#paroladartista #intervistaartista #gregoriobotta

▼Scroll down for English version

Gabriele Landi: Per la maggior parte degli artisti l’infanzia rappresenta l’età dell’oro quella in cui cominciano a manifestarsi i primi sintomi di una certa propensione ad appartenere al mondo dell’arte. E’ stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Gregorio Botta: No, in realtà da bambino non avevo nessuna inclinazione artistica: forse perché la mia è stata un’infanzia felice, molto. Sono stati gli anni difficili dell’adolescenza quelli in cui si è manifestato il primo desiderio di arte: a 14 anni ho cominciato a dipingere, e ricordo che solo mentre dipingevo il tempo si annullava completamente. Il pomeriggio volava, era magnifico. Avevo una buona mano, volevo iscrivermi al liceo artistico, ma la mia famiglia era contraria. Poi scoppiò il ‘68, la vita e la politica mi portarono altrove. Fu come dimenticare la mia vera passione, e con lei me stesso. Mi risvegliai solo quando cominciai a lavorare all’Unità. Il mestiere al giornale mi piaceva molto, ma capii presto che non potevo fare solo quello: mi sentivo soffocare. Così mi iscrissi all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma, a scenografia, per poter seguire le meravigliose lezioni di Toti Scialoja.

G.L.: Come erano le lezioni di Toti Scialoja?

G.B.: Era un uomo davvero speciale: stava in cattedra naturalmente, senza dare l’impressione di starci. Aveva un carisma naturale, al quale si accompagnava una eleganza innata e una dolce trasparenza. Si mostrava a noi studenti nella sua verità, senza finzioni. Ci raccontava gli episodi più intimi della sua vita, se era depresso ce lo diceva, e così se era triste o desolato: passava la mano sulla bella testa calva e raccontava. Era un uomo molto colto, un poeta raffinato, parlava benissimo: un incantatore, un seduttore. Aveva avuto una vita ricca, era stato a lungo in America, era stato amico di De Kooning e Rothko, e aveva contribuito a far conoscere l’espressionismo astratto in Italia. La “pittura di superficie” – anti prospettica e anti naturaista – per lui era un credo intoccabile. Ricordo con che desolazione parlava della Transavanguardia: la sentiva come un tradimento. Sapeva essere caustico davanti ai nostri lavori, ma era sempre presente e affettuoso: veniva alle nostre prime mostre, alle nostre cene portando gran bottiglie di champagne e qualche volta andavamo da Cesaretto tutti insieme. Mi chiese una volta di fargli da assistente, Nunzio aveva già preso il volo: gli dissi di no e forse fu uno sbaglio. Ma è inutile chiederselo ora.

G.L.: Dopo gli studi come prosegue questa avventura?

