#paroladartista #intervistagallerista #caterinagualco

Gabriele Landi: Ciao Caterina, a quando risalgono i tuoi primi incontri con l’arte?

Caterina Gualco: Alla notte dei tempi… Sono cresciuta in un giardino incantato, con un frutteto, piante di rose e di iris… ricordo una mattina di primavera… i meli e i peri come nuvole bianche e le aiuole tappezzate da migliaia di fiorellini azzurri. Ecco, credo proprio che quello sia stato il primo momento in cui ho pensato alla bellezza come a una fata madrina.

Un po’ più avanti – ero in quinta elementare o in prima media – a scuola mi avevano regalato come premio un mini libro su Amedeo Modigliani… Me ne sono innamorata immediatamente e guardando le sue figure allungate mi sono trovata a confrontarle con quelle di Simone Martini, che conoscevo già. Penso che quello sia stato il primo movimento che mi ha spinto a trasformare l’oggetto del mio interesse in oggetto del mio lavoro.

GL: Che studi hai fatto e quali sono stati, se ci sono stati, gli incontri importanti che hai fatto durante gli anni della tua formazione.

CG: Sono uscita dalla scuola elementare con il massimo dei voti e avrei tanto voluto frequentare il liceo classico. Ma la scelta fu decisa da mio padre… una scuola solo femminile e vicina a casa… E mi toccò il Liceo Linguistico Grazia Deledda di Genova, cosa che mi rese infelice per parecchio tempo. Poi però mi appassionai alle lingue moderne (si studiava inglese, francese, spagnolo oltre che latino) e in quella stessa scuola ebbi la fortuna di incontrare la persona che “mi aprì il terzo occhio”, come mi piace raccontare. Era proprio una straordinaria insegnante di storia dell’arte, Maria Grazia Carbone Pighetti, che con le sue lezioni appassionate, condite da ironia e da un pizzico di malizia, mi aiutò a individuare quello che sarebbe poi stato il massimo interesse di tutta la mia vita nel campo dello studio e del lavoro.

Devo in ogni caso moltissimo a mia madre, donna molto colta ed estremamente sensibile, maestra per vocazione, che già nei primi anni mi aveva portato per mano nel territorio divino dell’arte.

G.L.: Fra le varie possibilità che il mondo dell’arte offre come sei arrivata all’idea di aprire una galleria?

C.G.: Non ho frequentato l’Università perché la mia famiglia di origine aveva bisogno del mio contributo. Ho lavorato 4 anni con le lingue, poi mi sono sposata, molto giovane. Qualche tempo dopo mia madre si è ammalata gravemente ed è morta… E io a mia volta sono stata ammalata un anno, tutto psicosomatico…

Due anni dopo il mio giovane marito è andato in Inghilterra per lavoro. Mi ha proposto di andare con lui, era il maggio del 1968, durante la pausa tra i due periodi caldi… Sono stata 15 giorni sola a Londra… ho visto tutto quello che era possibile vedere. Ho camminato migliaia di chilometri

In questa città che mi sembrava cento anni avanti le nostre… i figli dei fiori, le minigonne, le mostre…

Proprio durante il viaggio di ritorno ho deciso che non potevo restare a casa a fare la brava madre di famiglia, la signora della piccola borghesia. Volevo lavorare e volevo lavorare nel mondo dell’arte. Non potevo insegnare, non avevo i titoli necessari… e alla fine ho deciso che l’unica possibilità era aprire una galleria.

Pensavo che sarebbe stato facile… e non lo è stato affatto!

GL.: Racconta?

C.G.: Racconto… un racconto lungo mezzo secolo…

Partiamo dalla scelta, meglio, dall’invenzione del nome, Unimedia, trovato quando i vari “mixta media” “multi media” ecc. non erano ancora all’orizzonte. Un nome paradossale che mette assieme un singolare e un plurale, nel tentativo di sintesi di “arte come primo e più importante mezzo di comunicazione di massa”.

