(▼scroll down for English version)

#paroladartista #sacro #sacred #matteomontani

Parola d’Artista: secondo te il tema del sacro ha ancora una sua importanza nell’arte di oggi e nel mondo in cui viviamo?

Matteo Montani: Questa sul sacro è una bella domanda al giorno d’oggi, perché dal mio punto di vista conduce immediatamente a una condizione non esclusivamente individuale, come accade per tante questioni sulle pratiche artistiche. Il sacro nasce con la morte, così come l’arte è nata dalla morte, o per via della morte. Il concetto di sacro è inscindibile dal concetto di morte, dunque mettiamola come ci pare, tocca tutti. Non vado a argomentare le dichiarazioni di cui sopra, che mi sembrano evidenti, altrimenti si finirebbe per scrivere un saggio di antropologia e storia dell’arte! Torno al “tocca tutti” (o meglio ci tocca a tutti), e qui invece farò un’affermazione più arbitraria, meno argomentabile.

Se è vero che gran parte del concetto di sacro è per forza di cose associato al concetto di religione e benché, come da primo postulato, il sacro è il primordio poiché si affaccia sulla morte (e non ne è assolutamente né l’antidoto, né il contraltare), le religioni si sono poi ufficialmente fatte carico di interpretare questa innata “sacralità” che è propria della specie umana, sorgendo in modo spontaneo e fisiologico direi.

Di conseguenza, anche se, ripeto, questo non ha la presunzione (né ho un interesse particolare a che la cosa sia condivisa) di essere un postulato, di conseguenza, dicevo, l’idea è che in un modo o nell’altro siamo tutti religiosi. In definitiva c’è un aspetto di sacro in ognuno di noi, fosse anche solo questo sguardo che abbiamo sulla morte, dunque sulla vita!* Tutto poi si decide nella latenza o nella consapevolezza di questo sguardo. Penso che in generale, meno si ha paura più si riesce ad avere un rapporto col sacro e se si riesce a non avere paura o il meno paura possibile, nel nostro lavoro, si lavora con sacralità.

In seguito, c’è un’altra cosa da accennare rispetto al discorso del sacro. In primis c’è da escludere tutto il discorso di un’arte devozionale, e ok. Perché tu fai una bella domanda sul sacro e non sullo spirituale o sul trascendente o appunto, sul religioso. Questo va sottolineato in quanto la parola sacro associata alla parola arte rimanda per forza di cose a un concetto di arte sacra, che (io dico aimè) si è esaurita a livello ufficiale, ma ecco appunto che può essere rimesso in gioco dagli artisti stessi. Allora il sacro può diventare un atteggiamento nell’approccio al lavoro, il sacro-officio… Personalmente spesso associo il concetto di sacro a quello di trascendente. Quando Francois Julienne ** dice che il trascendente non è da un’altra parte chissà dove, ma è qui sempre in mezzo a noi e fa un lavoro silenzioso, incessante e umile per legare (dico io) il sacro alla vita, dice che tutto è intriso di trascendenza e dunque di sacralità. Poi specialmente nel nostro lavoro, il lavoro sull’immagine, la relazione col sacro e il trascendente è basilare. L’immagine (e dunque l’immaginazione) è tutto, specie poi quando si a che fare col sacro. Gli gnostici dicevano “la verità è giunta a noi in simboli e immagini” e poi si potrebbe continuare, passando per la “conversio ad phantasmata”” di Tommaso d’Aquino cioè tutto il rapporto con la similitudine e dunque l’immaginazione come ponte tra astratto e sensibile…

La cultura ufficiale materialista dominante in Occidente è concentrata in uno sforzo che non ha fatto passare come sarebbe dovuto e corretto, l’informazione che nei 50/60 anni a cavallo tra la fine del 1800 e gli inizi del ventesimo secolo, e specie agli inizi del XX secolo, c’è stato un vento spirituale importantissimo che ha coinvolto e influenzato profondamente tutti gli artisti di quella generazione e di conseguenza, inconsapevolmente, anche le generazioni successive, fino ad arrivare a noi. Leggendo il bel libro di Roberto Borghi Libri Aurei, (Lorenzelli Arte. 2017), si potrà avere una sorprendente rivelazione tangibile di quanto la cultura artistica della quale siamo figli sia stata influenzata, connessa e costituita da una rinascenza dello spirito oserei dire fondante.

