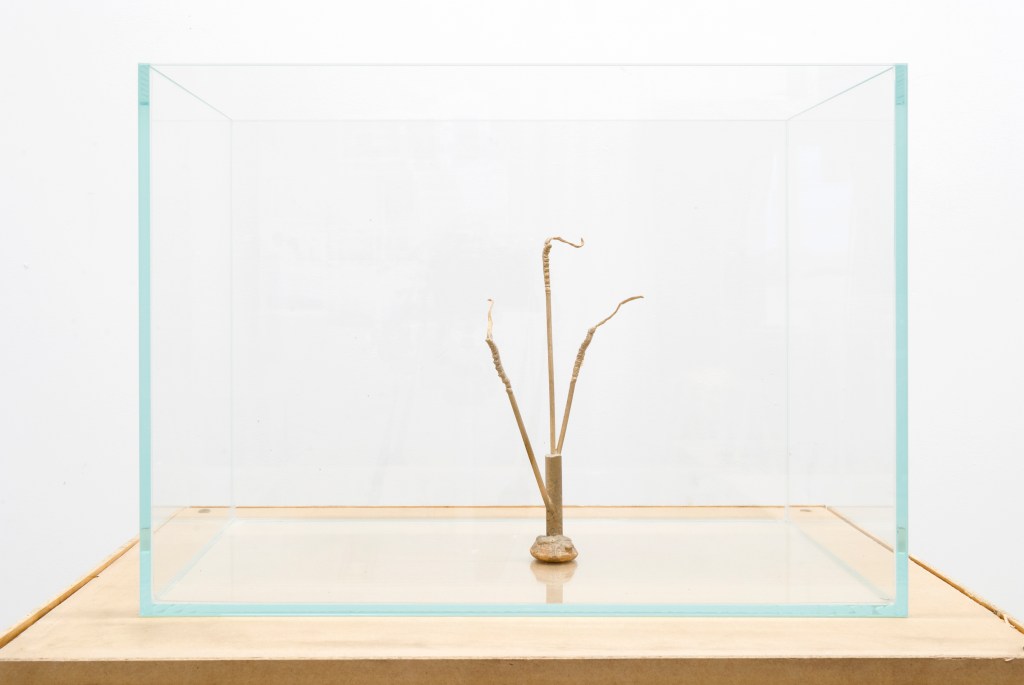

G.B.: Su diversi percorsi stradali ho iniziato a notare il ripetersi della stessa parte di carrozzeria che giaceva abbandonata a bordo strada. Sempre la stessa parte, ma sempre differente. Una vera disseminazione di frammenti dalla comune origine che ho iniziato a raccogliere.

La mia azione consiste nel trattare ciascun singolo frammento come una matrice seriale in grado di generare una forma unica. Un ribaltamento di opposti che, partendo dall’immaginario comune dell’automobile come emblema della serialità, di uno standard pervasivo, restituisce una forma di primitività.

P.d’A.: Come mai associ l’idea di soffio a queste sculture?

G.B.: La ricerca di un titolo per me non è semplicemente legata all’associare un’idea a una forma.

Il titolo è un nome che accompagna il lavoro, quindi dovrebbe offrire allo spettatore uno spunto, un indizio per accedere a un panorama ampio, stratificato, ma anche ambivalente, senza imporre una sola e dogmatica lettura ma, al contrario, aprendo degli interrogativi.

Un soffio di vento può cambiare repentinamente l’aspetto, l’anima stessa di una forma: è un istante in cui qualcosa di certo cambia stato, si ribalta nel suo contrario o si stacca per prendere il volo. Vive, muore, si rigenera.

P.d’A.: Ti interessa l’idea di leggerezza?

G.B.: Posso chiederti che cosa intendi più precisamente per “idea di leggerezza”?

P.d’A.: Leggerezza per me è la capacità di sottrarre peso all’esistenza attraverso piccoli atti sovversivi, invisibili ai più, che richiedono una prassi quotidiana ed una dedizione totale .

G.B.: Mi sembra una bellissima riflessione da lasciare a chi ha avuto voglia di leggerci fino a qui.