Poi, ovviamente, la ricerca dello spazio, nel centro storico, anche lì quando il centro storico era abbastanza evitato per motivi di sicurezza. Ma quello che a me interessava era occuparmi di contemporaneo proprio nel cuore della città vecchia. Avevo trovato lo spazio, molto affascinante, grande e… freddissimo d’inverno, a Palazzo Barabino, un palazzo del ‘600, non nobile, ma in ogni caso con volte altissime e persino un’alcova, nella quale avevo collocato il mio ufficio suscitando commenti birichini da parte dei frequentatori uomini… Allora ero giovane, i tempi erano molto diversi e molto spesso dovevo difendermi!

Si accedeva allo spazio, composto appunto da un salone che era un cubo perfetto, 6 metri per 6 con la volta anch’essa a 6 metri dal pavimento, salendo una ripida e stretta scala di ardesia… motivo di altri commenti non sempre gradevoli. C’era poi l’alcova, un magazzino e i servizi. Un piccolo, delizioso terrazzo si affacciava su vico dei Garibald, una traversa di Via Luccoli, l’antico Lucus romano.

La prima avventura negativa era arrivata durante i lavori necessari per rendere lo spazio adatto allo scopo. Qualcuno di cui mi fidavo mi aveva proposto una piccola impresa… dopo due giorni dall’inizio dei lavori avevo scoperto che era una banda di disperati, senza capacità e senza… assicurazione… Una specie di trabattello che avevano costruito per imbiancare il soffitto aveva ceduto e uno di quei poveretti si era rotto una gamba… Grane a non finire, che avrebbero potuto smorzare qualsiasi entusiasmo che non fosse stato di acciaio inossidabile!

G.L.: Una volta aperto lo spazio come hai orientato la programmazione dell’attività?

C.G.: Per rispondere a questa domanda devo parlare della situazione dell’arte contemporanea a Genova all’inizio degli anni 70. Non esisteva un museo, non uno spazio pubblico dove promuovere incontri, l’arte contemporanea era davvero gestita da pochi privati che avevano un buon pubblico, molto limitato, di collezionisti attenti. Le gallerie che contavano in città erano veramente poche, ma molto potenti. C’era la storica Galleria Rotta, una aperta nel 1917 da Roberto Rotta, che aveva avuto un contratto con De Pisis, De Chirico e presentava gli artisti già affermati delle avanguardie storiche. C’era la Galleria La Polena, che era decisamente coinvolta con l’astratto geometrico, sia storico, sia contemporaneo. E c’era la Bertesca, il cui direttore Francesco Masnata aveva scelto la strada del Concettuale e dell’Arte Povera… Tutti questi così detti movimenti o gruppi erano assolutamente inavvicinabili, pena … la morte.

Io, totalmente sprovveduta ma non al punto di non saperlo, avevo cominciato a muovermi con piccoli passi di bimbo… presentando artisti ai quali arrivavo talvolta anche in modo stravagante. L’artista con cui avevo aperto la galleria era il veneziano Saverio Rampin, un allievo di Vedova, che mi era stato segnalato da quello che sarebbe poi diventato anche un grande amico, il Signor Scheggi della Tipografia Artigiani Grafici.

Nel deserto genovese c’era un critico illuminato che scriveva recensioni sul giornale Il Lavoro, Germano Beringheli. Anche lui mi aveva dato indicazioni su giovani artisti praticamente sconosciuti ma molto interessanti! Per fare un esempio cito Beppe Dellepiane… La sua mostra, in cui esponevamo una bicicletta coperta di bronzina, montata su una pedana con i cordoni rossi attorno, aveva dato vita a uno scandalo nell’ambiente. Il giornale Il Secolo XIX aveva pubblicato una recensione di Sergio Paglieri che si chiedeva se la “giovane gallerista di Vico dei Garibaldi” (indirizzo della galleria) non stesse prendendo in giro tutti.

G.L.: Stavi davvero prendendo in giro tutti? Dopo questi primi episodi come prosegue l’attività?