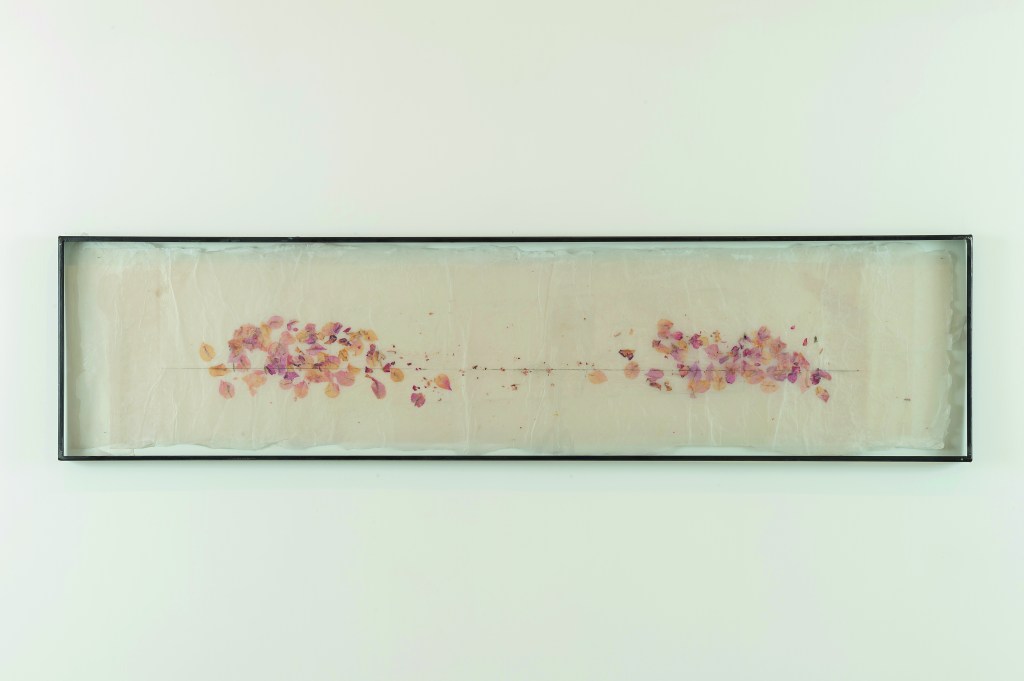

G.B.: È cominciata la mia doppia vita: la mattina a studio e il pomeriggio al giornale. Prima l’Unità e poi, dall’84, Repubblica. Sono stato fortunato. Già mentre ero all’Accademia un uomo molto generoso, Maurizio Morellini, che era stato l’assistente di Mirko Basaldella, mi ha ospitato nello studio dello scultore che lui ancora usava. Mi ha insegnato un sacco di cose, soprattutto mi ha fatto scoprire la cera: ed è così che è diventato la mia materia d’elezione: la sentivo come un elemento che mi corrispondeva perfettamente. Morbida e ricettiva, diafana, sincera, corposa: usata pittoricamente, come la usavo io all’inizio, registrava tutti i movimenti del pennello, se sbagliavi non c’era modo di correggere. Buttavi e ricominciavi. Una pelle che registrava i segni del tempo. Un campo aperto pronto ad accogliere ogni immagine, ogni colore, un’attesa di un evento che deve compiersi. I miei primi quadri erano così: velature su velature di tempera su juta, e al centro un campo di cera, una tabula rasa che aspettava il suo compimento.

Feci le prime mostre con Ludovico Pratesi, nell’89 e poi cominciai subito la mia collaborazione con Il Segno. Ricordo l’emozione e la paura, quando per la prima volta Angelica Savinio e la figlia Francesca Antonini vennero a studio. Gli piacerà il lavoro? O mi diranno di lasciar perdere? Gli piacque.

G.L.: Quindi cominciasti a lavorare con loro, le cose come andarono avanti?

G.B.: “L’arte è un’amante esigente” diceva sempre Scialoja. Ma io ero un traditore. Come ti dicevo mi dividevo tra l’atelier e il giornale. Questo ha probabilmente rallentato il mio percorso artistico: ma mi ha dato anche un grande vantaggio. Il fatto di non dover dipendere economicamente dall’arte mi ha dato una grandissima libertà creativa. L’amore per la cera mi ha spinto ad usare altri materiali naturali: fuoco, acqua, vetro, piombo e ora l’alabastro. La dimensione dello scorrere del tempo è entrata sempre più nel mio lavoro. Comunque, malgrado il giornale, sono riuscito a fare molte personali : al Segno, che poi ha cambiato nome in Francesca Antonini Arte contemporanea, alla Fondazione Volume, allo studio Trisorio di Napoli, alla Galleria dello scudo di Verona, in Svizzera, a Bruxelles, da Peola-Simondi a Torino, allo studio G7 di Bologna, e in altre gallerie. Il mio lavoro è stato esposto in luoghi pubblici come i Magazzini del Sale a Siena, a Palazzo Te a Mantova, al Mart, al Maxxi, al Madre, al Macro, e alla Galleria nazionale di Roma, che nel 2021 ha ospitato la mia personale “Just measuring uncounsciosness” . Una mia installazione è anche presente nel museo diffuso della Metropolitana di Napoli.

G.L.: Parliamo della dimensione del tempo come si inserisce nel tuo lavoro?

G.B.: Il passo dalla cera al fuoco è breve. È cominciato tutto così: vedendo trasformarsi la cera con la fiamma, passare dallo stato solido a quello liquido e viceversa, cambiare forma. Una meraviglia. La cera è un esatto, implacabile, testimone del tempo. Costruii una macchina semplice: una tavola di cera da cinque chili appesa ad un bilanciere, davanti ad essa una fila di fiamme alimentate da una bombola a gas. Man a mano che la tavola si scioglieva, perdeva peso e saliva verso l’alto, esponendosi così tutta al fuoco e fondendosi completamente. E poi il ciclo ricominciava. Ho chiamato questa scultura Mergellina, che è il quartiere di Napoli dove sono nato. Non ci ho pensato allora, ma ci penso adesso: un titolo che parla di nascita.

