#paroladartista #intervistaartista #riccardogemma

▼scroll down for English version

Gabriele Landi: Ciao Riccardo, per la maggior parte degli artisti i primi “sintomi” di questa grave malattia chiamata arte si manifestano già nella prima infanzia nelle maggior parte dei casi in modo inconsapevole, talvolta trasmessi da parenti più o meno prossimi. È successo così anche a te, racconta?

Riccardo Gemma: La prima cosa che va detta è che a casa nostra ci sono stati sempre molti libri, di tutti i generi, dalle enciclopedie ai libri di storia dell’arte, dalla letteratura alle riviste di architettura e design, fino ai fumetti, naturalmente. Mio padre era appassionato di architettura e arredamento, di cose “moderne” diciamo, mia madre invece aveva una formazione classica, amava la musica sinfonica, le chiese antiche e Ingmar Bergman.

Di chiese antiche e musei ne abbiamo visitati tanti da piccoli, nei viaggi con i genitori, tuttavia, di cose da guardare e assorbire ce n’erano tante in casa. Passavo ore a sfogliare i libri e a “guardare le figure”, tante figure, tantissime (una scoperta continua) e a leggere fumetti come tutti i ragazzini. Credo che la mia passione per le “figure” sia nata proprio grazie ai tanti libri che avevamo, quindi una passione non proprio nata direttamente dalle persone. Tuttavia avevo uno zio e un nonno che dipingevano per hobby, per cui immagino che qualcosa devo avere ereditato. Soprattutto dal punto di vista dell’hobby. A proposito di mio zio, mi ricordo un piccolo quadro che aveva dipinto e che da bambino mi piaceva moltissimo. Era il ritratto di un signore con un’espressione intensa e severa, con la barba e una maglia a strisce. A quel tempo non sapevo chi fosse quel signore e questo fatto di non sapere, questo “enigma”, mi piaceva. Poi molti anni dopo, sempre nei libri, ho scoperto che quel signore era Henri Matisse, copia dell’autoritratto del 1906. Di conseguenza, ho anche capito perché mi piacesse così tanto.

In un libro di storia dell’arte scoprii la Crocefissione di Francis Bacon, accanto a Burri, a Moore, a Giacometti, a Warhol. Mi incantavo, mi piacevano tutti. Erano momenti prossimi alla felicità. Tuttavia non sapevo e non capivo. Non capivo niente. Il punto importante, credo, sta proprio in questo “non capire”. Ti avvicina alle cose in modo diretto, istintivo, primitivo, felice. Ti sembra di vedere ancora più in là, qualcosa di più grande e di straordinario, che probabilmente non esiste. È uno stato emotivo, i primi accenni di spiritualità. Il non capire è una promessa di rivelazione, è il “mistero laico” di Jean Cocteau, è il primo tempo sacro.

G.L.: Hai mai avuto la voglia di impadronirti di queste immagini attraverso il disegno copiandole per farle tue?

R.G.: Sì certo, ma più del desiderio di impadronirmi di un’immagine copiandola, c’era questa innata spinta all’emulazione. A tutt’oggi, quando vedo una cosa che mi piace (un quadro, una scultura, un video, un film, la grafica di un libro), istintivamente mi viene voglia di rifare qualcosa di simile, qualcosa che sia all’altezza, ma a modo mio.

Naturalmente succede molto di rado, ho anche imparato a godermi le cose senza “ansia da prestazione”, tuttavia questa fibrillazione è sempre presente. Senonchè, da ragazzino, leggendo tanti fumetti (supereroi perlopiù) mi veniva voglia di farli anch’io. Ma non li copiavo, li guardavo, li studiavo, poi chiudevo l’albo e iniziavo a disegnare personaggi miei “alla maniera di”. Questo è un metodo che mi veniva naturale, spontaneamente. Credo che sia un buon esercizio per metabolizzare le cose facendole proprie in modo originale, cercando di attingere alle proprie risorse emotive, anche, naturalmente, attraverso la memoria e a quello che ti ispira. Un esercizio tecnico, ma anche un esercizio spirituale.

Poi però, più avanti, ai tempi del liceo, ho iniziato anche a copiare le foto che mi piacevano che trovavo nelle riviste. Le copiavo a matita, nel modo più preciso e analitico possibile (mi ero un po’ fissato con gli iperrealisti). Così ho imparato il chiaroscuro, cosa che non avevo mai imparato e capito copiando dal vero. Ed è a questo punto che arriva il problema: il mio limite a comprendere la realtà che mi circonda. Stavo imparando a capire le immagini e nel frattempo sfuggivo alla comprensione della realtà. La intuivo, appunto, attraverso le immagini. Così ho iniziato a fare le foto con la reflex (altro ottimo esercizio di formazione), foto che poi ridipingevo ad olio. Anche questo è un processo di appropriazione interessante.

G.L.: Quale è stato il tuo iter scolastico? Durante i tuoi studi hai fatto degli incontri con persone che si sono rivelati importanti per i successivi sviluppi del tuo lavoro?

R.G.: Ho fatto il liceo artistico e poi mi sono diplomato allo IED nel corso di grafica. La grafica sarebbe poi diventata il mio lavoro.

Con alcuni compagni di liceo strinsi un’amicizia che, più o meno, dura ancora. Devo dire che sono stato fortunato, diciamo che la mia formazione culturale in senso più contemporaneo (ma non solo), la devo a loro. Erano ragazzi curiosi e intuitivi, più avanti di me. Si parlava di tutto, di arte naturalmente, di cinema, di musica, di libri, di cose nuove. Io ascoltavo e imparavo. C’era sempre qualche nuova scoperta sulla quale dissertare e ragionare. Si parlava di artisti, di persone e di ragazze. Ho imparato molto, ma la cosa più importante è che con loro ho sviluppato una certa sensibilità critica ed estetica rispetto all’arte e, in qualche modo, rispetto alla vita.

