#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistiterview #filippolavaccara

Parola d’Artista: Ciao Filippo, Per la maggior parte degli artisti l’infanzia rappresenta l’età dell’oro quella in cui cominciano a manifestarsi i primi “sintomi” di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. E’ stato così anche per te? Racconta?

Filippo la Vaccara: Più che l’infanzia, è stato nel periodo dell’adolescenza che ho sentito l’urgenza o il desiderio che la scultura e la pittura dovevano essere le attività della vita.

Determinante la mia iscrizione al Liceo Artistico di Catania e, poi, all’Accademia, scuole dove il piacere ha sempre superato l’aspetto della fatica.

L’infanzia però, a pensarci, l’ho vissuta in un clima molto fertile, circondato e cresciuto da zii giovanissimi con grande propensione al disegno, alla musica, al ballo, oltre che a una straordinaria capacità di raccontare le cose con grande senso dell’umorismo.

P. d. A. : Negli anni della tua formazione ci sono stati degli incontri importanti?

F. L. V. : Gli incontri significativi ruotavano attorno all’ambiente della scuola. Alcuni docenti artisti, primo tra tutti il pittore Claudio Marullo, di cui frequentavo lo studio e, poi, diversi colleghi studenti con i quali avevamo persino formato un gruppo artistico, a metà degli anni novanta, realizzando mostre collettive, alcune autogestite, altre con dei curatori (storici o critici dell’arte che insegnavano all’Accademia). Tra questi, due figure di rilievo: Paolo Giansiracusa e Giuseppe Frazzetto.

P. d. A.: Che lavori facevi all’epoca?

F. L. V. : L’influenza maggiore l’ho avuta dalla transavanguardia e dalla pittura internazionale degli anni ottanta. La scoperta di quel variegato “modo” neo – espressionista di operare mi ha suggerito possibilità che mi risultavano congeniali : idea, sintesi e velocità di esecuzione, lavoro manuale, tutto “fai da te”.

Nei miei lavori, oltre a quel mondo, confluivano fattori immaginari legati al territorio che vivevo, all’arte popolare, ai cartoni animati e alle opere di molti miei docenti.

P. d. A.: All’epoca praticavi già anche la scultura?

F. L. V. : Pur frequentando la Scuola di Scultura all’Accademia, dedicavo più tempo alla pittura che al lavoro a tre dimensioni.

Ho incrementato la ricerca scultorea dopo il diploma, a partire dal ’99, anno in cui un mio primo viaggio in India ha risvegliato l’interesse verso questa la pratica che ho poi consolidato ulteriormente frequentando le mostre della Galleria Ala di Milano. Rimasi molto colpito da una grande personale di Gunter Forg in cui l’artista presentava disegni, dipinti e sculture in bronzo.

Oggi dedico lo stesso tempo sia alla scultura sia alla pittura.

P. d. A.: Mi piacerebbe che tu parlassi più diffusamente di questa relazione fra il viaggio in India e la dimensione scultorea nel tuo lavoro?

F. L. V. : I viaggi in india sono sempre stati un bagno di sensazioni: colore, colore dappertutto , sempre odore di cibo, di terra, di pioggia. Le suggestioni ricavate dai luoghi, per me che amo moltissimo guardare, li ho sentiti sulla pelle per molti anni e mi hanno spinto a dedicare a questo paese innanzitutto diversi grandi dipinti.

Realizzavo sul posto disegni dal vero, fotografie e brevi video, tutto materiale che consolida nella mente le impressioni ricavate.

Ovviamente il mio è sempre stato uno sguardo occidentale sull’oriente.

I quadri sull’india posso paragonarli a un reportage appassionato di immagini, mentre per la scultura non c’è stato un incremento di “Indian Style” ma, a mio modo, ho cominciato di più a rappresentare animali (sempre a mio modo) portatori di un qualche messaggio spirituale.

P. d. A.: La dimensione del sacro che importanza ha nel tuo lavoro?

F. L. V. : Ogni lavoro per me deve corrispondere ad una sorta di miracolo, ad un evento unico, frutto di ciò che di meglio può fare l’uomo.

I dipinti e le sculture, quindi, più che raccontare una sacralità, incarnano nella loro materia il concetto del sacro.

