(English version available)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #lauraviale

▼scroll for English version

Gabriele Landi: Ciao Laura, per molti artisti l’età dell’oro coincide con l’infanzia. È in questa fase della vita che prendono il via una serie di dinamiche che poi si rivelano fondanti della propria identità artistica. È stato così anche per te? Racconta.

Laura Viale: Senza approccio analitico, ma con l’aiuto di un sogno fatto qualche giorno fa, provo a raccontare luoghi, circostanze, atmosfere che sicuramente hanno contribuito a formare la mia persona e la mia pratica artistica.

L.V.: Sono con Christoph, mio marito, nella casa dei miei genitori a Forno Canavese. La casa è là dove ancora si trova e con le sembianze che aveva quando ci vivevamo, ma è anche un galeone.

Siamo in mansarda nello studio dei mei, e ci affacciamo dall’apertura che guarda sul soggiorno al piano di sotto. Ai muri sono appese le stuoie dei nomadi iracheni e i quadri di alcuni amici torinesi, davanti c’è la parete-finestra aperta sul giardino e sulla valle sotto il Monte Soglio.

Dobbiamo andare a Torino da mia mamma e mi preparo per andarci con la casa-nave.

Eccomi dunque a poppa della casa, nel piccolo giardino retrostante l’altra parete-finestra, per mollare le cime d’ormeggio.

Sono al contempo nel castello del veliero. Stiamo partendo, tengo il timone e intanto, dato che il battello è anche una casa in muratura, dietro le finestre inizia lentamente a scorrere il paesaggio.

A questo punto penso che sia più semplice andare a Torino in macchina o in autobus e ri-ormeggiare la casa-nave là dov’era.

In ordine di apparizione:

Forno Canavese, in provincia di Torino, è il paese d’origine della famiglia di mia madre. Nei primi anni ’70 i miei genitori, giovani architetti, vi progettarono e poi costruirono con una coppia di amici una casa, dove ho vissuto dalla terza elementare alla terza media. Ma fin da piccolissima ho passato molto tempo a Forno con mia nonna e mia prozia. Il paese non è precisamente un luogo bucolico. Ha vissuto un boom industriale, con immigrazione da est e sud Italia, poi una grande depressione. In questo senso, e in miniatura, una parabola simile a quella torinese.

Ma Forno si trova in cima a una valle ai piedi delle Alpi, è circondato da boschi pieni di rocce e torrenti, e magnifiche baite di montagna all’epoca già in gran parte abbandonate. Ho giocato molto nel bosco, costruendo postazioni tra alberi, pietre e ruscelli.

Le stuoie dei nomadi iracheni sono parte degli oggetti e delle storie che hanno accompagnato la mia infanzia.

Non ci sono mai stata, ma in effetti sono made in Iraq. Subito dopo la laurea i miei genitori hanno lavorato due anni alla missione archeologica italiana di Baghdad. Facevano i rilievi di antichi castelli e fortezze nel deserto, quando il vento liberava temporaneamente le rovine dalla sabbia. Grazie a un errore di calcolo sono arrivata prima di quanto immaginassero e hanno deciso di farmi nascere in Italia.

Torino è e resta la mia città, dove sono nata e ho vissuto – tranne alcune parentesi – fino a dieci anni fa.

La Torino della mia infanzia era un luogo in cui vari personaggi della cultura e dell’arte, poi diventati parte della storia, si incontravano in piola (il nome torinese per vineria) o venivano a cena a casa. Ad esempio Carol Rama e il suo amico e gallerista Giancarlo Salzano, o Aldo Mondino di cui amavo molto le scarpe bicolore e gli eleganti gessati. Ma anche molti altri… Noi vivevamo con Andrea Bruno, l’architetto che ha restaurato il castello di Rivoli e con cui spesso i miei hanno collaborato, e la sua famiglia. Con i suoi figli siamo rimasti fratelli. Un altro pezzo integrante del mio habitat di quegli anni era la militanza politica dei miei e di tanti altri loro amici, a volte condivisa con gli ambienti culturali cittadini, altre meno. In entrambi quei mondi si passava parecchio tempo tra noi bambini, che godevamo di molta autonomia. E infatti in quegli anni sono nate anche altre fratellanze, tutte ancora oggi pezzi fondamentali della mia famiglia.

Ma trascorrevo anche molto tempo da sola, dopo la scuola andavo spesso nello studio dei miei, che condividevano lo spazio con un gruppo di colleghi e una coppia di illustratori. Li c’erano sempre tanti libri per bambini e pure altre riviste del tempo, da Linus ad Alter Alter, per citarne una che leggevo fin dai tempi dell’asilo! Ma soprattutto, aspettando di andare casa, in studio disegnavo, disegnavo e disegnavo.

Non mi addentro nelle interpretazioni simboliche del galeone. Però poppe, cime, ormeggi, insomma il mare, mi permettono di forzare un poco il racconto per arrivare a un pezzo della mia età dell’oro che nel sogno non c’era.

Mio padre amava moltissimo il Mediterraneo e in particolare la Sicilia. Nel 1969, con un gruppo di amici, che poi erano anche i colleghi di studio, comprò una casa a Filicudi… Per ben un milione di Lire diviso in sei! Frequento l’isola da allora, avevo poco più di un anno. Ci andavamo d’estate, a Natale e a Pasqua. Arrivarci era un vero viaggio, e per me ogni volta anche un rito d’iniziazione dovuto al mal di mare. Poi però me la scialavo, come si dice da quelle parti. Esploravo in totale libertà rocce di mille colori e di mille forme; campi abbandonati pieni di grano solo da poco non più curato, e di viti che ancora davano piccoli grappoli; ruderi in cui a volte trovavo persino piatti e pentole. Per non parlare dei frammenti di vasi e di punte d’ossidiana che dopo la pioggia affioravano qua e là.

L’isola è un po’ cambiata da allora… Di lei continuo ad amare soprattutto la natura selvaggia, aspra, e forte.

Tornando alla tua domanda, le mie parole raccontano di un’abitudine fin da bambina a “frequentare” natura e artificio, di una relazione diretta e fisica con il pianeta ma anche di un approccio contemplativo al mondo.

In effetti, anche quando si presenta in forma particolarmente astratta, il mio è sostanzialmente un lavoro en plein air. La natura – nelle sue più minime espressioni urbane così come in luoghi selvaggi – è sempre il punto di partenza dei miei progetti, alla ricerca di spazi di possibile intersezione tra ambiente esterno e mondo interiore. Che si tratti di disegno, fotografia, o altre vie espressive, è un processo volto a rilevare tracce, piuttosto che a marcare con la propria impronta. E di fatto, giocando con le parole, più o meno direttamente ho partecipato a parecchi rilievi durante tutta la mia infanzia.

G.L.: Ho letto la tua risposta e mi ci sono sentito dentro, grazie Laura. Ora ti chiedo di provare a percorrere un altro pezzo di strada. Come procede la tua formazione che studi hai fatto dopo le scuole medie? Ci sono stati degli incontri che ritieni importanti in questo periodo?

L.V.: Provando a reimmergermi per un momento nel mio sentire di adolescente penso che in quel periodo ho vissuto (quasi) tutto e tutti come incontri importanti. E forse pure dopo, almeno per un bel po’.