E poi, anche se ancora molto giovani, loro avevano già le idee abbastanza chiare: sarebbero diventati artisti, o scrittori, chissà. Così, negli anni dopo il liceo, mi introdussero ai misteri dell’arte contemporanea e conobbi tanti altri artisti, e critici e galleristi, e di conseguenza feci nuove amicizie nell’ambiente romano.

Nel frattempo continuavo a disegnare per me, a fare fotografie, a dipingere un po’. Anche allo IED conobbi persone con cui condividere la passione per la grafica e con le quali iniziai anche a lavorare.

In ogni modo il mio lavoro di grafico si è poi sempre più svolto nel e per il mondo dell’arte contemporanea, dove effettivamente mi sono sentito più di casa, diciamo, essendo ormai avvezzo alla materia. E qui si chiude il cerchio. O un cerchio, non lo so ancora bene.

G.L.: In quegli anni hai mai avuto voglia di fare l’artista anche tu?

R.G.: A dire il vero avevo le idee piuttosto confuse. Sapevo che c’erano delle cose che mi piaceva fare, quindi anche l’idea di fare l’artista non mi dispiaceva. Sapevo di avere talento per il disegno, ma al contempo scoprii di avere anche talento per la grafica (al liceo si faceva qualche lavoro di grafica), per cui un po’ mi immaginavo pittore, un po’ mi immaginavo grafico, un po’ disegnatore di fumetti, un po’ attore comico. Io sono un pigro e quindi fatalista, dunque pensavo sempre “vabbè, vediamo che succede”.

La verità è che il talento non basta, immaginarsi artista non basta, bisogna volerlo veramente, serve consapevolezza. E comunque, in generale, le cose vanno perseguite, ci vuole determinazione, bisogna insistere, altrimenti vuol dire che non sono poi così importanti. Prima lo capisci, meglio è. Ma questi sono ragionamenti fatti col senno di poi, all’epoca non avevo molto il senso dell’orientamento, per così dire.

G.L.: Quindi hai continuato a cullarti in questa indecisione?

R.G.: No no, decisi di fare l’Accademia di Belle Arti, pittura (forse magari senza tantissima convinzione), ma non passai l’esame d’ammissione. Comunque non rimasi ne’ deluso ne’ avvilito, lo considerai come un “episodio possibile” nel normale flusso degli eventi. Avrei potuto ritentare l’anno dopo, ma optai per la grafica. Evidentemente non avevo il cosiddetto fuoco sacro dell’arte. A questo punto potrei citare la famosa frase di John Lennon, ma non lo faccio.

Tuttavia ho continuato a frequentare le amicizie dell’arte, gli studi degli artisti, a vedere le mostre. E a disegnare quando ne avevo voglia, in modo molto libero, sereno. Anche quelli erano momenti prossimi alla felicità. In linea di massima non ho mai più smesso. Senonchè, in anni più recenti, mi sono ritrovato con un corpo di lavoro interessante diciamo, che ho deciso di rendere pubblico (seppure in modo episodico) grazie all’incoraggiamento degli amici.

Insomma, a questa età ho imparato, in linea generale, che una cosa non esclude l’altra, le cose possono coesistere. Tutte le cose. Sembra banale, stupido, ma per me è una piccola rivelazione.

G.L.: Il tuo lavoro d’ artista è sempre andato avanti sul suo binario autonomo rispetto al tuo lavoro con la grafica o ci sono stati dei momenti in cui le due cose hanno coinciso?

R.G.: Ho sempre considerato il fatto di disegnare come momento di assoluta libertà, di libere associazioni, anche di non-sense se vogliamo. Il foglio è lo spazio dove tutto può avvenire. Il disegno è un pensiero anarchico. La grafica ha invece regole precise, si deve adattare al contenuto, è progettuale. Quindi, direi che no, le due cose non hanno mai coinciso realmente, anzi, nel mio caso sono opposte.

