#paroladartista #intervistaartista #gabrielemallegni

▼scroll down for text in English

Gabriele Landi: Ciao Gabriele, accade spesso che i primi sintomi del manifestarsi di una appartenenza all’arte risalgano alla prima infanzia è stato così anche per te? Racconta?

Gabriele Mallegni: Credo proprio di si, non so bene codificare quale sia stato al livello cronologico l’inizio dei primi sintomi, ma penso che sia stato il periodo fra la fine della scuola materna e le elementari. Mi è sempre piaciuto disegnare, (questo lo dicono i miei genitori), ma anche smontare gli oggetti e i giocattoli per capirne il funzionamento (logicamente poi dopo il mio trattamento non funzionavano pìù).

Ricordo un un fatto accaduto in prima elementare che influenzò molto la mia immaginazione e la mia tendenza per la materia e il volume. La maestra chiese alla classe di disegnare degli animali che avevamo visto liberi nella natura. Poche settimane prima i miei genitori mi avevano portato nel Parco di San Rossore a Pisa e avevo visto per la prima volta un cervo. Ne rimasi molto colpito, quindi decisi di disegnarlo, fu una delle prime restituzioni di una immagine mentale a un immagine bidimensionale su carta. Mi piaceva, ero contento. Un po’ meno quando tutto felice portai il disegno alla maestra. Non appena lo vide sgranò gli occhi dicendomi davanti a tutta la classe che un cervo con le corna verdi non esisteva. Da quel momento capii di essere daltonico. Ci fu un goffo tentativo da parte di mia madre di farmi sentire meno a disagio comprandomi le matite colorate con su scritto il nome del colore, ma fu tutto inutile, io vedevo in un altro modo, la mia percezione era quella, e ogni tentativo o sforzo di uniformarmi al vedere come gli altri risultò un fallimento.

A quel punto non mi arresi, cambiai i soggetti. A metà degli anni 80 uscirono un sacco di films di fantascienza e io ne rimanevo molto affascinato, le astronavi, l ‘ignoto, lo spazio , un immaginario a me sconoscito ma fortemente attraente. Incominciai così a disegnare le astronavi, in genere bianche o grigie con le lucine gialle o arancioni, così avevo aggirato il problema del colore.

Fu anche il periodo in cui scoprii il pongo, materiale plastico, modellabile, di vari colori. Mi resi conto rapidamente che mischiandoli tutti insieme si otteneva una massa di colore unico molto scuro, un colore incodificabile, senza un nome specifico. Ecco a quel punto scoprii la mia predilezione per il modellato, dare forma con le proprie mani a figure che popolavano la mia mente, forme instabili che potevano essere plasmate e rimodellate in un ciclo continuo e infinito.

Secondo me essere daltonico mi ha portato a sviluppare una sensibilità per la luce, nel senso di come la luce comunica con i volumi, come li sfiora e come li rivela a seconda dell’inclinazione, basta un minimo cambio di intensità che il volume cambia, e devo dire che questa cosa la ritrovo anche nella percezione del tutto personale che ho nei confronti del colore, non riesco mai a dare un nome pecifico a quello che vedo, se cambia anche di poco la luce io vedo un altro colore, totalmente diverso da quello che avevo percepito con un altra luce.

Se dovessi ricercare i primi sintomi di un’appartenenza all’arte, e in maniera più specifica alla scultura, li collocherei proprio in quel momento.

G.L.: Che iter scolastico hai seguito e quali incontri, se ci sono stati, si sono rivelati importanti per te?

G.M.: Ho frequentato il Liceo Artistico Statale di Lucca agli inizi degli ani 90, non se attualmente sia organizzato così, ma al tempo, una volta arrivati al secondo anno bisognava scegliere fra la sezione Architettura, che ti avrebbe permesso di entrare senza esame di ammissione alla facoltà, e la sezione Accademia attraverso cui poter accedere senza esame all’Accademia di Belle Arti. Non avendo le idee molto chiare scelsi di fare la sezione Architettura, ma dopo un anno passai alla sezione Accademia, diplomandomi al quarto anno e iscrivendomi l’anno successivo all’Accademia di belle Arti di Carrara.

Fu sicuramente una scelta instintiva, legata più alle amicizie a cui tenevo che a una scelta consapevole e ponderata, ma pensandoci con il senno di poi sono contento di averla fatta, mi dette modo di vedere due aspetti e due modi di affrontare le cose, uno più pragmatico e organizzato, l’altro più libero e meno sottoposto a regole e schemi matematici.

Ebbi però la fortuna che in entrambe le sezioni insegnava un professore che è stato fondamentale per la mia crescita, non solo artistica ma anche umana. Si chiamava Ezio Grida. Era un professore di plastica, uno scultore di altri tempi con una conoscenza dei materiali e delle tecniche notevole. Il primo impatto con lui non fu facile, era una persona molto nervosa e un po’ burbera, con uno sguardo profondo e penetrante che metteva soggezione. La prima lezione ci fece trovare su un piccolo piedistallo una natura morta composta da delle bottiglie e una mela. Ci disse che dovevamo disegnarla su un piano di creta per poterla riprodurre in bassorilievo. Per me non fu facile, una cosa era disegnarlo, un compromesso grafico bidimensionale, altra cosa era riuscire a capire i piani, la prospettiva, gli oggetti in primo piano e quelli in secondo. Con un po’ di fatica ci riuscii, il secondo step fu il ritratto di profilo di un compagno di classe sempre in bassorilievo. Capii subito che quello che avevo appreso dalla natura morta fu fondamentale per il successivo ritratto.