Comunque, per il liceo si torna in città. I miei mi propongono il linguistico in favore di una formazione a largo spettro, io non oppongo resistenza. Nel tempo libero lavoro in studi di architettura e soprattutto dagli autori di libri per bambini Lastrego & Testa. A diciott’anni inizio a pubblicare delle mie illustrazioni per alcune riviste.

Siamo negli anni 80. La mia generazione cresce tra il retaggio degli anni di piombo e il grigiore della FIAT, dei suoi turni che determinano l’atmosfera di tutta la città, e del suo indotto, che all’epoca comprende quasi tutto. La militanza politica che ha coinvolto i ragazzi dei decenni precedenti non ci corrisponde più. Forse da tutto ciò ha origine l’intenso clima underground della Torino di quell’epoca, dalla musica a tutte le arti. Al liceo incontro Elisa Sighicelli e con lei Francesco Bernardelli. Siamo sempre insieme a serate e concerti ma ci interessa anche l’arte contemporanea, che per me resta ugualmente una frequentazione familiare e condivisa con parte delle fratellanze.

Sono anche anni di incontri importanti con altri mondi. D’estate sono “in famiglia” in Francia, Inghilterra e California per praticare le lingue che studio a scuola. E con i miei viaggiamo in India, in Cina e Tibet, poi in Yemen. Più tardi continuerò a viaggiare, da sola e con amici.

Scrivendoti realizzo che, curiosamente, le residenze d’artista che ho fatto tanti anni dopo sono state quasi negli stessi luoghi di quei soggiorni per approfondire le lingue straniere.

Dopo due anni di Lettere e Filosofia, a cui m’iscrivo sempre per via del largo spettro, finiti i corsi e gli esami che più mi interessano capisco che è giunta l’ora di studiare quello che davvero vorrei fare. Che a quel tempo è illustrare libri e riviste. Così tra la fine degli anni 80 e l’inizio dei 90 frequento lo IED a Milano. Le esperienze già fatte in quel campo mi permettono fin dal primo anno di iniziare anche a lavorare come autrice, per poi intraprendere a tutto tondo l’attività di illustratrice e grafica per diverse case editrici. E specialmente per Stampa Alternativa di Marcello Baraghini, con la collana di libri Millelire.

In quegli anni inizio anche ad avvicinarmi come artista alle “belle arti” – che prima ho sempre guardato come osservatrice – con episodi sporadici e con gli strumenti per me più a portata di mano, quelli delle mie illustrazioni.

Un evento personale e totale, la morte improvvisa di mio padre, mi sconvolge e al contempo rende urgente un cambio o meglio un ampliamento di prospettiva. Che dal punto di vista artistico si traduce in un primo approccio al paesaggio, adottando una macchina fotografica come strumento per un’indagine velatamente ironica sulla ricerca di empatia con la natura.

Ettore Sottsass, che ho conosciuto per preparare una serie di suoi Millelire e con cui ci si frequenta molto in quel periodo, m’impresta una delle sue Hasselblad per queste prime esplorazioni.

Ne scaturiscono alcune serie di lavori che vengono notati da un amico appassionato d’arte e giovane collezionista, Massimo Sterpi. Grazie a lui e a Elisa poco dopo incontro Guido Carbone, che decide di esporre uno dei miei lavori nello studio della sua galleria. Da quel momento, pur continuando a lavorare con grafica e illustrazione, entro a tempo piuttosto pieno nella pratica artistica e dopo circa un anno esordisco da Guido con la personale If You Lived Here You’d Be Home by Now.

In questo racconto non può essere tralasciata un’altra importante vicenda personale. Dopo questa prima mostra, insieme all’intesa professionale con Guido nasce il legame sentimentale che ci unirà per otto anni.

G.L.: Di che anni stiamo parlando e che clima si respirava a Torino?

L.V.: Siamo alla fine degli anni 90. Soprattutto nella seconda parte di quel decennio, Torino sfida la crisi della FIAT cercando e investendo in nuove o ritrovate vocazioni, tra cui primeggiano arte e cultura. La città che prende forma è diversa da quella della mia adolescenza. Lo testimoniano, tra l’altro, un centro storico rinnovato e gentrificato nelle sue parti popolari ancora ben radicate a fine anni 80, e gli innumerevoli dehors e locali sparsi un po’ ovunque e gremiti di gente: un’assoluta novità per i torinesi, inimmaginabile qualche anno prima.

In questa atmosfera prendono corpo molteplici iniziative piccole e grandi, pubbliche e private, di cui molte legate alla giovane creatività. Inoltre nasce e cresce Artissima, forse la prima fiera italiana a promuovere la partecipazione di gallerie straniere e soprattutto di giovani gallerie. Pochi anni dopo arriveranno le Luci d’Artista. La pubblica amministrazione crea anche programmi per sostenere l’arte giovane, episodi circoscritti rispetto a ciò che avviene in altri paesi, ma comunque fatti concreti e nuovi. Questo processo rinfresca decisamente il clima culturale di Torino, che si presenta al 2000 come la città italiana dell’arte contemporanea.

Personalmente, io respiro aria buona e stimolante tra vecchie conoscenze e nuovi incontri. Certo, per dirla tutta, le residenze d’artista all’estero e lavorare anche oltre i confini cittadini, con Giancarla Zanutti a Milano e Andrew Mummery a Londra, giovano altresì ai miei polmoni.

Ma torniamo a Torino.

Rispondendo alla tua prima domanda ho accennato ad alcuni artisti di altre generazioni. Voglio parlare della mia iniziando con la sorella più sorella delle mie fratellanze. Maria Bruno, alias Sister Flash, dai primi anni 90 street artist e raver. Lei costeggia saltuariamente il “mondo dell’arte”. Ma il suo spirito fluido racconta molto delle tante e preziose interazioni tra diversi contesti umani e culturali nella Torino di cambio millennio; che per Maria continueranno ben oltre, fino al 2016, quando vola in cielo proprio nel tempo di un flash.

Poi ci sono gli artisti che in quel periodo lavorano con Guido Carbone, con i quali siamo in famiglia. Nascono legami per me importanti, tra gli altri con Mario Consiglio, Francesco Lauretta, Maurizio Vetrugno, Monica Carocci. E oltre la galleria, con le artiste Maria Bruni (quasi omonima di Maria Bruno), Maura Banfo, Giulia Caira; Luisa Perlo, Giorgina Bertolino, Francesca Comisso e Lisa Parola del collettivo curatoriale a.titolo; i collezionisti Memo Basso e Ernesto Alessio; Guido Costa, Luca Beatrice, Alberto Peola, Alvise Chevallard di Arte Giovane… Un elenco incompleto di amicizie che, dove possibile, permangono.

In un breve flusso di ricordi inevitabilmente in difetto filologico, e limitandomi agli artisti, nella mia Torino dell’arte di quel tempo ci sono anche Pierluigi Pusole (che peraltro con Guido ha lavorato a lungo), Daniele Galliano, Enrica Borghi, Botto e Bruno, Bartolomeo Migliore, Marzia Migliora, Saverio Todaro, Nicus Lucà, Paolo Piscitelli, Paolo Leonardo, Paolo Grassino… Per citare solo in piccola parte le persone in carne ed ossa che hanno nutrito un humus frizzante e fermentante, a cui poi, con il passare degli anni e per chi non era lì in quel momento, restano associati solo pochi nomi.