C.G.: In realtà mi muovevo in un mare di difficoltà… Dopo un anno di galleria il mio allora giovane marito, che all’inizio sembrava entusiasta del mio lavoro, mi aveva posto l’aut aut: la galleria o me… Soldi pochi, pochissimi, due bambine piccole… Mio padre contrario… ragionevolmente avrei dovuto piantare tutto! Ma chi nasce con una passione riceve sì un grande dono dalla fata madrina… ma poi non c’è niente da fare…non si può mollare

Cercavo di conoscere il più possibile cosa stesse succedendo nel mondo dell’arte con tutti i mezzi a disposizione a quei tempi, ed erano veramente pochi. Ancora attraverso Germano Beringheli avevo scoperto il Gruppo Transazionale sardo, che vagava tra il concettuale e il ricupero di una certa figurazione. Uno dei suoi membri, Ermanno Leinardi, aveva veramente catturato la mia attenzione… I suoi quadri, su tela montata su telaio nel modo più tradizionale, presentavano delle “O” in movimento, nere su campo bianco o bianche su campo nero. Era una mostra bellissima, presentata da Beringheli e Corrado Maltese, allora appena arrivato a Genova come titolare della cattedra di Storia dell’Arte all’Università. Questa mostra aveva scatenato le ire dei soliti benpensanti con conseguenti attacchi sui giornali. Il più feroce era il Secolo XIX, conservatore come la maggior parte dei genovesi.

Nella primavera del 1972 ero riuscita faticosamente a ottenere di partecipare alla Fiera d’Arte di Genova. Avevo uno stand secondo me bellissimo… con – tra gli altri – un lavoro di Beppe Dellepiane, abbastanza tragico e poco adatto a una Fiera. Era una specie di sarcofago con un motore spento dentro. Il Direttore della Fiera aveva avuto la buona idea di organizzare una caccia al tesoro e una delle tappe era nel mio stand, proprio nell’opera di Dellepiane. Lascio immaginare il caos che ne era nato!

Nel 1972 ho presentato una mostra di Bice Lazzari, la grande astrattista italiana degli anni trenta. La mostra era straordinaria, molto bene accolta dal pubblico e dalla critica. Tra le altre cose, a me aveva anche dato l’opportunità di conoscere il grande Carlo Scarpa, che allora lavorava alla ristrutturazione del Teatro Carlo Felice ed era il cognato di Bice. Il mattino dell’inaugurazione era venuto a vedere la mostra. Ricordo tutto questo con una grande emozione… io ho sempre amato moltissimo il lavoro di Scarpa, ho visto tutto quanto ha costruito e ristrutturato…sono andata ben due volte ad Altivole di Asolo per vedere il suo Monumento Brion…

Poco alla volta intanto io prendevo sicurezza e allargavo il mio orizzonte. Nel 1972 c’è stata una mostra di artisti cecoslovacchi, tra i quali il già notissimo Jiri Kolar e Kolibal, che lo sarebbe diventato di lì a poco. E nel 1973 ho organizzato la rassegna “Verso il bianco”, curata da Paolo Fossati (il cui libro “L’immagine sospesa” aveva fatto scoprire al mondo l’astrattismo italiano). Era una mostra con moltissimi artisti, alcuni giovani e ancora sconosciuti e altri già molto affermati; per nominarne alcuni, Bonalumi, Calderara, Gastini, Griffa, Manzoni, Fontana.

E poi, finalmente, la prima mostra davvero storica “Astrattisti a Como negli anni trenta”. Per realizzarla e trovare le opere ero andata a Como e con l’aiuto di Luciano Caramel, grande persona e grande amico, avevo incontrato Radice e Galli, ancora viventi. Due piccoli aneddoti: Radice era convinto che io fossi là per rubargli le opere e Galli mi faceva la corte inneggiando al duce!

G.L.: Come andò la mostra sugli astrattisti degli anni 30 e quali altri artisti oltre a Radice e Galli erano inclusi da Caramel nella rassegna?