Incominciai ad appassionarmi alla materia e Ezio se ne accorse. A quel punto ci propose il ritratto di un compagno questa volta però a tutto tondo. Ezio aveva un modo tutto suo di spiegare le cose, un metodo poco convenzionale che ai tempi di oggi farebbe drizzare i capelli a qualsiasi docente. Passava intorno ai cavalletti con gli occhiali sulla punta del naso e scrutava con gli occhi attenti quello che facevamo. Spesso capitava di rimanere in un punto morto, davanti alla figura che non riusciva a prendere forma, lisciando con le dita i piani incerti, fossilizzanosi su un unico punto di vista. A quel punto Ezio interveniva, metteva le mani sul lavoro, con colpi precisi e ben assestati, spesso anche con una stecca, cambiava i connotati alla figura, quella stessa figura che avevi davanti da ore ma che non progrediva, bastavano due gesti e due parole fondamentali “deve girare” oltre a una serie di improperi e di offese che però erano una suo modo di volerci bene. Con il tempo ho capito la scultura grazie a lui, a non fermarsi ad un unico punto di vista , lo scorrere dei volumi, la luce.

Una persona unica che sono contento di avere incrociato in quel momento importante e di formazione della mia vita.

Un altro incontro fondamentale è stato quello con l’artista Caterina Sbrana, mia attuale compagna di vita e di lavoro con la quale abbiamo fondato Sudio17.

Ci siamo conosciuti all’Accademia di belle Arti di Carrara molto giovani e dal quel momento siamo sempre stati insieme, abbiamo condiviso tanta vita aiutandoci e condividendo molte esperienze, momenti difficili, momenti belli, che ci hanno fatto crescere e che spero che ci faranno crescere ancora.

La passione e la sensibilità con cui affronta il proprio lavoro e quello comune è stata per me molto importante. La sua sensibilità peculiare, il suo punto di vista, il confronto tra i nostri percorsi di formazione così diversi, mi hanno aiutato ad essere più riflessivo più attento e meno distruttivo sia sul lavoro che nella vita in generale, stemperando il mio lato nichilista senza però forzare la mano riuscendo a capire le differenze caratteriali che abbiamo.

G.L.: All’Accademia che indirizzo hai scelto?

G.M.: Ho scelto l’indirizzo scultura con il Prof. Piergiorgio Balocchi, un docente che mi ha sempre lasciato libero di sperimentare assecondando la mia ricerca.

G.L.: Dopo gli studi come si è evoluto il tuo lavoro?

G.M.: Negli ultimi anni in cui frequentavo l’Accademia incominciai ad usare nella mia ricerca il ferro e materiali di scarto industriali con i quali costruivo grandi insetti o aracnidi, fu per me una specie di terapia , che non è servita ad un granchè, dato che sono fortemente aracnofobico tuttora, il riprodurli ed esaminarli da vicino o sulle riviste mi faceva illudere di averne meno paura. Agli inizi usavo anche materiali di recupero, molto influenzato da quello che fu e che è tuttora è il movimento Mutoid Waste Company. Frequentavo assiduamente un centro sociale a Pisa che si chiamava Macchia Nera, una bizzara forma di esperimneto sociale anarchico e caotico, dove noi adolescenti del luogo sguazzavamo fra concerti e spettacoli (fra l’altro in questo centro sociale hanno suonato gruppi di tutte le parti del mondo magari ancora poco conosciuti ma che di lì a poco sarebbero diventati icone del rock indipendente al livello mondiale). Io da ragazzo rimasi molto colpito dal movimento Mutoid, mi attirava l’atmosfera post-apocalittica, il caos e l’uso dei rottami con i quali creavano enormi robots semoventi tutto condito con musica techno autoprodotta.

Giravano in carovane, con furgoni assemlbati, colorati e polverosi sempre accompagnati da un forte odore di benzina e gasolio che impreganava la loro pelle e i loro vestiti. Una parte di una carovana rimase stanziale al Macchia Nera per alcuni anni. Fu un esperienza molto formativa, ma ben presto incominciai a non usare più materiali di recupero, perché la loro forma mi condizionava e mi distraeva dalle forme che invece avrei voluto ottenere. Infatti incominciai a lavorare da un fabbro, dove mi perfezionai nella tecnica della saldatura e nella progetttazione, mi fu molto utile anche per la mia ricerca artsistica disciplinandomi dandomi un approccio meno caotico a quello che stavo facendo. Incominciai così ad usare il ferro in un altra maniera, assemblavo profilati che in genere si usano per fare cancelli, inferriate ecc, creando snodi , articolazioni, che mi permisero di ottenere grandi strutture leggere e mobili, integrando il ferro anche con il legno in maniera da ottenere forme autoportanti che si adattavano in qualsiasi spazio perché cambiavano di forma e di dimensione. Grandi artropodi in continua evoluzione, cambiando pezzi, sostituendoli con altri.

Nello stesso periodo collaboravo con l’Università di Pisa nel campo delle ricostruzioni fisiognomiche mediante l’uso dei parametri della medicina legale, modellavo volti da reperti ossei, ottenendo fisionomie con un alta percentuale di attendibilità (dal 70 % all’ 80%). Fu molto interessante ma ovviamente molto lontano dal lavoro creativo.