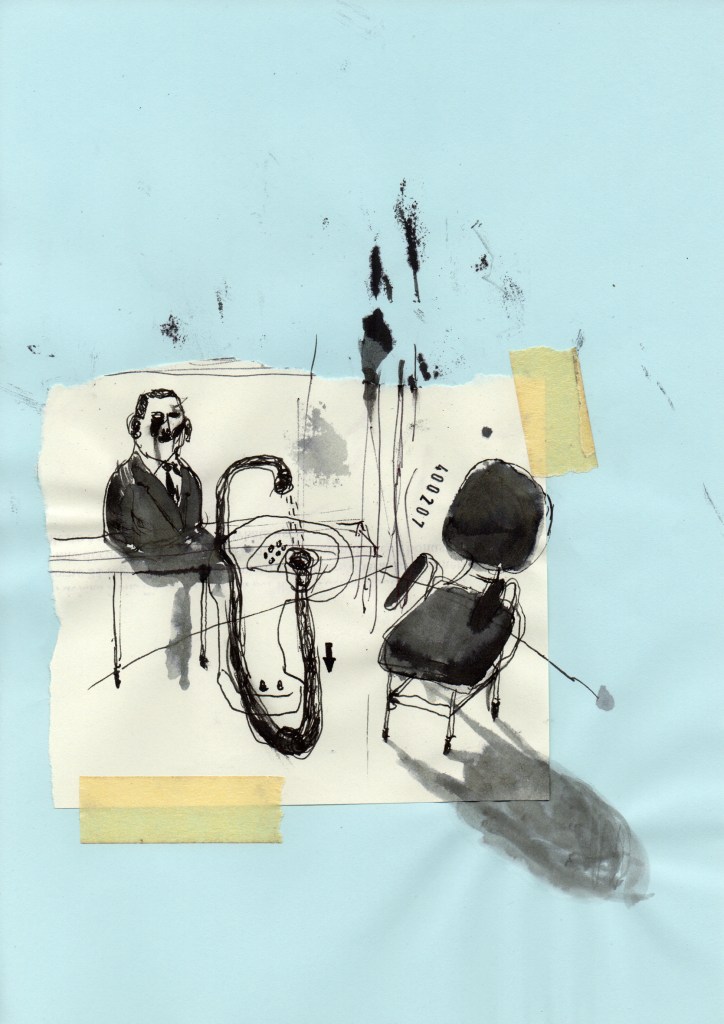

Tuttavia, nei miei disegni, spesso associo alle figure numerazioni o scrittura (senza un vero sistema), che conferiscono al tutto una sembianza di schema, di tavola scientifica, di “figura” da libro. Questo è anche un sistema per “raffreddare” i miei disegni, che spesso sono un po’ crudeli, tragici e buffoneschi. Allora, in questo senso, si può trovare un punto di contatto tra disegno e grafica.

Tra l’altro, negli anni, ho imparato ad apprezzare molto schemi grafici e diagrammi, sia da un punto di vista estetico, sia dal punto di vista del senso, della sintesi. Sono una sorta di poesia visiva. Tanti artisti che mi piacciono hanno lavorato e lavorano al riguardo.

G.L.: Entrando nel merito del tuo lavoro artistico. Hai sempre disegnato in bianco e nero?

R.G.: Sì, più o meno, salvo per qualche scritta o elemento fatti con penne colorate che si vanno a sovrapporre al bianco e nero portante delle figure.

Quello che mi interessa sono il segno, i volumi e la dinamica delle figure. Quindi vado dritto al punto, il colore per me è una distrazione, non mi serve. Mi piace pensare in termini di assoluto. Se penso a un’immagine, la penso in bianco e nero, o comunque monocroma. Inoltre, come mi è già capitato di dire, spesso penso al disegno come scultura nuda e cruda, quindi automaticamente e involontariamente il disegno esce acromatico. In tutta autonomia. È il disegno che pensa di essere, io sono solo il tramite.

G.L.: La scelta di lavorare pricipalmente con la penna a sfera che origine ha?

R.G.: La penna a biro è sempre a portata di mano. Se mi viene in mente una cosa, un’idea, uno scarabocchio, prendo la penna e butto giù velocemente. Poi magari mi fermo, dopo un po’ riguardo, riprendo la penna e qualcosa viene fuori. Per me il senso è molto legato all’estemporaneità e la biro, nella sua semplicità, questo me lo permette. Va anche detto che sono un pigro, dunque semplifico le cose. Potrei usare la matita, ma alla fine è troppo “artistica”, la biro è basica, diretta, comune, e non si può cancellare. Per cui gli errori che vengono fuori restano, (sappiamo come l’incidente in arte sia sempre auspicabile, non si sa dove ti porta, si possono scoprire delle cose). Il fatto di non cancellare, alla fine, è una cosa legata all’onestà credo, al tentativo di essere veri. Naturalmente, oltre alla biro, uso pennello e inchiostro o qualche tempera. Per sbrigarmi anche il caffè e la salsa di soia, insomma quello che trovo al momento. Ma queste cose per me sono già sovrastruttura…

G.L.: Mi piace molto quando dici: “È il disegno che pensa di essere, io sono solo il tramite.” Lo credo anch’io il lavoro quando c’è decide autonomamente il suo compiersi, il nostro ruolo è quello di assecondarlo nel miglior modo possibile prestando attenzione alla sua voce.

Quando inizi a disegnare parti con un’idea precisa di quello che vuoi fare?

R.G.: Qualche volta ho un’idea precisa, la maggior parte delle volte no. Quando ho un’idea precisa, difficilmente il disegno riesce come l’avevo immaginato. Alla fine diventa un’altra cosa, se ne va per conto suo, come dicevamo prima. Ma questo è il bello, non so mai cosa può succedere. A volte mi stupisco di quello che ho fatto, è una bella sensazione. Credo che valga un po’ per tutti gli artisti. Lo stupore è importante.

Più spesso invece, inizio con una figura (per me tutto parte dalla figura umana), poi a mano a mano capisco come andare avanti, oppure mi fermo direttamente lì, decido che va bene. Ultimamente mi affido sempre di più al caso, sperando di fare qualcosa di diverso, ma più che altro mi vengono fuori delle cose senza senso. Non lo so, forse il senso sta proprio nel nonsense, oppure nel caos, nel vuoto metafisico, in questa sorta di teatro dell’assurdo che si autogenera…

G.L.: Prima hai detto che pensi ai tuoi disegni come a sculture, intendi dire che hanno una valenza scultorea in sé o che sono degli appunti per delle possibili sculture che vorresti realizzare?

R.G.: Diciamo entrambe le cose. Quando guardo le figure che disegno, penso che alcune siano delle sculture. Stanno lì isolate, nel vuoto del foglio bianco, presenze o apparizioni nello spazio neutro. Sul foglio, in genere, metto anche l’annotazione “studio per scultura”. Quando guardo le figure di Bacon, ad esempio, penso che siano sculture, o magari quelle di Giotto, sempre per fare un esempio. Le sculture di Giacometti, invece, sono disegni. Vedi come vanno le cose…

Comunque non credo che mi cimenterò mai nella scultura, è già tanto se riesco a disegnarla. Con i miei tempi lunghissimi mi ci vorrebbero almeno tre vite per fare quello che una persona normale fa in una.

Però il pongo mi attira.

G.L.: A proposito di Bacon mi sembra che mel tuo lavoro tu lo tenga molto presente per esempio l’idea della figura ingabbiata.