Anche nella tradizione cristiana l’uomo è fatto a immagine e somiglianza del divino. Va da se che, nella migliore delle ipotesi, le opere dell’uomo devono essere una emanazione di questa divinità.

Le opere per me sono tanto terrene quanto spirituali, esattamente come l’uomo stesso.

P. d. A.: Nel tuo lavoro, nel tempo, hai in qualche modo definito un territorio di appartenenza una tua iconografia?

F. L. V. : Mi sono accorto che, ciclicamente, i temi di mio interesse ritornano in maniera naturale. Del resto, un dipinto con un certo immaginario, nutre quell’immaginario, ed è per questo che molte immagini si somigliano o sembrano appartenere ad una stessa famiglia, hanno una provenienza comune. Il lavoro artistico per me si basa molto sulla pratica in laboratorio. A volte il mestiere si affina tanto e le opere riescono bene grazie all’abilità, alla casualità, al fare continuo.

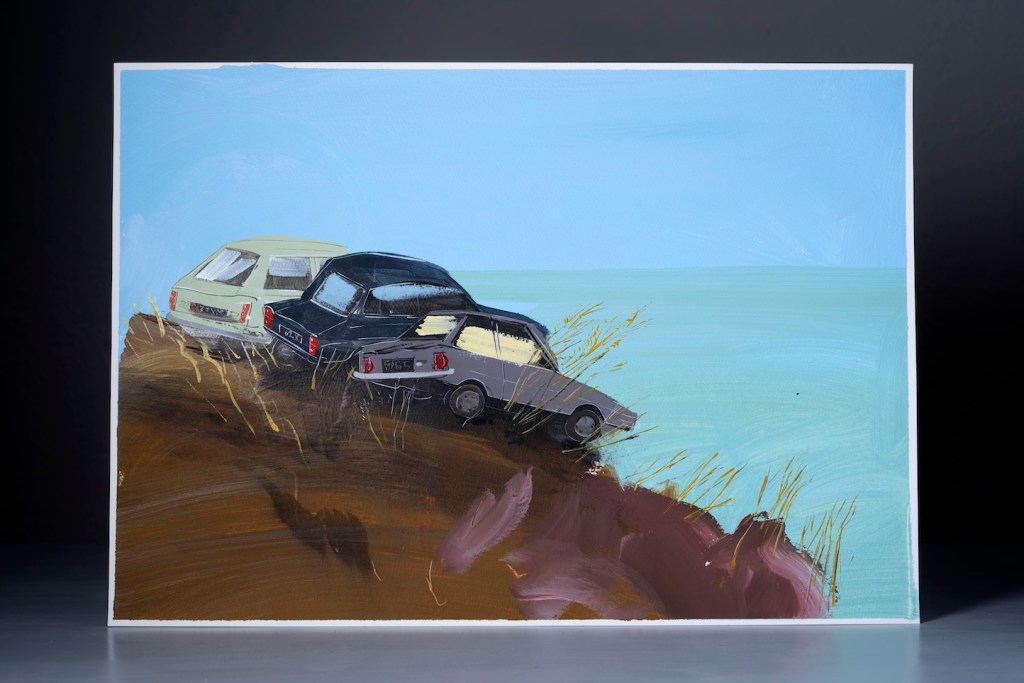

Paesaggio, città, figure. Questi sono i temi centrali che affronto adesso.

Naturalmente la ricerca si evolve come in un processo innato. Il lavoro è in continua evoluzione.

P. d. A.: Quando presenti una serie di lavori insieme ( in occasione di una mostra ad esempio) come lavori sull’allestimento?

F. L. V. : Nelle mostre c’è una componente di casualità come nella realizzazione delle opere. Mi interessa la scelta dei lavori operata da un curatore. Poi, alcune volte partecipo all’allestimento, altre volte meno, altre volte no.

Penso che una mostra sia sempre una messa in scena, perché è costruita con un allestimento che mi fa pensare a un’opera teatrale, effimera, che ha un inizio, uno sviluppo e un finale.

Amo le mostre che durano poco, che si montano e smontano con una certa velocità e facilità.

In questo approccio che guarda alla caducità e alla temporaneità degli allestimenti, cerco di non trascurare il dettaglio, consapevole che allo spettatore non sfugge niente e ha il diritto di visitare una mostra che sia davvero curata.