A questo punto vorrei parlare di Guido, anche se per me resta materia delicata… Mi affido alle parole di Luca Beatrice nel libro in sua memoria, quando parla degli anni di cui sopra: «In questi anni Guido stesso affronta una significativa trasformazione: da gallerista tende a trasformarsi in “producer”. Con l’artista che lo incuriosisce, sempre che vi siano una stima intellettuale e una complicità, Carbone instaura un dialogo serratissimo che spesso porta a cambiare le carte in tavola, se non a modificare radicalmente i piani.»1

In effetti questo approccio lui lo aveva un po’ con tutti e tutto, direi pure con sé stesso. Credo sia soprattutto per questo che con gli artisti con cui lavorava, ma anche con collezionisti e curatori, si creavano spesso delle vere e proprie amicizie, con tutto ciò che ne poteva conseguire.

Insieme percorriamo pressoché in simbiosi gli anni di cui sto raccontando. Poi improvvisamente Guido si ammala, si capisce che il tempo davanti è poco. Forse proprio per questa ragione lui, sebbene sempre più stanco, non accenna a smettere di lavorare. Mi è chiaro che la cosa più importante per me è condividere con lui questo tempo, e lo facciamo come abbiamo sempre fatto, intersecando sentimenti, lavoro, progetti, curiosità – e anche la malattia. Sono tre anni intensissimi. Lascia questo mondo nel 2006, neanche due giorni dopo aver inaugurato in galleria The Humanist di Bob & Roberta Smith.

Ora, sembrerebbe che questa mia storia sia scandita dagli incontri con la morte. Anche, si, ma io non sono un caso eccezionale. A certi punti succede. Pezzi di te importantissimi partono per sempre, decretando dei “prima” e dei “dopo” assoluti. E anche generando, in qualche modo, più vite all’interno di una stessa esistenza…

G.L.: In quegli anni che lavoro facevi?

L.V.: In quegli anni lavoro molto con la fotografia, al crepuscolo o durante la notte. Esploro ambienti naturali apparentemente remoti, ma spesso dietro l’angolo di casa, attraverso l’ampliato spettro luminoso del paesaggio contemporaneo, dove i colori della luce artificiale si mescolano ai colori “fatti” di materia.

Con lunghe esposizioni, luci colorate trovate o aggiunte ai luoghi in cui mi trovo danno origine a serie che propongono gli stessi dettagli fotografati con diversi colori, “catalogati” poi nei titoli con i numeri dei colori pantone. Lavorando in analogico e en plein air, produco immagini che sono “virtuali” non più di quanto le possa definire come “differenti percezioni del reale”.

Considero la fotografia una pratica contemplativa. Così come lunghe esposizioni permettono all’obiettivo di rilevare ciò che con i nostri occhi a volte si vede, ma spesso non si trattiene, fotografare consente allo sguardo qualche secondo in più rispetto al tempo che abitualmente gli accordiamo. Il risultato è un’immagine che a sua volta può invitare alla contemplazione.

G.L.: Come mai ha scelto di lavorare con la fotografia?

L.V.: Macchine fotografiche in casa ce ne sono sempre state, l’accesso era libero e, credo per i miei dieci anni, ho ricevuto in regalo una piccola automatica tutta per me. Fin da molto giovane ho scattato fotografie, per esplorazioni domestiche, nei viaggi, poi a volte anche per il lavoro di grafica.

Quando mi sono avvicinata alle “belle arti” ero affascinata, tra gli altri, da artisti che negli anni 80 avevano iniziato a usare il mezzo fotografico in modo non documentario, dalla scuola di Dusseldorf a Jeff Wall o Richard Prince, per citarne alcuni.

Ho iniziato a lavorare con la fotografia soprattutto per una necessità quasi fisiologica di “guardare fuori”, di (re)incontrare il mondo. Ossia, di cercare un nuovo punto d’incontro tra me e il mondo.

Tra acquerelli, acrilici, linoleografie e quant’altro dava forma a copertine di libri e illustrazioni, peraltro con soddisfazione, l’obiettivo fotografico si è offerto come la finestra attraverso cui inquadrare porzioni di “realtà” dove il mio occhio potesse vagare.

Ripensandoci, l’incontro con i colori “fatti” di luce e un uso decisamente empirico del mezzo hanno schiuso delle componenti del mio approccio creativo che si ritrovano in tutti i miei lavori successivi, qualunque sia la via espressiva che utilizzo. Ad esempio la mescolanza tra “oggettivo” e soggettivo; il fattore accidentale; l’idea di opera come soglia, punto d’incontro tra dentro e fuori ma anche luogo privo di riferimenti narrativi, aperto alla percezione e all’immaginazione di chi lo osserva.

G.L.: In questo punto di incontro fra te e il mondo l’idea di luogo/paesaggio/cartografia sono categorie che indaghi?

L.V.: Queste categorie permeano probabilmente la mia ricerca, anche se non sono i concetti a indirizzarla a monte, ma è il lavoro che con essa prende forma a portarmi a una successiva riflessione sui contenuti. Nella costruzione di una serie di opere preferisco mantenere un approccio intuitivo il più a lungo possibile.

L’idea di luogo mi interessa nella sua accezione di porzione di spazio al contempo reale e immaginario; in questo senso può coincidere con l’idea di paesaggio come punto dove s’incontrano il mondo e lo sguardo.

Perlustrando luoghi e paesaggi – territori spesso concreti e fisici, a volte invece più astratti – metto in pratica una forma di cartografia, che considero soprattutto una raccolta di “rilievi”. Rilievi di un ambiente, di un’atmosfera dove magari lo spettatore entrerà a sua volta, attraverso il suo sentimento, le sue memorie.

G.L.: Il tuo lavoro può essere letto come un invito al viaggio?

L.V.: Diciamo che lavorando anzitutto sono io a viaggiare; non necessariamente in senso geografico, benché spesso accada, ma con esperienze e pensieri.

Che io ricordi, molto al di là della mia pratica artistica, fin da piccola sentivo il bisogno di esplorare punti di vista molteplici e relativi; mi premeva altrettanto (di)mostrare tale relatività al prossimo, soprattutto ai miei cari… Accenno a un punto nevralgico del mio esistere in quanto giovane essere umano, che forse ha trovato una sua direzione nel fare arte.

Se i miei lavori vengono accolti come inviti, nello specifico al viaggio, concreto come metaforico, ne sono onorata.

G.L.: Nella tua pratica operativa ti interessa la dimensione di cooperazione nella realizzazione del lavoro, in altre parole in questi viaggi hai compagnia?

L.V.: Il mio procedere è prevalentemente solitario. Tuttavia ho vissuto due episodi di lavoro partecipativo che si sono rivelati particolarmente intensi, sia nella condivisione di una metodologia artistica come forma d’indagine, sia nelle opere collettive che ne sono derivate.

Nel 2013 il workshop nella grotta di Pugnetto in Val di Lanzo, componente della mostra personale Inframondo al PAV di Torino; e le azioni di disegno di gruppo sulle rive del fiume Aterno a Pescara, nella cornice del mio progetto Hub Aterno: di pietre e di acque tra giugno e settembre dell’anno scorso.

Un nuovo episodio avrà luogo in giugno al Jardin Botanique di Bruxelles, un viaggio sul campo in un parco pubblico all’interno di un’area densamente urbanizzata, dove il cellulare sarà il mezzo fotografico per esplorare l’ambiente e generare una composizione collettiva, da cui emergerà un nuovo paesaggio… Che sono molto curiosa di scoprire!