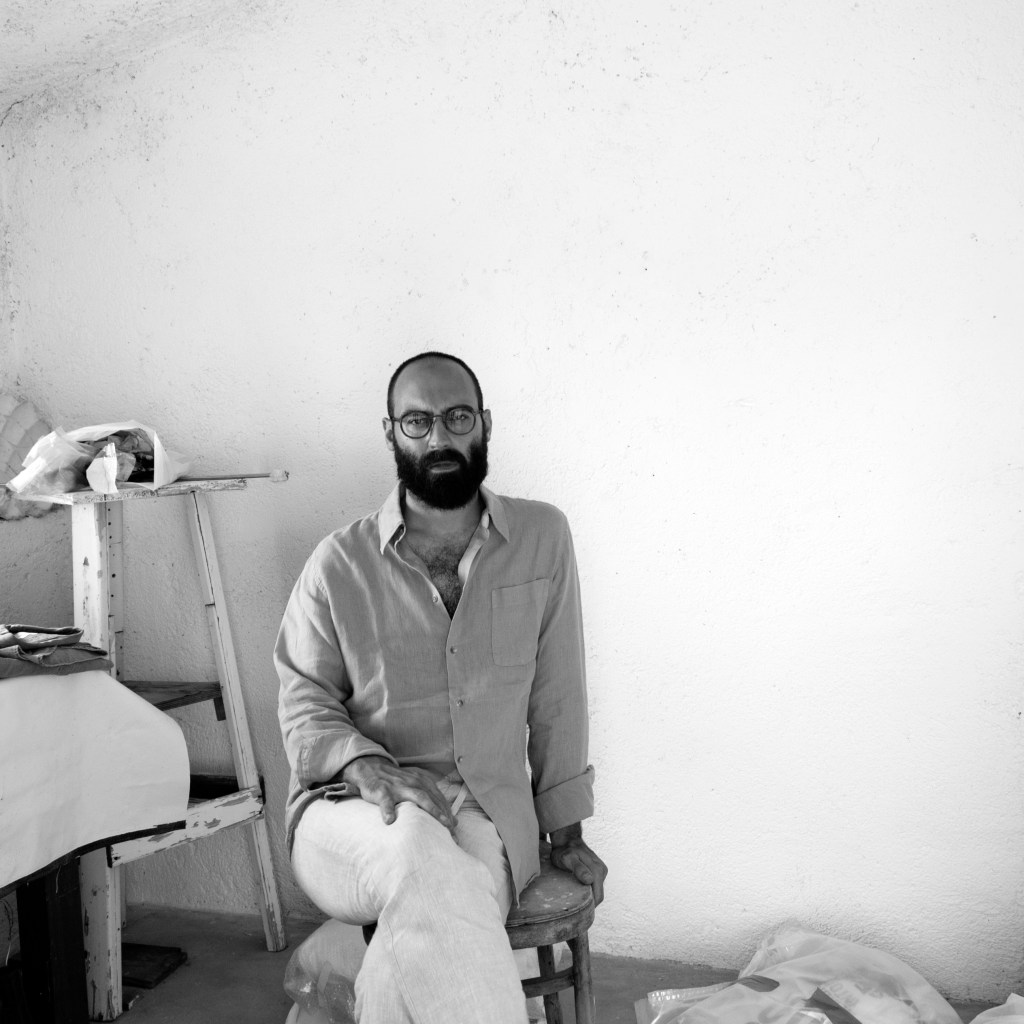

Gianluca Brando (Maratea, 1990), vive e lavora a Milano. Ha studiato nelle Accademie di Belle Arti di Roma e di Venezia. Dal 2014 al 2017 ha vissuto a Taipei, Taiwan, dove ha sviluppato il suo lavoro nel contesto di alcuni programmi di residenza artistica per poi trascorrere un periodo di ricerca in Cina. Al rientro in Italia, tra 2018 e 2019, è stato artista in residenza presso Cripta 747 a Torino, Viafarini e Officine Saffi a Milano.

Negli ultimi anni il suo lavoro è stato presentato da spazi indipendenti e istituzioni, tra i quali: Mattatoio, Roma (2023); MAXXI, Roma (2023); Spazio Taverna, Roma (2022, 2021); Riss(e), Varese (2022); Fondazione Francesco Fabbri, Pieve di Soligo (2021), Fondazione Pini, Milano (2020); Fondazione SoutHeritage, Matera (2020); Viafarini, Milano (2019); Cripta 747, Torino (2018); Officine Saffi, Milano (2018).

È risultato finalista in diversi premi, tra i quali: Talent Prize (edizioni 2023 e 2021), Premio Conai (2022), Premio Fabbri (edizioni 2020, 2017, 2015).

English text

Interview to Gianluca Brando

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistinterview #gianlucabrando

Parola d’Artista: Hi Gianluca, for most artists childhood represents the golden age, the one in which the first ‘symptoms’ of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Gianluca Brando: There is an episode from my childhood that has particularly stayed with me. I was about four years old and in kindergarten the teacher placed a material in my hands that was imprinted on contact: it was a sensation I had never experienced before. This is one of the very first memories I have, but in my childhood there was also a great propensity for drawing. As a child, I loved to draw and excelled in my representational skills, while I willingly avoided the use of colour.

P.d’A.: What was your training and what important encounters have you had over these years?

G.B.: I believe that for an artist, training is something continuous that follows one’s own evolution. In this evolving path, however, it is possible to trace some decisive moments. For me, an initial encounter in high school with an outsider artist teacher who greatly enhanced my aptitudes was fundamental. Thanks to him, I developed an early awareness that I was on the right path; I felt that there was something great that needed to be explored. But then, at a certain point, it was necessary to carry out the so-called ‘symbolic crime’, to distance myself and start making my own choices.

From Maratea – thus from a Basilicata perceived as an invisible and marginal region – I left to attend first the Academy in Rome and then that in Venice, and then moved to Taipei, where I lived for about three years developing my work in the context of shared studies. Taiwan was also my base for discovering some parts of China and Japan and then returning to Italy, between Turin and Milan, which is the city where I have been living for the past few years. My education passed through all these places.