C.G.: “Astrattisti a Como negli anni trenta” Carla Badiali, Aldo Galli, Carla Prina, Mario Radice, Manlio Rho, Arch. Giuseppe Terragni. Catalogo con testo di Luciano Caramel. Dal 24 gennaio 1974

Questo è l’annuncio con cui avevamo comunicato l’evento. Era stato fatto anche un catalogo, con testo di Luciano Caramel. La mostra era molto bella ed era stata accolta molto bene! Mi ricordo che avevo venduto un bel disegno di Terragni relativo alla Casa del Fascio di Como. A questo proposito ho due piccoli aneddoti, molto significativi dell’epoca e dell’atmosfera genovese. Dopo alcuni giorni dall’inaugurazione era arrivato in galleria un signore dall’aspetto abbastanza dimesso e insignificante, tutto grigio negli abiti, nei capelli e nella faccia. Si era soffermato a lungo a guardare le opere e prima di andarsene mi aveva dato il suo biglietto da visita, dicendomi che voleva comprare il disegno di Terragni, di chiamarlo quindi finita la mostra. Io ero convinta che la cosa sarebbe finita lì… Poco dopo era venuto in galleria un collezionista, veramente famoso e importante al quale una delle gallerie di punta doveva la sua fortuna. Gli avevo raccontato della visita esprimendo con lui le mie perplessità… Lui mi aveva detto di tutto… come potevo non sapere che il signore in grigio era uno dei più grandi collezionisti della sua epoca? Bene, non lo sapevo…

Finita la mostra, avevo telefonato ed ero andata a consegnare il disegno. E un’altra storia incredibile mi aveva accolto… In quella bellissima casa, con opere straordinarie alle pareti, c’era una stanza segreta, nella quale venivano appesi i lavori acquistati da gallerie che non erano quella di riferimento. Confesso che qui mi piacerebbe fare tutti i nomi, ma il senso di discrezione non me lo permette, anche se tutti i protagonisti non sono più con noi.

1) “Il corpo come linguaggio” prima presentazione del libro di Lea Vergine a cura di Germano Beringhelii, Vittorio Fagone, Paolo Fossati, Edoardo Sanguineti, Lea Vergine

2) Psichico e formale a cura di Vittorio Fagone

3) Struttura e misura a cura di Germano Beringheli

4) AA. VV. “Il gesto coatto”

5) La visione fluttuante” a cura di Edoardo Sanguineti e Martino Oberto OM

6) Tavola rotonda conclusiva sugli argomenti trattati, moderatore Corrado maltese

E’ stato presentato un grande numero di artisti, molte volte difficili da trovare, e questa è stata per me una palestra incredibile, una miniera di contatti, e anche la consapevolezza che, volendo, si può arrivare ovunque, senza praticamente limiti.

Faccio qualche esempio:

Per “Il corpo come linguaggio” Vito Acconci, Gunter Brus, Gilbert & George, Urs Luthi, Hermann Nitsch, Luigi Ontani, Gina Pane, Michele Zaza.

Per “Psichico e Formale” Max Bill, Victor Vasarely, Richard Paul Lohse, Antonio Calderara, Bice Lazzari, Giorgio Griffa, Claudio Verna.

Per “Struttura e misura” Marco Gastini, Stanislav Kolibal, Maur Reggiani, Riccardo Guarneri, Piero Manzoni, Mario Nigro, Sol LeWitt.