Citando un significativo titolo di René Char, è senza dubbio coinvolgente “incontrarsi paesaggio” insieme ad altre persone.2

G.L.: È curioso perché non più tardi di pochi giorni fa, ma non ricordo dove esattamente, ho letto di questo testo di René Char Se rencontrer paysage avec Joseph Sima, mi sembra di ricordare che se ne parlasse in merito ad un’idea di trama, di tessitura, come se il paesaggio si modellasse plasticamente nell’incontro. È quello che stai pensando anche tu?

L.V.: Sento l’espressione se rencontrer paysage come “incontrare sé stessi nel paesaggio e in quanto paesaggio”, intendendo quest’ultimo come confluenza di esperienza concreta, interiorità, intelletto.

Penso a una dimensione in cui l’uomo non è spettatore, ma parte del paesaggio, che – come suggerisci – si può dire prenda forma nell’incontro dell’individuo con la materia del mondo.

Citando ancora Char, questo “essere tra”, che è anche un essere in e un essere con, descrive per me il presupposto da cui hanno origine i miei lavori; sia dove il legame con lo spazio fisico è evidente, sia quando il punto di partenza sensibile viene restituito con un’interfaccia più astratta.3

G.L.: “L’essere fra” implica molte cose fra cui anche la dimensione temporale che mi sembra nel tuo caso si inserisca nel paesaggio proiettando una vertigine geologica che si raccorda con la tua dimensione intima e privata puoi parlarne?

L.V.: Lo faccio raccontandoti di Diluvium, progetto in progress in cui convergono diversi aspetti di questo “essere tra”, che come dicevo esprime per me una premessa all’insieme del mio operare.

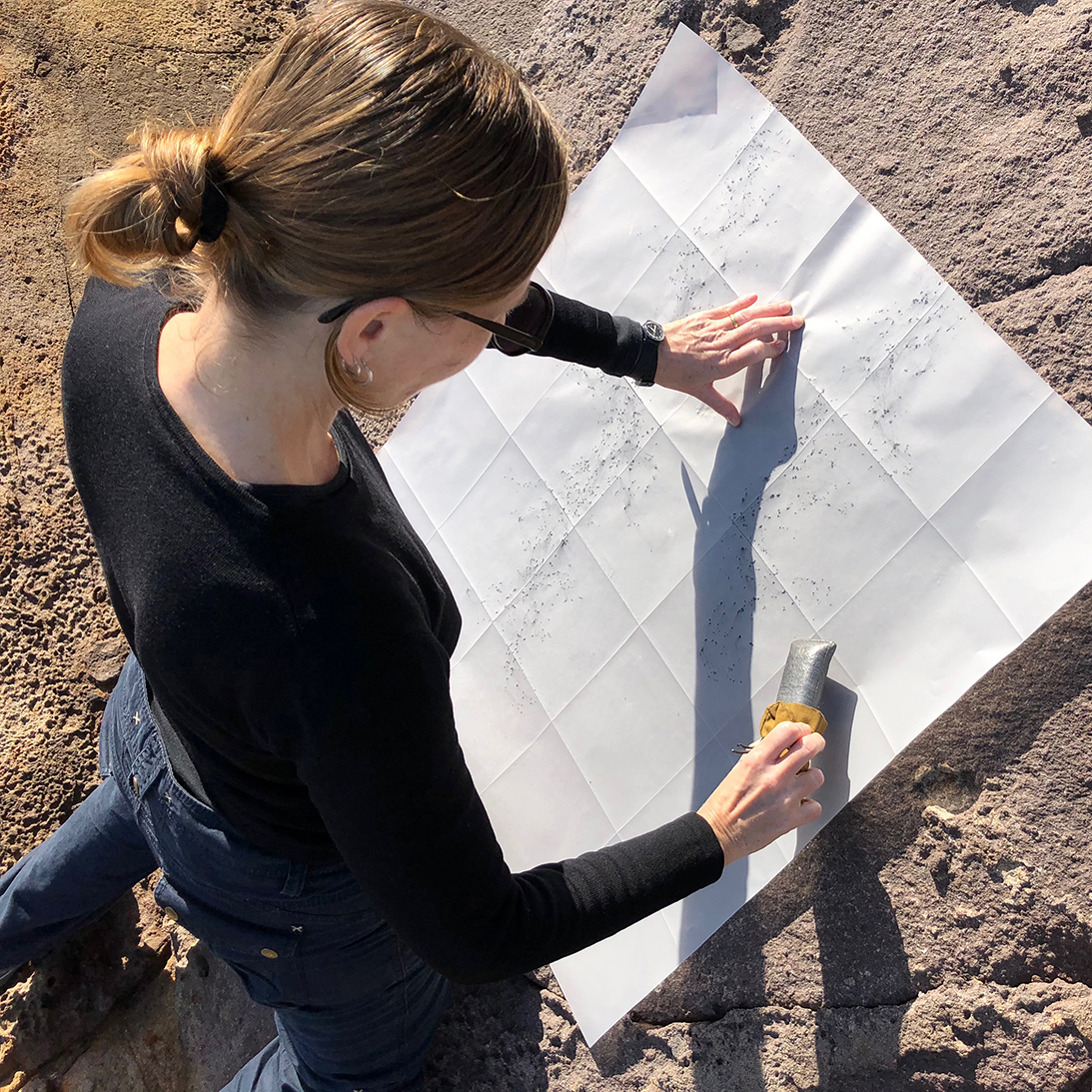

Si tratta di una nuova serie di frottages su carte semitrasparenti, realizzati principalmente su affascinanti pietre verdi che ho re-incontrato esplorando con Christoph i boschi del bacino del torrente Viana di Forno Canavese, e di alcune valli limitrofe.

Il disegno prende forma con il contatto fisico con le rocce. La carta è un’interfaccia tra le pietre e me, rileva la superficie minerale ma mostra anche qualcosa della sua struttura interna, così come della mia struttura interiore, delle mie emozioni. Come disse Piero Gilardi a proposito del mio progetto Inframondo, anche qui si può parlare di un processo di ibridazione con la natura, in cui convergono aspetti accidentali e soggettivi.

Personalmente, ho necessità di una relazione diretta e fisica con il pianeta, che mi conforta. Così come mi dà conforto la diversa misura temporale della “vita minerale”, il sentire che siamo davvero piccoli in un mondo molto più grande di noi, con una storia molto più lunga di quella della nostra specie umana (che peraltro è solo una tra milioni di altre), e che probabilmente continuerà ben oltre la nostra; e questo mondo che ci ospita – la Terra – è a sua volta un puntino in un mondo inimmaginabilmente più ampio e in fondo inafferrabile.

Tornando a Diluvium, la dimensione intima ha trovato un’ulteriore e inaspettata declinazione quando, cercando informazioni sulle rocce di cui sopra, ovvero sulla geologia delle Alpi Graie, ho incontrato molto spesso il nome di Martino Baretti. Ne avevo sentito parlare da bambina, non veramente per questioni geologiche, da mia prozia Olga, anziana sorella di mio nonno e fonte preziosa di racconti sulla mia famiglia materna. “Barba Baretti” – così era chiamato da mia prozia – era lo zio di mia bisnonna (“barba” significa “zio” in dialetto piemontese). Più tardi ho risentito parlare di lui da mia zia Anna, di cui ho recentemente trovato le scrupolose ricerche e gli scritti sul nostro antenato.