Il fuoco è tempo che si consuma, è vita che si svolge, energia che si diffonde. Ho creato molte sculture con il fuoco: ad esempio il Mart di Rovereto ha esposto “Respiro” – costruita con la collaborazione del mio amico Felice Farina, un regista che è un mago della meccanica e dell’elettronica. Era una lunga lama metallica con nove fiamme che venivano accese dal passaggio di una decima fiamma, e poi, una a una, in modo random, si spegnevano grazie ad un soffio che Felice aveva magicamente creato. Sembrava proprio che esalassero l’ultimo respiro. Una volta spente tutte, il ciclo ricominciava.

Ultimamente è entrato nel mio linguaggio anche il suono: con Orbite, ad esmpio, dove cinque campane tibetane ruotano in orbite diverse e un batacchio le colpisce in modo casuale e imprevedibile.

Ma naturalmente anche tutto il lavoro con l’acqua riguarda il tempo: le sculture di cera e di piombo con i versi da cui sgorgano piccoli flussi d’acqua (come quella di Rifugi, al Macro) parlano dell’impermanenza, del lento passaggio di ogni cosa. La lapide di Keats al cimitero degli inglesi di Roma mi ha ispirato moltissimo: “Qui giace uno il cui nome è scritto sull’acqua”. Il poeta non ci volle il suo nome, convinto che sarebbe stato dimenticato. Sbagliava, ma che lezione quell’epitaffio. Scrivere sull’acqua: non è ciò che facciamo tutti vivendo?

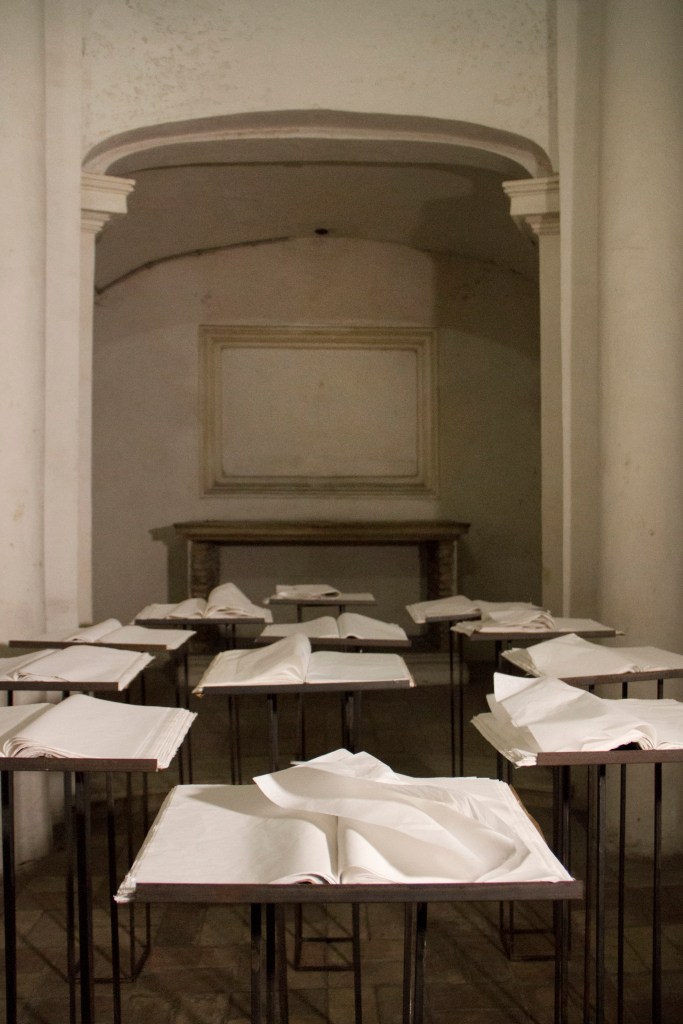

Infine, il tempo entra anche nei lavori che non si muovono: i marmi, i vetri, le carte di riso cerate. In tutte le forme che vi appaiono non sono perfettamente visibili, sembra che stiano affiorando o immergendosi in un altrove. Non c’è mai niente di stabile nel mondo. Il tempo è il grande mistero nel quale siamo immersi.

G.L.: Gregorio nel tuo lavoro l’idea di messa in scena ha una qualche importanza?

G.B.: Non si tratta di mettere in scena, ma di sottrarre dalla scena: creare uno spazio per l’assenza, il vuoto, il silenzio. L’importante è dare forma non ad una scena ma ad un luogo, non ad una rappresentazione ma ad una presenza. Creare uno spazio offerto al mistero. Ma se intendi chiedermi se per me è importante la scrittura di una mostra, allora ti rispondo ovviamente di sì.