R.G.: Bacon certo, anche da qui non ne esco, ma va bene così. Più che ingabbiata, direi che la figura è contenuta dalla struttura, è isolata da tutto il resto. È come metterla in una bacheca, sottovuoto, a gravità zero. E sta lì, in esposizione. Tra l’altro il parallelepipedo è un escamotage per mettere la figura in relazione con la superficie e dare tridimensionalità allo spazio che la circonda.

G.L.: In quello che fai l’immaginario cimematografico ha una sua importanza? L’idea per esempio della rappresentazione del movimento, che da secoli gli artisti hanno affrontato in vari modi, che importanza ha per te? Ti volevo anche chiedere se sei mai stato tentato dall’idea di realizzare un film d’animazione partendo dai tuoi disegni?

R.G.: Può darsi che qualche suggestione cinematografica sia entrata nei miei lavori, però, così a occhio, non saprei dirti niente di preciso. Forse c’è una certa idea di dramma in atto, questo sì.

Per quanto riguarda la rappresentazione del movimento (giustamente puntualizzi “rappresentazione”), secondo me ci sono due aspetti fondamentali ed eventualmente separati da considerare. Uno è il dinamismo degli elementi nella stessa rappresentazione; l’altro è la rappresentazione divisa in sequenze.

Il dinamismo è legato alla gestualità, alla visibile velocità esecutiva, all’assetto degli elementi.

Poi c’è la rappresentazione in sequenze di immagini, quindi i polittici, le varie vie crucis, i fumetti. Qui la rappresentazione in movimento è chiaramente narrativa. La cosa interessante è che in tutti e due gli aspetti, attraverso il movimento, vediamo il tempo coagulato in un’unica dimensione.

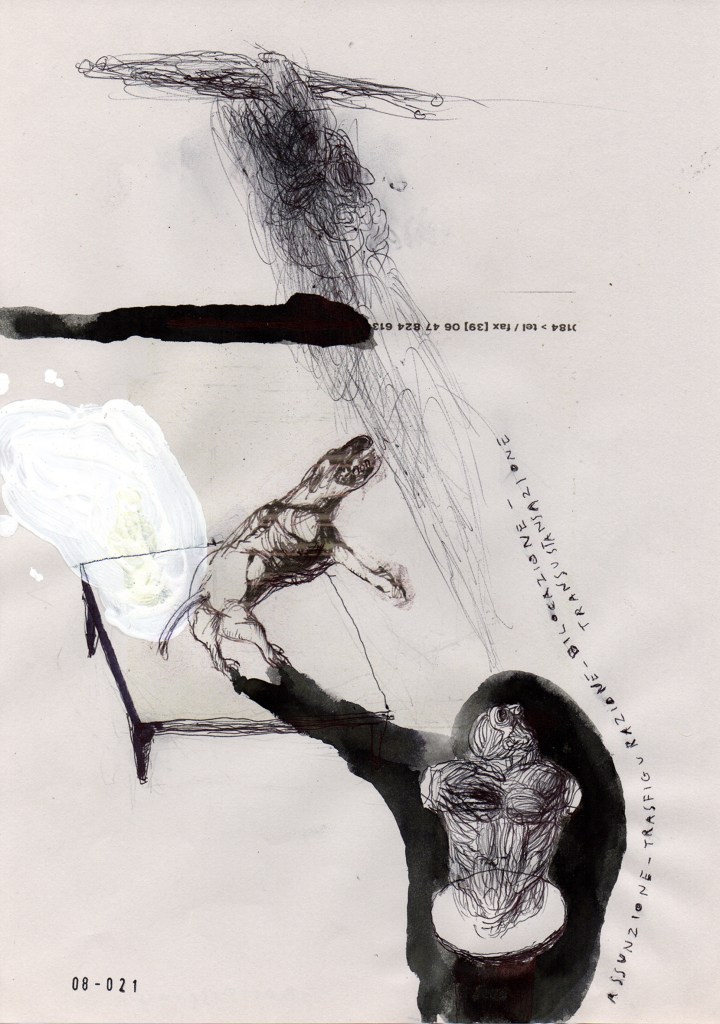

Quando disegno depenso, cerco la figura con la penna e non cancello. Senonchè la figura viene fuori, spesso, da una serie di tentativi (segni) che restano visibili, o da grovigli di segni “furiosi” che coprono gli errori. A volte restano braccia e gambe in più, o in meno. Tutto questo mette la figura in risonanza diciamo, la postura è statica, ma la figura vibra, è in continuo movimento, in uno stato di ansia perpetuo. Implode e poi riesplode. Il tempo così diventa circolare o infinito.

Alcune volte mi sono divertito a disegnare situazioni in sequenza, in sequenze da tre perlopiù.

Ho fatto alcune foto con esposizione lunghissima, dove sullo stesso fotogramma viene impresso il soggetto nei suoi diversi movimenti durante l’esposizione, alla Duchamp per intenderci. Dunque il movimento è importante per me, sia in termini espressivi, sia in termini narrativi, sia in termini di tempo che passa e ritorna su sé stesso.

Questa circolarità mi interessa, il concetto sarebbe da approfondire anche attraverso l’animazione, perché no. Qualche volta ci penso. Avevo fatto delle brevissime animazioni in stop motion con le foto, così, per capire.

G.L.: Con che risultati ?

R.G.: Soddisfacenti dal mio punto di vista e di partenza. Sicuramente non originali, un po’ nonsense (va da sé), un po’ cinema espressionista, un po’ David Lynch.

G.L.: Prima quando ti chiedevo della vicinanza con il cinema pensavo proprio a Lynch che oltre a fare film è artista a tutto tondo. Che importanza ha il suo lavoro per te?