P. d. A.: Puoi raccontarmi qualcosa di più sulla componente casuale a cui accennavi?

F. L. V. : La casualità c’è sempre. Ad esempio, ho in mente una scultura. Dall’idea al bozzetto, qualcosina cambia. Dal bozzetto alla realizzazione qualcosa cambia ancora. Nel mio lavoro non posso prevedere alla perfezione il risultato e accetto, entro certi limiti, i cambiamenti che avvengono.

Qualche tempo fa allestivo una mostra a San Sebastiano Contemporary, a Palazzolo Acreide. Avevo spedito una scultura in carta e legno con una cassa leggera. Il lavoro è arrivato gravemente danneggiato. Si trattava di una scultura a forma di camioncino che volevo sospendere dal soffitto.

In quel caso, come un carrozziere, ho riparato come meglio potevo la carrozzeria e allestito il pezzo, che portava gli evidenti segni di un incidente. Credo che il lavoro sia molto migliorato. Quella componente del caso ha aggiunto qualcosa al lavoro.

Quando viene un curatore in studio a selezionare le opere per un progetto, quasi sempre sceglie tutte quelle che io avrei scartato o non considerato. Così la mostra avrà un aspetto diverso rispetto alla mia idea iniziale. Anche un evento del genere, che mi piace accogliere, lo associo ad una certa casualità.

P. d. A.: In che posizione ti poni nel confronto del tuo lavoro?

F. L. V. : Mi pongo a servizio del mio lavoro. Non potrebbe essere altrimenti. Per sviluppare un lavoro, dopo l’idea, devo procurare il denaro per l’acquisto del materiale per la sua realizzazione. Poi questo materiale devo andarlo a prendere, sceglierlo, trasportarlo. Azioni evidentemente al servizio dell’idea.

Il momento della realizzazione di un lavoro, che può riuscire o meno, è semplicemente una fase diversa e più avanzata della produzione. Ma la mia posizione di servizio verso l’idea non cambia. Nel lavoro l’artista deve sparire il più possibile.

P. d. A.: Che importanza ha nel tuo lavoro il disegno?

F. L. V. : Direi che è alla base di tutto.

Gli schizzi nascono sotto forma di disegno sia per i dipinti che per le sculture.

L’impostazione di un quadro avviene tramite il disegno, e il quadro stesso spesso si conclude con una forma di disegno lineate che definisce alcuni contorni delle figure.

Poi c’è il disegno dal vero che si aggiunge ai lavori, praticato specialmente quando sono fuori e lontano dallo studio. In questi casi il disegno per me sostituisce la fotografia, è un modo per restare in confidenza con la rappresentazione di luoghi reali. E’ un esercizio che mi tiene preparato quando poi inventarò delle scene.

P. d. A.: Ecco, giusto appunto, ti volevo chiedere di parlare dell’idea di messa in scena del tuo lavoro?

F. L. V. : L’immagine dipinta è una scena virtuale. Una messa in scena.

Anche nel caso della scultura, il soggetto rappresentato è messo in scena, viene alla luce. In mostra è sotto il riflettore e recita la sua parte ogni volta che viene osservato. Qualunque oggetto ha il potere di rappresentare se stesso. Nel caso della rappresentazione scultorea, il gioco della rappresentazione si fa più complesso (soggetto reale, sua rappresentazione in scultura, somiglianza, ecc.

L’opera è uno spettacolo preparato per l’osservatore. Credo che un opera visiva, come un’opera musicale, abbia una sua narrazione, un suo tempo, un suo sviluppo nell’osservazione, e un finale. Il tutto condensato in un unico pezzo.

P. d. A.: Questa idea di condensazione in un unico pezzo sembra stridere con l’idea di racconto, per come ci siamo abituati a pensare al racconto con la letteratura ad esempio, dove è l’elemento temporale ad inanella lo scorrere della narrazione, portando con se un’idea di molteplicità non trovi?

F. L. V. : Amo la capacità dei quadri, delle sculture e della fotografia di condensare in una sola immagine una “storia” o “più storie”.

Si tratta di immagini di cose viste o immaginate. O entrambe le cose. Frame di luoghi, o di personaggi.

In ogni passaggio di colore, di sfumatura, di superficie, c’è una “narrazione”, è la narrazione del colore stesso, della sfumatura, e cose via.