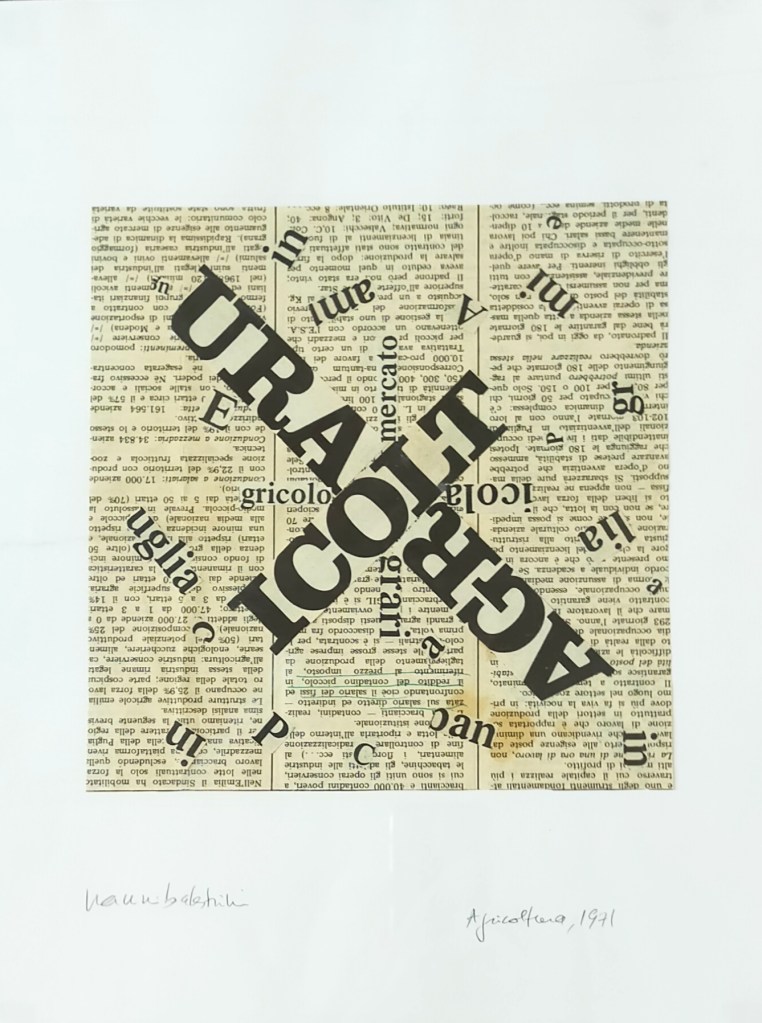

Per “Il gesto coatto” Lucio Fontana, Albino Galvano, Osvaldo Licini, Emilio Scanavino.

Per “La visione Fluttuante” Carlo Belloli, Arrigo Lora-Totino, Mirella Bentivoglio, Adriano Spatola, Giulia Niccolai, Nanni Balestrini, Emilio Villa, Patrizia Vicinelli, Stelio Maria Martini, Luciano Caruso, Eugenio Miccini, Franco Vaccari, Anna Oberto, Martino Oberto OM, Corrado D’Ottavi, Ugo Carrega, Vincenzo Ferrari.

Alla tavola rotonda conclusiva, con il coordinamento di Corrado Maltese, avevano partecipato Gino Baratta, Francesco Bartoli, Germano Beringheli, Vittorio Fagonne, Martino Oberto OM; Edoardo Sanguineti.

Adesso ero pronta ad affrontare Fluxus… ma questo sarà l’argomento di una prossima risposta.

G.L.: Come mai alcuni movimenti importanti in quegli anni come ad esempio l’Arte Povera non sono stati inclusi nella ricognizione che ha raccontato nella risposta precedente?

C.G.: Come avevo detto all’inizio, in quegli anni c’erano tre gallerie molto affermate in città e una di quelle, la Bertesca aveva presentato la prima mostra di Arte Povera nel 1967, mostra curata da Germano Celant e dal direttore della galleria Francesco Masnata. Io provavo un grande interesse per questo movimento… ricordo che la vista di “Giovane che guarda Lorenzo Lotto” di Paolini nel 1968 mi aveva dato la sensazione di un ago gelato che mi perforasse il cervello e la mostra di Harald Szeeman “Quando le attitudini diventano forma” alla Kunsthalle di Berna nel 1969 mi aveva spinto ad aprire la galleria. Ma quello era allora terreno minato… impossibile da frequentare senza muovere le ire di Giove e di Marte!

CONTINUA…

English text

Interview with Caterina Gualco (part one)

#wordartist #interview #caterinagualco

Gabriele Landi: Hi Caterina, when were your first encounters with art?

Caterina Gualco: In the mists of time… I grew up in an enchanted garden, with an orchard, roses and iris plants… I remember a spring morning… the apple and pear trees like white clouds and the flowerbeds covered with thousands of little blue flowers. There, I think that was the first moment when I thought of beauty as a fairy godmother.