R.G.: David Lynch pittore l’ho scoperto da pochi anni a questa parte e certamente ho trovato delle affinità con quello che faccio. Mi piace molto, ogni tanto mi guardo i suoi lavori. Ultimamente sono diventati una fonte di ispirazione. Alcuni hanno quell’atmosfera cupa e ironica dei suoi

film in cui mi ci ritrovo. Forse non ha un’importanza centrale per me, però è diventato comunque un riferimento.

G.L.: Ho visto che spesso nei tuoi disegni ricorrono delle immagini anatomiche di organi interni del corpo, spesso dell’apparato digerente, che si coniugano a meraviglia con il tuo segno. Che importanza ha la rappresentazione del corpo e della sua caducità nel tuo lavoro?

R.G.: Per me il corpo è la figura, cioè l’immagine assoluta, l’icona, l’unica rappresentazione.

Non esiste liberazione dal corpo; le figure che disegno le vedo spesso prigioniere, o meglio, tombate nel proprio corpo, statue tra vita e morte diciamo. La mia rappresentazione del corpo, anche se può non sembrare, è prima di tutto tragica, e poi comica. Non ne esco, è così. È l’entropia. E così ecco che si mostrano gli organi interni, che alla fine anche di questo siamo fatti.

Gli organi sono belli da disegnare,li invento, seguo la mano, possono diventare un ghirigoro infinito. Decorano la figura con grazia e spavento (per chi guarda e per la figura stessa).

A volte gli organi sono fuori dal corpo, e si mostrano alla figura come un’apparizione.

Deleuze, a proposito di Francis Bacon, parla del “corpo senza gli organi”, non mi dilungo, ma è una cosa importante e assai suggestiva.

G.L.: Esiste nel tuo lavoro un aspetto narrativo?

R.G.: Esiste, sì, in molti casi. Come dicevo prima, inizio disegnando una figura senza sapere bene dove andare a parare, poi ad esempio, aggiungo un tavolo, poi un’altra figura e via dicendo. A questo punto si creano inevitabilmente delle dinamiche, di conseguenza il lavoro diventa narrativo. Ma sono le dinamiche che mi interessano, spesso sono impreviste, abbastanza incomprensibili, non-sense (ed è lì che mi diverto), a volte invece sono volute. Spesso metto due figure una davanti all’altra, speculari, come se una apparisse all’altra. Non sappiamo quale delle due sia l’apparizione, non conosciamo le ragioni dell’evento, e dunque il tentativo è proprio quello di creare una forma di sgomento in chi guarda. Questo è sicuramente voluto, o quantomeno cercato e alla fine diventa un po’ una provocazione. Mi interessa mettere in scena l’evento metafisico: si capisce che sta succedendo qualcosa, ma non si sa bene che cosa e perché. È inconoscibile. In un mondo di arte sempre e comunque spiegata e giustificata, io non so spiegare, non voglio spiegare e non giustifico, io posso solo raccontarvi del fantasma.

G.L.: Riccardo ti é mai venuto a trovare il fantasma delle pittura?

R.G.: Sì, è un fantasma antico quello della pittura, viene da lontano, chissà da dove. Ma più che altro sono stato “visitato” da giovane. Ho dipinto per un po’, poi sono passato al disegno che, come dicevo, è un modo più veloce e meno impegnativo per tirare fuori delle cose. La pittura ha bisogno di tempo e io sono già troppo lento di mio. Quindi ho lasciato che le cose seguissero un loro processo naturale. Ma intendiamoci, non ho rimpianti per questa “incompiutezza”, sono un po’ fatalista e ognuno alla fine è quello che è. Tuttavia, ogni tanto, questo fantasma torna ancora oggi, sotto forma di visioni pittoriche, ma restano delle visioni appunto, restano nella mente, perché altrimenti questo significherebbe ricominciare tutto daccapo. Negli ultimi anni, tra l’altro, il “fantasma” mi appare più sotto forma di scultura che di pittura. Forse la scultura è la vera apparizione, forse disegno sculture che non farò mai.

Per tornare alla pittura, va anche detto che il “quadro” resta sempre un inganno, l’immagine è confinata nei limiti della tela e sul supporto della tela. Anche se parliamo di astrazione o di pittura tra astrazione e figurazione, resta sempre un inganno. Allora mi viene in mente Fontana: se tagli un quadro, il quadro muore, muore l’immagine, sveli il trucco. Se tagli un disegno, lo strappi, lo sporchi, lo rovini, quello comunque resta disegno, anche più bello eventualmente. Perché alla fine il disegno rappresenta sé stesso, non ambisce a essere qualcos’altro, è onesto. Ma non sto qui a fare l’apologia del disegno, in realtà, altrettanto onestamente dovrei dire che l’ideale per me sarebbe quello di disegnare (o eventualmente anche di dipengere) sui muri, senza limiti, senza fine. In questo senso mi interessa molto anche la pittura installativa che interviene nello spazio e lo modifica.

Riccardo Gemma è nato a Roma nel 1963.

È grafico e disegnatore. Dopo il Liceo Artistico si diploma allo IED.

Come grafico lavora da freelance prevalentemente nell’editoria per l’arte contemporanea. Ha collaborato con innumerevoli artisti, gallerie, fondazioni, musei. Tutt’ora, tra gli altri, collabora con il Palazzo delle Esposizioni di Roma e il Maxxi. Ha inoltre progettato e realizzato l’immagine per eventi d’arte contemporanea ed altri eventi istituzionali.

Come artista ha esposto alla Galleria Ugo Ferranti (Roma) nel 2008, all’open studio di Via Portonaccio (Roma) nel 2009, ha partecipato alle rassegne di FourteenArtTellaro (Tellaro, La Spezia) nel 2019 e nel 2022.

English version

Conversation with Riccardo Gemma

#wordartist #interviewartist #riccardogemma

Gabriele Landi: Hi Riccardo, for most artists the first “symptoms” of this serious disease called art manifest themselves in early childhood in most cases unconsciously, sometimes transmitted by more or less close relatives. Did this happen to you as well, tell?