La storia che può accennare una scultura è una storia segreta. Il personaggio ritratto, reale o immaginario, non svela nulla di sei si offre allo sguardo dell’ osservatore con le sue fattezze.

Il racconto si sviluppa, con l’osservazione, tra pubblico e opera. Il racconto lo crea lo spettatore assieme al lavoro. Semmai, l’opera innesca la storia, che è un pensiero, che sono dei pensieri.

P. d. A.: Che rapporto esiste nel tuo lavoro con le categorie di tempo e spazio?

F. L. V. : Il tempo e lo spazio nell’opera sono largamente dilatati, distorti, forzati, modificati, semplificati, condensati, ecc..

Nel paesaggio dipinto a volte c’è un riferimento a un luogo reale ma solamente nelle suggestioni.

Mi piace, nel lavoro, l’idea di una collocazione indefinita nel tempo e nello spazio.

P. d. A.: La presenza dell’osservatore o spettatore dell’opera è per te una condizione necessaria all’esistenza dell’opera stessa? Voglio dire, l’opera esiste solo nel momento in cui c’è qualcuno che la osserva?

F. L. V. : Lo spettatore ha la grande libertà di giudicare l’opera, di ammirarla, di innamorarsene, oppure può provare indifferenza o avere opinioni negative. Il sentimento che genera l’opera, non può che nascere dall’incontro con l’ osservatore.

Materialmente l’opera esiste anche quando nessuno la contempla. Ma è nel momento della visione che si rigenera, che rinasce. Quando nessuno guarda l’opera è come se questa stesse vivendo la fase del sonno. Esiste inconsapevolmente.

FILIPPO LA VACCARA

Filippo La Vaccara, nasce a Catania nel 1972, vive e lavora a Milano. Si diploma in Scultura all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Catania nel1994. Il suo percorso artistico inizia nel 1998, con una mostra personale curata da Francesca Pasini presso Viafarini a Milano. Nel1999 è selezionato da Angela Vettese e Giacinto Di Pietrantonio per il Corso Superiore di Arti Visive presso la Fondazione Antonio Ratti di Como, dove ha seguito uno stage con Haim Steinbach. Nel 2002 è invitato come Artist in Residence alla Fondazione Orestiadi di Gibellina, dove realizza cinque quadri di grandi dimensioni poi esposti nella mostra Laboratorio, curata da Achille Bonito Oliva e attualmente parte della collezione del Museo. Nel 2015 due sue opere, di proprietà della Collezione Mario e Bianca Bertolini, sono state acquisite dal Museo del Novecento di Milano. Nel 2016 una sua opera viene premiata e acquisita dalla Fondazione Focus Abengoa di Siviglia.Nello stesso anno riceve un premio dalla Fondazione Pollock – Krasner Foundation per la realizzazione di un libro monografico edito da Allemandi. Nel 2021 espone alcune opere al Museo di Cultura Bizantina di Salonicco e al Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Palazzo Belmonte Riso di Palermo. E’ in preparazione un suo libro monografico edito da Balloon Project.

Eglish text

Interview whit Filippo La Vaccara

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #artistiterview #filippolavaccara

Parola d’Artista: Hi Filippo, For most artists, childhood represents the golden age when the first ‘symptoms’ of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Do tell?

Filippo la Vaccara: More than childhood, it was in my adolescence that I felt the urgency or desire that sculpture and painting should be the activities of life.

It was decisive that I enrolled in the Liceo Artistico in Catania and then in the Accademia, schools where pleasure always overcame hard work.

My childhood, however, if you think about it, I lived it in a very fertile climate, surrounded and raised by very young uncles with a great propensity for drawing, music, dancing, as well as an extraordinary ability to tell things with a great sense of humour.

P. d. A. : During your formative years, were there any important encounters?

F. L. V. : The significant encounters revolved around the school environment. Some teachers were artists, first and foremost the painter Claudio Marullo, whose studio I frequented and, then, several fellow students with whom we had even formed an artistic group, in the mid-1990s, holding group exhibitions, some self-managed, others with curators (art historians or critics who taught at the Academy). Among them, two prominent figures: Paolo Giansiracusa and Giuseppe Frazzetto.