Successivamentee ho lavorato per alcuni anni da un restauratore di mobili antichi, dove ho imparato l’uso di vari materiali che non avevo conosciuto ancora durante il mio percorso, anche qui ero lontano dal lato creativo ma mi è risultato importantissimo per la conoscenza delle tecniche. La materia e la conoscenza tecnica sono per me fondamenteli per la mia ricerca personale.

Intanto il progetto di avere uno studio proprio insieme a Caterina si stava facendo sempre più reale, infatti dopo qualche anno fondammo Studio17, il nostro laboratorio di ricerca dove più tardi scoprimmo la ceramica e ci appassionammo talmente tanto da usarla tutt’ora nel nostro lavoro, sia personale che comune.

G.L.: Come è avvenuto l’incontro con la ceramica e in che cosa l’uso di questo materiale si è rilevato importante per lo sviluppo del tuo lavoro?

G.M.: Ho iniziato ad avvicinarmi alla ceramica circa 10 anni fa. Avendo una formazione da scultore

ho sempre avuto un contatto diretto con le materie plastiche, ma usavo la creta o la plastilina essenzialmente per modellare, una volta finito il lavoro non facevo altro che formarlo, nel senso che tramite gomme siliconiche o calchi a forma persa riportavo il modello dal materiale plastico e quindi ancora duttile, allo stato solido, usando quindi gesso, resine ecc. Mi accorsi però che in questi pasaggi si perdevano gran parte dei segni e delle impronte che venivano impresse sulla materia ancora morbida durante la fase di modellatura.

Il passaggio alla ceramica è stato molto naturale, mi ha affascinato il fatto che molte tecniche che si usano nella scultura potevano essere applicate alla ceramica, tecniche come la formatura si confacevano alla lavorazione della terra sempre tenendo presente vari acorgimenti che ho imparato con il tempo. Ho trovato interessante il fatto di riuscire ad ottenere un “pezzo unico”, finito e praticamente indistruttibile (a meno che non venga fatto cadere o sollecitato violentemente). Il passaggio da uno stato malleabile che permette un infinita possibilità di variazioni consentendo ripensamenti, distruzioni e rigenerazioni continue, a quello solido ottenuto dopo la cottura che lo fissa al suo stato finale, pressochè eterno e incorruttibile. Un altro fattore che mi ha suscitato entusiasmo è il passaggio molto diretto dal pensiero astratto che avevo nella mente, riportato tramite le mani, a qualcosa di concreto. Un materiale che consente molti ripensamenti ma che allo stesso tempo per la sua natura instabile prima della cottura, esige una disciplina, un’attenzione ai tempi sia di lavorazione che di essicazione. Il mondo della ceramica è molto vasto, credo che una sola vita non basti per apprendere le innumerevoli tecniche e discipline che la caratterizzano, in questo senso mi sento ancora in una fase di apprendimento, di scoperta. Dalla scelta della terra stessa, ai colori e alle infinite finiture che possono cambiare totalmente l’esito del lavoro finale. Un materiale sensibile al tocco, all’aria, alle tensioni, sia in fase di asciugatura che di cottura, un materile usato dall’uomo fin dagli albori della sua storia Se ci pensiamo molti manufatti fittili risalenti ad un passato remoto sono arrivati a noi come esempio della sua importanza in tutta la storia umana. E’ quindi un materiale antichissimo e allo stesso tempo moderno, che per sua bellezza e funzione, non è ancora stato soppiantato da altri materiali sintetici e di nuova generazione. La ceramica è ovunque e usata per moltissimi scopi, è prosaica come un wc, e allo stesso tempo può trascendere in un opera d’arte.

G.L.: Ti succede spesso di avere dei ripensamenti o di distruggere quello su cui stai lavorando?

G.M.: Un tempo mi succedeva spesso, ora invece tendo piuttosto ad abbandonare il lavoro senza distruggerlo, perchè ho imparato dopo un sacco di lavori perduti che è sempre meglio averli, sia come archivio personale, sia come spunto per altri lavori. Mi capita spesso di riuscire a risolvere un problema tecnico o concettuale quando meno me lo aspetto, quando sto pensando ad altro, in altri contesti, in un altro tempo. Questa è una preogativa del mio metodo di lavoro, se sono troppo coinvolto, se la mia attenzione è troppo focalizzata rischio di non trovare la soluzione che immancabilmente arriva in maniera totalmente disattesa.

G.L.: Che rapporto esiste tra il tuo lavoro e la dimensione temporale?