Riccardo Gemma: The first thing that needs to be said is that there have always been a lot of books in our house, of all genres, from encyclopedias to art history books, from literature to architecture and design magazines, to comic books, of course. My father was into architecture and furniture, “modern” things let’s say, my mother on the other hand was classically trained, loved symphonic music, old churches and Ingmar Bergman.

Of old churches and museums we visited many as children, on trips with our parents, however, of things to look at and absorb there were many in the house. I would spend hours flipping through books and “looking at figures,” lots and lots of figures (a constant discovery) and reading comic books like all kids. I think my passion for “figures” came about because of the many books we had, so a passion not really born directly from people. However, I had an uncle and grandfather who painted as a hobby, so I guess I must have inherited something. Especially from the hobby point of view. Speaking of my uncle, I remember a small painting he painted that I loved as a child. It was a portrait of a gentleman with an intense and stern expression, with a beard and a striped shirt. At that time I did not know who that gentleman was, and this fact of not knowing, this “enigma,” appealed to me. Then many years later, again in books, I found out that that gentleman was Henri Matisse, a copy of the 1906 self-portrait. As a result, I also understood why I liked him so much.

In an art history book I discovered Francis Bacon’s Crucifixion, alongside Burri, Moore, Giacometti, Warhol. I was enchanted, I liked them all. They were moments close to happiness. However, I didn’t know and I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand anything. The important point, I think, lies precisely in this “not understanding.” It brings you closer to things in a direct, instinctive, primitive, happy way. You feel like you see even further, something bigger and more extraordinary, which probably doesn’t exist. It is an emotional state, the first hints of spirituality. Not understanding is a promise of revelation, it is Jean Cocteau’s “secular mystery,” it is the first sacred time.

G.L.: Did you ever have a desire to take hold of these images through drawing by copying them to make them your own?

R.G.: Yes of course, but more than the desire to take hold of an image by copying it, there was this innate urge to emulate. To this day, when I see something that I like (a painting, a sculpture, a video, a film, a book graphic), I instinctively want to remake something similar, something that lives up to it, but in my own way.

Of course it happens very rarely, I have also learned to enjoy things without “performance anxiety,” yet this fibrillation is always there. Except, as a kid, reading a lot of comic books (superheroes mostly) made me want to make them too. But I wouldn’t copy them, I would look at them, study them, then close the book and start drawing characters of my own “in the manner of.” This is a method that came naturally to me, spontaneously. I think it is a good exercise to metabolize things by making them your own in an original way, trying to draw on your own emotional resources, also, of course, through memory and what inspires you. A technical exercise, but also a spiritual exercise.

But then, later on, in my high school days, I also started copying pictures that I liked that I found in magazines. I used to copy them in pencil, as precisely and analytically as I could (I got a bit fixated on the hyperrealists). So I learned chiaroscuro, something I had never learned and understood by copying from life. And that’s where the problem comes in: my limitation in understanding the reality around me. I was learning to understand images, and in the meantime I was escaping the understanding of reality. I was intuiting it, precisely, through images. So I started taking pictures with an SLR (another good training exercise), pictures that I would then repaint in oil. This is also an interesting process of appropriation.

G.L.: What was your schooling process? During your studies did you have encounters with people who turned out to be important for the later development of your work?

R.G.: I went to art school and then graduated from IED in the graphic design course. Graphic design would later become my job.

With some of my high school classmates I formed a friendship that, more or less, still lasts. I must say that I was lucky, let’s say that my cultural education in a more contemporary sense (but not only), I owe it to them. They were curious and intuitive kids, ahead of me. We talked about everything, about art of course, movies, music, books, new things. I would listen and learn. There was always some new discovery to dissertate and reason about. We talked about artists, people, and girls. I learned a lot, but the most important thing was that with them I developed a certain critical and aesthetic sensibility with respect to art and, in some way, with respect to life.

And then, although still very young, they already had quite clear ideas: they would become artists, or writers, who knows. So, in the years after high school, they introduced me to the mysteries of contemporary art and I met many other artists, and critics and gallery owners, and as a result I made new friends in the Roman environment.

In the meantime I kept drawing for myself, taking photographs, painting a little bit. Also at IED I met people with whom I shared a passion for graphic design and with whom I also began to work.

In any case, my work as a graphic designer then increasingly took place in and for the contemporary art world, where I actually felt more at home, let’s say, being accustomed to the subject by now. And there it comes full circle. Or a circle, I still don’t really know.

G.L.: Did you ever feel like being an artist yourself during those years?

R.G.: I was actually quite confused about it. I knew there were some things I liked to do, so I didn’t mind the idea of being an artist either. I knew that I had a talent for drawing, but at the same time I discovered that I also had a talent for graphic design (in high school we did some graphic design work), so I kind of imagined myself as a painter, I kind of imagined myself as a graphic designer, I kind of imagined myself as a comic book artist, and I kind of imagined myself as a comic actor. I am a lazy and therefore fatalist, so I always thought “whatever, let’s see what happens.”

The truth is that talent is not enough, imagining yourself as an artist is not enough, you have to really want it, you need awareness. And anyway, in general, things have to be pursued, it takes determination, you have to persist, otherwise it means they are not that important. The sooner you understand that, the better. But these are arguments made in hindsight, at that time I didn’t have much sense of direction, so to speak.

G.L.: So you continued to lull yourself into this indecision?

R.G.: No no, I decided to do the Academy of Fine Arts, painting (perhaps without much conviction, perhaps), but I didn’t pass the entrance exam. However, I was neither disappointed nor disheartened, I regarded it as a “possible episode” in the normal flow of events. I could have tried again the following year, but I opted for graphic design. Evidently I did not have the so-called sacred fire of art. At this point I could quote John Lennon’s famous phrase, but I don’t.