A little later – I was in fifth grade or sixth grade – at school I was given a mini-book on Amedeo Modigliani as a prize… I immediately fell in love with it and, looking at his elongated figures, I found myself comparing them with those of Simone Martini, whom I already knew. I think that was the first movement that pushed me to turn the object of my interest into the object of my work.

GL: What studies did you do and what, if any, important encounters did you have during your formative years?

CG: I came out of primary school with top marks and I would have loved to go to classical high school. But the choice was decided by my father… a school only for girls and close to home… And I ended up at the Liceo Linguistico Grazia Deledda in Genoa, which made me unhappy for a long time. But then I became passionate about modern languages (English, French and Spanish were studied as well as Latin) and in that same school I was lucky enough to meet the person who ‘opened my third eye’, as I like to say. It was indeed an extraordinary art history teacher, Maria Grazia Carbone Pighetti, who with her passionate lessons, seasoned with irony and a pinch of mischief, helped me to identify what would later be the greatest interest of my entire life in the field of study and work.

In any case, I owe a great deal to my mother, a very cultured and extremely sensitive woman, a teacher by vocation, who had already led me by the hand into the divine territory of art in my early years.

G.L.: Among the various possibilities that the art world offers, how did you come to the idea of opening a gallery?

C.G.: I did not go to university because my family of origin needed my contribution. I worked four years with languages, then I got married, very young. Some time later my mother became seriously ill and died… And I in turn was ill for a year, all psychosomatic…

Two years later my young husband went to England for work. He proposed that I go with him, it was May 1968, during the break between the two hot periods… I was 15 days alone in London… I saw everything that was possible to see. I walked thousands of miles

In this city that seemed to me a hundred years ahead of ours… the flower children, the miniskirts, the exhibitions….

It was on the return journey that I decided I couldn’t stay at home and be a good mother, a petit-bourgeois lady. I wanted to work and I wanted to work in the art world. I couldn’t teach, I didn’t have the necessary qualifications… and in the end I decided that the only option was to open a gallery.

I thought it would be easy… and it really wasn’t!

GL.: Do you narrate?

C.G.: Tell… a tale half a century long…

Let us start with the choice, or rather, the invention of the name, Unimedia, found when the various “mixta media” “multi media” etc. were not yet on the horizon. A paradoxical name that brings together a singular and a plural, in an attempt to synthesise “art as the first and most important means of mass communication”.

Then, of course, the search for space, in the historic centre, even there when the historic centre was fairly avoided for security reasons. But what interested me was dealing with the contemporary right in the heart of the old town. I had found the space, very charming, large and… very cold in winter, in Palazzo Barabino, a 17th-century building, not noble, but in any case with very high vaults and even an alcove, in which I had placed my office, provoking mischievous comments from the male visitors… I was young then, times were very different and I often had to defend myself!

One entered the space, which consisted of a salon that was a perfect cube, 6 metres by 6 metres with the vault also 6 metres above the floor, by climbing a steep and narrow slate staircase… the reason for other comments that were not always pleasant. Then there was the alcove, a storeroom and toilets. A small, delightful terrace overlooked vico dei Garibald, a side street of Via Luccoli, the ancient Roman Lucus. The first bad adventure had come during the work needed to make the space fit for purpose. Someone I trusted had proposed a small company to me… two days after starting work, I had discovered that it was a band of desperate people, with no skills and no… insurance… Some sort of scaffolding they had built to paint the ceiling had collapsed and one of the poor guys had broken his leg… Endless troubles that could have dampened any enthusiasm that wasn’t stainless steel!

G.L.: Once the space was open, how did you orientate the programming of the activity?