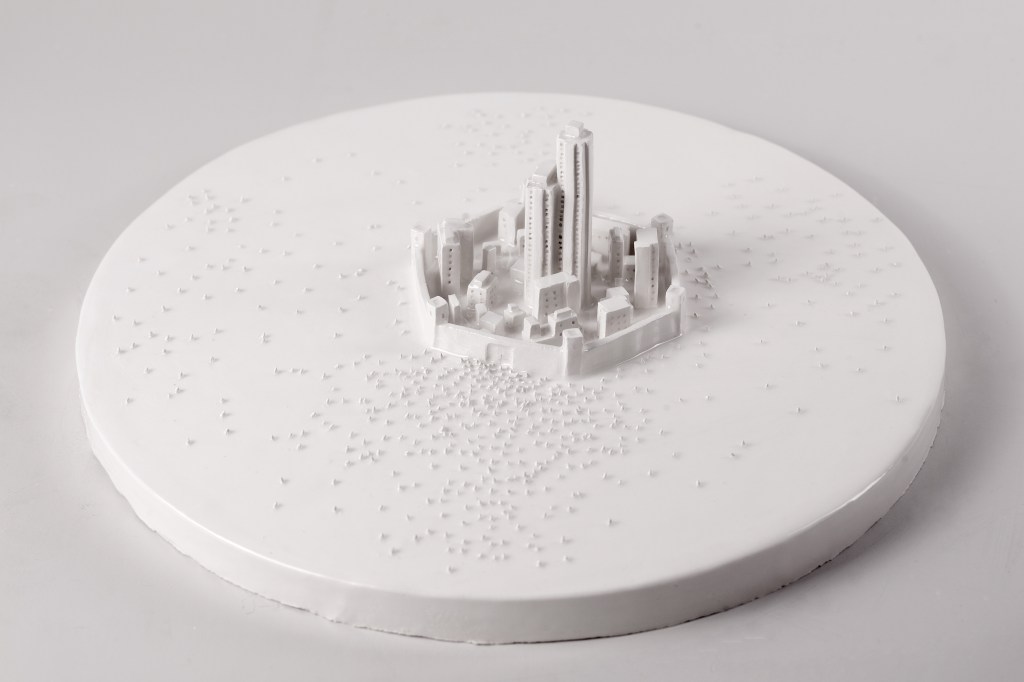

G.M.: Ho incominciato ad interessarmi del tempo e dell’ effetto che ha sulle cose che ci circondano da qualche anno. Intorno al 2016 nacque “Opera catasrofica in tre atti”, ( Mutabilia, Paratissima, Torino 2016) un lavoro in terra cotta . Tre moduli della stessa dimensione , tre sequenze di uno storyboard, modellate in modo urgente e fresco come un bozzetto. Nel primo elemento la città va a fuoco, nel secondo l’entropia si fa strada fra le rovine della città che mantiene sempre la stessa pianta . L’ ultima visione è la città distrutta avvolta dalla vegetazione, dove un piccolissimo cane in cima ad un palazzo osserva dall’alto le rovine decadenti ma vive di quella che fu una volta una moderna e fiorente città.

Le rovine, i segni e le tracce delle civiltà che ci hanno preceduto mi hanno sempre affascinato, percepirne la grandezza, lo sviluppo e l’inevitabile decadimento per me è molto affascinante, ci ricorda che nonostante la potenza, la grandezza e le conoscenze tecniche avanzate, tutte le civilltà del passato sono decadute, per periodi lunghissimi dimenticate, e successivamente riscoperte. Un passaggio inevitabile e inesorabile, che si ripete da sempre e per sempre si ripeterà. Sono molto appassionato di letteratura fantascientifica e di cinematrografia, e mi ha sempre colpito come l’uomo sia riuscito a modificare e a evolversi sul lato filosofico e tecnico in così breve tempo, un tempo infinitesimale rispetto alle ere geologiche e ad altri abitanti della terra che ci hanno preceduto come i dinosauri vissuti per milioni di anni. Dal 2019 a ora sono nati altri lavori riguardo al tempo, “Living remains I e II, un opera in continua evoluzione, in cemento grigio, edifici dove quotidianamente e incessantemente cadono gocce d’acqua. Nel corso del tempo il muschio ha ricoperto gli edifici, un lavoro in continua mutazione fatto di muschio, acqua, cemento e tempo (opera esposta a Roma alla Galleria 28, Piazza di Pietra durante la mostra dei finalisti di Malamegi Prize Lab 19). Un ultimo lavoro che vorrei citare sono le “Clessidre”, lavoro sempre in ceramica dove piccoli soggetti architettonici o modelli in scala di automobili si presentano nel loro momento di massimo splendore, ma capovolgendole come una clessidra, il lato sottostante ci mostra lo stesso soggetto ma mutato e consumato dal passaggio del tempo.

G.L.: La ceramica bianca smaltata, che spesso usi nei tuoi lavori, si porta dietro una tradizione che rimanda subito a certi manufatti di grande diffusione popolare (le ceramiche di Capodimonte per esempio). Mi sembra di leggere fra le righe nel tuo lavoro una volontà di voler ironizzare con la tradizione che questa tecnica si porta dietro. A tale proposito ti volevo chiedere di parlare delle Punkette.

G.M.: Si, in effetti la vena ironica non manca. Anche se nel caso specifico delle Punkette userei il termine “trasposizione”, nel senso che non ho fatto altro che cambiare i soggetti dei busti della ceramica popolare fra 1700 e 1800 con soggetti contemporanei. Al posto di ritratti di giovani donne del passato ritratte alla moda dell’epoca le ho modernizzate sostituendole con giovani donne dei nostri tempi e quindi con pettinature punk, piercing, collari chiodati e altri particolari che appartengono al nostro presente. Quello che però ho cercato di fare è di rendere la stessa raffinatezza e delicatezza delle manifatture del passato. Da scultore sono sempre stato affascinato dal bel modellato di certe opere, dalla profonda conoscenza anatomica, dalla precisione tecnica di cui erano padroni gli scultori del passato, quindi in questi lavori ho cercato di mantenere una certa sensibilità e un attenzione al dettaglio senza però scadere nel kitsch (spero di esserci riuscito) perché scadere nel volgare e nel trash è un attimo in certe operazioni. Ancora una volta l’esperienza manifatturiera, il saper fare e il buongusto della tradizione si confermano un ottimo strumento per veicolare temi e pratiche contemporanee. In fondo è un operazione molto semplice, a volte guardando films in costume dove i personaggi sono truccati e vestiti a seconda dell’epoca in cui è girata la storia, per esempio una Cleopatra interpretatata da Liz Taylor nel 1963 da vita un personaggio storico esistito più di 2000 anni fa, quindi con un minimo sforzo di immaginazione, togliendole il trucco e gli abiti di scena potrebbe essere una ragazza qualsiasi che aspetta il tram mandando foto su whatsupp ad una amica del suo ultimo tatuaggio ai tempi nostri.