P. d. A. : What jobs did you do at that time?

F. L. V. : I was most influenced by the Transavantgarde and the international painting of the 1980s. The discovery of that varied neo-expressionist “way” of working suggested possibilities that were congenial to me: idea, synthesis and speed of execution, manual work, everything “do-it-yourself”.

In addition to that world, imaginary factors linked to the area I lived in, popular art, cartoons, and the works of many of my teachers flowed into my works.

P. d. A.: Were you already practising sculpture at that time?

F. L. V. : Although I attended the School of Sculpture at the Academy, I devoted more time to painting than to three-dimensional work.

I increased my sculptural research after graduation, starting in ’99, the year in which my first trip to India awakened my interest in this practice, which I then further consolidated by attending exhibitions at the Ala Gallery in Milan. I was very impressed by a large solo exhibition of Gunter Forg in which the artist presented drawings, paintings and bronze sculptures.

Today, I dedicate the same amount of time to both sculpture and painting.

P. d. A.: I would like you to talk more about this relationship between the trip to India and the sculptural dimension in your work?

F. L. V. : Travelling in India has always been a bath of sensations: colour, colour everywhere, always the smell of food, of earth, of rain. The suggestions drawn from the places, for me who loves to look a lot, I have felt them on my skin for many years and they have prompted me to dedicate several large paintings to this country in the first place.

I made on-site drawings from life, photographs and short videos, all material that consolidated the impressions gained in my mind.

Of course, mine has always been a Western view of the East.

The paintings on India I can compare to a passionate reportage of images, while for sculpture there was no increase in ‘Indian Style’ but I started more to represent animals (again in my own way) as bearers of some spiritual message.

P. d. A.: How important is the dimension of the sacred in your work?

F. L. V. : Every work for me must correspond to a kind of miracle, a unique event, the result of the best that man can do.

Paintings and sculptures, therefore, rather than recounting a sacredness, embody in their material the concept of the sacred.

Even in the Christian tradition, man is made in the image and likeness of the divine. It goes without saying that, at best, the works of man must be an emanation of this divinity.

Works for me are as earthly as they are spiritual, just like man himself.

P. d. A.: In your work, over time, have you in any way defined an iconography of your own?

F. L. V. : I have realised that, cyclically, themes of my interest naturally return. After all, a painting with a certain imagery, nourishes that imagery, and that is why many images look similar or seem to belong to the same family, they have a common origin. Art work for me is very much based on practice in the workshop. Sometimes the craft is honed so much and the works succeed because of skill, randomness, continuous doing.

Landscape, city, figures. These are the central themes I deal with now. Of course the research evolves as in an innate process. The work is constantly evolving.

P. d. A.: When you present a series of works together (at an exhibition for example) how do you work on the set-up?

F. L. V. : There is an element of randomness in exhibitions as there is in the realisation of works. I am interested in the choice of works made by a curator. Then, sometimes I participate in the staging, sometimes less, sometimes not.

I think that an exhibition is always a staging, because it is constructed with a set-up that makes me think of a play, ephemeral, that has a beginning, a development and an ending.

I love exhibitions that last a short time, that can be assembled and disassembled with a certain speed and ease.

In this approach that looks at the transience and temporariness of exhibitions, I try not to neglect detail, aware that the viewer does not miss anything and has the right to visit an exhibition that is truly curated.

P. d. A.: Can you tell me more about the random component you mentioned?

F. L. V. : Randomness is always there. For example, I have a sculpture in mind. From the idea to the sketch, something changes. From the sketch to the realisation, something still changes. In my work, I cannot predict the result perfectly and I accept, within certain limits, the changes that occur.

Some time ago I had an exhibition at San Sebastiano Contemporary in Palazzolo Acreide. I had sent a paper and wood sculpture in a light box. The work arrived badly damaged. It was a truck-shaped sculpture that I wanted to suspend from the ceiling.

In that case, like a coachbuilder, I repaired the bodywork as best I could and set up the part, which bore the obvious signs of an accident. I think the work improved a lot. That component of the case added something to the work.

When a curator comes to the studio to select works for a project, he almost always chooses all those that I would have discarded or not considered. So the exhibition will look different from my initial idea. Even such an event, which I like to welcome, I associate it with a certain randomness.