Valente alpinista, Barba Baretti esplorò numerose regioni delle Alpi occidentali, producendo una quarantina di pubblicazioni scientifiche. Morì nel 1905 nella casa dei miei bisnonni materni a Forno Canavese, curiosamente nella stanza che oggi uso come studio quando mi trovo lì.

Nella Geologia della provincia di Torino (1893), Baretti dedica alcune pagine al torrente Viana e al suo diluvium, termine ora desueto che indicava i depositi fluviali e glaciali del Pleistocene. Nota che nella parte alta del bacino del torrente abbondano i «ciottoli serpentinosi», popolarmente definiti “pietre verdi”. La serpentinite è tra le rocce metamorfiche oggi interpretate come resti di un braccio di oceano giurassico, quello Ligure-Piemontese, apertosi nella Pangea e poi scomparso per i movimenti di convergenza tra placca europea e placca africana, che hanno portato alla nascita delle Alpi.

Memorie della Terra, memorie di famiglia.

E anche memoria personale, Diluvium nasce infatti nei luoghi dove giocavo da bambina.

Note

1. AA.VV., Questo mondo è fantastico: vent’anni con Guido Carbone, Electa, Milano, 2008.

2. René Char, Se rencontrer paysage avec Joseph Sima, Editions Jean Hugues, Parigi, 1973.

3. «Je ne suis pas séparé. Je suis parmi.», ibidem.

Laura Viale (Torino, 1967) vive e lavora a Bruxelles. Si dedica alla ricerca artistica dalla fine degli anni 90.

I suoi progetti prendono forma attraverso diversi media, tra cui fotografia, disegno, installazione, video e tecniche digitali.

Artista residente presso la Djerassi Foundation in California, l’Atlantic Center for the Arts in Florida e la Fondation La Napoule in Francia, ha esposto in musei, gallerie e istituzioni, tra cui l’Istituto Italiano di Cultura e l’Académie royale des Beaux-Arts di Bruxelles; la Heinrich Gebert Kulturstiftung Appenzell; la Triennale di Milano; il PAV – Centro Sperimentale d‘Arte Contemporanea, la XIV Quadriennale di Roma – Anteprima Torino, il Museo di Scienze Naturali e il Festival Internazionale Cinemambiente di Torino; il Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce a Genova; il Museo Marino Marini di Firenze; la Galleria Civica d’Arte Contemporanea e il MART di Trento. Nel 2015 ha creato e curato “a due”. Arte Contemporanea in Italia e Belgio, un progetto triennale che ha aperto un dialogo tra artisti italiani e belgi presso l’Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Bruxelles. È co-fondatrice di MODO, associazione culturale con sede a Bruxelles, che si propone di stimolare la discussione sulla centralità e l’importanza dell’opera nell’odierno perpetuo panorama di immagini istantanee.

Interview with Laura Viale

#wordartist #interviewartist #lauraviale

Gabriele Landi: Hi Laura, for many artists, the golden age coincides with childhood. It is at this stage of life that a series of dynamics take off that later turn out to be fundamental to one’s artistic identity. Was it like that for you too? Tell us.

Laura Viale: Without an analytical approach, but with the help of a dream I had a few days ago, I try to recount places, circumstances, atmospheres that have certainly contributed to shaping my person and my artistic practice.

L.V.: I am with Christoph, my husband, in my parents’ house in Forno Canavese. The house is where it still is and with the appearance it had when we lived there, but it is also a galleon.

We are in the attic in my parents’ study, and we look out through the opening that overlooks the living room downstairs. On the walls hang the mats of Iraqi nomads and the paintings of some friends from Turin; in front is the wall-window that opens onto the garden and the valley below Monte Soglio.

We have to go to Turin to my mother’s and I prepare to go there with the houseboat.

So here I am at the stern of the house, in the small garden behind the other window-wall, to cast off the mooring lines.

I am at the same time in the castle of the sailing ship. We are setting off, I hold the helm and meanwhile, as the boat is also a brick house, the landscape slowly begins to flow behind the windows.

At this point I think it would be easier to go to Turin by car or bus and re-sail the houseboat where it was.

In order of appearance:

Forno Canavese, in the province of Turin, is the birthplace of my mother’s family. In the early 1970s, my parents, young architects, designed and then built a house there with a couple of friends, where I lived from third grade to eighth grade. But from a very young age I spent a lot of time in Forno with my grandmother and great-aunt. The country is not exactly a bucolic place. It experienced an industrial boom, with immigration from eastern and southern Italy, then a great depression. In this sense, and in miniature, a similar parabola to that of Turin.

But Forno is at the top of a valley at the foot of the Alps, surrounded by woods full of rocks and streams, and magnificent mountain huts that were already largely abandoned at the time. I played a lot in the forest, building emplacements between trees, stones and streams.

The mats of the Iraqi nomads are part of the objects and stories that accompanied my childhood.

I have never been there, but I am actually made in Iraq. Right after graduation, my parents worked for two years at the Italian archaeological mission in Baghdad. They were surveying ancient castles and fortresses in the desert, when the wind temporarily freed the ruins from the sand. Thanks to a miscalculation, I arrived earlier than they imagined and they decided to have me born in Italy.

Turin is and remains my city, where I was born and lived – except for a few parentheses – until ten years ago.

The Turin of my childhood was a place where various personalities of culture and art, later to become part of history, would meet in the piola (the Turin name for wine shop) or come to dinner at home. For example Carol Rama and her friend and gallery owner Giancarlo Salzano, or Aldo Mondino whose two-tone shoes and elegant pinstripes I loved. But also many others… We lived with Andrea Bruno, the architect who restored Rivoli Castle and with whom my parents often collaborated, and his family. With his children we remained brothers. Another integral part of my habitat in those years was the political militancy of my parents and many of their friends, sometimes shared with the city’s cultural circles, sometimes less so. In both of those worlds a lot of time was spent between us children, who enjoyed a lot of autonomy. And in fact other fraternities were born in those years, all of which are still fundamental parts of my family today.

But I also spent a lot of time alone, after school I often went to my parents’ studio, which shared space with a group of colleagues and a couple of illustrators. There were always lots of children’s books there and also other magazines of the time, from Linus to Alter Alter, to name but one that I had been reading since kindergarten! But above all, while waiting to go home, I would draw, draw and draw in the studio.

I won’t go into the symbolic interpretations of the galleon. But sterns, tops, moorings, in short the sea, allow me to force the narrative a little to get to a piece of my golden age that was not there in the dream.

My father loved the Mediterranean and Sicily in particular. In 1969, with a group of friends, who were also his study colleagues, he bought a house in Filicudi… For a million lire divided into six! I’ve been going to the island since then, I was just over a year old. We used to go there in the summer, at Christmas and Easter. Getting there was a real journey, and for me each time also a rite of initiation due to seasickness. But then I would have a blast, as they say in those parts. In total freedom, I explored rocks of a thousand colours and a thousand shapes; abandoned fields full of wheat that had only recently ceased to be tended, and vines that still yielded small bunches; ruins in which I sometimes even found dishes and pots and pans. Not to mention the fragments of pots and obsidian spikes that surfaced here and there after the rain.

The island has changed a bit since then… I still love the wild, rugged and strong nature of the island.

Returning to your question, my words tell of a habit since childhood to ‘frequent’ nature and artifice, of a direct and physical relationship with the planet but also of a contemplative approach to the world.