G.L.: Esiste nel tuo lavoro un attenzione agli aspetti politici e sociali?

G.M.: Negli ultimi anni il mio lavoro tende ad esaminare questi aspetti. Credo che l’ umanità abbia imboccato una strada molto pericolosa. Sono stato bambino negli anni 80, di conseguenza sono cresciuto vedendo molti cartoni animati giapponesi fra i quali esisteva un filone catastrofista, immaginari post-qualcosa, un evento che sconvolge, la vita che si interrompe per rinascere in altro modo, sopravvissuti, rovine , relitti. Tutto un immaginario che mi ha segnato. Esisteva già la premonizione del disastro di una presa di coscienza che la direzione presa avrebbe portato a qualcosa di inevitabile, un evento o una serie di eventi a catena che avrebbero sconvolto la vita sulla terra.

A confermare il tutto nel 1986 l’incidente di Chernobyl, avevo 9 anni, mi ricordo bene quel senso di spaesamento, certe raccomandazioni da parte degli adulti, l’ ansia strisciante , la paura di qualcosa che non si poteva né vedere né toccare.

Vedendo come stanno andando le cose nel presente, penso che il pronostico fosse stato anche troppo ottimista. L’aumento esponenziale della popolazione con il conseguente consumo di risorse sempre meno reperibili, continenti che fino a 20 anni fa vivevano in condizione di povertà e che ora giustamente reclamano la loro fetta di benessere dopo essere stati sfruttati per secoli porterà a un inevitabile collasso. E’ tutto sotto i nostri occhi, sta avvenendo anche più rapidamente di quello che avevamo previsto. Pur tuttavia non stiamo facendo nulla perché questo possa essere evitato, basta guardarsi intorno anche nel locale, non è necessario osservare gli scenari globali, continuiamo a costruire, cementificare, tombare fiumi ecc, senza nemmeno fare caso a quello che già esiste, a quello che potrebbe essere recuperato. Tutto questo in nome di uno sviluppo e una crescita legata al benessere di pochi e al malessere molti, rincorrendo il Pil, indicatore del tutto forviante.

Capisco che potrei essere tacciato di pessimismo, non credo di esserlo, alla luce dei fatti mi definirei realista, perché penso che l’ottimismo in funzione del marketing sia uno dei fenomeni più devastanti.

Gabriele Mallegni (Pisa, 1977) frequenta il liceo Artistico a Lucca, prosegue i suoi studi all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara dove si laurea in scultura con il prof.Giorgio Balocchi.

La sua ricerca si concentra sulla ceramica con la quale modella ritratti contemporanei, mondi distopici, incubi e contraddizioni della società attuale. Il suo immaginario attinge alla science fiction sia dal punto di vista cinematografico che letterario e dall’arte antica. Il suo lavoro indaga il passaggio del tempo, il decadimento delle cose, il rapporto dell’uomo con gli spazi naturali e artificiali.

Nel 2021 vince con l’opera Living remains il Malamegi Lab19.

Vive e lavora a Pisa dove insieme a Caterina Sbrana, fonda nel 2009 Studio17, laboratorio di ricerca per l’arte e il design

Partecipa a simposi e mostre tra le quali ricordiamo: L’estate più fredda, a cura di Claudio Cosma, Sensus luoghi per l’arte contemporanea, Firenze, 2023; Mimesis, Galerie Territoires Partages, Marseille, 2023; Malamegi Lab19, 2022, Galleria Piazza di Pietra fine Art, Roma; XV Bienal Internacional de Ceramica de Aveiro; BACC, la forma del vino, 2021, menzione speciale della giuria, Scuderie Aldovrandini, Frascati, Roma; La natura delle cose, a cura di Mauro Lovi, Palazzo Malpigli , Lucca; Osmosi, a cura di Mauro Lovi, 2017; Duo, Otto Luogo dell’arte Firenze, e Mutabilia, Paratissima Torino, 2016.

Vive e lavora a Pisa dove insieme a Caterina Sbrana, fonda, nel 2009, Studio17, laboratorio di ricerca d’arte e design.

English text

Interview with Gabriele Mallegni

#wordadartist #interviewartist #gabrielemallegni

Gabriele Landi: Hi Gabriele, it often happens that the first symptoms of the manifestation of a belonging to art date back to early childhood, was it like that for you too? Tell us.

–

Gabriele Mallegni: I think so, I don’t really know what the chronological beginning of the first symptoms were, but I think it was the period between the end of nursery school and primary school. I always liked to draw (my parents said so), but I also liked to take objects and toys apart to understand how they worked (logically, they no longer worked after my treatment).

I remember something that happened in first grade that greatly influenced my imagination and my tendency for matter and volume. The teacher asked the class to draw some animals that we had seen free in nature. A few weeks earlier, my parents had taken me to the San Rossore Park in Pisa and I had seen a deer for the first time. I was very impressed by it, so I decided to draw it, it was one of the first returns of a mental image to a two-dimensional image on paper. I liked it, I was happy. A little less so when all happy I took the drawing to the teacher. As soon as she saw it she widened her eyes and told me in front of the whole class that a deer with green antlers did not exist. From that moment I realised I was colour-blind. There was a clumsy attempt on my mother’s part to make me feel less uncomfortable by buying me coloured pencils with the name of the colour written on them, but it was all in vain, I saw in another way, that was my perception, and any attempt or effort to conform to seeing like the others was a failure.