However, I continued to frequent art friendships, artists’ studios, to see exhibitions. And to draw when I felt like it, in a very free, serene way. Those were also moments close to happiness. In principle, I never stopped again. Senonchè, in more recent years, I found myself with an interesting body of work let’s say, which I decided to make public (albeit episodically) thanks to the encouragement of friends.

In short, at this age I have learned, generally speaking, that one thing does not exclude the other, things can coexist. All things. It sounds trivial, stupid, but for me it’s a small revelation.

G.L.: Has your work as an ‘artist always proceeded on its own independent track from your work with graphic design, or have there been times when the two coincided?

R.G.: I have always considered drawing as a moment of absolute freedom, of free associations, even of nonsense if you will. The paper is the space where anything can happen. Drawing is an anarchic thought. Graphics, on the other hand, has precise rules, it has to adapt to the content, it is design. So, I would say that no, the two have never really coincided; in fact, in my case they are opposites.

However, in my drawings, I often associate figures with numbering or writing (without a real system), which give the whole thing a semblance of a scheme, a scientific table, a book “figure.” This is also a system to “cool down” my drawings, which are often a bit cruel, tragic and buffoonish. So, in this sense, you can find a point of contact between drawing and graphic design.

By the way, over the years, I have learned to appreciate graphic diagrams and diagrams a lot, both from an aesthetic point of view and from the point of view of meaning, of synthesis. They are a kind of visual poetry. So many artists I like have worked and are working in this regard.

G.L.: Going into your artwork. Have you always drawn in black and white?

R.G.: Yes, more or less, except for some writing or elements done with colored pens that are superimposed on the black and white bearing of the figures.

What I’m interested in is the mark, the volumes and the dynamics of the figures. So I get straight to the point, color for me is a distraction, I don’t need it. I like to think in terms of the absolute. If I think of an image, I think of it in black and white, or at least monochrome. Also, as I’ve said before, I often think of drawing as bare sculpture, so automatically and unintentionally the drawing comes out achromatic. In all autonomy. It is the drawing that thinks it is, I am just the medium.

G.L.: What is the origin of your choice to work mainly with the ballpoint pen?

R.G.: The ballpoint pen is always at hand. If I come up with something, an idea, a doodle, I pick up the pen and quickly jot it down. Then maybe I stop, after a while I look again, pick up the pen and something comes up. For me, meaning is very much about extemporaneity, and the ballpoint pen, in its simplicity, this allows me to do that. It must also be said that I am a lazy person, so I simplify things. I could use pencil, but in the end it’s too “artistic,” ballpoint pen is basic, direct, common, and you can’t erase it. So the mistakes that come out remain, (we know how accident in art is always desirable, you don’t know where it takes you, you can discover things). Not erasing, in the end, is something related to honesty I think, to trying to be true. Of course, besides ballpoint pen, I use brush and ink or some tempera. To hurry up I also use coffee and soy sauce, in short, whatever I can find at the moment. But these things for me are already superstructure….

G.L.: I really like it when you say, “It is the drawing that thinks it is, I am just the medium.” I believe that too, the work when it is there decides for itself its fulfillment, our role is to go along with it as best we can by paying attention to its voice.

When you start drawing do you start with a clear idea of what you want to do?

R.G.: Sometimes I have a clear idea, most of the time I don’t. When I have a definite idea, the drawing hardly succeeds as I imagined it. Eventually it becomes something else, it goes off on its own, as we said before. But that’s the beauty of it, I never know what can happen. Sometimes I’m amazed at what I’ve done, it’s a good feeling. I think it applies a little bit to all artists. Astonishment is important.

More often, however, I start with a figure (for me everything starts with the human figure), then as I go along I figure out how to go forward, or I stop right there, I decide it’s okay. Lately I’ve been relying more and more on chance, hoping to do something different, but mostly I come up with nonsense. I don’t know, maybe the sense really lies in the nonsense, or in the chaos, in the metaphysical vacuum, in this sort of self-generating theater of the absurd….

G.L.: You said earlier that you think of your drawings as sculptures, do you mean that they have a sculptural value in themselves or that they are notes for possible sculptures that you would like to make?

R.G.: Let’s say both. When I look at the figures I draw, I think some of them are sculptures. They stand there isolated, in the blank of the white paper, presences or apparitions in neutral space. On the paper, I also usually put the note “study for sculpture.” When I look at Bacon’s figures, for example, I think they are sculptures, or maybe Giotto’s, again to give an example. Giacometti’s sculptures, on the other hand, are drawings. You see how things go…

Anyway, I don’t think I’ll ever try my hand at sculpture; it’s bad enough if I can draw it. With my very long times it would take me at least three lifetimes to do what a normal person does in one.

Pongo attracts me, though.

G.L.: Speaking of Bacon it seems to me that mel your work you keep him very much in mind for example the idea of the caged figure.

R.G.: Bacon of course, I don’t get out of that either, but that’s okay. More than caged, I would say that the figure is contained by the structure, it is isolated from everything else. It’s like putting it in a bulletin board, in a vacuum, in zero gravity. And it just sits there, on display. By the way, the parallelepiped is a ploy to relate the figure to the surface and give three-dimensionality to the space around it.

G.L.: In what you do, does cimematographic imagery have an importance? The idea for example of the representation of movement, which artists have dealt with in various ways for centuries, how important is it to you? I also wanted to ask you if you have ever been tempted by the idea of making an animated film from your drawings?

R.G.: It may be that some cinematic suggestion has entered into my works, however, so far as I can tell, I couldn’t tell you anything specific. Maybe there is a certain idea of drama going on, that is.

As for the representation of movement (you rightly point to “representation”), in my opinion there are two fundamental and possibly separate aspects to consider. One is the dynamism of elements in the same representation; the other is the representation divided into sequences.