P. d. A.: Where do you stand in the comparison of your work?

F. L. V. : I place myself at the service of my work. It could not be otherwise. To develop a work, after the idea, I have to procure the money to buy the material for its realisation. Then this material I have to fetch it, choose it, transport it. Actions obviously at the service of the idea.

The moment of realisation of a work, which may or may not succeed, is simply a different and more advanced phase of production. But my position of service to the idea does not change. In the work, the artist must disappear as much as possible.

P. d. A.: How important is drawing in your work?

F. L. V. : I would say that it is the basis of everything.

Sketches originate in the form of drawings for both paintings and sculptures.

The setting up of a painting is done through drawing, and the painting itself often ends with a form of line drawing that defines certain contours of the figures.

Then there is the life drawing that is added to the work, practised especially when I am out and away from the studio. In these cases, drawing replaces photography for me, it is a way to stay familiar with the representation of real places. It is an exercise that keeps me prepared when I later invent scenes.

P. d. A.: That’s right, I wanted to ask you about the idea of staging your work?

F. L. V. : The painted image is a virtual scene. A staging.

Also in the case of sculpture, the subject represented is staged, it comes to light. It is in the spotlight and plays its part every time it is observed. Any object has the power to represent itself. In the case of sculptural representation, the game of representation becomes more complex (real subject, its representation in sculpture, resemblance, etc.).

The work is a performance prepared for the observer. I believe that a visual work, like a musical work, has its own narrative, its own tempo, its own development in observation, and an ending. All condensed into one piece.

P. d. A.: This idea of condensation in a single piece seems to clash with the idea of storytelling, the way we are used to thinking of storytelling with literature for example, where it is the temporal element that loops the flow of the narrative, bringing with it an idea of multiplicity don’t you find?

F. L. V. : I love the ability of paintings, sculptures and photography to condense a “story” or “several stories” into a single image.

They are images of things seen or imagined. Or both. Frames of places, or of characters.

In each passage of colour, of nuance, of surface, there is a ‘narrative’, it is the narrative of the colour itself, of the nuance, and so on.

The story that a sculpture can hint at is a secret story. The character portrayed, whether real or imaginary, reveals nothing of six offers itself to the observer’s gaze with its features.

The story develops, through observation, between the public and the work. The spectator creates the tale together with the work. If anything, the work triggers the story, which is a thought.

P. d. A.: What relationship exists in your work with the categories of time and space?

F. L. V. : Time and space in the work are largely dilated, distorted, forced, modified, simplified, condensed, etc..

In the painted landscape there is sometimes a reference to a real place, but only in suggestions.

I like the idea of an indefinite location in time and space in the work.

P. d. A.: For you, is the presence of the observer or viewer of the work a necessary condition for the existence of the work itself? I mean, does the work only exist in the moment in which there is someone observing it?

F. L. V. : The viewer has great freedom to judge the work, to admire it, to fall in love with it, or they can feel indifference or have negative opinions. The feeling that generates the work can only arise from the encounter with the observer.

Materially, the work exists even when no one contemplates it. But it is in the moment of viewing that it is regenerated, that it is reborn. When no one looks at the work, it is as if it were going through the sleeping phase. It exists unconsciously.

FILIPPO LA VACCARA

Filippo La Vaccara, born in Catania in 1972, lives and works in Milan. He graduated in Sculpture from the Academy of Fine Arts in Catania in 1994. His artistic career began in 1998, with a solo exhibition curated by Francesca Pasini at Viafarini in Milan. In1999 he was selected by Angela Vettese and Giacinto Di Pietrantonio for the Advanced Course in Visual Arts at the Antonio Ratti Foundation in Como, where he followed an internship with Haim Steinbach. In 2002 he was invited as Artist in Residence to the Fondazione Orestiadi di Gibellina, where he produced five large paintings that were later exhibited in the exhibition Laboratorio, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and currently part of the museum’s collection. In 2015, two of his works, owned by the Mario and Bianca Bertolini Collection, were acquired by the Museo del Novecento in Milan. In 2016 one of his works was awarded and acquired by the Focus Abengoa Foundation in Seville. In the same year he received an award from the Pollock – Krasner Foundation for a monographic book published by Allemandi. In 2021, he exhibited some works at the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki and at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Palazzo Belmonte Riso in Palermo. A monographic book published by Balloon Project is in preparation.