G.L.: Puoi spiegare meglio cosa intendi per: “scrittura di una mostra”?

G.B.: È una definizione che usa sempre Achille Bonito Oliva. Una mostra non è una semplice somma di opere. Ma, come dicevo prima, è la creazione di uno spazio, uno spazio che abbia una sua ragione d’essere, una sua presenza, un suo respiro. I giapponesi hanno una bella parola, kami, che significa – ma la traduzione è grossolana – spirito. Alcuni luoghi, o alcuni alberi o pietre, ce l’hanno. Altri no. Ecco, la mostra deve avere kami. Per me vuol dire scegliere con cura ogni opera, proprio come se si stesse facendo un’opera. Uno deve entrare nello spazio e sentirsene avvolto, deve percepirne l’energia, l’atmosfera. Sei mai stato nello studio di Ettore Spalletti? Era un luogo, perfetto, magico: l’esempio più esatto di quel che intendo. Ettore lo abitava come la casa della sua anima. E chi vi entrava poteva abitarla con lui.

G.L.: Cerchi, oltre che un dialogo fra le opere che abitano lo spazio, con lo spazio stesso?

G.B.: Certo. Ci sono luoghi che ispirano opere che altrimenti non sarebbero nate. Opere che nascono da un luogo e solo in quello possono vivere. Opere che ancora non sono venute al mondo perché non hanno trovato lo spazio adatto. Quando feci la mostra al Forte di Bard, per esempio, progettai un’opera per una scala ripida e ormai inaccessibile: se ne potevano vedere solo l’inizio in basso e la fine in alto attraverso due vetrate. In passato era usata per accedere alla Fortezza, ma poi è stata chiusa. Avevo immaginato una piccola teleferica che trasportasse su e giù una lampada a olio che illuminasse il buio anche dove il nostro sguardo non poteva spingersi. Si sarebbe chiamata “Vedi per me”.

Ma poi non mi hanno dato il permesso di usare qu più belli sono abitati da opere che devono ancora venire al mondo! Q

Gregorio Botta nasce a Napoli il 18 aprile 1953 ma fa i suoi studi a Roma, frequenta il corso di Toti Scialoja all’Accademia di Belle Arti dove si diploma. Inizia ad esporre dal 1990, in numerose città italiane e all’estero. La prima personale è alla galleria “Il Segno” di Roma (ora Francesca Antonini arte contemporanea), espone – tra l’altro – allo Studio Trisorio, (Napoli), alla Galleria dello Scudo di Verona, al Ponte di Firenze, allo Studio G7 di Bologna, alla Galleria Peola e Simondi di Torino, alla Montoro 12 Gallery di Bruxelles e in numerose altre gallerie. Molte anche le mostre in spazi pubblici: sue personali sono state ospitate nei Musei di Arte contemporanea di Santiago del Cile e di Lima, ai Magazzini del Sale di Piazza del Campo a Siena, al Forte di Bard, all’ex Pescheria di Pesaro, al Macro di Roma e infine alla Galleria Nazionale di Roma (Just measuring uncousciousness è il titolo della mostra allestita nel 2020). Le sue opere sono nelle collezioni del Maxxi e della Galleria nazionale di Roma, del Madre di Napoli, del Mart di Rovereto, della Bce a Francoforte, della Certosa di Padula e nel museo diffuso della metropolitana di Napoli.

Ha scritto “Pollock e Rothko, il gesto e il respiro” (Einaudi Stile Libero, 2020), e “Paul Klee, genio e regolatezza”, (Laterza).

English version

Interview with Gregorio Botta

#wordartist #interviewartist #gregoriobotta

Gabriele Landi: For most artists, childhood represents the golden age when the first symptoms of a certain propensity to belong to the art world begin to appear. Was that the case for you too? Tell us.

Gregorio Botta: No, actually as a child I had no artistic inclination: perhaps because mine was a happy childhood, very much so. It was the difficult years of adolescence when the first desire for art manifested itself: when I was 14, I started painting, and I remember that just while I was painting, time was completely cancelled. The afternoons flew by, it was wonderful. I had a good hand, I wanted to enrol in art school, but my family was against it. Then ’68 broke out, life and politics took me elsewhere. It was like forgetting my true passion, and with it myself. I only woke up when I started working at L’Unità. I really liked my job at the newspaper, but I soon realised that I could not do just that: I felt suffocated. So I enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, in scenography, to be able to follow the wonderful lessons of Toti Scialoja.