Per rispondere conclusivamente alla tua domanda, penso che il tema del sacro sia determinante: se Rilke diceva “solo l’uomo è come rigirato su sé stesso…” *** per via della consapevolezza della morte, contrapponendo questo sguardo all’aperto dello sguardo animale. allora io credo che attraverso il sacro, e credo che Rilke questo lo sapesse bene, possiamo avere anche noi, come l’animale, uno sguardo sull’aperto, e il bello di questo sguardo è a mio avviso che si apre a una dimensione spazio-temporale indescrivibile perché è uno sguardo-spazio sulla vita e sulla morte contemporaneamente e mi piace immaginare questo spazio come l’accadimento che si produce nel momento in cui l’ultima nota di violino del quartetto dei tempi di Olivier Messiaen **** viene abbandonata dal pianoforte in un posto lontanissimo che sembra il confine dell’universo conosciuto. Ascoltandolo accade che quando percepiamo il suono fisicamente cessare, lo sentiamo continuare in uno spazio (lo stesso di quell’universo? parallelo?) dentro noi. Prima era fuori, poi dentro.

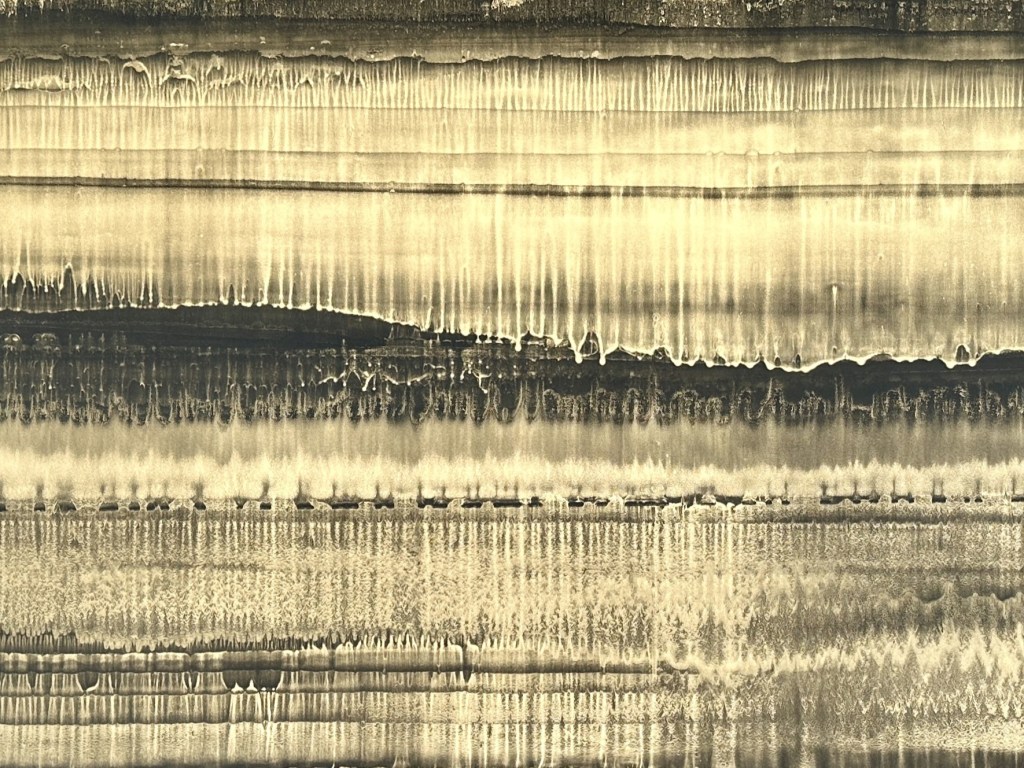

“Andare verso il giorno” è un titolo che ho scelto per una mia opera e che potrebbe funzionare per molte. Si tratta di una citazione di un detto degli antichi egizi che così consideravano il momento del trapasso dalla morte alla vita, no scusa ho sbagliato, dalla vita alla morte, o forse…

note:

* vedi François Cheng, Cinque Meditazioni sulla morte (ovvero sula vita), trad. di Chiara Tartarini, Bollati Boringhieri, 2015

** François Jullienne, Vivere di paesaggio, ovvero l’impensato della ragione, a cura di Francesco Marsciani, Mimesis 2017

*** R.M. Rilke, Elegie Duinesi, trad. di Enrico De Portu e Igea DE Portu, Einaudi, 1978

English version

Points of view on sacred Matteo Montani

#paroladartista #sacro #sacred #matteomontani

Parola d’Artista: In your opinion, does the theme of the sacred still have relevance in today’s art and the world we live in?