In fact, even when presented in a particularly abstract form, my work is essentially en plein air. Nature – in its most minimal urban expressions as well as in wild places – is always the starting point of my projects, in search of spaces of possible intersection between the external environment and the inner world. Whether drawing, photography, or other expressive avenues, it is a process aimed at detecting traces, rather than marking with one’s own imprint. And in fact, by playing with words, I more or less directly participated in a lot of surveying throughout my childhood.

G.L.: I read your answer and I felt in it, thank you Laura. Now I ask you to try to walk another piece of road. What studies did you do after secondary school? Were there any encounters that you consider important during this period?

L.V.: Trying to re-immerse myself for a moment in my feelings as an adolescent, I think that during that period I experienced (almost) everything and everyone as important encounters. And maybe even afterwards, at least for quite a while.

Anyway, for high school it’s back to the city. My parents propose linguistics in favour of a broad education, I don’t resist. In my spare time I work in architectural firms and above all at the Lastrego & Testa children’s book authors. At the age of eighteen, I start publishing my illustrations for some magazines.

This is the 1980s. My generation grows up amidst the legacy of the years of lead and the greyness of FIAT, of its shifts that determine the atmosphere of the entire city, and of its allied industries, which at the time included almost everything. The political militancy that involved the boys of previous decades no longer corresponds to us. Perhaps this is the origin of the intense underground climate of Turin at that time, from music to all the arts. At high school, I met Elisa Sighicelli and with her Francesco Bernardelli. We are always together at evenings and concerts, but we are also interested in contemporary art, which for me still remains a familiar and shared acquaintance.

These are also years of important encounters with other worlds. In summer I am ‘with family’ in France, England and California to practise the languages I study at school. And with my parents we travel to India, China and Tibet, then to Yemen. Later I will continue to travel, alone and with friends.

Writing to you, I realise that, curiously enough, the artist residencies I did so many years later were almost in the same places as those stays to study foreign languages.

After two years of Literature and Philosophy, which I always enrol in because of the broad spectrum, I finished the courses and exams that interested me most and realised that it was time to study what I really wanted to do. Which at that time was illustrating books and magazines. So in the late 80s and early 90s I attended the IED in Milan. The experience I had already gained in that field allowed me from the very first year to also start working as an author, and then to undertake the all-round activity of illustrator and graphic designer for various publishing houses. And especially for Marcello Baraghini’s Stampa Alternativa, with the Millelire book series.

In those years, I also began to approach as an artist the ‘fine arts’ – which I had always looked at as an observer before – with sporadic episodes and with the tools that were closest to my heart, those of my illustrations.

A personal and total event, the sudden death of my father, upset me and at the same time made a change or rather a broadening of perspective urgent. Which from an artistic point of view translates into an initial approach to landscape, adopting a camera as a tool for a veiledly ironic investigation into the search for empathy with nature.

Ettore Sottsass, whom I met to prepare a series of his Millelire and with whom I got to know a lot in that period, lent me one of his Hasselblads for these first explorations.

The result was a series of works that were noticed by an art-loving friend and young collector, Massimo Sterpi. Thanks to him and Elisa, shortly afterwards I met Guido Carbone, who decided to exhibit one of my works in the studio of his gallery. From that moment on, while continuing to work with graphics and illustration, I entered full-time into artistic practice and after about a year I made my debut at Guido’s with the solo exhibition If You Lived Here You’d Be Home by Now.

Another important personal event cannot be overlooked in this story. After this first exhibition, along with the professional understanding with Guido came the sentimental bond that would unite us for eight years.

G.L.: What years are we talking about and what was the climate in Turin?

L.V.: We are at the end of the 1990s. Especially in the second part of that decade, Turin was challenging the FIAT crisis by seeking and investing in new or rediscovered vocations, among which art and culture excelled. The city that takes shape is different from that of my adolescence. This is evidenced, among other things, by a renovated and gentrified old town centre in its popular parts that were still well established at the end of the 1980s, and by the countless dehors and bars scattered all over the place and packed with people: an absolute novelty for the Turinese, unimaginable a few years earlier.

In this atmosphere, many small and large, public and private initiatives took shape, many of them linked to young creativity. In addition, Artissima, perhaps the first Italian fair to promote the participation of foreign and especially young galleries, was born and grew. A few years later came Luci d’Artista. The public administration also creates programmes to support young art, limited episodes compared to what happens in other countries, but nevertheless concrete and new facts. This process definitely refreshes the cultural climate of Turin, which presents itself in 2000 as the Italian city of contemporary art.

Personally, I breathe good and stimulating air among old acquaintances and new encounters. Of course, to put it bluntly, artist residencies abroad and working beyond the city borders, with Giancarla Zanutti in Milan and Andrew Mummery in London, also benefit my lungs.

But back to Turin.

In answering your first question, I mentioned some artists from other generations. I want to talk about my own by starting with the most sister of my siblings. Maria Bruno, aka Sister Flash, has been a street artist and raver since the early 90s. She occasionally skirts the ‘art world’. But her fluid spirit tells a lot about the many valuable interactions between different human and cultural contexts in the Turin of the turn of the millennium; which for Maria will continue well beyond, until 2016, when she flies into the sky just in the time of a flash.

Then there are the artists working with Guido Carbone at that time, with whom we are family. Important ties were born for me, among others with Mario Consiglio, Francesco Lauretta, Maurizio Vetrugno, Monica Carocci. And beyond the gallery, with the artists Maria Bruni (almost the same name as Maria Bruno), Maura Banfo, Giulia Caira; Luisa Perlo, Giorgina Bertolino, Francesca Comisso and Lisa Parola of the curatorial collective a.titolo; the collectors Memo Basso and Ernesto Alessio; Guido Costa, Luca Beatrice, Alberto Peola, Alvise Chevallard of Arte Giovane… An incomplete list of friendships that, where possible, remain.

In a brief stream of memories inevitably in philological defect, and limiting myself to artists, in my Turin of the art of that time there are also Pierluigi Pusole (who also worked with Guido for a long time), Daniele Galliano, Enrica Borghi, Botto and Bruno, Bartolomeo Migliore, Marzia Migliora, Saverio Todaro, Nicus Lucà, Paolo Piscitelli, Paolo Leonardo, Paolo Grassino… To mention only a few of the people in the flesh who nurtured a bubbling and fermenting humus, with whom only a few names remain associated over the years and for those who were not there at the time.

At this point, I would like to talk about Guido, although for me it remains a delicate matter… I rely on the words of Luca Beatrice in the book in his memory, when he speaks of the years above: ‘In these years Guido himself underwent a significant transformation: from gallery owner he tended to turn into “producer”. With the artist who intrigued him, provided there was intellectual esteem and complicity, Carbone established a very close dialogue that often led to changing the cards on the table, if not radically altering plans. “1

In fact he had this approach with everyone and everything, I would even say with himself. I think it is mainly for this reason that with the artists he worked with, but also with collectors and curators, real friendships were often created, with all that this could entail.

Together we travelled almost symbiotically through the years I am recounting. Then suddenly Guido fell ill, we realised that time was short. Perhaps it is precisely for this reason that he, although increasingly tired, does not stop working. It is clear to me that the most important thing for me is to share this time with him, and we do it as we have always done, intersecting feelings, work, projects, curiosity – and also illness. These are three very intense years. He left this world in 2006, not even two days after opening Bob & Roberta Smith’s The Humanist in the gallery.