G.L.: What were Toti Scialoja’s lessons like?

G.B.: He was a very special man: he sat at his desk naturally, without giving the impression of being there. He had a natural charisma, which was accompanied by an innate elegance and sweet transparency. He showed himself to us students in his truth, without pretence. He would tell us the most intimate episodes of his life, if he was depressed he would tell us, and likewise if he was sad or desolate: he would pass his hand over his beautiful bald head and recount. He was a very cultured man, a refined poet, he spoke beautifully: a charmer, a seducer. He had had a rich life, he had been in America for a long time, he had been friends with De Kooning and Rothko, and he had helped introduce abstract expressionism in Italy. Surface painting’ – anti-perspective and anti-nature – was an untouchable creed for him. I remember with what desolation he spoke of Transavantgarde: he felt it to be a betrayal. He could be caustic in front of our works, but he was always present and affectionate: he came to our first exhibitions, to our dinners carrying large bottles of champagne, and sometimes we all went to Cesaretto’s together. He asked me once to be his assistant, Nunzio had already taken off: I told him no and maybe that was a mistake. But it is useless to wonder about that now.

G.L.: After your studies, how did this adventure continue?

G.B.: My double life began: mornings at the studio and afternoons at the newspaper. First L’Unità and then, from 1984, Repubblica. I was lucky. Even while I was at the Academy a very generous man, Maurizio Morellini, who had been Mirko Basaldella’s assistant, hosted me in the sculptor’s studio that he still used. He taught me a lot of things, above all he made me discover wax: and that is how it became my material of choice: I felt it as an element that matched me perfectly. Soft and receptive, diaphanous, sincere, full-bodied: used pictorially, as I used it at the beginning, it registered all the movements of the brush, if you made a mistake there was no way to correct it. You threw it away and started again. A skin that recorded the signs of time. An open field ready to welcome every image, every colour, a waiting for an event to take place. My first paintings were like this: veils upon veils of tempera on jute, and in the centre a field of wax, a tabula rasa waiting for its fulfilment.

I did my first exhibitions with Ludovico Pratesi, in ’89, and then I immediately began my collaboration with Il Segno. I remember the emotion and fear when for the first time Angelica Savinio and her daughter Francesca Antonini came to the studio. Will they like the work? Or will they tell me to forget it? They liked it.

G.L.: So you started working with them, how did things go on?

G.B.: ‘Art is a demanding lover,’ Scialoja used to say. But I was a traitor. As I told you, I divided my time between the atelier and the newspaper. This probably slowed down my artistic career: but it also gave me a great advantage. Not having to depend financially on art gave me a great deal of creative freedom. My love for wax has pushed me to use other natural materials: fire, water, glass, lead and now alabaster. The dimension of the passage of time has increasingly entered my work. However, in spite of the newspaper, I managed to have many solo exhibitions: at Segno, which then changed its name to Francesca Antonini Arte contemporanea, at the Fondazione Volume, at the Trisorio studio in Naples, at the Galleria dello scudo in Verona, in Switzerland, in Brussels, at Peola-Simondi in Turin, at the G7 studio in Bologna, and in other galleries. My work has been exhibited in public venues such as the Magazzini del Sale in Siena, Palazzo Te in Mantua, Mart, Maxxi, Madre, Macro, and the National Gallery in Rome, which hosted my solo exhibition ‘Just measuring uncounsciosness’ in 2021. One of my installations is also in the diffuse museum of the Naples Metro.

G.L.: Let’s talk about the dimension of time, how does it fit into your work?

G.B.: The step from wax to fire is short. It all started like that: watching the wax transform with the flame, going from the solid state to the liquid state and vice versa, changing shape. A wonder. Wax is an exact, relentless witness of time. I built a simple machine: a five-kilo plank of wax hung from a balance, in front of it a row of flames fed by a gas cylinder. As the board melted, it would lose weight and rise upwards, thus exposing itself to the fire and melting completely. And then the cycle would begin again. I called this sculpture Mergellina, which is the neighbourhood in Naples where I was born. I did not think of it then, but I think of it now: a title that speaks of birth.

Fire is time that is consumed, it is life that unfolds, energy that spreads. I have created many sculptures with fire: for example, the Mart in Rovereto exhibited ‘Respiro’ – built with the collaboration of my friend Felice Farina, a director who is a wizard of mechanics and electronics. It was a long metal blade with nine flames that were lit by the passage of a tenth flame, and then, one by one, in a random way, they were extinguished thanks to a breath that Felice had magically created. They seemed to breathe their last breath. Once they were all extinguished, the cycle would begin again.