Matteo Montani: This question about the sacred is a good one nowadays, because from my point of view it immediately leads to a condition that is not exclusively individual, as is the case with so many questions about artistic practices. The sacred is born with death, just as art is born from death, or because of death. The concept of the sacred is inseparable from the concept of death, so let us put it as we like, it affects everyone. I am not going to argue the above statements, which seem obvious to me, otherwise one would end up writing an essay on anthropology and art history! I return to the ‘touches all’ (or rather touches us all), and here instead I will make a more arbitrary, less arguable statement.

While it is true that a large part of the concept of the sacred is necessarily associated with the concept of religion, and although, as per the first postulate, the sacred is the primordial as it faces death (and is absolutely neither its antidote nor its counterbalance), religions have then officially taken it upon themselves to interpret this innate ‘sacredness’ that is proper to the human species, arising in a spontaneous and physiological way I would say.

Consequently, although, I repeat, this does not presume (nor do I have any particular interest in it being shared) to be a postulate, consequently, as I was saying, the idea is that in one way or another we are all religious. Ultimately there is an aspect of the sacred in each of us, even if it is only this glimpse we have of death, therefore of life! Everything then is decided in the latency or awareness of this gaze. I think that in general, the less one is afraid, the more one is able to have a relationship with the sacred, and if one is able to have no fear or as little fear as possible, in our work, one works with sacredness.

Next, there is another thing to mention with respect to the discourse of the sacred. First of all, there is the entire discourse of a devotional art, and OK. Because you ask a good question about the sacred and not about the spiritual or the transcendent or indeed, the religious. This must be emphasised because the word sacred associated with the word art necessarily refers back to a concept of sacred art, which (I say aimlessly) has been exhausted at an official level, but here it can be brought back into play by the artists themselves. Then the sacred can become an attitude in the approach to work, the sacred-officio… Personally, I often associate the concept of the sacred with that of the transcendent. When Francois Julienne ** says that the transcendent is not somewhere else who knows where, but is always here among us and does silent, unceasing and humble work to link (I say) the sacred to life, he is saying that everything is imbued with transcendence and therefore sacredness. Then especially in our work, the work on the image, the relationship with the sacred and the transcendent is basic. The image (and therefore the imagination) is everything, especially when dealing with the sacred. The Gnostics said “the truth has come to us in symbols and images” and then we could continue, passing through the “conversio ad phantasmata”” of Thomas Aquinas, that is, the whole relationship with the simile and therefore the imagination as a bridge between the abstract and the sensible…

The official materialist culture dominant in the West is concentrated in a effort that has not passed on as it should and should have done, the information that in the 50/60 years between the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 20th century, and especially at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a very important spiritual wind that deeply involved and influenced all the artists of that generation and consequently, unconsciously, even the generations that followed, right up to us. Reading Roberto Borghi’s beautiful book Libri Aurei, (Lorenzelli Arte. 2017), one can have a surprising tangible revelation of how much the artistic culture of which we are the children has been influenced, connected and constituted by a renaissance of the spirit, dare I say it.

To answer your question conclusively, I think the theme of the sacred is decisive: if Rilke said ‘only man is as if turned in on himself…’ *** because of the awareness of death, contrasting this gaze with the openness of the animal gaze. then I believe that through the sacred, and I believe that Rilke knew this well, we too can have, like the animal, a gaze on the open, and the beauty of this gaze is, in my opinion, that it opens up to an indescribable space-time dimension because it is a gaze-space on life and death at the same time, and I like to imagine this space as the event that occurs at the moment when the last violin note of Olivier Messiaen’s quartet **** is dropped by the piano in a very distant place that seems to be the border of the known universe. Listening to it, it happens that when we perceive the sound physically cease, we hear it continue in a space (the same as that universe? parallel?) within us. First it was outside, then inside.

“Going towards the day” is a title I chose for one of my works and it could work for many. It is a quotation from a saying of the ancient Egyptians who thus considered the moment of the transition from death to life, no sorry I got that wrong, from life to death, or maybe…

notes:* see François Cheng, Five Meditations on Death (or rather on life), translated by Chiara Tartarini, Bollati Boringhieri, 2015

** François Jullienne, Living by Landscape, or the Unthinking of Reason, edited by Francesco Marsciani, Mimesis 2017

*** R.M. Rilke, Elegie Duinesi, translated by Enrico De Portu and Igea DE Portu, Einaudi, 1978