C.G.: To answer this question I have to talk about the situation of contemporary art in Genoa in the early 1970s. There was no museum, no public space to promote meetings, contemporary art was really managed by a few private individuals who had a good, very limited audience of attentive collectors. The galleries that counted in the city were very few, but very powerful. There was the historic Galleria Rotta, one opened in 1917 by Roberto Rotta, who had a contract with De Pisis, De Chirico and presented the established artists of the historical avant-gardes. There was Galleria La Polena, which was definitely involved with geometric abstract, both historical and contemporary. And there was the Bertesca, whose director Francesco Masnata had chosen the path of Conceptual and Arte Povera… All these so-called movements or groups were absolutely unapproachable on pain of… death.

I, totally clueless but not to the point of being unaware, had begun to move with baby steps… introducing artists to whom I sometimes arrived in an extravagant manner. The artist with whom I had opened the gallery was the Venetian Saverio Rampin, a pupil of Vedova, who had been recommended to me by what would later become a great friend, Mr Scheggi of the Tipografia Artigiani Grafici.

In the Genoese desert there was an enlightened critic who wrote reviews in the newspaper Il Lavoro, Germano Beringheli. He too had given me pointers on virtually unknown but very interesting young artists! To give an example, I would cite Beppe Dellepiane… His exhibition, in which we exhibited a bicycle covered in bronze, mounted on a platform with red cords around it, had created a scandal in the environment. The newspaper Il Secolo XIX had published a review by Sergio Paglieri who wondered whether the ‘young gallery owner from Vico dei Garibaldi’ (the gallery’s address) wasn’t fooling everyone.

G.L.: Were you really making fun of everyone? After these first episodes, how did you continue your activity?

C.G.: In reality I was moving in a sea of difficulties… After a year in the gallery, my then young husband, who at the beginning seemed enthusiastic about my work, gave me an ‘aut aut aut: the gallery or me… Very little money, very little, two small children… My father was against it… I would reasonably have had to give it all up! But whoever is born with a passion receives a great gift from the fairy godmother… but then there’s nothing to do… you can’t give up

I tried to find out as much as possible about what was going on in the art world with all the means available at the time, and they were very few. Still through Germano Beringheli I had discovered the Sardinian Transactional Group, which wandered between the conceptual and the recuperation of a certain figuration. One of its members, Ermanno Leinardi, had really caught my attention… His paintings, on canvas mounted on a frame in the most traditional way, presented moving ‘O’s’, black on a white field or white on a black field. It was a beautiful exhibition, presented by Beringheli and Corrado Maltese, who had just arrived in Genoa at the time as Art History professor at the University. This exhibition had aroused the ire of the usual well-wishers with consequent attacks in the newspapers. The fiercest was the Secolo XIX, conservative like most Genoese.

In the spring of 1972, I had laboriously managed to get myself to participate in the Genoa Art Fair. I had a stand that I thought was beautiful… with – among others – a work by Beppe Dellepiane, quite tragic and not very suitable for a Fair. It was a kind of sarcophagus with an engine turned off inside. The Fair Director had had the good idea of organising a treasure hunt and one of the stops was at my stand, right in Dellepiane’s work. I let you imagine the chaos that ensued!

In 1972, I presented an exhibition of Bice Lazzari, the great Italian abstract artist of the 1930s. The exhibition was extraordinary, very well received by the public and the critics. Among other things, it had also given me the opportunity to meet the great Carlo Scarpa, who was then working on the renovation of the Carlo Felice Theatre and was Bice’s brother-in-law. On the morning of the opening he had come to see the exhibition. I remember all this with great emotion… I have always loved Scarpa’s work very much, I have seen everything he built and renovated… I went twice to Altivole di Asolo to see his Brion Monument…

Little by little I gained confidence and broadened my horizon. In 1972 there was an exhibition of Czechoslovak artists, including the already well-known Jiri Kolar and Kolibal, who was to become one shortly afterwards. And in 1973 I organised the exhibition ‘Towards Whiteness’, curated by Paolo Fossati (whose book ‘L’immagine sospesa’ had introduced Italian abstractionism to the world). It was an exhibition with many artists, some young and still unknown and others already well established; to name but a few, Bonalumi, Calderara, Gastini, Griffa, Manzoni, Fontana.