Lately, sound has also entered my language: with Orbits, for example, where five Tibetan bells rotate in different orbits and a clapper strikes them in a random and unpredictable way.

But of course all the work with water is also about time: the wax and lead sculptures with verses from which small streams of water flow (like the one in Rifugi, at the Macro) speak of impermanence, of the slow passage of everything. Keats’ gravestone at the English cemetery in Rome inspired me greatly: ‘Here lies one whose name is written on water’. The poet did not want his name there, convinced that it would be forgotten. He was wrong, but what a lesson that epitaph was. Writing on water: isn’t that what we all do in life?

Finally, time also enters into the works that do not move: the marbles, the glass, the waxed rice paper. In all the forms that appear there are not perfectly visible, they seem to be surfacing or plunging into an elsewhere. There is never anything stable in the world. Time is the great mystery in which we are immersed.

G.L.: Does the idea of staging have any importance in your work?

G.B.: It is not a question of staging, but of subtracting from the scene: creating a space for absence, emptiness, silence. The important thing is to give form not to a scene but to a place, not to a performance but to a presence. To create a space offered to mystery. But if you mean to ask me whether it is important for me to write an exhibition, then I would obviously say yes.

G.L.: Does the idea of staging have any importance in your work, Gregorio?

G.B.: It is not a question of staging, but of subtracting from the scene: creating a space for absence, emptiness, silence. The important thing is to give form not to a scene but to a place, not to a performance but to a presence. To create a space offered to mystery. But if you mean to ask me if writing an exhibition is important to me, then I would obviously say yes.

G.L.: Can you explain better what you mean by: “writing an exhibition”?

G.B.: It is a definition that Achille Bonito Oliva always uses. An exhibition is not a simple sum of works. But, as I said before, it is the creation of a space, a space that has its own reason for being, its own presence, its own breath. The Japanese have a beautiful word, kami, which means – but the translation is crude – spirit. Some places, or some trees or stones, have it. Others do not. Here, the exhibition must have kami. For me, it means choosing each work carefully, just as if one were making an opera. One must enter the space and feel enveloped by it, one must feel its energy, its atmosphere. Have you ever been in Ettore Spalletti’s studio? It was a place, perfect, magical: the most exact example of what I mean. Ettore inhabited it as the house of his soul. And whoever entered it could inhabit it with him.

G.L.: Are you looking not only for a dialogue between the works that inhabit the space, but also with the space itself?

G.B.: Of course. There are places that inspire works that otherwise would not have come into being. Works that are born from a place and only in that place can they live. Works that have not yet come into the world because they have not found the right space. When I did the exhibition at the Fortress of Bard, for example, I designed a work for a steep and now inaccessible staircase: you could only see the beginning at the bottom and the end at the top through two glass windows. In the past it was used to access the Fortress, but then it was closed. I had imagined a small cable car that would carry an oil lamp up and down, illuminating the darkness even where our gaze could not go. It would have been called ‘See for Me’.

But then I didn’t get permission to use the most beautiful ones are inhabited by works that have yet to come into the world! Q

Gregorio Botta was born in Naples on 18 April 1953 but did his studies in Rome, attending Toti Scialoja’s course at the Academy of Fine Arts where he graduated. He began exhibiting in 1990, in numerous Italian cities and abroad. His first solo exhibition was at the ‘Il Segno’ gallery in Rome (now Francesca Antonini arte contemporanea), he exhibited – amongst others – at Studio Trisorio, (Naples), Galleria dello Scudo in Verona, Ponte in Florence, Studio G7 in Bologna, Galleria Peola e Simondi in Turin, Montoro 12 Gallery in Brussels and numerous other galleries. He has also had many exhibitions in public spaces: his solo shows have been hosted in the Museums of Contemporary Art in Santiago de Chile and Lima, the Magazzini del Sale in Piazza del Campo in Siena, the Forte di Bard, the former Pescheria in Pesaro, the Macro in Rome and finally the Galleria Nazionale in Rome (Just measuring uncousciousness is the title of the exhibition set up in 2020). His works are in the collections of the Maxxi and the Galleria Nazionale in Rome, the Madre in Naples, the Mart in Rovereto, the Bce in Frankfurt, the Certosa in Padula and in the diffuse museum of the Naples underground.

He has written “Pollock and Rothko, the Gesture and the Breath” (Einaudi Stile Libero, 2020), and “Paul Klee, Genius and Regulation”, (Laterza).