At that point I did not give up, I changed subjects. In the mid-1980s, a lot of science-fiction films came out and I was very fascinated by them, spaceships, the unknown, space, an imaginary world unknown to me but very attractive. So I started drawing spaceships, usually white or grey with little yellow or orange lights, so I got around the problem of colour.

It was also the period when I discovered pongo, a plastic, mouldable material of various colours. I quickly realised that when you mixed them all together you got a mass of one very dark colour, an unmouldable colour, without a specific name. That is when I discovered my predilection for modelling, giving shape with my own hands to figures that populated my mind, unstable shapes that could be moulded and reshaped in a continuous and infinite cycle.

In my opinion, being colour-blind has led me to develop a sensitivity to light, in the sense of how light communicates with volumes, how it touches them and how it reveals them depending on the angle, all it takes is the slightest change in intensity for the volume to change, and I must say that I also find this in my very personal perception of colour, I can never give a specific name to what I see, even if the light changes a little, I see another colour, totally different from what I had perceived in another light.

If I had to look for the first symptoms of belonging to art, and more specifically to sculpture, I would place them right there.

G.L.: What schooling did you follow and what encounters, if any, were important for you?

G.M.: I attended the Liceo Artistico Statale in Lucca at the beginning of the 1990s, I don’t know if it is currently organised that way, but at the time, once you got to the second year, you had to choose between the Architecture section, which would have allowed you to enter without an entrance exam to the faculty, and the Academy section through which you could enter the Accademia di Belle Arti without an exam. Not having very clear ideas, I chose to do the Architecture section, but after a year I switched to the Academy section, graduating in the fourth year and enrolling the following year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara.

It was certainly an instinctive choice, linked more to the friendships I cherished than to a choice. It was certainly an instinctive choice, linked more to the friendships I cherished than to a conscious and pondered choice, but thinking about it with hindsight I am glad I made it, it gave me the opportunity to see two aspects and two ways of approaching things, one more pragmatic and organised, the other freer and less subject to mathematical rules and schemes.

I was fortunate, however, that in both sections a teacher taught who was fundamental to my growth, not only artistic but also human. His name was Ezio Grida. He was a professor of plastics, a sculptor from another era with a remarkable knowledge of materials and techniques. The first impact with him was not easy, he was a very nervous and somewhat gruff person, with a deep and penetrating gaze that was awe-inspiring. The first lesson he had us find on a small pedestal a still life composed of bottles and an apple. He told us that we had to draw it on a clay surface in order to reproduce it in bas-relief. It was not easy for me, one thing was to draw it, a two-dimensional graphic compromise, another thing was to be able to understand the planes, the perspective, the objects in the foreground and those in the background. With some effort I succeeded, the second step was a profile portrait of a classmate, also in bas-relief. I soon realised that what I had learnt from still life was fundamental for the next portrait.

I began to get passionate about the subject and Ezio realised this. At that point he proposed a portrait of a comrade, but this time in the round. Ezio had his own way of explaining things, an unconventional method that in today’s times would make any teacher’s hair stand on end. He would walk around the easels with his glasses on the tip of his nose and scrutinise what we were doing with his watchful eyes. He would often stand at a standstill, in front of the figure that failed to take shape, smoothing the uncertain planes with his fingers, fossilising on a single point of view. At that point Ezio would intervene, he would put his hands on the work, with precise and well-aimed blows, often even with a splint, he would change the features of the figure, that same figure that you had had in front of you for hours but that was not progressing, all it took was two gestures and two basic words ‘it must turn’ in addition to a series of insults and insults that were, however, his way of loving us. With time I understood sculpture thanks to him, not to stop at a single point of view, the flow of volumes, the light.

A unique person that I am happy to have crossed paths with at that important and formative time in my life.

Another fundamental meeting was with the artist Caterina Sbrana, my current life and work partner with whom we founded Sudio17.

We met at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara when we were very young and since then we have always been together, we have shared a lot of life helping each other and sharing many experiences, difficult moments, beautiful moments, which have made us grow and which I hope will make us grow again.

The passion and sensitivity with which he approaches his work and the work we do together has been very important to me. His peculiar sensitivity, his point of view, the comparison between our very different backgrounds, have helped me to be more reflective, more attentive and less destructive both at work and in life in general, softening my nihilistic side without forcing my hand by being able to understand the character differences we have.

G.L.: At the Academy, which course did you choose?

G.M.: I chose the sculpture course with Prof. Piergiorgio Balocchi, a teacher who always left me free to experiment, supporting my research.

G.L.: After your studies, how did your work evolve?

G.M.: In my last years at the Academy, I began to use iron and industrial waste materials in my research, with which I built large insects or arachnids; it was a kind of therapy for me, which didn’t do much good, since I am strongly arachnophobic to this day, reproducing them and examining them up close or in magazines made me believe I was less afraid of them. In the early days I also used recycled materials, much influenced by what was and still is the Mutoid Waste Company movement. I assiduously frequented a social centre in Pisa called Macchia Nera (Black Spot), a bizarre form of anarchic and chaotic social experiment, where we local teenagers wallowed in concerts and shows (among other things, bands from all over the world played in this social centre, perhaps still little known but which would soon become icons of independent rock at world level). As a boy, I was very impressed by the Mutoid movement, I was attracted by the post-apocalyptic atmosphere, the chaos and the use of scrap metal with which they created enormous self-propelled robots, all seasoned with self-produced techno music.