The dynamism is related to the gestures, the visible speed of execution, the arrangement of the elements.

Then there is the representation in sequences of images, so the polyptychs, the various ways of the cross, the comic strips. Here the moving representation is clearly narrative. The interesting thing is that in both aspects, through movement, we see time coagulated into one dimension.

When I draw I depense, I look for the figure with the pen and do not erase. Senonchè the figure comes out, often, from a series of attempts (marks) that remain visible, or from tangles of “furious” marks that cover mistakes. Sometimes extra arms and legs remain, or less. All this puts the figure in resonance let us say, the posture is static, but the figure vibrates, is in constant motion, in a perpetual state of anxiety. It implodes and then re-explodes. Time thus becomes circular or infinite.

A few times I had fun drawing situations in sequence, in sequences of three mostly.

I have done some photos with very long exposures, where on the same frame the subject is imprinted in its different movements during the exposure, à la Duchamp to be clear. So movement is important to me, both in terms of expression, in terms of narrative, and in terms of time passing and returning on itself.

This circularity interests me, the concept would also be to be explored through animation, why not. Sometimes I think about it. I had made very short stop-motion animations with photos, just to understand.

G.L.: With what results ?

R.G.: Satisfactory from my point of view and starting point. Definitely not original, a little nonsense (goes without saying), a little expressionist cinema, a little David Lynch.

G.L.: Earlier when I was asking you about the closeness to cinema I was just thinking of Lynch, who in addition to making films is a well-rounded artist. How important is his work to you?

R.G.: David Lynch the painter I discovered him a few years ago and certainly found affinities with what I do. I really like him, so I look at his work from time to time. Lately they have become a source of inspiration. Some of them have that dark and ironic atmosphere of his

films that I find myself in. It may not be of central importance to me, however, it has become a reference nonetheless.

G.L.: I’ve seen that anatomical images of internal organs of the body, often of the digestive system, often recur in your drawings, and they go wonderfully with your sign. How important is the representation of the body and its transience in your work?

R.G.: For me the body is the figure, that is, the absolute image, the icon, the only representation.

There is no liberation from the body; the figures I draw I often see as prisoners, or rather, tombed in their own bodies, statues between life and death let’s say. My representation of the body, although it may not seem so, is first of all tragic, and then comic. I don’t get out of it, that’s how it is. It is entropy. And so there you show the internal organs, that in the end that’s what we’re made of as well.

Organs are beautiful to draw,I invent them, I follow the hand, they can become an infinite doodle. They decorate the figure with grace and fright (for the beholder and for the figure itself).

Sometimes the organs are outside the body, showing themselves to the figure like an apparition.

Deleuze, about Francis Bacon, talks about the “body without the organs,” I won’t go into that, but it is an important and very suggestive thing.

G.L.: Is there a narrative aspect in your work?

R.G.: There is, yes, in many cases. As I said before, I start by drawing a figure without really knowing where to go with it, then for example, I add a table, then another figure and so on. At this point, dynamics inevitably arise, consequently the work becomes narrative. But it’s the dynamics that interest me, often they are unexpected, quite incomprehensible, nonsense (and that’s where I have fun), sometimes they are intentional. I often put two figures in front of each other, mirrored, as if one appeared to the other. We don’t know which one is the apparition, we don’t know the reasons for the event, and so the attempt is precisely to create a form of dismay in the viewer. This is definitely intended, or at least attempted, and in the end it becomes a bit of a provocation. I’m interested in staging the metaphysical event: you understand that something is happening, but you don’t really know what and why. It is unknowable. In a world of art always and everywhere being explained and justified, I cannot explain, I do not want to explain and I do not justify, I can only tell you about the ghost.

G.L.: Has Riccardo ever visited you with the ghost of painting?

R.G.: Yes, it is an ancient ghost that of painting, it comes from far away, who knows where. But more than anything else I was “visited” when I was young. I painted for a while, then I switched to drawing, which, as I said, is a faster and less demanding way to get things out. Painting needs time and I am already too slow by myself. So I let things follow their own natural process. But mind you, I have no regrets about this “unfinishedness,” I am a bit of a fatalist and everyone is what they are in the end. However, every now and then, this ghost still comes back, in the form of pictorial visions, but they remain visions precisely, they remain in the mind, because otherwise this would mean starting all over again. In recent years, by the way, the “ghost” appears to me more in the form of sculpture than painting. Maybe sculpture is the real apparition, maybe I draw sculptures that I will never make.

To return to painting, it should also be said that the “painting” always remains a deception, the image is confined within the limits of the canvas and on the canvas support. Even if we talk about abstraction or painting between abstraction and figuration, it always remains a deception. Then Fontana comes to mind: if you cut a painting, the painting dies, the image dies, you reveal the trick. If you cut a drawing, tear it, dirty it, ruin it, that still remains drawing, even more beautiful possibly. Because in the end the drawing represents itself, it does not aspire to be something else, it is honest. But I’m not here making an apologia for drawing, actually, just as honestly I should say that the ideal for me would be to draw (or possibly even to paint) on walls, without limits, without end. In this sense I am also very interested in installation painting that intervenes in the space and modifies it.

Riccardo Gemma was born in Rome in 1963.

He is a graphic designer and draftsman. After art high school he graduated from the IED.

As a graphic designer he works freelance mainly in publishing for contemporary art. He has collaborated with countless artists, galleries, foundations, museums. He still collaborates with the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome and the Maxxi, among others. He has also designed and created the image for contemporary art events and other institutional events.

As an artist, he exhibited at Galleria Ugo Ferranti (Rome) in 2008, at the open studio in Via Portonaccio (Rome) in 2009, and participated in the FourteenArtTellaro exhibitions (Tellaro, La Spezia) in 2019 and 2022.