Now, it would seem that this story of mine is marked by encounters with death. Also, yes, but I am not an exceptional case. At certain points it happens. Very important pieces of you leave forever, decreeing absolute ‘before’ and ‘after’. And even generating, in some ways, several lives within a single existence…

G.L.: In those years, what work did you do?

L.V.: In those years I worked a lot with photography, at dusk or during the night. I explore seemingly remote natural environments, but often around the corner from home, through the broad light spectrum of the contemporary landscape, where the colours of artificial light mix with the colours ‘made’ of matter.

With long exposures, coloured lights found in or added to the places where I find myself give rise to series featuring the same details photographed in different colours, then ‘catalogued’ in titles with pantone colour numbers. Working in analogue and en plein air, I produce images that are “virtual” no more than I can define them as “different perceptions of the real”.

I consider photography a contemplative practice. Just as long exposures allow the lens to detect what we sometimes see with our eyes, but often do not retain, photographing allows the gaze a few seconds longer than the time we usually allow it. The result is an image that in turn can invite contemplation.

G.L.: Why did you choose to work with photography?

L.V.: There have always been cameras in the house, access was free and, I think on my tenth birthday, I received a small automatic as a gift. From a very young age I have taken photographs, for home explorations, on trips, then sometimes for graphic design work.

When I approached ‘fine arts’ I was fascinated by, among others, artists who in the 1980s had started to use the medium of photography in a non-documentary way, from the Dusseldorf school to Jeff Wall or Richard Prince, to name a few.

I started working with photography mainly out of an almost physiological need to ‘look outside’, to (re)encounter the world. That is, to look for a new meeting point between myself and the world.

Amidst watercolours, acrylics, linocuts and whatever else gave shape to book covers and illustrations, moreover with satisfaction, the photographic lens offered itself as the window through which to frame portions of ‘reality’ where my eye could wander.

In retrospect, the encounter with colours ‘made’ of light and a decidedly empirical use of the medium opened up components of my creative approach that can be found in all my subsequent works, whichever expressive path I use. For example, the mixture of the “objective” and the subjective; the accidental factor; the idea of the work as a threshold, a meeting point between inside and outside but also a place without narrative references, open to the perception and imagination of the observer.

G.L.: In this meeting point between you and the world, are the idea of place/landscape/cartography categories that you investigate?

L.V.: These categories probably permeate my research, although it is not the concepts that direct it upstream, but it is the work that takes shape with it that leads me to a subsequent reflection on the content. When constructing a series of works I prefer to maintain an intuitive approach for as long as possible.

The idea of place interests me in its meaning of a portion of space that is both real and imaginary; in this sense it can coincide with the idea of landscape as a point where the world and the gaze meet.

By patrolling places and landscapes – often concrete and physical territories, sometimes more abstract – I put into practice a form of cartography, which I consider above all a collection of ‘reliefs’. Reliefs of an environment, of an atmosphere where perhaps the viewer will enter in turn, through his feelings, his memories.

G.L.: Can your work be read as an invitation to travel?

L.V.: Let’s say that by working I am first of all travelling; not necessarily in a geographical sense, although it often happens, but with experiences and thoughts.

As far as I remember, far beyond my artistic practice, ever since I was a child I felt the need to explore multiple and relative points of view; I was equally keen on (di)showing this relativity to others, especially to my loved ones… I mention a nerve point of my existence as a young human being, which has perhaps found its direction in making art.

If my works are received as invitations, specifically to travel, concrete as well as metaphorical, I am honoured.

G.L.: In your practice you are interested in the dimension of cooperation in the realisation of the work, in other words in these journeys you have company?

L.V.: My proceeding is predominantly solitary. However, I have experienced two episodes of participatory work that proved to be particularly intense, both in the sharing of an artistic methodology as a form of investigation and in the collective works that resulted.

In 2013, the workshop in the Pugnetto cave in Val di Lanzo, which was part of the Inframondo solo exhibition at PAV in Turin; and the group drawing actions on the banks of the Aterno river in Pescara, in the framework of my project Hub Aterno: di pietre e di acque (Hub Aterno: of stones and waters) between June and September last year.

A new episode will take place in June at the Jardin Botanique in Brussels, a field trip in a public park within a densely urbanised area, where the mobile phone will be the photographic medium to explore the environment and generate a collective composition, from which a new landscape will emerge… Which I am very curious to discover!

Quoting a meaningful title by René Char, it is undoubtedly engaging to ‘meet landscape’ together with other people.2

G.L.: It is curious because no more than a few days ago, but I don’t remember where exactly, I read about this text by René Char Se rencontrer paysage avec Joseph Sima, I seem to remember that he was talking about an idea of weave, of texture, as if the landscape was modelled plastically in the encounter. Is that what you are thinking too?

L.V.: I hear the expression se rencontrer paysage as ‘meeting oneself in the landscape and as landscape’, understanding the latter as a confluence of concrete experience, interiority, intellect.

I am thinking of a dimension in which man is not a spectator, but part of the landscape, which – as you suggest – can be said to take shape in the encounter of the individual with the matter of the world.

Quoting Char again, this “being between”, which is also a being in and a being with, describes for me the assumption from which my works originate; both where the link with physical space is evident, and when the sensitive starting point is returned with a more abstract interface.3

G.L.: “Being between” implies many things, including the temporal dimension, which in your case seems to me to be inserted into the landscape by projecting a geological vertigo that connects with your intimate and private dimension, can you talk about it?

L.V.: I will do so by telling you about Diluvium, a project in progress in which various aspects of this “being between” converge, which, as I said, expresses for me a premise for my work as a whole.

It is a new series of frottages on semi-transparent paper, mainly made on fascinating green stones that I re-encountered while exploring with Christoph the woods of the Viana torrent basin in Forno Canavese, and some neighbouring valleys.

The drawing takes shape through physical contact with the rocks. The paper is an interface between the stones and me, it detects the mineral surface but also shows something of its internal structure, as well as my inner structure, my emotions. As Piero Gilardi said about my Inframondo project, here too we can speak of a process of hybridisation with nature, in which accidental and subjective aspects converge.

Personally, I need a direct and physical relationship with the planet, which comforts me. Just as the different temporal measure of ‘mineral life’ comforts me, the feeling that we are indeed small in a world much larger than ourselves, with a history much longer than that of our human species (which, moreover, is only one among millions of others), and which is likely to continue well beyond our own; and this world that hosts us – the Earth – is itself a dot in an unimaginably larger and ultimately elusive world.

Returning to Diluvium, the intimate dimension found a further and unexpected declination when, searching for information on the rocks mentioned above, i.e. on the geology of the Graian Alps, I came across the name of Martino Baretti very often. I had heard of him as a child, not really on geological matters, from my great-aunt Olga, my grandfather’s elderly sister and a valuable source of stories about my maternal family. ‘Barba Baretti’ – as he was called by my great-aunt – was my great-grandmother’s uncle (‘barba’ means ‘uncle’ in Piedmontese dialect). I later heard about him again from my aunt Anna, whose painstaking research and writings on our ancestor I recently found.

A talented mountaineer, Barba Baretti explored numerous regions of the Western Alps, producing some forty scientific publications. He died in 1905 in my maternal great-grandparents’ house in Forno Canavese, curiously enough in the room that I now use as a study when I am there.