They travelled in caravans, in colourful, dusty vans always accompanied by a strong smell of petrol and diesel that permeated their skin and clothes. Part of one caravan remained stationed at the Black Spot for a few years. It was a very formative experience, but I soon began to stop using recycled materials, because their shape conditioned me and distracted me from the forms I wanted to achieve. In fact, I started working at a blacksmith’s, where I perfected my welding technique and design, which was also very useful for my artistic research, disciplining me and giving me a less chaotic approach to what I was doing. I began to use iron in a different way, assembling profiles that are generally used to make gates, gratings, etc., creating joints, articulations, which allowed me to obtain large light and mobile structures, integrating iron with wood so as to obtain self-supporting forms that could adapt to any space because they changed shape and size. Large arthropods constantly evolving, changing parts, replacing them with others.

At the same time, I was collaborating with the University of Pisa in the field of physiognomic reconstructions using forensic parameters, modelling faces from bone remains, obtaining physiognomies with a high percentage of reliability (70% to 80%). It was very interesting but obviously a long way from creative work.

Afterwards I worked for a few years at an antique furniture restorer, where I learnt the use of various materials that I had not yet known during my career, again I was far from the creative side but it was very important for my knowledge of techniques. The material and technical knowledge are fundamental for me in my personal research. In the meantime, the project of having our own studio together with Caterina was becoming more and more real. In fact, after a few years we founded Studio17, our research workshop where we later discovered ceramics and became so passionate about it that we still use it in our work, both personal and communal.

G.L.: How did your encounter with ceramics come about and in what way did the use of this material prove important for the development of your work?

G.M.: I started approaching ceramics about 10 years ago. Having trained as a sculptor

I have always had direct contact with plastic materials, but I used clay or plasticine essentially for modelling, and once I had finished the work, all I did was shape it, in the sense that by means of silicone rubbers or lost-form casts I brought the model from the plastic material, and therefore still ductile, back to the solid state, using plaster, resins, etc. I realised that these pastures were not very easy to use, but that they were not very easy to make. I realised, however, that in these steps a large part of the marks and impressions that were impressed on the still soft material during the modelling phase were lost.

The transition to ceramics was very natural, I was fascinated by the fact that many techniques used in sculpture could be applied to ceramics, techniques such as shaping were suited to working with earth, always bearing in mind various tricks I learnt over time. I found it interesting that I was able to obtain a ‘single piece’, finished and practically indestructible (unless it is dropped or violently stressed). The transition from a malleable state that allows for an infinite possibility of variations, permitting continuous rethinking, destruction and regeneration, to the solid state obtained after firing that fixes it in its final, almost eternal and incorruptible state. Another factor that aroused my enthusiasm was the very direct transition from the abstract thought I had in my mind, brought back through my hands, to something concrete. A material that allows for a lot of rethinking, but at the same time, due to its unstable nature before firing, requires discipline, attention to processing and drying times. The world of ceramics is very vast, I believe that one lifetime is not enough to learn the countless techniques and disciplines that characterise it, in this sense I still feel I am in a learning, discovery phase. From the choice of the clay itself, to the colours and infinite finishes that can totally change the outcome of the final work. A material that is sensitive to touch, to air, to tensions, both during drying and firing, a material used by man since the dawn of its history If we think about it, many clay artefacts dating back to the remote past have come down to us as examples of its importance throughout human history. It is therefore an ancient yet modern material that has not yet been superseded by other synthetic and newer materials due to its beauty and function. Ceramic is everywhere and used for many purposes, it is as prosaic as a toilet, and at the same time it can transcend into a work of art.

G.L.: Do you often have second thoughts or destroy what you are working on?

G.M.: It used to happen to me a lot, but now I tend to abandon work without destroying it, because I have learnt after a lot of lost work that it is always better to have it, both as a personal archive and as a starting point for other work. I often manage to solve a technical or conceptual problem when I least expect it, when I am thinking about something else, in other contexts, at another time. This is a preogative of my working method, if I am too involved, if my attention is too focused, I run the risk of not finding the solution, which invariably arrives in a totally unattended manner.

G.L.: What relationship exists between your work and the temporal dimension?

G.M.: I started being interested in time and the effect it has on the things that surround us a few years ago. Around 2016, “Opera catasrofica in tre atti” ( Mutabilia, Paratissima, Turin 2016) a work in terra cotta was born. Three modules of the same size, three sequences of a storyboard, modelled as urgently and freshly as a sketch. In the first element, the city is on fire, in the second, entropy makes its way through the ruins of the city, which always retains the same plan. The last vision is the destroyed city shrouded in vegetation, where a tiny dog atop a building watches from above the decaying but living ruins of what was once a modern, thriving city.