P.d’A.: What have these places left behind in your work?

G.B.: I don’t think it is up to me to decipher it any more than the very observation of my work suggests.

The landscape of my childhood and adolescence always proposed two interchangeable horizons; on one side the mountain and on the other the sea. All you had to do was turn around, rotate on yourself to see one or the other.

I believe that contact with places shapes us in a certain way because each one offers peculiar and above all non-virtual experiences.

These are aspects that I have been reflecting on lately, especially because direct contact with the things I encounter on my daily path plays a primary role for me. Having had to deal with places so distant from each other I think has had a great influence in this direction.

P.d’A.: I would ask you to talk more about the way in which daily contact with things plays a primary role for you.

G.B.: My attitude is similar to that of an explorer who unexpectedly encounters something that attracts him on his path, perhaps at the very moment when he was not looking for anything in particular. For me, encountering a form means going into listening and symbiosis with it. The forms I encounter are already loaded with stories and events: a pre-existence that does not depend on my doing. Coming into contact with them and bringing out even their fragilities allows me to bring to light what they are and what they are not. This contact with things is not only an action mediated by touching, but is above all an action of listening, the result of which consists, essentially, in a reversal of perspectives.

To recognise on the beach the basket of a washing machine reformed by the waves of the sea, or to note the repetitiveness with which the same part of the bodywork reappears on the side of the road, or to be attracted by the metamorphic form of a mushroom at an altitude of three thousand metres, or to see small snail shells waiting on the surfaces of one’s home… These are just a few examples of those particular moments of connection that I like to call ‘contact points’; original moments that also have a ‘political value’.

P.d.A.: It seems to me, reading what you write, that we can also talk about poetic value. For you, can poetry and politics dialogue?

G.B.: I put ‘political value’ in inverted commas precisely to indicate the broadest and most extensive meaning of the term; I could also have said ‘poetic value’.

For me poetic and political go together. A poetic gesture is also a political gesture in the highest sense. It is attention and total dedication to what seems insignificant or marginal.

P.d’A.: What importance does the idea of the fragment have for you?

G.B.: The fragment as a ‘particle’, a remnant of an organism or a larger symbol is something very vital because it is a transformative condition that gives room for a layered reinterpretation capable of intriguing and developing the imagination. A fragment of a meteorite on earth is a sign of something else that is far away from us, in a space that is still unknown: a sign that makes us aware of the limit of the human condition, but at the same time can make us project ourselves further.

P.d’A.: I wanted to ask you now about drawing and the importance it has in what you do?

G.B.: Drawing is a means of feeding what I then do in physical space. It has its own autonomy, but it can also be clarifying in its ability to translate thoughts into images. It is a beginning that for me has its magic in the very moment of its realisation. A moment of fragile freedom.

P.d’A.: I wanted to ask you about “Soffio (wheel arch)”.

G.B.: On different road trips, I started noticing the repetition of the same body part lying abandoned by the roadside. Always the same part, but always different. A real dissemination of fragments with a common origin that I started to collect. My action consists of treating each individual fragment as a serial matrix capable of generating a unique form. An overturning of opposites that, starting from the common imagery of the automobile as an emblem of seriality, of a pervasive standard, returns a form of primitiveness.

P.d’A.: How come you associate the idea of breath with these sculptures?

G.B.: The search for a title for me is not simply about associating an idea with a form. The title is a name that accompanies the work, so it should offer the viewer a cue, a clue to access a broad, layered, but also ambivalent panorama, without imposing a single, dogmatic reading but, on the contrary, opening up questions.

A gust of wind can abruptly change the appearance, the very soul of a form: it is an instant in which something certainly changes state, reverses into its opposite or detaches itself to take flight. It lives, it dies, it regenerates.

P.d’A.: Are you interested in the idea of lightness?

G.B.: May I ask you what you mean more precisely by ‘idea of lightness’?

P.d’A.: Lightness for me is the ability to subtract weight from existence through small subversive acts, invisible to most, that require daily practice and total dedication.

G.B.: It seems to me a beautiful reflection to leave to those who have been willing to read us so far.

Gianluca Brando (Maratea, 1990) lives and works in Milan. He studied at the Academies of Fine Arts in Rome and Venice. From 2014 to 2017, he lived in Taipei, Taiwan, where he developed his work in the context of some artistic residency programmes and then spent a period of research in China. Upon his return to Italy, between 2018 and 2019, he was artist-in-residence at Cripta 747 in Turin, Viafarini and Officine Saffi in Milan.

In recent years, his work has been presented by independent spaces and institutions, including: Mattatoio, Rome (2023); MAXXI, Rome (2023); Spazio Taverna, Rome (2022, 2021); Riss(e), Varese (2022); Fondazione Francesco Fabbri, Pieve di Soligo (2021), Fondazione Pini, Milan (2020); Fondazione SoutHeritage, Matera (2020); Viafarini, Milan (2019); Cripta 747, Turin (2018); Officine Saffi, Milan (2018).

He was a finalist in several awards, including: Talent Prize (editions 2023 and 2021), Premio Conai (2022), Premio Fabbri (editions 2020, 2017, 2015).