In the Geology of the Province of Turin (1893), Baretti dedicates a few pages to the Viana torrent and its diluvium, a term now obsolete that indicated fluvial and glacial deposits of the Pleistocene. He notes that ‘serpentine pebbles’, popularly referred to as ‘green stones’, abound in the upper part of the stream basin. Serpentinite is among the metamorphic rocks interpreted today as the remains of a Jurassic ocean arm, the Ligurian-Piedmontese Ocean, which opened up in Pangaea and then disappeared due to convergence movements between the European plate and the African plate, which led to the birth of the Alps.

Earth memories, family memories.

And also personal memories, Diluvium was in fact born in the places where I played as a child.

Notes

1. AA.VV., Questo mondo è fantastico: vent’anni con Guido Carbone, Electa, Milan, 2008.

2. René Char, Se rencontrer paysage avec Joseph Sima, Editions Jean Hugues, Paris, 1973.

3. “Je ne suis pas séparé. Je suis parmi.”, ibid.

Laura Viale (Turin, 1967) is based in Brussels. She has been dedicated to artistic reseach since the late 1990s.

Her projects take shape through a wide range of media including photography, drawing, installation, video and digital techniques.

An artist-in-residence at the Djerassi Foundation in California, the Atlantic Center for the Arts in Florida, and the Fondation La Napoule in France, she has shown her work in museums, art galleries, and institutions, including the Italian Cultural Institute and the Académie royale des Beaux-Arts in

Brussels; the Heinrich Gebert Kulturstiftung Appenzell; Triennale in Milan; PAV – Centro Sperimentale d‘Arte Contemporanea, 14th Rome Quadriennale – Anteprima Torino, Museum of Natural Science, and Festival Internazionale Cinemambiente in Turin; Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce in

Genoa; Museo Marino Marini in Florence; Galleria Civica d’Arte Contemporanea and MART in Trento. In 2015 she created and curated “a due”. Arte Contemporanea in Italia e Belgio, a three-year project opening a dialogue between Italian and Belgian artists at the Italian Cultural Institute of Brussels. She is co-founder of MODO, a cultural association based in Brussels, aimed at stimulating the dialogue on the centrality and importance of artwork in today’s perpetual panorama of instant images.

Loto #1 – 185, Loto #1 – 334, 1999

C-print sotto plexiglas, ognuna 60 x 60 cm, ed. 3

Laura Viale

Lotus #1 – 185, Lotus #1 – 334, 1999

C-prints under plexiglas, 60 x 60 cm each, ed. 3

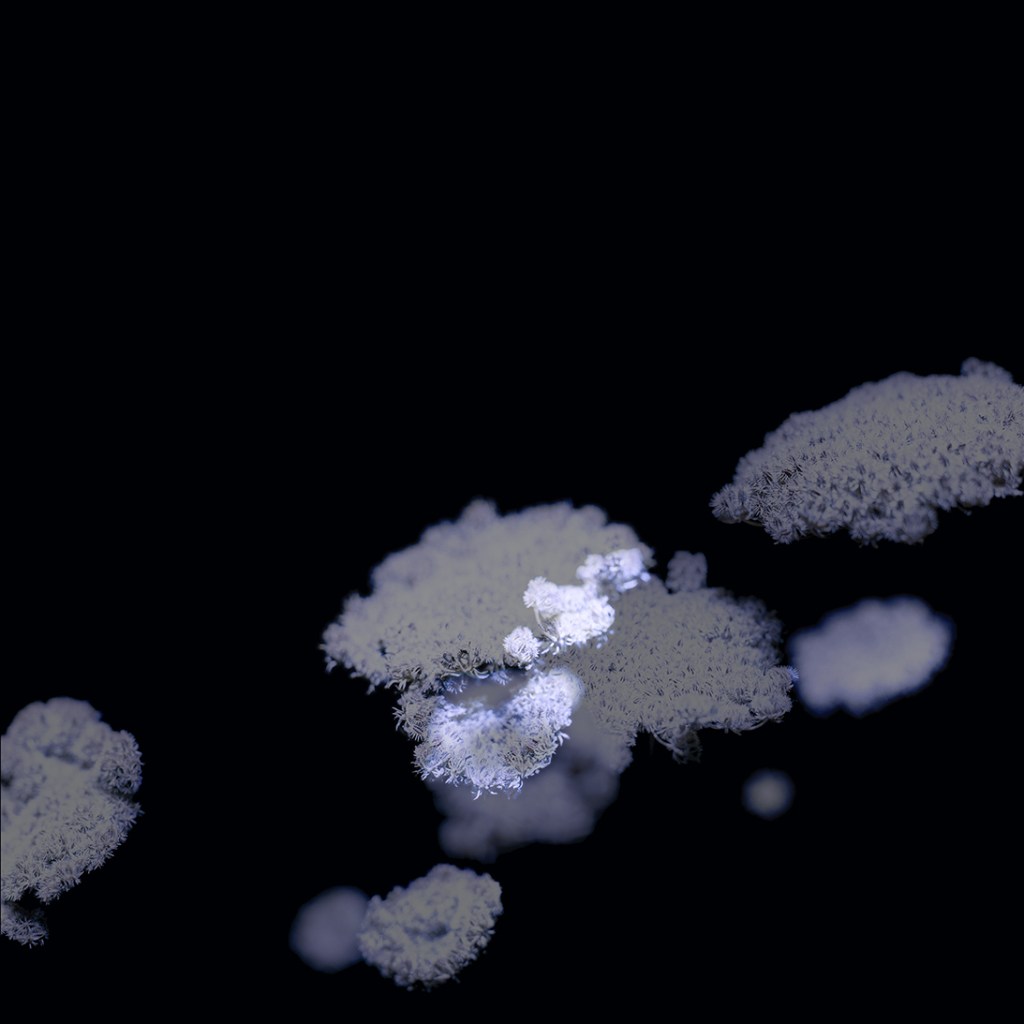

Di là fioriscono carote selvagge, #4, 2018-2019

Stampa Fine Art Giclée su Hahnemuhle PhotoRag 308 100% cotone, 100 x 100 cm, ed. 3

Laura Viale

Di là fioriscono carote selvagge [Wild carrots bloom over there], #6, 2018-2019

Fine Art Giclée print on Hahnemuhle PhotoRag 308 100% cotton, 100 x 100 cm, ed. 3

Di là fioriscono carote selvagge, #6, 2018-2019

Stampa Fine Art Giclée su Hahnemuhle PhotoRag 308 100% cotone, 100 x 100 cm, ed. 3

Laura Viale

Di là fioriscono carote selvagge [Wild carrots bloom over there], #6, 2018-2019

Fine Art Giclée print on Hahnemuhle PhotoRag 308 100% cotton, 100 x 100 cm, ed. 3

Inframondo, Emma Kunz Grotte, #22, #23, #24, 2019

Grafite su carta millimetrata, ognuno 75 x 80 cm / 80 x 75 cm

Laura Viale

Inframondo [Underworld], Emma Kunz Grotte, #22, #23, #24, 2019

Graphite on graph paper, 75 x 80 cm / 80 x 75 cm each

Diluvium (Linea Insubrica), #1, #2, 2023

Particolari, grafite su carta da lucido, 580 x 110 cm e 495 x 110 cm

Laura Viale

Diluvium (Insubric Line), #1, #2, 2023

Details, graphite on tracing paper, 580 x 110 cm and 495 x 110 cm

Diluvium, #27, 2022

Grafite su carta cerata, 25 x 40 cm

Laura Viale

Diluvium, #27, 2022

Graphite on waxed paper, 25 x 40 cm