The ruins, signs and traces of the civilisations that have gone before us have always fascinated me, to perceive their grandeur, development and inevitable decay is very fascinating to me, it reminds us that despite their power, greatness and advanced technical knowledge, all past civilisations have decayed, for very long periods forgotten, and later rediscovered. An inevitable and inexorable transition, which has been repeating itself forever and will forever be repeated. I am very fond of science-fiction literature and cinematography, and it has always struck me how man has managed to change and evolve on the philosophical and technical side in such a short time, an infinitesimal amount of time compared to the geological eras and other inhabitants of the earth that preceded us such as the dinosaurs that lived for millions of years. From 2019 to now, other works about time have emerged, ‘Living remains I and II, an evolving work in grey concrete, buildings where drops of water fall daily and incessantly. Over time, moss has covered the buildings, an ever-changing work made of moss, water, cement and time (work exhibited in Rome at Galleria 28, Piazza di Pietra during the exhibition of Malamegi Prize Lab 19 finalists). One last work I would like to mention are the “Hourglasses”, a work again in ceramic where small architectural subjects or scale models of cars are presented in their moment of maximum splendour, but by turning them upside down like an hourglass, the side underneath shows us the same subject but mutated and consumed by the passage of time.

G.L.: The white glazed ceramic, which you often use in your work, carries with it a tradition that immediately recalls certain popular artefacts (Capodimonte ceramics, for example). I seem to read between the lines in your work a desire to be ironic with the tradition that this technique carries with it. In this regard, I wanted to ask you about Punkette.

G.M.: Yes, indeed, the ironic vein is not lacking. Although in the specific case of the Punkette I would use the term “transposition”, in the sense that all I have done is change the subjects of busts of popular ceramics between 1700 and 1800 with contemporary subjects. Instead of portraits of young women of the past portrayed in the fashion of the time, I modernised them by replacing them with young women of our times and therefore with punk hairstyles, piercings, studded collars and other details that belong to our present. What I have tried to do, however, is to render the same refinement and delicacy as the workmanship of the past. As a sculptor, I have always been fascinated by the beautiful modelling of certain works, by the profound anatomical knowledge, by the technical precision of which the sculptors of the past were masters, so in these works I have tried to maintain a certain sensitivity and attention to detail without, however, lapsing into kitsch (I hope I have succeeded) because lapsing into the vulgar and trashy is a moment’s notice in certain operations. Once again, manufacturing experience, know-how and the good taste of tradition prove to be an excellent tool for conveying contemporary themes and practices. After all, it is a very simple operation, sometimes looking at costume films where the characters are made up and dressed according to the era in which the story is filmed, for example a Cleopatra played by Liz Taylor in 1963 gives life to a historical character who existed more than 2000 years ago, so with a minimum effort of imagination, removing her make-up and stage clothes she could be any girl waiting for the tram sending photos on whatsupp to a friend of her latest tattoo in our times.

G.L.: Is there a focus on political and social aspects in your work?

G.M.: In recent years, my work tends to examine these aspects. I believe that humanity has taken a very dangerous path. I was a child in the 1980s, consequently I grew up watching a lot of Japanese cartoons in which there was a catastrophist strand, post-event imagery, an event that upsets, life that is interrupted to be reborn in another way, survivors, ruins, wrecks. All imagery that marked me. There was already a premonition of the disaster of a realisation that the direction taken would lead to something inevitable, a chain event or series of events that would disrupt life on earth.

This was confirmed by the Chernobyl accident in 1986, I was 9 years old, I remember well that sense of disorientation, certain recommendations by adults, the creeping anxiety, the fear of something you could neither see nor touch.

Seeing how things are going in the present, I think the prediction was even too optimistic. The exponential increase in population with the consequent consumption of resources that are less and less available, continents that until 20 years ago lived in poverty and are now rightly claiming their share of wealth after having been exploited for centuries will lead to an inevitable collapse. It is all before our eyes, it is happening even faster than we predicted. Yet we are doing nothing to prevent this, we only have to look around even in the local, we do not need to look at global scenarios, we continue to build, cement, bury rivers, etc., without even paying attention to what already exists, to what could be recovered. All this in the name of development and growth linked to the well-being of a few and the malaise of many, chasing after GDP, a totally misleading indicator.

I understand that I could be accused of pessimism, I don’t think I am, in light of the facts I would call myself a realist, because I think that optimism as a function of marketing is one of the most devastating phenomena.

Gabriele Mallegni (Pisa, 1977) attended art school in Lucca, continued his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara where he graduated in sculpture with Prof. Giorgio Balocchi.

His research focuses on ceramics with which he models contemporary portraits, dystopian worlds, nightmares and contradictions of today’s society. His imagery draws on science fiction from both film and literature and ancient art. His work investigates the passage of time, the decay of things, and man’s relationship with natural and artificial spaces.

In 2021 he won the Malamegi Lab19 with his work Living remains.

He lives and works in Pisa where, together with Caterina Sbrana, he founded Studio17, a research laboratory for art and design, in 2009.

He has taken part in symposia and exhibitions including: L’estate più fredda, curated by Claudio Cosma, Sensus luoghi per l’arte contemporanea, Florence, 2023; Mimesis, Galerie Territoires Partages, Marseille, 2023; Malamegi Lab19, 2022, Galleria Piazza di Pietra fine Art, Rome; XV Bienal Internacional de Ceramica de Aveiro; BACC, la forma del vino, 2021, special mention of the jury, Scuderie Aldovrandini, Frascati, Rome; La natura delle cose, curated by Mauro Lovi, Palazzo Malpigli , Lucca; Osmosi, curated by Mauro Lovi, 2017; Duo, Otto Luogo dell’arte Florence, and Mutabilia, Paratissima Turin, 2016.

He lives and works in Pisa where, together with Caterina Sbrana, he founded Studio17, an art and design research laboratory, in 2009.