(▼scroll down for English version)

#paroladartista #nero #black #marcoacquafredda

Parola d’Artista: Tutti gli artisti, o almeno credo, fanno prima o poi i conti con il nero, e tu?

Marco Acquadredda: Non mi sono mai chiesto se tutti gli artisti fanno i conti con il nero, ma c’è, ed è vero, chi ha un rapporto privilegiato con questo colore. Personalmente ho sempre dialogato con naturalezza con questo “medium”, che ciclicamente ritorna nella mia ricerca artistica. Il nero ha per me uno stretto legame con il senso della scrittura: scrivere nero su bianco è la volontà di essere chiari, procedere nella scrittura porta di per sé, come atto, il senso della narrazione. Non mi piace l’accezione “grafica dell’uso del nero, mentre mi piace l’idea che il colore sia l’assenza di luce e allo stesso tempo, di contro, la somma per mescolanza di tutti i colori. Chi ha paura del buio intende bene il disagio dell’ignoto e l’assenza della percezione a cui affidiamo maggior rilevanza, ma ricordo che l’oscurità è anche il rifugio nel grembo materno, momento sicuro e “creativo” per eccellenza. Mi rimase molto impresso, anni fa, quando mi fu detto che il nero in molte tecniche non viene utilizzato a causa del valore cromatico che male si accorda con le altre cromie. Il nero è stato nella mia ricerca, finora, una traccia visibile che cerca il suo posto in uno spazio, talvolta come unità minima, talvolta occupandolo interamente, e di certo il suo utilizzo, in senso elitario, semplifica praticamente la realizzazione di un lavoro. “Maneggiare ombre” è invece un mio lavoro recente, l’ultimo di una serie di mie indagini ancora in divenire a cui sto lavorando da alcuni mesi. Il mio tentativo, in questo mio “nero” è la pratica, forse “maniacale”, con la quale tento di descrivere fisicamente il comportamento della luce, quindi dell’ombra, su di una superficie reale. Descrivere un processo creativo è cosa complessa, capita talune volte di partire da suggestioni o idee, altre volte con bisogni o urgenze tanto intime o profonde da poterle intuire e forse solo in parte al termine del lavoro stesso. La visione di alcuni disegni di Seurat mi ha fatto da innesco: la descrizione di figure e paesaggi per masse di ombra e luce mi ha restituito una forte sensazione, è la trama della carta che fa vibrare i segni che compongono queste apparenti semplici composizioni. Non è stata mia intenzione copiarne il lavoro, direi che dopo questo incontro, come in un dialogo, dovessi rispondere a Seurat, a modo mio. Cercando relazioni diversa con lo spazio del disegno era già da un po’ che mi cimentavo con dei rapidograph, penne a china risalenti agli anni’90, ritrovati casualmente in un fondo di magazzino con i quali ho ricoperto oggetti naturali (noci e altri piccoli oggetti) seguendo le asperità della loro “pelle”, cercando di descrivere su di essi, fisicamente, il comportamento di un’ombra, quindi annerendo alcune parti di esse o totalmente secondo il criterio del momento, ripercorrendo i piccoli e angusti spazi reali. Sentivo di dover procedere oltre, ed è così che il ritrovamento di certe mappe europee, acqueforti della fine del ‘600, sono state il palcoscenico di un ulteriore luogo su cui intervenire. In questo nuovo contesto, allo spazio e alla luce si è aggiunto il concetto di tempo, dato che con segni ripetuti ho riempito, come nel gioco “annerire i puntini”, ogni riferimento scritto, cancellando la memoria e consegnando all’oblio il lavoro tracciato da ignoti incisori dell’epoca, ora dopo ora, giorno dopo giorno, settimana dopo settimana. Le mappe sono state in parte così restituite alla natura facendo attenzione a lasciare i monti, le strade, le città, i laghi e i fiumi… le carte, oramai mute, sono adesso suscettibili a nuove interpretazioni passando da visioni aeree a notturni di fitte ragnatele e cieli stellati. Terminate le carte gli elementi naturali descritti in precedenza (guscio di tartaruga, chiocciole, legni con incrostazioni di balani, ossa di tasso e altro) sono stati poggiati su di esse creando così un cortocircuito tra reale disegnato: realtà e finzione si incontrano in una messa in scena dove tutto il mondo è ridisegnato e la composizione sembra fondersi e alla fine, ancora confondersi. Vorrei terminare questo racconto parafrasando la citazione di quello che è considerato il testamento spirituale di Hokusai, che nel colophon delle Cento vedute del Monte Fuji intende manifestare l’impossibilità umana nel poter tracciare e ridisegnare tutte le “cose” del mondo; solo adesso mi rendo conto, con tutta l’umiltà del caso, di aver ribadito con i miei “Notturni” il medesimo pensiero e con esso la meraviglia dal micro al macrocosmo di tutto quello che ci circonda.

English version

Marco Acquafrdda on black

#paroladartista #nero #black #marcoacquafredda

Parola d’Artista: All artists, or at least I think so, sooner or later come to terms with black, don’t you?