And then, finally, the first truly historical exhibition ‘Abstractists in Como in the 1930s’. To organise it and find the works, I had gone to Como and with the help of Luciano Caramel, a great person and a great friend, I had met Radice and Galli, who are still living. Two little anecdotes: Radice was convinced that I was there to steal his works and Galli was courting me, singing the praises of the Duce!

G.L.: How did the exhibition on the abstract artists of the 1930s go and which other artists besides Radice and Galli were included by Caramel in the exhibition?

C.G.: “Abstractists in Como in the 1930s” Carla Badiali, Aldo Galli, Carla Prina, Mario Radice, Manlio Rho, Arch. Giuseppe Terragni. Catalogue with text by Luciano Caramel. From 24 January 1974

This was the announcement with which we announced the event. A catalogue had also been made, with text by Luciano Caramel. The exhibition was very beautiful and had been very well received! I remember that I had sold a beautiful drawing by Terragni concerning the Casa del Fascio in Como. In this regard I have two small anecdotes, very significant at the time and in the Genoese atmosphere. A few days after the inauguration, a gentleman had arrived at the gallery with a rather dim and insignificant appearance, all grey in his clothes, hair and face. He had lingered for a long time looking at the works and before leaving he had given me his business card, telling me that he wanted to buy Terragni’s drawing, to call him when the exhibition was over. Shortly afterwards, a really famous and important collector, to whom one of the leading galleries owed its fortune, came to the gallery. I told him about the visit, expressing my perplexity with him… He told me everything… How could I not know that the gentleman in grey was one of the greatest collectors of his time? Well, I didn’t know…

When the exhibition was over, I had phoned and gone to deliver the drawing. And another unbelievable story had greeted me… In that beautiful house, with extraordinary works on the walls, there was a secret room, in which works bought from galleries that were not the gallery of reference were hung. I confess that I would like to name all the names here, but the sense of discretion does not allow me to, even though all the protagonists are no longer with us. For “The Body as Language” Vito Acconci, Gunter Brus, Gilbert & George, Urs Luthi, Hermann Nitsch, Luigi Ontani, Gina Pane, Michele Zaza.

For “Psychic and Formal” Max Bill, Victor Vasarely, Richard Paul Lohse, Antonio Calderara, Bice Lazzari, Giorgio Griffa, Claudio Verna.

For “Structure and Measure” Marco Gastini, Stanislav Kolibal, Maur Reggiani, Riccardo Guarneri, Piero Manzoni, Mario Nigro, Sol LeWitt.

For “The Forced Gesture” Lucio Fontana, Albino Galvano, Osvaldo Licini, Emilio Scanavino.

For “La visione Fluttuante” Carlo Belloli, Arrigo Lora-Totino, Mirella Bentivoglio, Adriano Spatola, Giulia Niccolai, Nanni Balestrini, Emilio Villa, Patrizia Vicinelli, Stelio Maria Martini, Luciano Caruso, Eugenio Miccini, Franco Vaccari, Anna Oberto, Martino Oberto OM, Corrado D’Ottavi, Ugo Carrega, Vincenzo Ferrari.

The concluding round table, coordinated by Corrado Maltese, was attended by Gino Baratta, Francesco Bartoli, Germano Beringheli, Vittorio Fagonne, Martino Oberto OM; Edoardo Sanguineti.

Now I was ready to tackle Fluxus… but that will be the subject of a future answer.

G.L.: How come some movements that were important in those years, such as Arte Povera for example, were not included in the reconnaissance you mentioned in the previous answer?

C.G.: As I said at the beginning, in those years there were three very established galleries in the city and one of them, the Bertesca had presented the first Arte Povera exhibition in 1967, an exhibition curated by Germano Celant and the gallery director Francesco Masnata. I had a great interest in this movement… I remember that the sight of Paolini’s ‘Giovane che guarda Lorenzo Lotto’ (Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto) in 1968 had given me the feeling of a frozen needle piercing my brain, and Harald Szeeman’s exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” at the Bern Kunsthalle in 1969 had prompted me to open the gallery. But that was then minefield… impossible to attend without incurring the wrath of Jupiter and Mars!

TO BE CONTINUED…