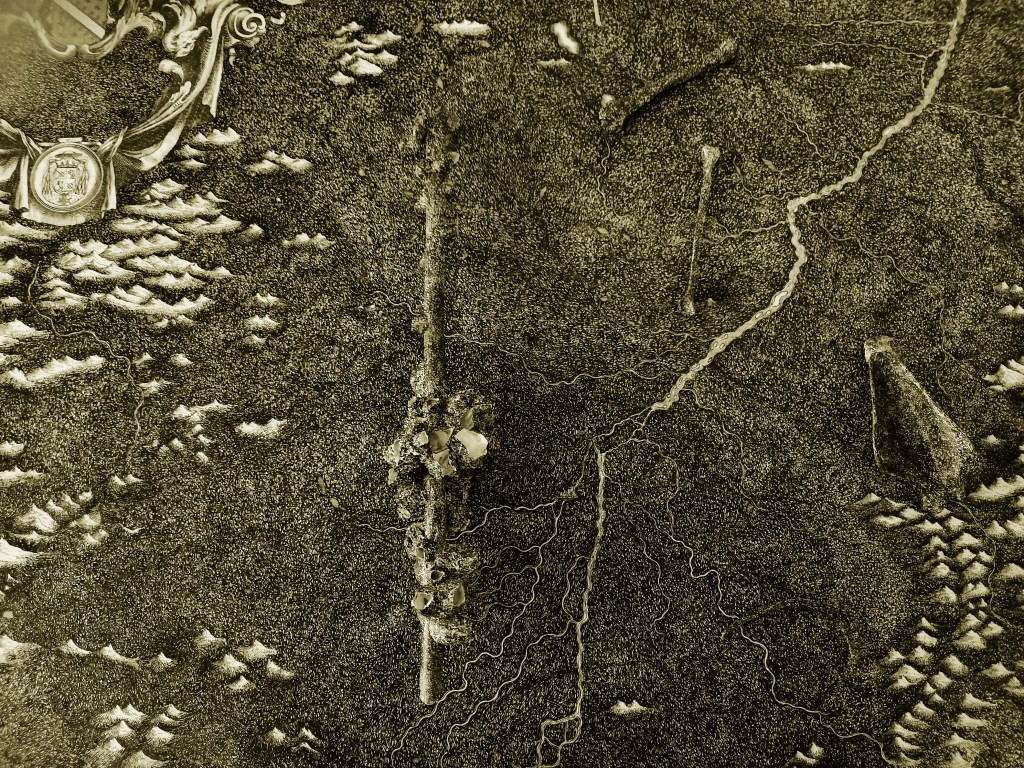

Marco Acquadredda: I have never asked myself whether all artists come to terms with black, but there are, and it is true, those who have a privileged relationship with this colour. Personally, I have always had a natural dialogue with this ‘medium’, which cyclically returns in my artistic research. For me, black has a close connection with the sense of writing: writing black on white is the will to be clear, to proceed in writing carries in itself, as an act, the sense of narration. I do not like the ‘graphic’ meaning of the use of black, while I like the idea that colour is the absence of light and at the same time, conversely, the sum by mixture of all colours. He who is afraid of the dark understands well the discomfort of the unknown and the absence of the perception to which we entrust most importance, but I remember that darkness is also the refuge in the womb, a safe and ‘creative’ moment par excellence. I was very impressed, years ago, when I was told that black is not used in many techniques because of the chromatic value that goes badly with other colours. In my research so far, black has been a visible trace that seeks its place in a space, sometimes as a minimal unit, sometimes occupying it entirely, and certainly its use, in an elitist sense, practically simplifies the realisation of a work. “Maneggiare ombre” (Handling shadows), on the other hand, is a recent work of mine, the latest in a series of my investigations that I have been working on for a few months now. My attempt, in this ‘blackness’ of mine, is the practice, perhaps ‘maniacal’, with which I attempt to physically describe the behaviour of light, hence shadow, on a real surface. Describing a creative process is a complex thing, it happens sometimes starting with suggestions or ideas, other times with needs or urgencies so intimate or profound that they can only be guessed at, and perhaps only in part at the end of the work itself. The vision of some of Seurat’s drawings acted as a trigger for me: the description of figures and landscapes by masses of shadow and light gave me a strong sensation, it is the texture of the paper that makes the signs that make up these seemingly simple compositions vibrate. It was not my intention to copy his work, I would say that after this encounter, as in a dialogue, I had to respond to Seurat, in my own way. Looking for a different relationship with the space of drawing, I had already been experimenting for a while with rapidographs, Indian ink pens dating back to the 1990s, casually found in a warehouse fund with which I covered natural objects (walnuts and other small objects) following the roughness of their ‘skin’, trying to describe on them, physically, the behaviour of a shadow, thus blackening some parts of them or totally according to the criterion of the moment, tracing the small and narrow real spaces. I felt I had to go further, and so it was that the discovery of certain European maps, etchings from the late 17th century, provided the stage for a further place on which to intervene. In this new context, the concept of time was added to space and light, as with repeated marks I filled in, as in the game “blacken the dots”, every written reference, erasing memory and consigning to oblivion the work traced by unknown engravers of the time, hour after hour, day after day, week after week. The maps were thus partly returned to nature, taking care to leave the mountains, roads, towns, lakes and rivers behind… the maps, now mute, are now susceptible to new interpretations, passing from aerial visions to nocturnal views of thick cobwebs and starry skies. Once the cards were finished, the natural elements described above (tortoise shells, snails, wood encrusted with baleen, badger bones and more) were placed on them, thus creating a short-circuit between drawn reality and fiction: reality and fiction meet in a mise-en-scene where the whole world is redrawn and the composition seems to merge and, in the end, still merge. I would like to end this story by paraphrasing the quotation from what is considered Hokusai’s spiritual testament, which in the colophon of the Hundred Views of Mount Fuji intends to manifest the human impossibility of being able to trace and redraw all the “things” of the world; only now do I realise, with all humility, that with my “Nocturnes” I have reiterated the same thought and with it the wonder from the micro to the macrocosm of everything that surrounds us.